1. Introduction

Tartary buckwheat (

Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.), a member of the

Fagopyrum genus in the

Polygonaceae family, is a pseudocereal. It most probably originated from southwest China and is widely cultivated in Asia, Europe, and North America [

1,

2,

3]. Tartary buckwheat grain is not only rich in starch, proteins with a balanced composition of essential amino acids (methionine, tryptophan, lysine, histidine), lipids, and minerals, but also contains abundant secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, and triterpenoids [

1,

4]. A large number of studies have suggested that Tartary buckwheat grain confers various health benefits to humans, including anti-oxidants, anti-inflammatories, anti-diabetic, anti-obesity, anti-hypertensives, and anti-carcinogenic effects, due to its high content of nutrients and bioactive secondary metabolites [

4,

5,

6]. As a result, Tartary buckwheat is considered a promising smart food crop for the future, and its grains have been used to develop TB powder, TB capsule, TB alcohol, TB noodle, TB tea, TB vinegar, and TB bread [

1,

6].

Genetic resources are the foundation of breeding progress. However, Tartary buckwheat breeding has progressed slowly over the past two decades, mainly due to the limited genetic diversity information available, which has greatly restricted the genetic improvement of the crop. Therefore, research on the genetic diversity of Tartary buckwheat, especially in large-scale germplasm collections, is urgently needed.

Morphological, cytological, and molecular marker technologies are the major methods for studying genetic diversity [

7]. Generally, morphological analysis can reveal genetic variation in genetic resources to a certain extent, but it is easily affected by environmental factors. Cytological analysis is time-consuming and labor-intensive. In contrast, molecular marker technology is simpler, and the results are more stable. Over the past several decades, many DNA-based molecular markers, including random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [

8], insertion/deletion (InDel) [

9], simple sequence repeat (SSR) [

10], and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) [

11], have been used for genetic analysis in many plants [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Among these markers, SSRs are more consistent than RAPD, more polymorphic than ISSRs, and easier to genotype than SNPs, making them widely used for genetic diversity analysis in plants [

16,

17,

18].

To date, several studies have explored the genetic diversity of Tartary buckwheat based on SSR markers. Sabreena et al. used seven ISSR and seven SSR markers to investigate the diversity of 35 Tartary buckwheat genotypes, demonstrating that both marker techniques are highly effective for genetic diversity assessment in Tartary buckwheat [

19]. Song et al. carried out a genetic diversity analysis of 112 Tartary buckwheat accessions from 29 populations using 10 SSR markers, revealing a high level of genetic diversity and significant genetic structure differentiation among the accessions [

2]. Kishore et al. found that 71 Tartary buckwheat populations exhibited a broad genetic base using seven SSR markers [

20]. More recently, Pipan et al. [

21] and Balážová et al. [

1] also used 24 and 21 SSR markers, respectively, to explore the genetic diversity of Tartary buckwheat, concluding that SSR marker technology is a reliable and stable technique for genetic diversity analysis and high genetic diversity exists in the Tartary buckwheat germplasms. Although these studies have provided insights into the genetic diversity of Tartary buckwheat germplasms, they have been limited by the small number of germplasm samples. More importantly, there is no or less investigation into the genetic diversity among wild, landrace, and improved Tartary buckwheat accessions in these studies.

In the present study, we analyzed the genetic diversity and population structure of 659 Tartary buckwheat accessions, including 101 wild, 383 landrace, and 175 improved accessions (breeding line and varieties), using 15 SSR markers. The research aimed to assess population variability and construct a core germplasm collection of Tartary buckwheat across different ecological conditions. The results not only provide valuable information for the selection and breeding of Tartary buckwheat germplasm resources but also offer a foundation for fully exploring and utilizing the excellent Tartary buckwheat genetic resources and formulating new hybrid combinations in the future.

3. Discussion

Understanding the genetic relationship among a large-scale collection of Tartary buckwheat accessions is crucial for the germplasm innovation and breeding of new cultivars [

22,

23]. Molecular markers have been widely used to investigate genetic variations at the DNA level [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

24]. Among all molecular markers, SSR markers are the most frequently used in genetic diversity analysis due to their codominant inheritance and rich polymorphism. More importantly, the integration of SSR technology with capillary fluorescence electrophoresis has significantly improved the safety, accuracy, and efficiency of genetic analysis, reducing the error rate associated with manual interpretation of results compared to traditional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [

2,

24,

25]. In this study, 142 alleles were identified in 659 Tartary buckwheat accessions using 15 SSR markers, with an average of 9.47 alleles in each locus. The number of alleles observed per SSR maker was obviously higher than those reported in previous studies [

2,

19,

20], suggesting that the SSR markers employed in our study were highly polymorphic. Among the 15 SSR markers, the PIC value ranged from 0.018 to 0.651, and the average was 0.391, which was lower than the values reported by Song [

2] and Li [

26]. The reason might be the larger number of Tartary buckwheat accessions in our study, some of which might exhibit a higher degree of homogenization. In fact, a few germplasms could not be distinguished by 15 pairs of SSR primers in our analysis. The genetic distance in 659 Tartary buckwheat accessions ranged from 0 to 3.496, and the mean I of 0.895 indicated that these Tartary buckwheat germplasm resources had abundant genetic diversity.

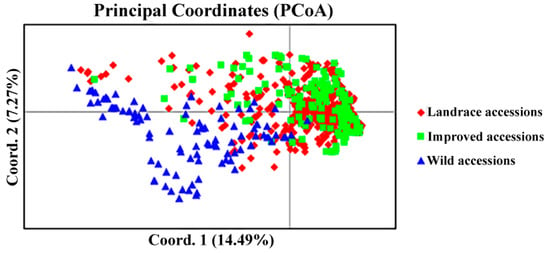

Exploring the genetic relationship among wild, landrace, and improved accessions would be crucial for fully utilizing the excellent Tartary buckwheat genetic resources to breed new varieties by formulating new hybrid combinations. In this study, we analyzed the genetic relationship among wild (101), landrace (383), and improved (175) Tartary buckwheat accessions. The I of wild accessions was significantly higher than those for landrace and improved accessions, while no significant differences were observed between the landrace and improved accessions. Similarly, the genetic distance between wild and landrace accessions (0.256) and between wild and improved accessions 0.281) was obviously notably larger than the distance between landrace and improved accessions (0.006). These findings indicate that the genetic diversity of wild accession is much higher than that of landrace and improved accessions, while there is no significant difference in genetic diversity between landrace and improved accessions. This is consistent with the previous study by Zhang et al., which identified notable genetic divergence between wild and cultivated accessions based on SNP markers analysis [

3,

27]. Furthermore, the results of population structure analysis, cluster analysis, and genetic identity analysis among wild, landrace, and improved accessions further support the difference in genetic diversity among these three accessions. Gene flow analysis found that significant gene exchange happened between landrace and improved accessions, while a lower gene exchange existed between wild and either landrace or improved accessions, respectively. This is consistent with the observation that wild accession has higher genetic diversity than that of landrace and improved accessions, and there is lower genetic variation between landrace and improved accessions. The lower genetic diversity between landrace and improved accessions may be closely related to the breeding technology where systemic breeding or Tartary buckwheat was the major approach, resulting in many breeding varieties directly derived from landrace varieties [

28]. Notably, in this study, the 659 Tartary buckwheat accessions were divided into seven subgroups. Interestingly, among the seven subgroups, we found that subgroup VII and subgroup I exhibited the largest genetic distance and genetic diversity. All members of subgroup VII belonged to wild Tartary buckwheat accessions. Subgroup I consisted of 14 landrace accessions (7 from Tibet, 4 from Sichuan, and 3 from Yunnan) and one improved accession (derived through systemic breeding from a Guizhou landrace) except 55 wild accessions. All these findings indicated that Tibet, in China, is most likely the origin center of cultivated Tartary buckwheat, consistent with previous research [

3,

27]. Zhang et al. [

3] and He et al. [

27] proposed that the domestication of Tartary buckwheat occurred independently in the southwestern and northern regions of China. Interestingly, in our study, we found that all subgroups, except subgroup VII and subgroup I, contain both southwestern landraces and northern landraces from China. This result contrasts with the findings of Zhang et al. [

3] and He et al. [

27]. The discrepancy may be attributed to the limited number of molecular markers used in our study or differences in the materials examined. To address this question, further genetic diversity analysis based on whole-genome SNPs is needed.

The construction of a core germplasm collection is a crucial step in genetic research. Generally, the core germplasm collection could be constructed using morphological data and molecular marker data. However, the morphological data can be easily affected by the developmental stages and the environment. In contrast, molecular markers provide abundant genetic variation and their stability is not affected by these variables. Thus, they have been widely used in core germplasm collection construction [

7,

22,

24,

29,

30]. Although several studies have performed the genetic diversity analysis of Tartary buckwheat using SSR markers [

1,

2,

19,

20,

21,

26], no core germplasm collection construction has yet been carried out until now. In this study, 165 germplasms (25.04%) from 659 accessions were selected to construct the core germplasm collection of Tartary buckwheat based on SSR markers, including 47 wild, 92 landrace, and 26 improved accessions. The 165 core accessions contained 92.25% (131/142) polymorphic loci of 15 SSR markers. The significance test among the core germplasm collection, the retention resources, and the original germplasm collection demonstrated that there were no significant genetic diversity differences. Furthermore, PCoA showed that core accessions were evenly distributed in the original accession. All these findings indicate that the 165 accessions selected as the core germplasm collection accurately represent the genetic diversity of the entire 659 accessions, and it can serve as the key resource for the diversity conservation. More importantly, it also can serve as the crucial resource for genetic improvement of Tartary buckwheat, which could be based on their genetic diversity, agronomic traits, quality traits, stress resistance traits. However, further investigation of these traits in the core germplasm is needed in future studies.