1. Introduction

The Positive Youth Development (PYD) model proposed a strength-based perspective of the transition to adulthood, in which positive outcomes appear when the youth’s personal skills and contextual developmental assets are properly aligned [1,2]. The 5Cs model of PYD was presented by Lerner et al. [3], in which five thriving indicators are differentiated and expected to be related to better health and well-being in adolescent and youth samples [4,5,6,7]. These 5Cs are defined as follows: confidence (overall positive self-worth), competence (positive self-efficacy in life domains such as academic or social), connection (positive interpersonal relationships), character (adequate internalization of the social rules and values), and caring (feeling sympathy and empathy toward others). Evidence to date has determined that the 5Cs showed cross-lagged prospective associations with some positive outcomes across the youth period. Each C of PYD describes a developmental regulation, that is, an intersection between youth and their contexts. However, some paradoxical results have been observed concerning the dimension of caring in PYD (as a thriving indicator) and some mental health results. In a longitudinal study with adolescents in the US, Geldhof et al. [8] pointed out a small positive correlation between caring and depressive symptomatology. Along this same line, Dvorsky et al. [9] reached the same conclusion with a sample of US undergraduates. They also observed positive associations between caring, depression, and emotional regulation difficulties. Following Geldhof et al. [8], “Caring indicates developmentally and contextually appropriate levels of concern for others, and connection requires that the individual be embedded in, and supported by, a reliable and diverse social network” (p. 3). These authors supported the notion that excessive caring may be maladaptive because it produces a martyring developmental regulation characterized by overconcern about others’ thoughts and feelings.

In line with these results in US samples, several studies have also confirmed these paradoxical findings in European samples. Thus, Holsen et al. [10] found, in Norwegian youth, that caring was positively related to both anxiety and depressive symptoms. In Croatia, Novak et al. [11] found a protective role of PYD against adolescent mental distress, except for caring, which was related to more depression, anxiety, and stress. In this same line, Marin-Gutierrez et al. [12] demonstrated that caring was positively correlated with perceived stress, while Confidence and Connection played a protective role in Chilean adolescents. In Slovenia, Pivec and Kozina [13] have reported that caring was positively associated with anxiety and COVID-19 anxiety in a sample of adolescents. Some cross-national studies have also addressed this gap in the literature. Kozina et al. [14] analyzed youth samples from Slovenia, Portugal, and Spain, and showed that Connection and Confidence were protective factors against anxiety, while caring presented a detrimental effect. In a study with samples from Spain and Croatia, Gomez-Baya et al. [15] explored the associations between the 5Cs of PYD and depression with data collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. These authors concluded that more Confidence and more Connection were associated with less depressive symptoms, but more caring was associated with more depressive symptoms. Finally, a study with undergraduates from Peru and Spain during the pandemic, conducted by Manrique-Millones et al. [16], showed negative effects by Competence, Confidence, Character, and Connection on depressive symptoms, while Caring had a positive one in both samples. Other studies have reported the association between dispositional compassion and suicidal ideation [17] and depressive symptoms in adolescent and youth samples [18].

Based on these findings about the maladaptive consequences of caring, some authors have tried to provide some possible explanations. Geldhof et al. [19] argued about the importance of the interactions among the 5Cs of PYD. More than two decades ago, Schieman and Turner [20] found that the association between empathy and distress was stronger among people who reported less education, lower self-esteem, and lower mastery. Thus, they posited that one component can sometimes be related to psychological maladjustment depending on the quality of the interactions between youth and their contexts. Those youths who spend elevated and exhausting attention to others’ thoughts and feelings may have increased difficulties developing positive psychological adjustment. This kind of over-investment in others’ lives may lead to empathic stress when the boundaries between other people and themselves get blurred, and they cannot cope with that situation. Thus, high scores in the caring component of PYD may produce some exaggerated emotional hypersensitivity, instead of a way to provide useful prosocial and altruistic behavior. Adaptive help to others has been associated with positive mental health consequences [21].

Furthermore, some authors have pointed out the differential impact on mental health by empathy for positive or negative emotions. The concept of empathy has been used to refer to different phenomena associated with emotion sharing, including caring for others, understanding others, and validating others’ emotions, as underlined by Wondra and Ellsworth [22]. These authors concluded that the main issue in the study of emotions for others is what makes something that is happening to another person good or bad to the empathic observer. Thus, empathetic response is subject to other stimuli, and a range of different emotions may evoke empathy, distinguishing between negative empathy (i.e., empathy for others’ pain or sadness) and positive empathy (i.e., empathy for others’ happiness) [23]. Andreychik and Migliaccio [24] concluded that empathizing with the positive or negative emotions of others implied different patterns of social behavior and social emotion. In another study, Andreychik and Lewis [25] distinguished between positive and negative empathy, examining the motivation to help others. They found that negative empathy is related to a motivation to help others avoid negative emotions, contrary to positive empathy, which is associated with an other-oriented motivation to help others approach positive emotions. Furthermore, Morelli et al. [26] reviewed the emerging study of positive empathy. They concluded that positive empathy has been associated with more prosocial behavior (i.e., spending on others, emotional support, and tangible assistance), well-being (i.e., positive affect and life satisfaction), and more social connection (i.e., closeness, trust, and relationship satisfaction). Concerning the association with emotional problems, these authors argued that more evidence is still needed to more clearly understand how altered sensitivity to others’ positive emotions may contribute to clinical problems. Morrison et al. [27] concluded that individuals with social anxiety, compared to healthy controls, were less able to vicariously share others’ positive emotions. With regard to the link between positive empathy and prosocial behavior, Telle and Pfister [28] presented a model in which the perception of positive affect in others triggers vicarious positive emotion (positive empathy), which is associated with mood maintenance motive, which also triggers prosocial behavior, and in turn it, causes genuine positive emotion.

If the paradoxical effects of caring and empathy have generated some interest in the scientific community, the examination of gender differences seems to be a key aspect to guide the design of effective interventions to protect youth mental health. Some studies have found some gender differences in caring, with women showing higher mean scores than men [29,30]. Conway et al. [31] found, in Ireland, higher scores in caring among female adolescents, and Gomez-Baya et al. [32] found the same result in a sample of Spanish students from high school and university. Cross-cultural evidence has been documented concerning gender differences in caring morality, so women showed more interpersonal sensitivity in Korea, China, Thailand, and the USA [33]. Other studies have examined this tendency in gender differences along with its impact on related variables. In a 6-wave prospective study in the Netherlands, adolescent girls experienced an increase in prosocial behavior, which was predicted by higher scores in perspective-taking and empathic concern [34]. Moreover, in US undergraduates, women were found to report more empathy as well as more emotional reactivity than men [35]. Rochat [36] indicated that sex and gender differences in the development of empathy throughout the lifespan are due to the joint interaction of social and neurobiological factors, including early socialization, the brain’s structural/functional variances, and genetics and hormonal factors. Furthermore, the literature to date has documented well the emergence of gender differences in emotional problems since adolescence [37]. Gomez-Baya et al. [38] have shown that gender differences in anxiety may be partly due to the lower scores in positive identity and higher scores in positive values in women. Some psychosocial mediators have been proposed to explain gender differences in depression and anxiety across the life span [39], such as mastery, behavioral inhibition, rumination, and perceived interpersonal problems. In this line, stressful life events and emotional reactivity to these life events may explain gender differences in adolescents’ depression [40].

Given the mixed results regarding the caring dimension in PYD and the consistent gender differences observed, further research is needed to deepen our understanding of empathy’s role in psychological well-being [19,41]. More research is needed to jointly examine caring (which includes empathy for others’ suffering), and positive empathy (i.e., sharing others’ positive emotions), and their differential effects by gender on different indicators of youth psychological adjustment (e.g., depressive and anxious symptoms). Moreover, because of the consistent gender differences in emotional problems reported by the literature, further study is needed to understand to what extent those gender differences in depression or anxiety may be partly due to gender differences in the responses to others’ feelings. In addition to addressing a gap in the literature to understand the paradoxical effect of the caring dimension on youth psychological adjustment, this research may provide some insights for design intervention. Research evidence is needed to guide gender-based interventions to promote adaptive empathic skills in young people, aiming at enabling them to contribute to both their own and others’ well-being. Thus, the present study aimed (a) to examine the gender differences in caring, positive empathy, depression, and anxiety in Spanish emerging adults; (b) to analyze the associations between caring and positive empathy with mental health outcomes; and (c) to explore the mediational role of caring and positive empathy in the gender differences in both depression and anxiety.

4. Discussion

The present study had three aims. The first aim was to analyze the gender differences in caring, positive empathy, depression, and anxiety in Spanish emerging adults. The results indicated that women presented more positive empathy, more caring, and more depressive and anxiety symptoms. These results are consistent with previous literature on gender differences in caring [31], empathy [36], and emotional distress [39]. The second aim was to calculate the associations between caring and positive empathy with depression and anxiety. The results indicated that more caring was related to more depression and anxiety in women, while more positive empathy was related to less anxiety in men. The relationship of caring with anxiety and depression in women is consistent with the works by Pivec and Kozina [13] and Manrique-Millones et al. [16], which highlighted the detrimental effects of the caring dimension of PYD on mental health. The protective role of positive empathy is in line with the conclusions by Andreychik and Lewis [25] and Morelli et al. [26], which showed the associations between positive empathy and better mental health and psychosocial adjustment.

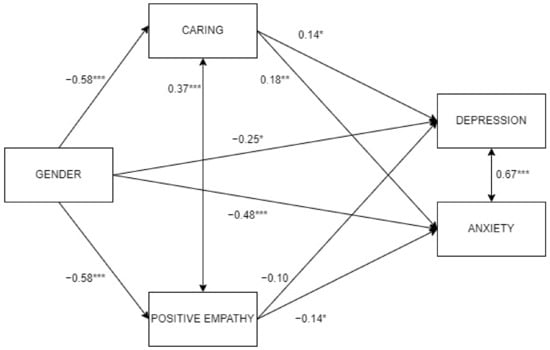

Finally, the third aim was to explore the mediational role of caring and positive empathy in the gender differences in both depression and anxiety. The results pointed out that (a) caring mediated gender differences in both depression and anxiety, while positive empathy mediated the gender differences in anxiety; (b) higher caring was related to more depression and anxiety, while higher positive empathy was related to less anxiety. Women reported more depression and anxiety partly due to their higher scores in caring. Despite the fact that women had higher positive empathy than men, this mediator was only protective against anxiety in the men subsample. These results can be explained by the gendered socialization in which women are taught to be more expressive and sensitive, displaying more caring toward others [49], together with lower self-confidence, more ruminative responses to negative affect, and a lower perception of their emotional skills [38,50,51]. These gender differences in the strategies for managing negative emotions may explain why experiencing the suffering of others can increase symptoms, especially among women [52]. Empathy can be protective for mental health in youth, as Rieffe and De Rooji indicated [53], but may increase emotional vulnerability when youth do not possess adequate emotional regulation skills [54]. Increased emotional reactivity in stressful life events may lead women to suffer more emotional problems when they do not possess adaptive coping styles [40]. These possible emotional regulation mediators of the detrimental effects of caring should be addressed in future research. These gender differences in the responses to negative affect may be consistent with Response Styles Theory by Nolen-Hoeksema [55], which underlines a more frequent use of rumination in females, what exacerbates the experience of negative affect. In the case of empathy for others’ positive emotions, positive empathy had been associated with positive upward spirals characterized by more prosocial behavior, well-being, and greater social connection. Thus, higher reactivity to others’ negative emotions in women may reduce the positive consequences derived from their higher level of positive empathy [56]. Following the Broaden-and-Build theory by Fredrickson [57], positive emotions broaden an individual’s momentary thought–action repertoire and build personal resources for coping, such as novel and creative actions, ideas, and social bonds. The higher protective role of positive empathy in men may be due to the use of more adaptive strategies to regulate positive emotions, which may increase the savoring of positive emotions and, in turn, foster life satisfaction and self-esteem [58], as well as decrease emotional symptoms [50].

Some limitations should be acknowledged in these results. First, the cross-sectional study design limits the analysis to associations between variables, preventing any inference of causation. A longitudinal design is necessary to investigate the directionality of the relationships between empathy and mental health outcomes. Second, the use of self-report instruments introduces subjectivity, which may be affected by social desirability bias, which may influence the results by a potential overestimation of dispositions and an underestimation of emotional problems. Future research could provide evidence using objective measures and clinical diagnoses. Third, some variables should be controlled or included in the model to explain depression and anxiety. For example, emotion regulation strategies, neuroticism personality traits, resilience skills, or perceived social support may have an important role in the empathy effect on stress generation. Fourth, a more comprehensive examination of empathy is recommended, separating cognitive and affective components [59], and other elements, such as interpersonal reactivity, perspective-taking, or empathic concern [60]. Fifth, future works should assess a representative sample of Spanish youth to generalize the conclusions. The present work assessed a convenient sample from 10 universities in Southern Spain. Sixth, the lack of gender equity in sample composition is an important limitation in the present study. Future research about gender differences in mental health should examine a gender-balanced sample [61].

Some implications for practice may be derived from the results of the present study. Interventions to increase empathy in men in order to foster further contribution to others may also be necessary. PYD interventions should aim at promoting equal opportunities for males and females to develop in a healthy way [62]. The integration of PYD and empathy education programs may be recommended to jointly develop caring skills and well-being. Thus, empathy competency should be central in higher education curriculums [63], to train the social and emotional skills needed for healthy professional development with evidence-based interventions. With undergraduate samples, some empathy education interventions were found effective in increasing empathy competency among medical students [64] and nursing students [65,66]. With an adolescent sample, a school-based social and emotional learning (SEL) program was found to be effective in activating social empathy in Ireland [67]. The practice of social and emotional skills, such as identifying emotions, perspective-taking, problem-solving, teamwork, and goal setting, allows for building positive associations between empathy and PYD. From this SEL framework, Cullen et al. [68] argued the importance of faculty members’ instruction in providing these skills to their students, especially during the transition from high school to university. Also, counseling/well-being offices at universities may implement group sessions or workshops to work with the students [69]. The results of the present study underline the need to improve empathy skills to protect psychological adjustment in male and female youth, by developing skills that enable them to care for others without experiencing symptoms and by developing skills to share and enjoy the positive emotions of others. The program Activate Empathy for Undergraduate College Students [70] was designed to teach empathy to students aged 18–25 with a 12 h module (including topics such as the definition of empathy, conflict resolution, the psychology of empathy, listening skills, and mindfulness exercises) using Kolb’s model of experiential learning (i.e., including opportunities for abstract conceptualization, active experimentation, concrete experience, and reflective observation) [71]. This program underlined that the most effective components of this empathy education program were the ability to perceive typical emotions in a situation, the ability to respond appropriately to someone else’s emotions, the ability to understand emotions in an interaction, and the ability to separate one’s emotions from another’s emotions. Thus, this intervention showed an integration between empathy and emotional regulation skills to prevent distress in caring situations.

Source link

Diego Gomez-Baya www.mdpi.com