1. Introduction

Recovering biomaterials, such as alginate-like exopolymers (ALEs), sulfated polysaccharides (SPs), tryptophan, and so on, from excess biomass generated in wastewater treatment processes has attracted great interest for research and applications [

1,

2]. Among them, ALEs, major constituents of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), recovered from microbial biomass have been considered as high value-added biomaterials with wide application potentials [

3]. For example, ALE was evaluated as a coating material and a bio-sorbent for the removal of refractory pollutants [

4]. Moreover, several researches have also reported that ALE shows promise for application in the food, paper, construction, immobilization of microorganisms, and agriculture industries for its biodegradability, non-toxicity, and similarity with commercial chemical polymers [

1,

3,

5,

6]. For this reason, market conditions are especially favorable for the production of ALEs from excess biomass. For example, a total of 85 kilotons of ALEs are expected annually to be retrieved from ten individual wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the Netherlands, and they are estimated to produce 170 million euros by 2030 [

7]. Under this circumstance, enhancing the ALE recovery from excess biomass and improving its properties is significant for promoting a paradigm shift of WWTPs from a waste stream to a resource recovery factory.

Several researches have shown that the ALE formation was significantly affected by operating conditions of wastewater treatment processes, including temperature, influent carbon source, sludge retention time (SRT), etc. [

8,

9,

10]. For example, Li et al. (2022) [

10] found that the yields of ALEs could be enhanced from approximately 130.0 mg/g VSS to 303.3 mg/g VSS with the decrease in temperature from 24 °C to 12 °C. Moreover, Ferreira dos Santos et al. (2022) [

9] demonstrated that using acetate as the influent substrate was favorable to enrich ALE formation in the aerobic granular sludge (AGS), where the ALE yield extracted from the AGS system with acetate as a carbon source was 2.3 times that extracted from the AGS system in the presence of propionate as substrate. Although the ALE production could be enhanced by adjusting the above-mentioned operational conditions, the implementation of relevant strategies is frequently not cost-effective and not feasible in practice [

11]. Therefore, effective and sustainable approaches need to be developed and evaluated for the recovery of highly valuable biopolymers from wastewater treatment processes. Moreover, it is reported that the granulation rate of AGS, as well as the composition of microbial communities within the granules, may be considerably influenced by the organic loading rate (OLR) [

12,

13]. For example, Yang et al. (2014) [

12] revealed that numerous strains such as

Pseudomonas,

Clostriduim,

Thauera, and

Arthrobacter could be enriched in the formed granules when the OLR increased from 4.4 to 17.4 kg COD/m

3/d, which functioned as the secretion of extracellular cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) and EPS production. Therefore, it is expected that the ALE formation might be influenced by feed OLR. However, the investigation of the influence of OLR on ALE recovery from municipal wastewater is still limited.

Regarding municipal wastewater, chemical oxygen demand (COD) levels in China’s municipal wastewater typically range from 200 to 400 mg/L, corresponding to an average low OLR in wastewater [

14]. Optimizing the operational condition of the wastewater treatment process, such as applying a low hydraulic retention time (HRT), could improve the OLR and provide an advantage in the screening of EPS-forming microbes. In addition, flocculent sludge (e.g., conventional activated sludge) and biofilm-based biological processes (e.g., the moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) and granular sludge) have been widely applied in municipal wastewater and industrial wastewater treatment [

15,

16,

17]. Among them, the MBBR process has been identified as a popular biological treatment process due to its high microbial activity, excellent environmental adaptability, and great capacity to endure high organic loading [

18]. Therefore, it is expected to improve the biopolymer recovery potential from excess biomass of the MBBR process through optimizing HRT and OLR conditions. However, the optimal operational condition, including the recovery potential, purity of ALEs, and the underlying mechanism of this optimal strategy, is still limited.

For the reason described above, this study was initiated to examine the impact of HRT and OLR on the ALE recovery potential from municipal wastewater through a biofilm-based process. The treatment performance, ALE recovery potential, and properties analyses were assessed. Moreover, an additional assessment of the microbial community composition was further conducted to reveal the underlying mechanism of ALE formation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Setup

A cylindrical MBBR with an effective volume of 2.0 L was used in this study. The system was configured to facilitate aerobic conditions, and the process of fluidization of the bio-carriers was ensured by incorporating a microporous aeration disk and a mechanical stirrer with a speed of 200 rpm into the system. The aeration was supplied with a flow rate of 1 L/min by the air diffusers located at the bottom of the reactor. The influent was introduced through a peristaltic pump from the bottom of the reactor, while the effluent was discharged through the overflow weir positioned at the top of the reactor. The high-density polyethylene K1 carriers were used in this study, whose volumetric filling ratio (carrier volume to effective volume ratio) was 25%, specific surface area was 760 m2/m3, and diameter, as well as height, were both 1 cm. During the system start-up phase, the seeding sludge (VSS/TSS = 0.7) taken from an aerobic tank in a municipal WWTP in Qingdao, China, was utilized with an inoculation concentration of 100 mg TSS/L.

2.2. Wastewater Characteristics and Operational Conditions

As illustrated in

Table 1, the composition of synthetic municipal wastewater and the operational conditions of the MBBR have been thoroughly delineated. The concentrations of COD, NH

4+-N, and phosphorus were set to 500.0, 25.0, and 5.0 mg/L, respectively. The CH

3COONa, NH

4Cl, and KH

2PO

4 were used as the carbon source, nitrogen source, and phosphorus source, respectively. A trace element solution was also used according to Zhang et al. (2022) [

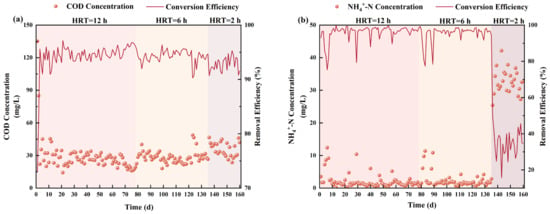

18]. During the entire experiment, the MBBR was consistently maintained at various HRTs of 12.0 h, 6.0 h, and 2.0 h, respectively, which corresponded to organic loading rates (OLR) of 1.0 kg Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)/m

3/d, 2.0 kg COD/m

3/d, and 6.0 kg COD/m

3/d, respectively. The concentration of dissolved oxygen (DO) was maintained within the range of 5.0–6.0 mg/L. The temperature was controlled between 22.0 and 25.0 °C, and the pH was kept within the 7.0–8.0 range.

2.3. Analytical Methods

General parameters, such as COD, NH

4+-N, NO

3−-N, NO

2−-N, total nitrogen (TN), mixed liquid suspended solids (MLSS), mixed liquid volatile suspended solids (MLVSS), and sludge volume index (SVI

30), were measured in accordance with the APHA standard methods [

19]. The ALE was extracted by the process of modified high temperature-sodium carbonate, and the detailed method was described in Zhang et al. (2024) [

1]. The concentrations of proteins (PN) and polysaccharides (PS) were analyzed through the utilization of the modified Lowry–Folin method [

20] and the phenol–sulfuric acid method [

21], respectively. An alginate equivalent analysis was performed to evaluate the purity of the ALE sample through the phenol–sulfuric acid method, and the commercial alginate was utilized as standard [

22]. In order to further investigate the organic proportions of the ALE, the total organic carbon (TOC) was determined by analyzing it using a TOC analyzer (Analytica Jena AG, Jena, Germany). The characterization of the surface chemical functional groups of the ALE samples was accomplished by means of Fourier-transformation infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA., USA). First, 2 mg dried samples and 98 mg KBr were measured at the wave number range of 4000–400 cm

−1. UV-visible absorbance measurements (DR5000, HACH, Loveland, CO, USA) were also carried out to detect the humification and aromaticity of the ALE from 800 nm to 200 nm. All measurements were carried out in triplicate, and the experimental results were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

At steady state, the collection of biofilm and suspended biomass samples was undertaken for the purposes of DNA extraction, with these samples then being subjected to a mixed liquid process within the MBBR. The Power Soil DNA extraction kit (OMEAG-soil, Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) was utilized for the extraction of DNA from the samples. The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The amplicon sequencing was conducted on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Majorbio, Shanghai, China) and then quality-filtered and merged by fastp (v 0.19.6) and FLASH (v 1.2.7), respectively.