Humans have been leaving their mark upon Earth for almost as long as we’ve existed. But over the last 70 years — little more than moments in the 300,000-year history of Homo sapiens — the amount of stuff we’ve added to the planet has erupted in volume, surpassing living organisms in both mass and diversity. And while this cascade has appeared in a flash, geologically speaking, it will persist for tens of millions of years — if not longer.

The long-term legacy of civilization has tickled the imagination of science fiction writers from Isaac Asimov to the minds behind the cartoon sitcom Futurama. But the intricacies of how our artifacts might fossilize or decay has been largely left to speculation. What geologic evidence will be offered by the hundreds of thousands of synthetic materials humans have engineered? Will polyester underwear, just one item among the 92 million tons of textiles cast aside every year, squashed in layers of strata over millennia, be recognizable as clothing to future archaeologists? Could the unending network of roads, the 3 billion miles of copper wiring, and other detritus reveal the technological interconnectedness of modern life?

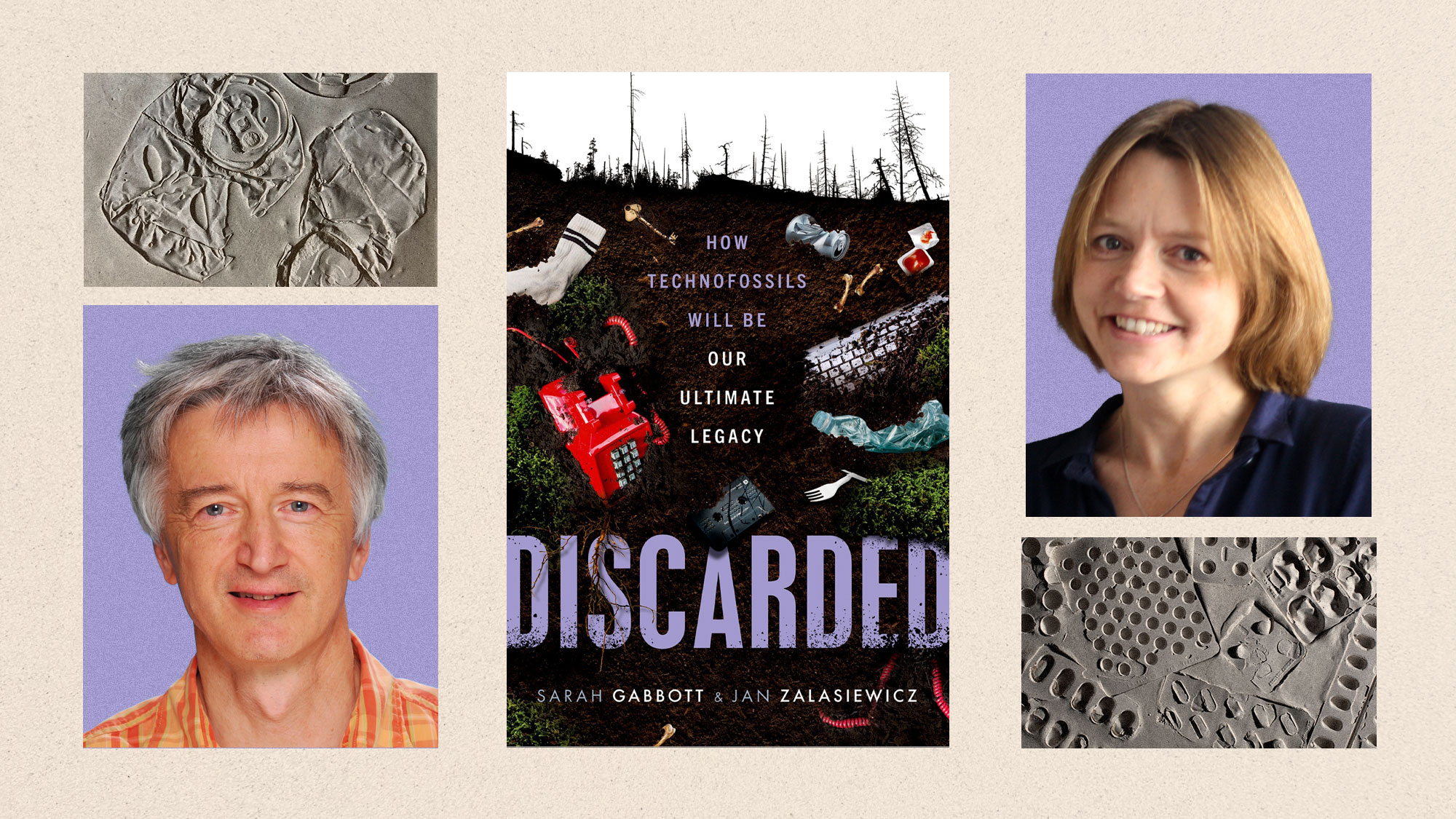

In their upcoming book, Discarded: How Technofossils Will be Our Ultimate Legacy, paleontologist Sarah Gabbott and geologist Jan Zalasiewicz explore these questions. They reference the minerals, metals, and fossils already in the archeological record to provide compelling evidence of how everyday objects like ballpoint pens or the chicken bones from dinner might endure for eons. By their measure, rising seas and sinking land could preserve entire cities like New Orleans, leaving them for scholars in the distant future to puzzle over, much like current ones ponder Pompeii.

Gabbott and Zalasiewicz use the term technofossils to describe the objects that will leave a distinct mark on Earth’s geologic record. These remnants are part of the technosphere, a concept geologist Peter Haff popularized to describe the mass of everything humanity has created or changed, akin to the natural world’s biosphere. Beyond these artifacts, the industries that created them have left their own scars upon the planet: Atmospheric signatures in carbon isotopes, fly ash from burning fossil fuels, and radioactive waste will be among the clues left for geochemists studying what Zalasiewicz calls our “carbon extravaganza” and “energy binge.”

Grist caught up with Gabbott and Zalasiewicz to discuss what today’s trash will tell tomorrow’s archaeologists, geologists, and others about the lives we led. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Why did you decide to write the book?

Jan Zalasiewicz: For a while now, I’ve had an interest in the geology of the future — how the things we do and make on Earth right now will have an impact in the far future. There’s always been this question of the stuff that we make: The chairs, tables, cars, toothbrushes, and all of that. Something will happen to them, but what? The answer can really be quite subtle and complicated. That’s where it seemed the perfect opportunity to team up with Sarah, who has developed huge expertise in looking at some of the world’s best preserved fossils and in working out how they got preserved and what they can tell us.

Sarah Gabbott: In my career, I’ve been looking backward in time at ancient fossils. Now, I can use that experience and apply it in fast forward to the stuff we make today. Jan has been pivotal in the exploration of the idea of the Anthropocene and this new kind of era of geological time, so it’s a case where we’re the perfect team to address these issues.

Q: How did you go about sleuthing out the fate of our technofossils?

JZ: We look back from stuff that we make now to ancient analogs, or near analogs, that we can use to [compare]. But there are others where we had to really scratch our heads and think how things might behave. Metals are a case in point: We’re used to living with iron, steel, copper, and aluminum, but there are not many pure metals in nature. We really had to think through the chemistry and physics of how these things might behave. Minerals were even worse — Earth has around 5,000 natural minerals but only a few are common. Humans have made more than 200,000 of new mineral types. There’s no geologic analog for working out how they will behave centuries, or millions of years, from now.

SG: Anything that relates back to life has an easy analog. The fast food chapter, for example, focuses quite a lot on chickens because, obviously, there are loads and loads of chickens around today, and humans changed their evolution. We could think about fossil feathers, because they preserve so well.

Another one that was interesting was “fossil fashion”. You can consider natural materials, like hemp and cotton, and it’s surprising how little of that stuff preserves well. But then you go back far, far in time and you’ve got dinosaur and snake skins that are so beautifully preserved from 10 million years ago that you can even tell what color they were in life.

Q: You highlight some surprising examples of technofossils, like children’s drawings, pencils, and ballpoint pens. What drew you to them?

SG: The inspiration came from all different lines of thinking. With the pencil and ballpoint pen, the train of thought started with, “What aspect of our writing will last the test of time?” We may tend to think that the future fossil record of what we write will be bound up in computers and hard drives, but they can be easily corrupted and hard to decode. So, I started thinking about writing. The ballpoint pen, the graphite in pencils — ink can last a long time, but graphite can last billions and billions of years.

Jeff J Mitchell / Getty Images

Q: What about plastics?

SG: Plastic has a chemical backbone that is incredibly strong and difficult to change, but it has only really been around since the 1900s. We haven’t had long enough to run experiments to really work out how long this stuff is going to last. If you want to work out what might happen to it under extreme conditions, we can stick it in very hot conditions, or expose it to really extreme UV light. But let’s be honest, most plastic out there is litter – it’s exposed to normal conditions.

So we started asking some basic questions, running basic experiments on plastic bags, and thinking about fossil analogs. There are polymers that life makes that are almost identical, chemically. We can use the fossil analog to say of this stuff, “If you take it out of sunlight and away from heat, it is going to last 50 million years plus.” Some of it is going to make microplastics, some of it will get broken down by sunlight, but all these plastic materials that are getting buried are going to potentially last millions and millions of years.

JZ: Take any old plastic debris in a landfill site where cement has been dumped over the plastic — that plastic would be so well protected that it’s very hard to see how that plastic will disappear. It will stay there. The only way it will change is, as it is buried deeper and deeper, the plastic will slowly begin to lose some of its hydrogen, lose some of its oxygen, and it will carbonize and turn into a more brittle kind of carbon film that will still preserve a very detailed structure. We know that’s exactly how fossils behave.

Q: So much of humanity’s waste ends up in landfills. Should we think of these repositories as time capsules or time bombs?

SG: In places where landfills are managed, each layer is wrapped up in plastic and they tend to be fairly dry environments away from sunlight. Without water, bacteria can’t thrive, and without bacteria you don’t get decay, so a lot of the stuff is going to sit around mummifying. But they’re also, potentially, a toxic time bomb, because of course we’ve built a lot of landfills on coastal and river floodplains – in the U.S., you’ve got at least 50,000 landfills along coastlines. So as sea level rises, there’s a massive problem: The degree to which those are going to be buried safely over time, or whether they’re going to erode and disgorge of all that stuff into the oceans, we don’t really know.

Q: Can people of the future mine our refuse as a resource?

JZ: That should, of course, be pursued, but it’ll be tricky and complicated. Each landfill is going to be different and present different problems.

SG: Basically, we chuck everything in landfills, and records of what goes in and where it goes are very, very minimal. You say, “OK, I’ll mine it for plastic and then I’ll recycle that plastic. But if there’s food waste around, or metal waste, forever chemicals, and so forth — all this stuff is kind of a chemical cocktail that can contaminate the stuff you want to take out of the landfill.

Q: You mentioned sea level rise. In what other ways is climate change reshaping the geologic record?

JZ: We know ice cores and the strata within ice, on Greenland and Antarctica in particular, give us such an important part of our climate history through the chemistry of air bubbles trapped in the ice. That is helping us predict climate now, but the flip side of that is that early stages of global warming are already beginning to melt that ice. Greenland and Antarctica are losing billions of tons of ice each year, and depending on how far climate change goes, that ice will melt and that detailed, sophisticated, perfect climate record will melt away with it.

Q: In the absence of evidence like ice cores, will some record of humanity’s impact on the atmosphere survive?

JZ: Energy is so central to our lives, and a massive energy splurge has really taken off over the last 70 years. There’s no planetary analog for this kind of thing that we know of. Most of the stuff we burn for energy becomes carbon dioxide, of course, but the bits of carbon which are not burnt turn into fly ash, which are these tiny particles of carbon that — a bit like plastic — are almost completely indigestible to microbes. These tiny smoke particles land everywhere in the millions. So all around the world, there is a preserved smoke signal in the strata. It’s a really good marker for the Anthropocene.

SG: There’s all sorts of traces of climate change, but there’s this other kind of legacy of energy, and that is the infrastructure that we build to generate it and to transport it around the world. And each year we produce enough copper to wrap around the Earth more than 5000 times. So, we’re also leaving a legacy of the way that we shunt this energy around the Earth, as well as just the record of how it’s changing the climate.

Source link

Sachi Kitajima Mulkey grist.org