The beeping of old dialysis machines at the National Kidney Center in Kathmandu never stops. Nurses in dark blue scrubs rush around tending to the 55 people having their blood cleaned at any given time while cleaners squeeze by carrying stained sheets and buckets of bloody catheters. The facility, located alongside a major thoroughfare in the Nepalese capital, runs three dialysis sittings daily. That’s as many as 165 patients every day. Most visit three times a week, and will do so for the rest of their lives. “Otherwise they will die,” said Dr. Rishi Kumar Kafle, the nephrologist who founded the clinic 28 years ago.

Each patient sits snuggled in a blanket, one arm connected to a device the size of a small refrigerator that filters toxins from their blood, an essential task their kidneys can no longer perform. One of them is 30-year-old Surendra Tamang, who, like many young Nepalese men, left his family to work in the Persian Gulf.

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

Tamang was just 22 when he moved to Qatar hoping to earn the money to build a better life. For six years, he worked 12-hour shifts assembling scaffolding in relentless heat that could go as high as 50 degrees Celsius, or 122 degrees Fahrenheit. It was hard work, but he was young and strong. One day in 2023, he began feeling short of breath and noticed his hands swelling. He didn’t yet know that these were two common symptoms of end-stage kidney failure. After he was diagnosed in Qatar, his employer sent him back to Nepal. He hasn’t worked since. “I’m weak, I can’t do anything,” Tamang said after a dialysis session in early October.

He is among the 7.5 percent of Nepalis — the majority of them men — who have left the country in search of work. Half of these migrant workers are 20 to 29 years old, and 14 percent went to the Middle East. More than 1 million Nepalese workers currently live in the Gulf, along with millions of others from across Asia. Once there, these workers often face systemic exploitation from companies seeking cheap and efficient labor to build everything from skyscrapers to football stadiums. They are often paid less than promised, frequently have their wages and passports withheld, and live in overcrowded housing while facing unsafe working conditions. Many suffer cardiac arrest or return to their home countries with other health problems. Of the 138 patients admitted to the dialysis clinic in Kathmandu in the past six months, more than 20 percent had worked in the Gulf. “A young boy who was healthy goes there and in two, three years he comes back with kidney failure,” Kafle said.

These men are part of a silent epidemic affecting people who toil in extreme temperatures — from sugarcane cutters in Central America to agricultural workers in South Asia. A 2022 study found that high temperatures combined with physically demanding work are driving a surge in chronic kidney disease, which is already one of the world’s fastest-growing killers and on track to become the fifth largest cause of premature death by 2050. Yet, it had remained largely invisible to both the public and policymakers until May of this year, when the World Health Organization passed a landmark resolution recognizing the need to prioritize kidney care — even though simple measures such as frequent breaks and access to drinking water could prevent thousands of deaths. What’s emerging in Nepal is a glimpse into how climate, labor, and inequality collide, leaving some of the most vulnerable workers dangerously exposed as the world warms.

After dialysis, Tamang — a soft-spoken man with a shy smile — sat on a bench outside the clinic recovering from his last treatment of the week. The government provides patients like him with free dialysis, and offers patients the equivalent of about $35 a month to cover medication, Kafle said, but most struggle to make ends meet. Tamang once imagined earning enough to help support his family. Now he lives alone in Kathmandu — he has to stay close to the clinic — and spends 12 hours a week tethered to a machine that does what his kidneys cannot. “I would like to work,” he said quietly through a translator, “but it’s not possible.”

Doctors in Nepal have discovered what’s happening to young men like Tamang: Years of relentless heat, dehydration, and physically demanding work have gradually, then suddenly, destroyed their kidneys — a condition called chronic kidney disease, or CKD. The illness progresses through five stages, and when these organs fail, they can no longer perform critical functions like removing waste from the blood and helping maintain normal blood pressure. The damage is permanent, and without dialysis or a transplant, fatal. CKD has quietly become one of the fastest-growing causes of death, affecting roughly one in 10 adults — some 674 million people worldwide, a World Health Organization spokesperson told Grist in an email. But not everyone is affected equally: Nine out of 10 individuals with CKD live in low-income settings with poor access to health care.

The early symptoms of CKD can be deceptively mild: swelling of the limbs, fatigue, loss of appetite, trouble sleeping. In most cases, people don’t even experience them until it’s too late and their kidneys are already failing. The most common causes have normally been diabetes or high blood pressure, but scientists and physicians have begun tracing a clear link between rising heat and this mounting crisis. In Brazil, a nationwide analysis using health data from 2000 to 2015 showed that every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degree Fahrenheit) rise in daily average temperature increased hospitalizations for renal disease by nearly 1 percent. A 2022 study in New York City found that days with extreme heat led to a 2 to 3 percent jump in hospital visits for renal issues. “When there are heat waves, our emergency rooms become busy taking care of people with kidney injury,” said Dr. Meera Nair Harhay, a nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Mohammed Mahjoub / AFP via Getty Images

A decade ago, Kafle and his colleagues began noticing that many dialysis patients were young men who’d worked construction jobs in the Middle East — a pattern that soon became too stark to ignore. What seems to be the “mystery trigger” is work-related heat stress. Researchers from the University of Gothenburg and other institutions have since established an undeniable connection. In a forthcoming technical report, they analyzed the histories of 404 patients at five dialysis clinics throughout Kathmandu and found that one out of three male patients on dialysis had worked abroad in countries with hot climates, most of them in Saudi Arabia, Dubai, Qatar, Kuwait, Malaysia, and India.

Many had to start dialysis in their early 30s, an average of 17 years earlier than patients who never migrated for work. Half of them started to experience symptoms and were diagnosed in the country where they worked, said Kristina Jakobsson, a senior researcher at the School of Public Health and Community Medicine at the University of Gothenburg. When a worker is exposed to the sun while performing straining tasks, their internal temperature rises, causing sweating, fluid loss, and, eventually, dehydration. Heat stress occurs when the body cannot shed that excess heat. This puts significant strain on the kidneys and their ability to regulate the body’s fluid balance, electrolytes, and waste removal. If the body temperature and hydration levels are not restored by, say, drinking water and taking a break in the shade, it may lead to kidney injury, said Jakobsson.

By some estimates, 70 percent of workers worldwide are exposed to excessive heat each year. With the world on track to warm between 4 and 5 degrees Fahrenheit above preindustrial levels this century — and the Persian Gulf heating almost twice as fast as the global average — the strain on the human body is mounting.

For nurse Deepa Adhikari, it’s the faces she sees at the National Kidney Center that reveal the true cost of CKD. In her 14 years there, she has seen the patients in her ward give way to an increasing number of young men. Apart from grappling with the physical symptoms of their disease, many suffer the emotional strain of not being able to work and of feeling like a burden to their families. “The patients are financially, physically, and emotionally stressed,” she said.

Inside the clinic, which smells strongly of blood and vinegary cleaning products, Adhikari tends to each person with grace, carefully inserting needles into already bruised arms while offering kind words of encouragement. The job requires that she be as much a counselor as a nurse.

A young man waits for his dialysis treatment at the National Kidney Center in Kathmandu, Nepal, where up to 165 patients pass every day. Inside, a nurse tends to a patient with bad bruising and scarring from years of dialysis treatment. Orderlies squeeze between nurses and patients to keep things clean, disposing of waste such as bloody catheters. Natalie Donback

“Chronic illness is very traumatizing for the family and the patients,” Adhikari said. “We try to give emotional support.” It’s Dashain, the country’s most important holiday, yet she’s still on duty — checking catheters, managing fluid levels, and bringing some measure of comfort. The exhaustion shows in her posture, but she keeps moving. “Physically we are stressed,” she said, “but in the corner of my heart, I’m satisfied for providing care.”

Her patients include Buddhi Bahadur Kami and Kul Bahadur Dulal, whose lives were upended after years of working in Saudi Arabia’s relentless heat. (The two men spoke through a translator.) Kami, who is 41, spent 11 years painting large diesel storage tanks, hoping to earn enough to cover tuition for his children back home. He and his coworkers endured long hours in very hot conditions and were given water only every few hours despite sweating through thick uniforms and protective masks. Dulal, 46, drove trucks across the desert for a decade, living in a company camp with more than 200 other migrants. Both returned to Nepal with failed kidneys. “I had made a lot of money, but it’s all gone to paying for treatment,” Dulal said. To help with the health care costs, his son took a construction job in Dubai — only to return home after breaking his leg in a fall from a bunk, continuing the vicious cycle of poverty that sent him and his father abroad in the first place.

Natalie Donback

For laborers like Kami and Dulal, the pressure to perform — and to send as much money home as possible — is compounded by a power imbalance with employers and the constant fear of deportation, said Dr. Barrak Alahmad, director of the Occupational Health and Climate Change Program at Harvard University. Many arrive indebted to the companies that recruited them, so “if you’re sick, you’re on the next plane back to Kathmandu,” he said. “Someone else is picking up the tab and these are the small, underfunded dialysis clinics in Kathmandu.”

The heat these men endure is compounded by precarious living conditions, constant fatigue, and poor diets that further stress the kidneys. The 24 million migrants living in Arab states — many of them from Nepal, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan — often live in cramped quarters with few healthy food options, little opportunity for exercise, and chronic sleep deprivation. Several dialysis patients told Grist they consumed energy drinks and soda rather than water, as they were easier to come by and refreshing during long shifts. While some enjoy free health care, few can take the time to use it. “They’re pressured into this rat wheel of being on the job all the time — you really minimize your health in order to keep working until you drop,” said Alahmad.

“Migrant workers are at the forefront of climate change right now,” he added. They are first hit at home, where floods and other disasters often destroy their homes and livelihoods. Then they’re hit again in the Persian Gulf, where they endure unbearable heat. “I call this the double whammy of climate change on migrant workers,” he added. “In a way, chronic kidney failure from heat becomes the ultimate marker of climate change.”

Marwan Naamani / AFP via Getty Images

The very countries recruiting and hiring these men fuel the heat that sicken them. The Middle East is home to five of the world’s 10 largest oil producers; many of these nations have grown rich from fossil fuels. They are now using that wealth to build massive infrastructure projects requiring a constant supply of cheap labor, from soccer stadiums ahead of the 2034 World Cup in Saudi Arabia to a new Disney theme park in Abu Dhabi. “They are the ones creating the ultimate harm, and they have minimal responsibility,” said Michael Page of Human Rights Watch. Despite the risks, protections for these workers remain dangerously weak. “We need states to keep up,” and put pressure on the companies hiring these men, Page said.

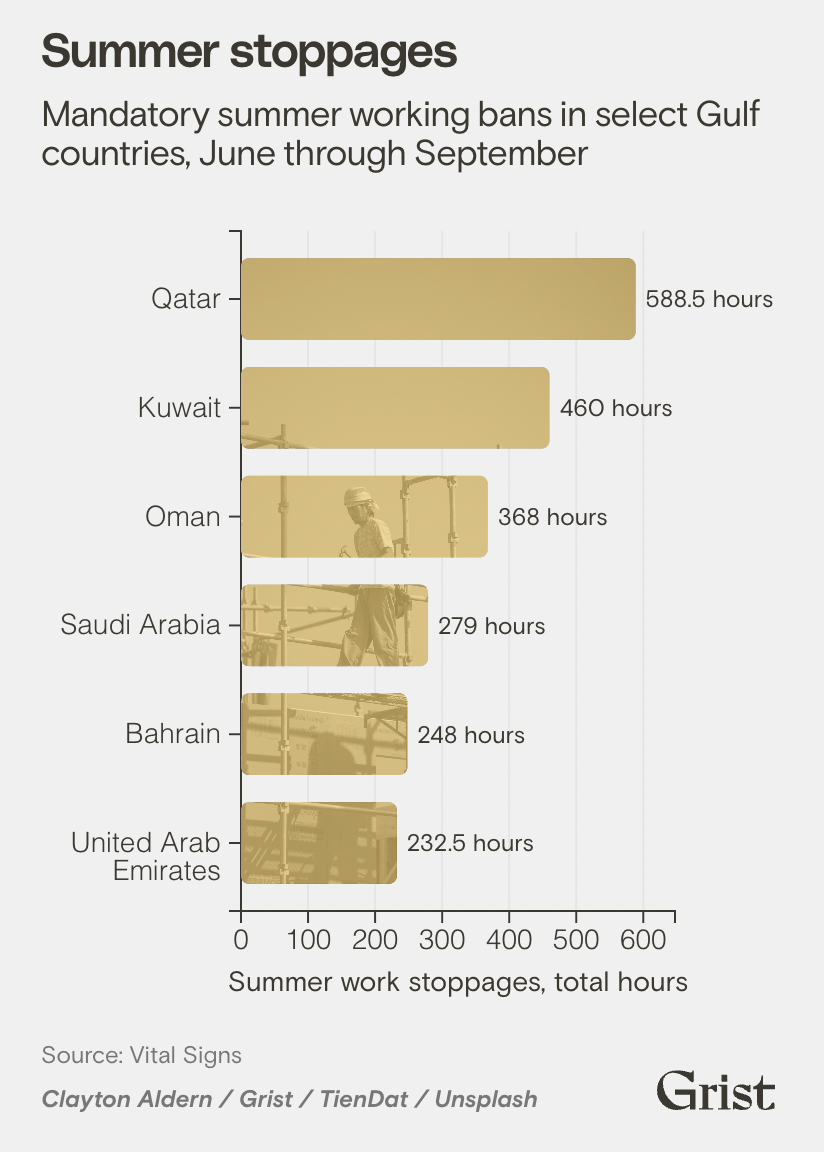

Some Gulf countries have barred working at midday during the hottest months, but experts like Alahmad say these rules are simplistic and do little to protect workers. “The problem with these bans,” he said, “is that they assume you can’t have a heat stroke at 10:59 a.m., but you can at 11:00.”

As if to prove the point, midday temperatures in May reached almost 125 degrees Fahrenheit in the United Arab Emirates, weeks before the summertime work ban went into effect on June 15. True protection, Alahmad and others say, means more than simply avoiding the hottest hours. It means providing ample rest, shade, and water throughout the work day, as well as frequent check ups and testing to spot kidney issues early on.

Mandatory summer working bans in select Gulf countries, June through September

Rather than apply a universal standard, health experts say, regulations should be based on each worker’s specific risk. That means considering the wet bulb globe temperature — a measure based on temperature, humidity, wind speed, sun angle, and other factors — and the laborer’s metabolic workload. Such an approach requires continuous monitoring of those conditions, something few companies are equipped, or compelled, to do.

Qatar has taken some steps. A 2021 ministerial order expanded work bans and required companies to halt labor when the wet bulb globe temperature exceeds 32.1 degrees Celcius, or 89.8 degrees Fahrenheit. While inspectors are equipped to measure the index, companies are not legally required to continuously measure it at their work sites, explained Michail Kandarakis of the International Labour Organization, the United Nations agency responsible for setting labor standards and supporting decent working conditions.

The 2021 order also recognizes employees’ right to stop working if they feel unwell, and mandates annual health checks and risk assessments. Yet, the information that could guide more comprehensive reform remains sparse. Kandarkis cited a need for stronger data collection systems to understand when and how workers get sick — or even die — from heat exposure. Many deaths in Saudi Arabia are, for example, deemed natural and neither investigated or compensated, according to Human Rights Watch.

Halfway around the world from the dialysis wards of Kathmandu, a promising solution is emerging from the sugarcane fields of Nicaragua. There, La Isla Network, a research organization working to address heat stress in workers, has spent years trying to prove that kidney damage, let alone failure, is not an inevitable result of working under an unforgiving sun. By turning plantations into laboratories — tracking workers’ heart rates, body temperatures, and water intake — they showed that prevention is possible when employers make it a priority.

This work started more than a decade ago, when villages throughout Central America were losing their men to renal failure before they reached middle age. Filmmaker-turned-researcher Jason Glaser arrived to investigate and eventually founded La Isla Network in 2012. His mind was set on finding ways to tackle the preventable disease and getting data that could help inform an intervention. The organization’s findings helped make clear that CKD is an occupational hazard in need of attention — and a warning of how climate change could soon impact the health of outdoor workers everywhere.

Sam Tarling / Corbis via Getty Images

In 2017, on the same fields where so many workers had gotten ill, La Isla Network launched a program to keep their body temperatures below 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit to reduce the risk of heat strain and subsequent kidney damage. To do that, Glaser and his team reimagined the workday: mandatory breaks, a higher rest-to-work ratio, and greater access to shade and hydration. The results were dramatic: Incident kidney injury — defined as a decline in kidney function over a certain period, like a harvest — plummeted by 70 percent. The interventions also clearly improved productivity, which climbed 19 percent thanks to fewer absences and accidents.

“When a solution is sitting there that’s a big win-win,” Glaser said. “What’s the holdup? There are answers, but they’re not being employed.” He believes the rich nations of the Persian Gulf could easily implement the approach his organization has developed to protect workers.

Mandated life insurance is another easy way employers could better support migrant workers and their families. When a laborer dies in the Gulf, his family rarely receives compensation — and the cost of repatriation often falls on relatives who have just lost their primary breadwinner, explained Page.

Maharjan / NurPhoto via Getty Images

The trickier problem is figuring out who pays for the renal care these men require. Gulf states, Page said, “are essentially treating these migrant workers who have kidney failure as disposable, then throwing the cost on countries like Nepal or Bangladesh. If there wasn’t free health care that provided dialysis, some of these workers would probably die.”

The disparity in health care budgets between the nations welcoming these laborers and the countries that end up treating them is staggering. Last year, Saudi Arabia spent the equivalent of $57 billion for health and social development. In Nepal, the government spent the equivalent of $605 million on public health. The Ministry of Health in Nepal reimburses the National Kidney Center just $18 for each dialysis session, Kafle said, adding that the ministry hasn’t paid the center in eight months and overworked nurses like Adhikari haven’t been paid for the past two months.

Kafle, struggling to keep his clinic afloat and pay suppliers on time, said the imbalance must be addressed. He believes Gulf countries — whose thriving economies depend on migrant labor — should help fund transplants and education and safety campaigns in Nepal. “All over the world, the issue of awareness is a big problem,” he said, noting that many workers still don’t know the dangers of dehydration and extreme heat.

Natalie Donback

By the time most workers with CKD come back home, they’ve already lost 80 to 90 percent of their kidney function, which is too late for anything but lifetime dialysis or a transplant. That is why Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population hopes to shift its scarce resources toward prevention and early screening, including more stringent testing of migrant workers before they depart and when they return to visit family. “Once we have more screening, the number of kidney failures will go down,” said Kafle, who would like to see Gulf employers provide regular checkups and simple blood tests that could catch kidney damage early. “Treatment is not the answer,” he added. “Prevention is.”

Ultimately, for men like Surendra Tamang, a transplant is the only real chance to regain a normal life — and, according to health officials, the most cost-effective compared to dialysis. Still, the demand for the organ far exceeds the supply, and patients on the transplant list can expect to wait at least six months to get one unless they can find their own donor. Until then, Tamang will continue to visit the National Kidney Center three times a week for the rest of his life. The alternative would be fatal.

Source link

Natalie Donback grist.org