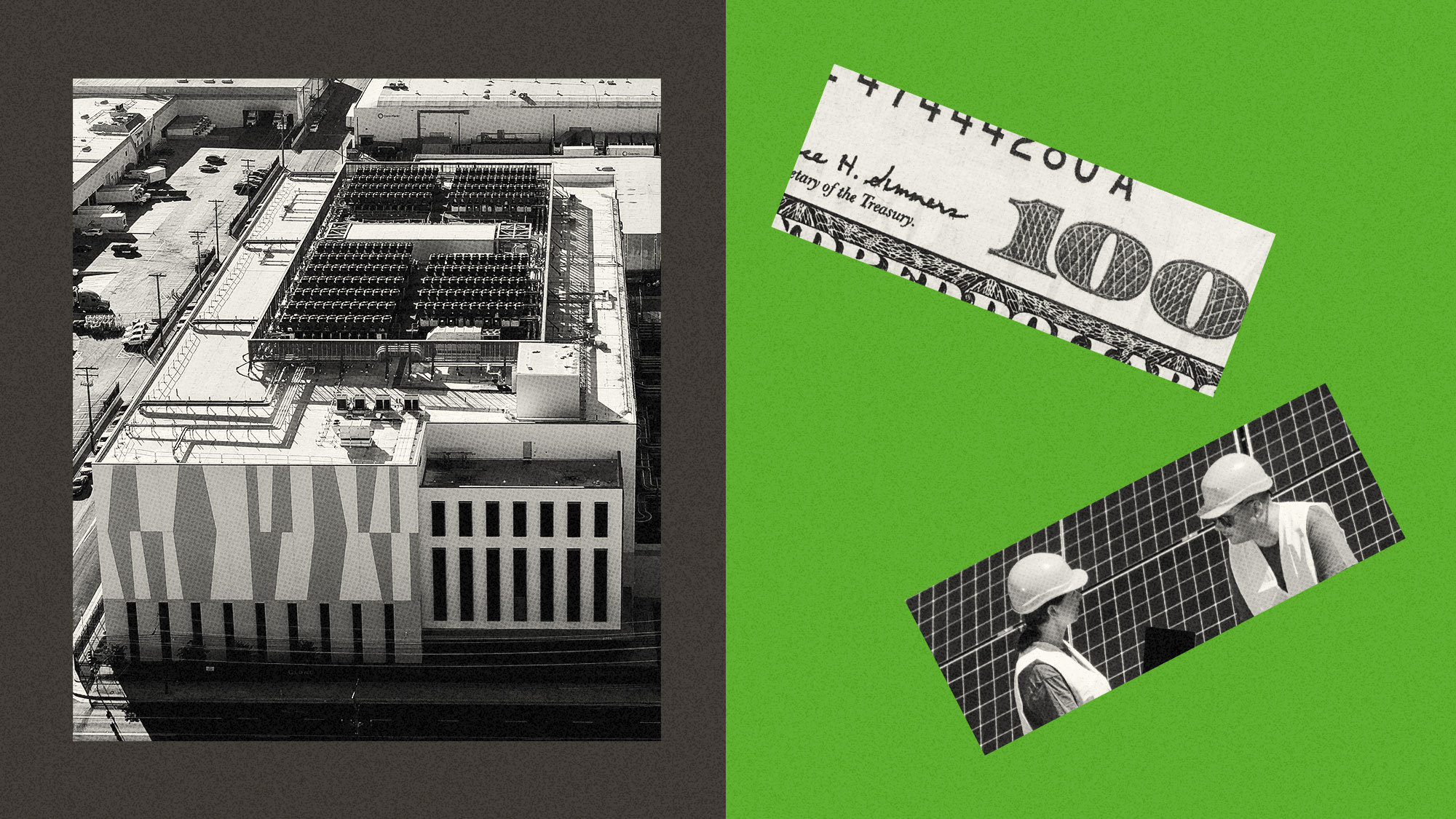

With community opposition growing, data center backers are going on a full-scale public relations blitz. Around Christmas in Virginia, which boasts the highest concentration of data centers in the country, one advertisement seemed to air nonstop. “Virginia’s data centers are … investing billions in clean energy,” a voiceover intoned over sweeping shots of shiny solar panels. “Creating good-paying jobs” — cue men in yellow safety vests and hard hats — “and building a better energy future.”

The ad was sponsored by Virginia Connects, an industry-affiliated group that spent at least $700,000 on digital marketing in the state in fiscal year 2024. The spot emphasized that data centers are paying their own energy costs, framing this as a buffer that might help lower residential bills, and portrayed the facilities as engines of local job creation.

The reality is murkier. Although industry groups claim that each new data center creates “dozens to hundreds” of “high-wage, high-skill jobs,” some researchers say data centers generate far fewer jobs than other industries, such as manufacturing and warehousing. Greg LeRoy, the founder of the research and advocacy group Good Jobs First, said that in his first major study of data center jobs nine years ago, he found that developers pocketed well over a million dollars in state subsidies for every permanent job they created. With the rise of hyperscalers, LeRoy said, that number is “still very much in the ballpark.”

Other experts reflect that finding. A 2025 brief from University of Michigan researchers put it bluntly: “Data centers do not bring high-paying tech jobs to local communities.” A recent analysis from Food & Water Watch, a nonprofit tracking corporate overreach, found that in Virginia, the investment required to create a permanent data center job was nearly 100 times higher than what was required to create comparable jobs in other industries.

“Data centers are the extreme of hyper-capital intensity in manufacturing,” LeRoy said. “Once they’re built, the number of people monitoring them is really small.” Contractors may be called in if something breaks, and equipment is replaced every few years. “But that’s not permanent labor,” he said.

Jon Hukill, a spokesperson for the Data Center Coalition, the industry lobbying group that established Virginia Connects in 2024, said that the industry “is committed to paying its full cost of service for the energy it uses” and is trying to“meet this moment in a way that supports both data center development and an affordable, reliable electricity grid for all customers.” Nationally, Hukill said, the industry “supported 4.7 million jobs and contributed $162 billion in federal, state, and local taxes in 2023.”

Dozens of community groups across the country have mobilized against data center buildout, citing fears that the facilities will drain water supplies, overwhelm electric grids, and pollute the air around them. According to Data Center Watch, a project run by AI security company 10a labs, nearly 200 community groups are currently active and have blocked or delayed 20 data center projects representing $98 billion of potential investment between April and June 2025 alone.

The backlash has exposed a growing image problem for the AI industry. “Too often, we’re portrayed as energy-hungry, water-intensive, and environmentally damaging,” data center marketer Steve Lim recently wrote. That narrative, he argued, “misrepresents our role in society and potentially hinders our ability to grow.” In response, the industry is stepping up its messaging.

Some developers, like Starwood Digital Ventures in Delaware, are turning to Facebook ads to make their case to residents. Its ads make the case that data center development might help keep property taxes low, bring jobs to Delaware, and protect the integrity of nearby wetlands. According to reporting from Spotlight Delaware, the company has also boasted that it will create three times as many jobs as it initially told local officials.

Nationally, Meta has spent months running TV spots showcasing data center work as a viable replacement for lost industrial and farming jobs. One advertisement spotlights the small city of Altoona, Iowa. “I grew up in Altoona, and I wanted my kids to be able to do the same,” a voice narrates over softly-lit scenes of small-town Americana: a Route 66 diner, a farm, and a water tower. “So, when work started to slow down, we looked for new opportunities … and we welcomed Meta, which opened a data center in our town. Now, we’re bringing jobs here — for us, and for our next generation.” The advertisement ends with a promise superimposed over images of a football game: “Meta is investing $600 billion in American infrastructure and jobs.”

In reality, Altoona’s data center is a hulking, windowless, warehouse complex that broke ground in 2013, long before the current data center boom. Altoona is not quite the beleaguered farm town Meta’s advertisements portray but a suburb of 19,000, roughly 16 minutes from downtown Des Moines, the most populous city in Iowa. Meta says it has supported “400+ operational jobs” in Altoona. In comparison, the local casino employs nearly 1,000 residents, according to the local economic development agency.

Ultimately, those details may not matter much to the ad’s intended audience. As Politico reported, the advertisement may have been targeted at policymakers on the coasts more than the residents of towns like Altoona. Meta has spent at least $5 million airing the spot in places like Sacramento and Washington, D.C.

The community backlash has also made data centers a political flashpoint. In Virginia, Abigail Spanberger won November’s gubernatorial election in part on promises to regulate the industry and make developers pay their “fair share” of the electricity they use. State lawmakers also considered 30 bills attempting to regulate data centers. In response to concerns about rising electricity prices, Virginia regulators approved a new rate structure for AI data centers and other large electricity users. The changes, which will take effect in 2027, are designed to protect household customers from costs associated with data center expansion.

These developments may only encourage companies to spend more on image-building. In Virginia’s Data Center Alley, the ads show no sign of stopping. Elena Schlossberg, an anti-data-center activist based in Prince William County, says her mailbox has been flooded with fliers from Virginia Connects for the past eight months.

The promises of lower electric bills, good jobs, and climate responsibility, she said, remind her of cigarette ads she saw decades ago touting the health benefits of smoking. But Schlossberg isn’t sure the marketing’s going to work. One recent poll showed that 73 percent of Virginians blame data centers for their rising electricity costs.

“There’s no putting the toothpaste back in the tube,” she said. “People already know we’re still covering their costs. People know that.”

Source link

Sophie Hurwitz grist.org