1. Introduction

Rabies is a viral disease spread through the saliva of infected mammals [

1]. It poses a serious public health challenge in over 150 countries and territories, particularly in Asia and Africa. Transmission occurs via bites, scratches, and licks to broken skin from a range of domestic and wild mammals [

1,

2]. Dog-mediated rabies accounts for over 99% of human cases [

1,

3]. Once clinical symptoms appear, rabies is almost invariably fatal [

4]. However, timely post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), involving wound care, multiple doses of rabies vaccine, and, for those previously unvaccinated, rabies immune globulin (RIG), effectively prevents the disease [

1,

5,

6]. Despite its safety and effectiveness, global disparities in access to rabies vaccine and RIG pose barriers for those in need [

7,

8,

9]. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), achieved through 2–3 doses of the rabies vaccine, primes the immune system, leading to an anamnestic response once a post-exposure rabies vaccine is administered [

5,

10,

11]. It simplifies PEP by reducing the required number of vaccine doses, and eliminating the need for RIG in the event of subsequent exposure [

7].

Rabies causes an estimated 59,000 human deaths annually worldwide. Cases of human rabies imported into non-endemic areas are comparatively rare, averaging 3.5 imported cases per year [

12]. However, due to their deadly nature, they frequently prompt public health alerts and media attention. A significantly higher number of travellers have potential rabies exposures, with an estimated incidence rate of 4 per 1000 travellers per month [

13]. Unfortunately, many of these travellers do not seek or receive complete PEP after potential exposures [

12,

14]. Access to RIG in particular is scarce, with only 5–20% of travellers receiving RIG in the country of exposure when indicated [

12]. This is underpinned by logistical factors involving RIG availability, cost, and storage, as well as lack of awareness about when RIG is indicated [

12].

The WHO recommends that travellers to rabies-endemic areas undergo an individual pre-travel risk assessment. This assessment should consider the remoteness and rabies epidemiology of the destination, as well as the duration of stay in rabies-endemic areas [

15]. Travellers intending to stay in remote rural areas with limited access to PEP, or those engaging in extensive outdoor activities that may increase their proximity to animals, should consider receiving PrEP before travelling [

15]. Even short-term travellers may be at risk of rabies, and PrEP may be considered based upon their intended activities and potential exposure risks [

16,

17]. Receiving PrEP before travel reduces the risk associated with limited PEP access abroad and helps conserve resources for endemic populations [

1]. Despite its benefits, the uptake of rabies PrEP remains limited due to factors such as limited awareness of rabies severity and preventive options, concerns about vaccine costs, and the logistical challenges of completing a vaccine schedule that requires 2–3 doses spaced over time [

18,

19].

Accessible health information is vital for empowering individuals to make informed decisions about their health, particularly in contexts involving disease prevention and management. In recent decades, there has been a notable shift towards using online health information as a preferred source globally [

20]. However, despite its potential to influence health-related decisions [

20] and promote healthier behaviours [

21], studies indicate online rabies information does not effectively facilitate pre-travel vaccination uptake among travellers to high-risk areas [

22,

23]. This highlights a gap between existing resources and user needs. Health literacy is crucial for navigating online health information [

24], yet readability, understandability, and actionability often fail to meet diverse health literacy needs [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. This disparity risks widening health inequities and further marginalising disadvantaged populations.

Our study aimed to assess the readability, understandability, actionability, and completeness of public-facing rabies information from various government and peak public health agency websites to identify gaps and opportunities for improvement. We hypothesised these resources exceed the recommended eighth-grade reading level, fall short of adequate thresholds for understandability and actionability, and do not fully address the information needs of the public.

3. Results

We assessed 22 sources of online rabies information from 15 government and public health agency websites.

Table 1 summarises key findings, including individual scores for readability understandability, actionability, and completeness, along with the median readability level and mean understandability, actionability, and completeness scores. The median word count and number of pages is also presented. Inter-rater agreement based on initial scoring (before discussion and adjustments) was deemed substantial (Cohen K > 0.61).

Most resources were single-page websites, with an overall median word count of 798 words. Resources with more text typically scored higher for completeness but had worse readability scores.

Median overall readability was grade 13 (IQR 11–14; range 10–15), with no resource meeting the ideal grade eight reading level for general audiences. Mean understandability was 66% (SD = 13%; range 42–87%), with 10 resources (46%) achieving the recommended 70% threshold. Mean actionability was 60% overall (12%; 33–83%), with only four resources (18%) meeting the 70% threshold.

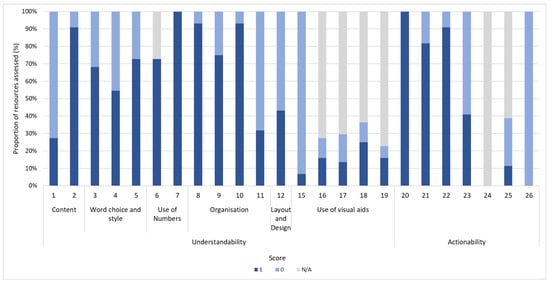

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of PEMAT-P scores by item across resources. While all resources identified at least one actionable step (item 20), no resource made meaningful use of visual aids to prompt user action (item 26) and only 9% (2/22) did so to make content more easily understood (item 15).

Mean completeness for general rabies information was 79% (13%; 50–100%), and for vaccine-specific information it was 36% (30%; 0–100%). A completeness score of ≥70% was achieved by 17 resources (77%) for general rabies information, and three resources (14%) for vaccine-specific information.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of completeness scores by item across all resources. For general rabies information, high proportions of ‘information not provided’ ratings were observed for item 11 (risk of disease following exposure; 77% scoring zero), item 10 (availability of treatment; 64%), and item 12 (diagnosis; 50%). For vaccine-specific information, items with high proportions of ‘information not provided’ ratings were item 18 (availability of different vaccine schedules; 86% scoring zero), item 21 (vaccine safety based on individual factors; 77%), item 22 (type of vaccine; 77%), item 16 (duration of protection; 73%), and item 20 (vaccine adverse events; 73%).

After the study period, the CDC rabies website was updated. We reassessed the new version using the same criteria. Compared to the previous version, median readability decreased from grade 14 (range: 9.9–17.8) to grade 13 (9.5–15.4). Mean understandability improved from 53% to 78%, while actionability remained at 83%. The proportion of items with partial or complete information decreased from 100% to 89% for general rabies information, and from 100% to 17% for vaccine-specific information.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically evaluate publicly available rabies information using validated measures of health information quality. Our findings highlight significant shortcomings in readability, actionability, understandability, and completeness of current resources for individuals with varying levels of health literacy.

None of the resources analysed met acceptable reading levels for general audiences (grade eight). Previous research from Australia and globally has shown that online public health information often exceeds recommended readability levels [

26,

28]. In particular, vaccine information often demands higher health literacy than other public health topics, such as mask use or physical distancing [

21,

23]. Poor readability can impede self-management and decision-making, particularly for individuals with lower health literacy levels [

26].

Our study also revealed a lack of actionable content in online rabies information, largely due to the inadequate use of visual aids and practical tools that support user action and decision-making. This aligns with findings from research on online COVID-19 resources and immunisation materials for migrants and refugees, which similarly highlighted deficiencies in actionability and a scarcity of tangible tools or visual aids [

27,

38]. The under-utilisation of visual aids is concerning, as they can greatly enhance understanding and decision-making, especially for individuals with low health literacy [

29,

38,

39,

40]. Effective visual aids, such as icon arrays, maps, and graphics, could enhance comprehension of rabies risk, vaccine efficacy, safety, and key prevention actions, such as wound washing and seeking medical assistance if exposed.

Due to the lack of validated tools for assessing information completeness in public-facing health resources, we created our own framework based on previous research [

36]. Our completeness assessment revealed significant gaps in rabies information across many resources, particularly in vaccine-specific details. These deficiencies may contribute to the low uptake of pre-travel rabies vaccination among travellers to endemic areas, as noted in previous studies [

22,

23,

41,

42]. Only three resources (from the CDC, NaTHNaC, and NHS) scored ≥70% in both general and vaccine-specific information. While the CDC and NaTHNaC resources were comprehensive, their lengthy content and university-equivalent (grade 14) reading levels limited accessibility. Recent updates to the CDC website improved understandability but reduced completeness, emphasising the need for a balanced approach that ensures health resources are both thorough and accessible, empowering members of the public to make well informed health decisions.

Decision-making around rabies pre-exposure vaccination (PrEP) is complex and influenced by individual, travel, and logistical factors [

43]. International opinions on which travellers should receive PrEP and the preferred schedules vary significantly [

44]. However, most guidance suggests that healthcare professionals conduct risk assessments for travellers to rabies-endemic areas, considering factors such as the likelihood of animal interaction and access to rabies PEP and emergency medical care. Children are often advised to receive PrEP due to their smaller stature, which increases the risk of exposures in higher-risk areas like the head and neck, as well as their tendency to interact with animals, and potential inability to report minor exposures [

43,

45]. PrEP is also often recommended for those undertaking longer trips, engaging in outdoor activities, or who will be more than 48 h away from facilities providing appropriate PEP [

15,

43]. Given the limited access to PEP in many popular travel destinations and the frequency of incomplete PEP [

8,

12], PrEP may be advisable for significantly more travellers than those who currently receive it. Ensuring that prospective travellers have access to clear and complete information enables them to make informed decisions about their health and safety whilst abroad.

Barriers to rabies PrEP include the multi-dose schedule, out-of-pocket costs, and lack of awareness [

43,

46,

47,

48,

49]. Multiple studies have highlighted cost as a major barrier [

47,

48,

49]. The cost of PrEP may be reduced by decreasing the number of doses or administering smaller doses via the intradermal (ID) route [

43,

50,

51]. Recent WHO guidelines now recommend a two-dose PrEP schedule instead of the previous three-dose regimen, but logistical and financial barriers persist [

15,

46]. Some studies suggest that a single dose of an intramuscular (IM) rabies vaccine can effectively prime the immune system and could potentially replace the current standard two-dose regimen [

52]. However, the efficacy of a single-dose schedule continues to be debated [

46,

53,

54] with current WHO guidelines still recommending a complete PEP course with RIG in the event of exposure after receiving a single pre-exposure dose [

15]. Immunity after a complete rabies pre-exposure vaccination schedule is long-lasting and boostable over long time intervals [

52], making rabies vaccination a valuable investment for travellers who frequently visit rabies-endemic areas.

Education strategies are essential for communicating rabies risk to travellers and encouraging timely pre-travel health consultations [

55]. Improved communication between travellers and clinicians can increase PrEP uptake and influence travellers to select lower risk destinations and activities [

55]. However, recent studies indicate that current pre-travel rabies education falls short of meeting travellers’ needs [

56]. While online health information has the potential to support informed decision-making about PrEP, its actual impact on PrEP uptake is currently limited [

22,

23]. The literature emphasises the need for better traveller education on rabies risks, vaccine availability, and risk-reducing behaviours, particularly for last minute travellers [

43,

45,

47,

56,

57,

58].

Efforts to address these issues include tools like Croughs and Soentjens’ risk scoring system to identify travellers eligible for PrEP [

44] and the CDC’s country classification system to guide healthcare providers and policymakers [

8]. While some publicly accessible websites (e.g., CDC, the WHO) offer country-specific rabies status information (

Supplementary S6), these resources are not specifically designed for the general public, and do not address other barriers to rabies vaccination, such as low risk perception [

23,

59].

To effectively tackle these challenges, there is a need for well-designed, public-facing online resources. Public health websites should be enhanced with clear, comprehensive information, utilising visual aids and accessible language. Given the complexities of rabies vaccine decision-making, developing targeted decision aids could significantly improve communication between travellers and healthcare providers and support travellers to make informed choices [

60,

61]. We advocate for further research into the factors influencing rabies PrEP uptake, as well as the development and evaluation of decision aids to support informed decision-making for rabies vaccination.

Finally, it is crucial to consider the implications of rabies PrEP uptake on global vaccine equity. The current global burden of rabies is highly inequitable, with daily fatalities from dog-mediated rabies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) far exceeding the number of deaths caused by dog-mediated rabies in high-income countries this century [

62]. In resource-limited settings, rabies biologics, particularly RIG, are scarce and highly valued [

63]. A full PEP course, involving multiple doses of a rabies vaccine and RIG, is costly to produce, and global supply is unevenly distributed, with limited availability in LMICs where populations are most at risk [

63,

64,

65]. The lack of RIG, particularly in rural areas of LMICs, often prevents patients in these areas from accessing life-saving treatment [

63]. This scarcity raises equity concerns, as travellers may use resources that are desperately needed by local residents [

64].

Dog vaccination is an effective method of combating rabies and was crucial in eliminating rabies in high-income countries. However, dog vaccination efforts remain limited in LMICs [

62]. While the WHO recommends PrEP for populations in highly endemic areas with limited access to PEP [

15], its availability and uptake remain low, hindered by economic and logistical challenges [

64]. Travellers to rabies-endemic areas arguably have an ethical responsibility to consider rabies PrEP, not only to protect themselves, but also to potentially conserve RIG for local populations and alleviate the burden on healthcare systems in LMICs. Providing travellers with complete, understandable information, such as an online decision aid, may improve PrEP uptake and help conserve critical resources. Additionally, rabies PrEP reduces the risk of travellers facing challenges in accessing life-saving PEP while abroad or needing to alter travel plans to obtain appropriate PEP [

43].

4.1. Strengths, Limitations, and Generalisability

Our study used objective and validated tools (SMOG index and PEMAT-P) to evaluate readability, understandability, and actionability. However, it is important to acknowledge the inherent limitations of these tools. Many traditional readability formulas, while useful, can oversimplify comprehension by focusing solely on text features like word length and sentence structure. We chose to use the SMOG index due to its ease of use and suitability for healthcare applications, as it tends to provide consistent results and has a lower likelihood of underestimating reading levels compared to other formulas [

66]. Additionally, we used the SHeLL Health Literacy editor, which was shown to provide more accurate assessments than other online readability calculators [

67].

To address some limitations associated with relying solely on readability, we combined these assessments with evaluations of understandability, actionability, and completeness. While PEMAT is validated by both healthcare professionals and lay people, it can be subject to individual interpretation. To mitigate this, we employed two independent evaluators and an adjudication process for discrepancies, achieving good inter-rater agreement before adjudication. To assess the completeness of rabies information, we used a purpose-built framework, developed with content experts, a consumer representative, and prior research. This approach adds a unique strength that distinguishes our work from other health literacy studies.

While our analysis focused on English-language sources from authorised websites in countries with rabies profiles similar to Australia, this scope may not fully represent the information available in countries where rabies is endemic or present in companion animals. Additionally, we did not examine commercial sources, such as travel clinic websites, which the public might also use, further limiting the generalisability of our findings.

4.2. Implications

Our study adds valuable insights into the broader body of evidence concerning publicly available sources of health information and health literacy, which may inform best practice guidelines for online health information. These findings will directly inform our development of a rabies vaccine decision aid. We also plan to report findings to the administrators of the analysed resources, potentially prompting updates and improvements.