3.2.2. Analysis of the Variables of the Message and Its Emotional Content

Campaign actions, rallies, and appeals to vote are the most represented topic in the videos viewed by most of the leaders, such as those of Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Slovenia, Italy, Poland, Portugal, and Romania, as well as for Marine Le Pen (RN), Kyriakos Velopoulos (EL/EΛ), Afroditi Latinopoulou (Foni Logikis), and László Toroczkai (Mi Hazánk). There are also other relevant issues for some politicians, such as security and immigration for the representatives of AfD (Germany), VB (Belgium), and CHEGA (Portugal); criticism of the political system or European institutions for the leaders of EL/EΛ (Greece), Mi Hazánk (Hungary), and Svoboda a přímá demokracie (Czech Republic); the appeal to traditional values for the leader of the Greek NIKI party; the narrative of crisis or decline for Slawomir Mentzen from Poland; and the rejection of progressive social movements for Morten Messerschmidt, candidate of Dansk Folkeparti. Other issues of varying content were included in the category of other issues, which are of interest to the leaders of Vox (Spain), Republika (Slovakia), Reconquête (France), Foni Logikis (Greece), KDNP (Hungary), and Fratelli d’Italia and Lega Salvini Premier (Italy).

In general, the vast majority of TikTok publications by the political leaders analysed are targeted towards a diverse audience, with only 25 out of 472 videos examined targeting youth. Videos aimed at young voters tend to focus on topics related to campaign actions and calls for votes (10 videos), promises for youth (5 videos), security and immigration (3 videos), traditional values (3 videos), and narratives of crisis or decline (2 videos). These topics are essential to the speech of the extreme right. Moreover, efforts are made to mobilise young people through calls for votes and specific youth pledges. These findings suggest that far-right parties seek to strengthen their support base among young people through issues that reinforce a sense of national identity, security, and rejection of globalisation, while to a lesser extent, they also attempt to connect with their expectations through direct promises.

Some political leaders who are targeting young audiences are Alice Weidel (Germany), Tom Van Grieken (Belgium), Santiago Abascal (Spain), Marine Le Pen (France), Dimitris Natsios (Greece), Viktor Orbán (Hungary), Matteo Salvini (Italy), André Ventura (Portugal), Tomio Okamura (Czech Republic), and George Simion (Romania). In the case of the AfD leader, the theme of connecting with this audience focuses on political campaign actions and appeals to vote (2 videos), as does the leader of the AUR (1 video). This theme is also used by the leader of VB (1 video), alongside issues of national security and immigration (2 videos), criticism of the political system and other formations (1 video), and election promises to the youth (1 video). The leader of VOX, in addition to releasing a video on appealing to the youth vote, also published a video on another topic, a scenario akin to that of CHEGA. The videos include a video on campaign actions and rallies and another on immigration. The SPD leader, in addition to urging young people to vote in a video, also exposes the decline of the country to them in a video and makes specific promises in another video. These proposals or commitments to the young public are also recurrent topics for the leaders of Rassemblement National (1 video) and Viktor Orbán (1 video). Lastly, the leaders of Lega Salvini Premier and Niki dedicate a video each to connecting with young people through traditional values.

An analysis of the prevailing emotions reveals a strategic plan based on the balanced use of positive and negative emotions to mobilise the electorate. The most prevalent emotion was pride and ambition (80 videos, 16.95%), a positive emotion that aims to reinforce national identity and the perception of personal and collective accomplishment, focusing on the voter’s self-worth and their part in shaping political change. However, emotions of intense negative emotion (74 videos, 15.68%) and those of danger and insecurity (73 videos, 15.47%) also stand out as key pillars of emotional communication. This shows a strategy that appeals to fear, the urgency and perceived threat of factors such as immigration, globalisation, or cultural decline, negative emotions that could be explained in the context of a continent affected by a high level of irregular immigration, receiving thousands of illegal immigrants every year, especially from Southern and Eastern European nations, as well as thousands of asylum seekers. This situation is being exploited by a large part of the extreme right-wing parties to demand protection for their countries and strict border control from the European Union, as they see immigrants as responsible for a large part of the continent’s problems (insecurity, social conflict, criminality, loss of cultural identity, etc.).

On the other hand, emotions of hope and illusion (68 videos, 14.41%) and empathy and social connection (65 videos, 13.77%) complement this framework, providing a balance for emotional contrast and motivating the audience with visions of a better future under their leadership. Despite the relative weight of emotions such as personal enjoyment (57 videos, 12.08%) and displeasure (55 videos, 11.65%), their presence reinforces the narrative of enjoyment under traditional values and rejection towards political actors or institutions considered adversaries. This emotional design shows a sophisticated use of TikTok to capture the public’s attention, creating a balance between fear and optimism. In videos that are specifically targeted towards young individuals (24 videos), these emotions are amplified to mobilise this crucial audience towards the polls.

The majority of the videos analysed exhibit negative emotions. These include “Emotions of danger and insecurity” (73 videos), “Emotions of displeasure” (49 videos), and “Intense negative emotions” (74 videos). These emotions are predominantly associated with negative polarisation (208 videos) and strategic orientations focused on danger and insecurity (107 videos) or anger and suffering (93 videos). In many of these videos, the possible dangers of immigration and the dissatisfaction with the political practices of the European Union and, above all, of the representatives and political leaders of the respective nations, are central themes with negative connotations. This approach reflects a communication strategy that appeals to fear, mistrust, and indignation, typical elements in extreme right-wing speeches, which aim to mobilise the audience by highlighting threats such as immigration, globalisation, or progressive movements.

Nevertheless, there exists a deliberate utilisation of positive emotions, such as “Hope and Illusion” (51 videos) and “Pride and Ambition” (80 videos), which are associated with positive polarisation (214 videos) and strategic orientations focused on social connection and hope (119 videos) or personal well-being (88 videos). These emotions provide an optimistic message, presenting leaders as a solution to the problems. This approach helps build a “rebirth” or “new opportunity” narrative that is especially attractive to young voters.

Although neutral strategic orientations are less common, they do have a specific role. Emotions such as “pride and ambition” and “positive emotions of personal enjoyment” are occasionally associated with neutral positive or negative trends (28 videos), suggesting a tactical approach to connecting with indecisive audiences or moderate emotional polarisation. Emotions of empathy and social connection are mostly linked to positivity and a focus on hope, which humanises the political message and strengthens the emotional bond with the public.

The distributions reflect a dual strategy of mobilisation through negative emotions (crisis, fear) and an optimistic and hopeful message based on positive emotions (pride, illusion). This balanced narrative allows for the engagement of more radicalised supporters while attracting undecided or moderate voters. This approach confirms the use of emotionally sophisticated and characteristic communication techniques in electoral contexts.

Emotional tactics differ across nations and political leaders. The communicative strategies of the far-right formations have identifying nuances in each of them, sharing, however, some features and factors in terms of the issues addressed, as we have seen, and the impressions conveyed. For example, the negative emotions of displeasure and those linked to danger and insecurity correspond in many cases to current events, acts, or speeches in which leaders express their misgivings and concerns about what they see as a social and cultural drift of their nations and of Europe itself, mainly due to the effects of the migration crisis. The risks that uncontrolled immigration has and may have for citizens and national customs are the focus of many of the messages we have seen, with allusions to problems of coexistence, crime, rape, and terrorism and radicalisation, in the case of Islamism. As irregular immigration is a problem that especially affects Southern and Eastern European nations, this emotion of danger is more prevalent in the discourses of far-right leaders in these regions, as can be seen in the cases of the Czech Republic, Portugal, Slovakia, and Spain, but also in other nations with a high foreign population (Belgium and Germany). Negative emotions and dislike, in addition to the previous immigration theme, is also linked to apathy and criticism of both the political system (other parties, opposition, etc.) and European institutions. This only goes to show the dissatisfaction of European far-right leaders with the political context of their nations and the continent.

Emotions of danger and insecurity are prevalent across the board in the videos of the two AfD leaders, present in more than half of the cases (6). This emotion is also strongest in the videos of candidates Milan Uhrk, André Ventura, and Santiago Abascal (8 videos each), although in the case of the Slovak leader, positive emotions of personal enjoyment and others of displeasure also stand out (6 videos each). In the case of the two Iberian leaders, the positive emotions of personal enjoyment (7 videos in CHEGA) and empathy and social connection (4 videos in VOX) are also noteworthy. However, in the videos of the Austrian leader, the Greek Natsios, and the Slovenian Jana, the emotions related to hope and illusion shine more brightly (4 videos, 4 videos, and 1 video, respectively), as is the case with Tom Van Grieken, where these emotions, together with those of danger and insecurity, tie in number (16 videos each) and represent more than half of the VB sample.

The emotions of empathy and social connection are the most important for leaders Kostadinov (3 videos) and Sosoaca (5 videos), being also relevant for Orbán (10 videos), together with the emotions of hope and illusion and pride and ambition (4 videos each). It is precisely this emotion of pride that appears most frequently in the leaders of Mi Hazánk (9 videos), Fratelli d’Italia (7 videos), Lega Salvini Premier (16 videos), and Konfederacja (1 video), although it is not in the majority. Therefore, it is possible to discern pronounced negative emotions in the cases of Salvini (16 videos), Toroczkai (5 videos), and Mentzen (1 video), as well as positive emotions of personal enjoyment in the five videos of Meloni.

These negative emotions can also be observed in the leaders Okamura (23 videos) and Simion (12 videos), as well as others of danger and insecurity (11 videos) in the Czech politician and pride and ambition (11 videos) in the Romanian politician. Lastly, we would like to highlight other predominant emotions that were observed in the remaining candidates. After analysing the accounts of the leaders of Denmark and France, we observe a preference for positive emotions and personal enjoyment (1 video for Messerschmidt, 9 for Le Pen, and 6 for Zemmour), as well as for the Greek leader Latinopoulou (2 videos). In the context of the EL/EΛ formation, it is noteworthy that 14 videos exhibit emotions of displeasure, in contrast to 11 videos where empathy and social connection prevail.

The Chi-square test conducted between the variables ‘polarisation’ and ‘intensity’ yields a Chi-square value of 63.63, with a minimal p-value (p < 0.001), indicating a significant correlation between the two variables. The expected frequencies reflect significant differences in the observed distribution of the data. In particular, messages of low intensity are predominantly associated with negative (57 observed versus 35.82 expected) and neutral (16 observed versus 8.37 expected) polarisation. However, messages of high intensity are more present in messages with positive polarisation (86 observed versus 63.02 expected), while messages of average intensity show a more balanced distribution, with significant differences between the polarisation types.

This result indicates that the intensity of the messages is not agnostic to their polarisation. Positive messages tend to be more intense, possibly to inspire optimism and mobilisation, while negative or neutral messages tend to be less intense. This is likely a strategy to reduce the emotional impact and avoid emotional overload in the recipient. This suggests a strategic design for message intensity based on emotional and political orientation.

3.2.4. Analysis of Engagement and Response Variables

The distribution and range of “likes” goes from 2 to 522,100. Videos with more than 100,000 “likes” represent extreme cases; in the comments, the range varies between 1 and 27,100, showing a high concentration at low levels with some outliers; and in shared/favourites, the distribution ranges from 0 to 74,500.

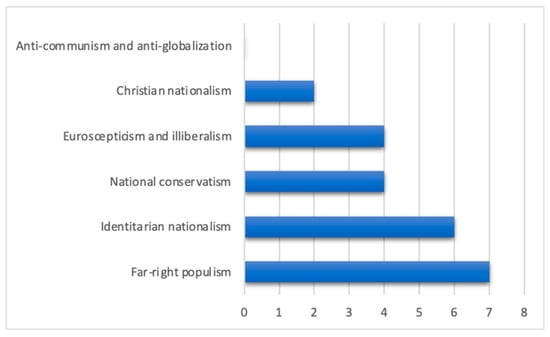

This indicates that videos related to the rejection of progressive social movements, the appeal to traditional values, cultural and national identity, and campaign actions and rallies generate the most interaction. This is followed by general themes (others) and those pertaining to security and immigration, or criticism of the political system and other parties. On the contrary, the less popular topics are those associated with Euroscepticism and anti-globalisation, promises for youth, crisis narratives, and rejection of progressive social movements, which may reflect a lower perceived emotional resonance or relevance in these areas.

It is observed that positive emotions of personal enjoyment generate the greatest normalised engagement, closely followed by those related to suffering and vulnerability and hope and excitement. These emotions, which mobilise both personal and collective aspects, appear to have a high impact on the interaction, adjusted to the popularity of the leader. Emotions such as danger and insecurity and unpleasantness also achieve a certain level of resonance, although to a lesser extent. Conversely, intense negative emotions and ambiguous categories such as other emotions generate significantly lower levels of engagement. These results, along with the calculated Engagement Rate (%) of 17.78%, underscore the importance of emotional content in driving engagement on TikTok. This pattern suggests that despite positive emotions leading to a close interaction, certain negative narratives manage to capture attention, possibly due to their emotional intensity.

Source link

Manuel J. Cartes-Barroso www.mdpi.com