If we’re being honest, 2025 did not start out great. For basically the whole month of January, a series of wildfires raged across Los Angeles, killing hundreds (more on that number below). On the other side of the country, an Arctic blast brought historic snowfall and bitter cold deep into the South. Then Donald Trump took office for a second time on January 20 and immediately began to unravel the climate progress the United States had made under Joe Biden.

The rest of the year, which is on track to tie for the second hottest on record, was just as momentous, bringing all manner of climate events — some good, some bad. In a lot of ways, we’ll look back on 2025 as a critical moment, both for the environment and humanity. Here’s why.

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

A firestorm consumes Los Angeles

Starting on January 7, wildfires continued for weeks and burned 78 square miles across Los Angeles, driven by strong winds and fueled by extra-dry vegetation. (The conflagration had climate change’s fingerprints all over it.) The fires destroyed more than 16,000 structures and forced more than 180,000 people to evacuate. In part because the blazes were burning through extremely affluent neighborhoods, the economic damages are estimated to be between $76 billion and $131 billion. The fires were 1 of 14 billion-dollar disasters to hit the U.S. in the first half of 2025, according to the research group Climate Central. (In May, the Trump administration announced that the federal government would stop tracking billion-dollar disasters, an essential way to assess climate risks.)

Officially, the fires killed 30 people. But this year, researchers got a better idea of just how bad wildfire smoke is for public health, as it exacerbates conditions like asthma and cardiovascular disease. In August, scientists published a new estimate of the L.A. wildfire death toll that factored in fatalities caused by the resulting haze: 440, or even higher. The next month, other researchers estimated that wildfire smoke already kills 40,000 Americans each year, which could soar to 71,000 by 2050 if humanity’s carbon emissions remain high. The flames themselves, it seems, kill but a small fraction of the fire’s total victims.

Trump takes takes a hatchet to environmental regulations

Los Angeles was still burning when Donald Trump was sworn in for a second time and quickly began overhauling government agencies and axing environmental rules. The Trump administration’s deep cuts at the Environmental Protection Agency, for instance, could leave communities even more vulnerable to the threat of wildfire smoke. Later in the summer, Trump signed the so-called One Big Beautiful Bill into law, which among other things tore up the only climate plan the U.S. had. That killed the tax credits that consumers were using to electrify their homes and offset the cost of EVs, and destroyed the capital that Indigenous tribes were using to develop clean energy projects. (Also see Grist’s recent coverage of the weird ways that Trump has been changing the culture and language around energy and climate change.)

Extreme flooding is here to stay

Just as climate change is making wildfires worse, it’s actually making rainfall more catastrophic, too. That dynamic played out tragically on the Fourth of July weekend, when flash flooding struck central Texas, most devastatingly in Kerr County, killing at least 135 people. Part of the problem is that generally speaking, the warmer the atmosphere gets, the more moisture it can hold and eventually dump as rain. Making matters worse, the Gulf of Mexico has been exceptionally warm of late, which sent still more moisture into the atmosphere above Texas. (The same factors were fueling gnarly storms across the central and southern U.S. in the spring.) The resulting devastation is forcing a disaster-response reckoning not just in Kerr County but in similarly vulnerable communities across the U.S. Really, the world over is struggling to cope with extreme flooding: Storms and cyclones have killed more than 1,750 people in Asia since mid-November.

Data centers emerge as a major environmental threat

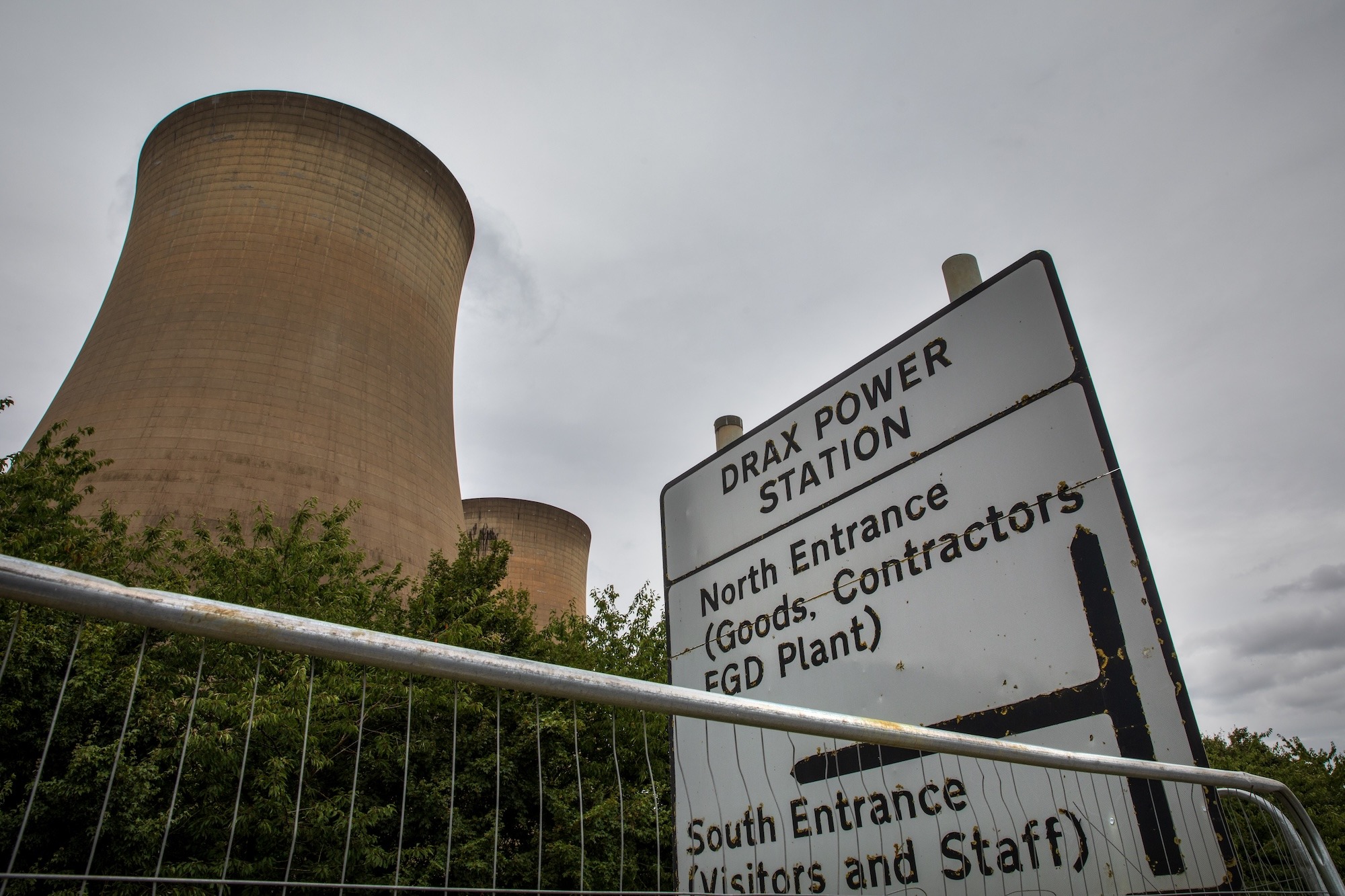

In 2025, another kind of human-made environmental disaster garnered growing scrutiny: data centers. In February, we reported on Georgia joining other states in extending the life of fossil-fuel power plants (which the Trump administration has also been forcing to stay open) to meet the tech industry’s extreme demand for electricity. The AI boom is hurting consumers, too: All that extra infrastructure is driving up electricity prices for households, especially in data-center hotspot states. The industry is such an environmental mess that Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, suggested this summer that we build data centers in space instead.

Data centers are creating a water crisis, too: Nationwide in 2023, the facilities used 17 billion gallons of water directly to cool equipment, but they required more than 10 times that amount indirectly because they use so much electricity that’s generated elsewhere with steam. Accordingly, researchers at Cornell University this year found that the industry can reduce both its water and electricity footprints by building data centers where there’s abundant wind or solar energy, like West Texas.

Earth crosses an ominous planetary boundary and tipping point

This year scientists hit us with a one-two punch of bad environmental news: The crossing of the first “tipping point” and the breaching of another “planetary boundary.” A tipping point is when an Earth system suddenly and often irreversibly changes into something dramatically different, while a planetary boundary is a threshold that keeps the planet’s environments hospitable to life. Think of it like driving down a road, where the tipping point is an imminent cliff and a planetary boundary is a big sign warning of the drop.

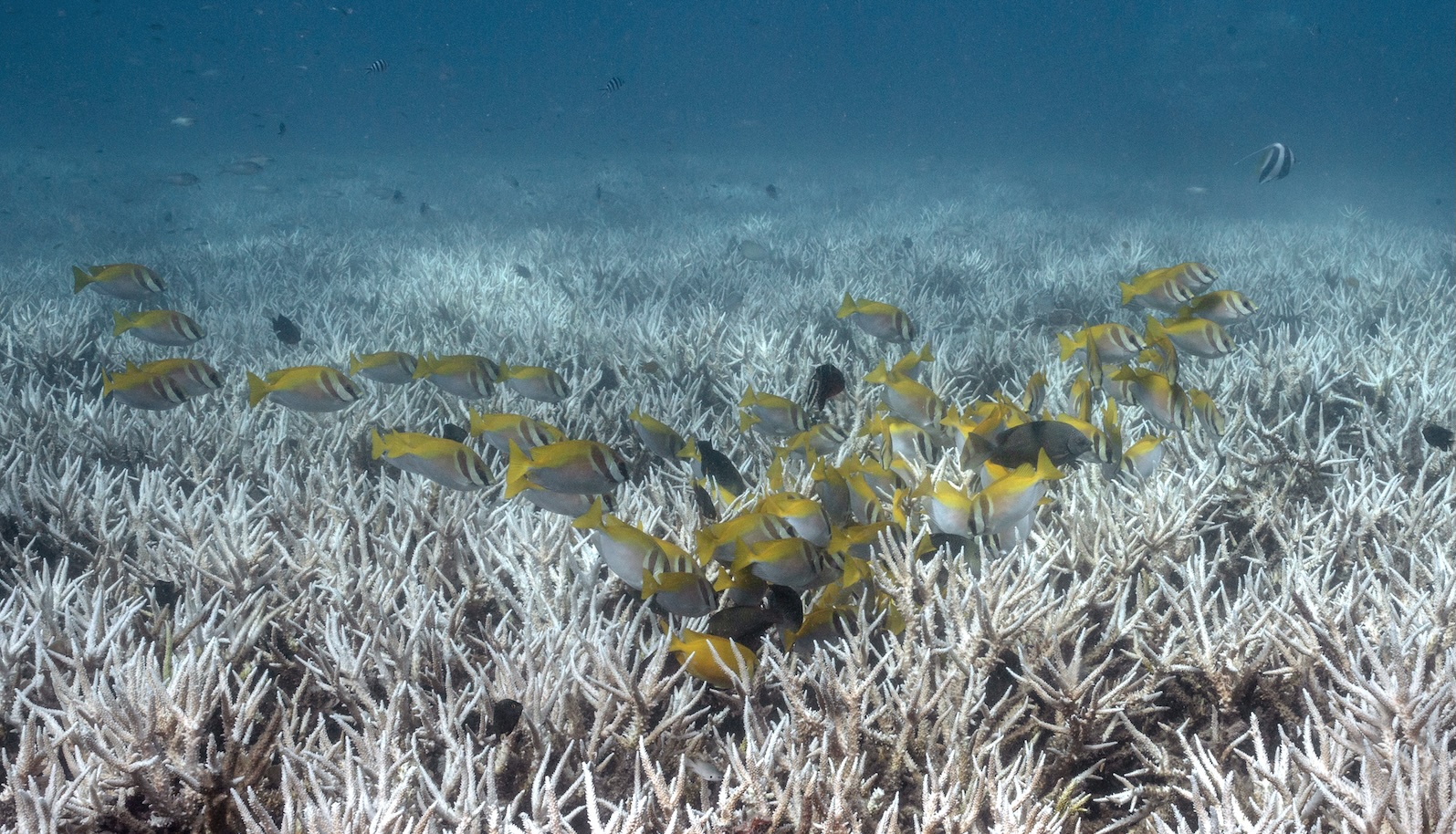

In September, scientists announced that the seventh of nine boundaries had been crossed, this time the steady acidification of the oceans. (A quarter of humanity’s CO2 emissions have been absorbed by seawater, which creates carbonic acid.) That acidification is interfering with the ability of many organisms, like corals, mollusks, and crustaceans, to build their shells.

And speaking of corals, less than a month later, another team of researchers announced that the precipitous decline of reef ecosystems has pushed the planet to its first major tipping point. In the last 50 years, half of the world’s live coral cover has disappeared, as acidification pairs with rising ocean temperatures. All that stress causes corals to release the symbiotic algae that provide them energy, leading to coral bleaching. Even though corals are tipping, scientists are still breeding them in labs, hopefully finding varieties that can better stand the heat.

Countries cop-out at COP

You’d think that with such dire news about tipping points and planetary boundaries coming out, the world would get more ambitious about lowering its emissions. But 10 years after the Paris Agreement — which set out to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, or in an ideal world, 1.5 degrees — countries at the United Nations’ annual COP30 climate conference in November failed to come to an agreement on winding down fossil fuels. So we’re on track to get between 2.3 and 2.8 degrees of catastrophic warming by the end of this century, according to the U.N.’s own math. Every fraction of a degree means ever more severe effects of climate change — melting ice, sea level rise, extreme heat — and the further we go past 1.5 degrees, the more carbon we’ll have to remove from the atmosphere to bring temperatures back down to a safe level.

Hurricane season ends without a single US landfall

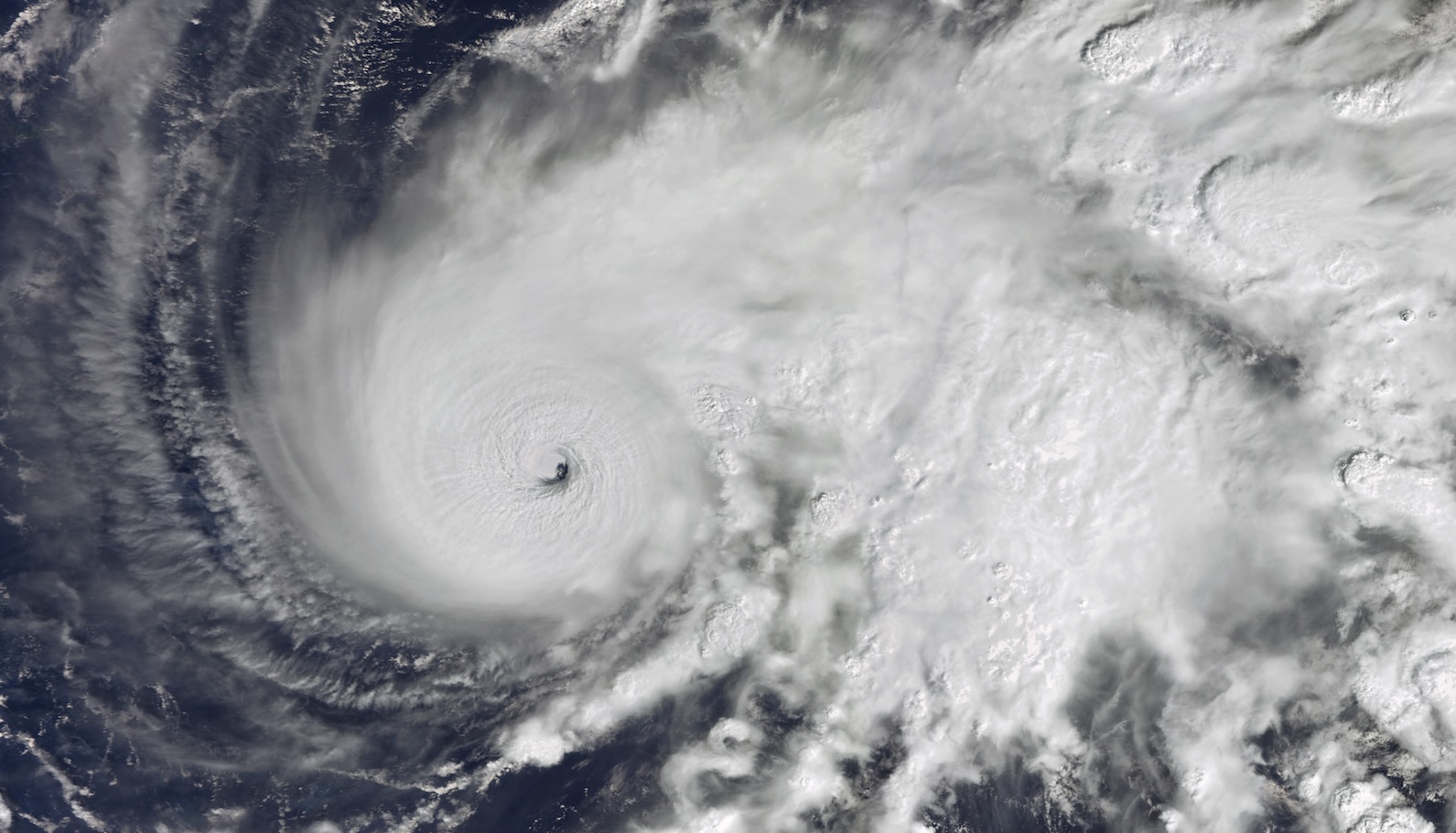

This spring, forecasters were looking at high ocean temperatures in the Atlantic — the fuel for hurricanes — and predicting an above-average season with around 10 named storms. But as the summer stretched on, the hurricanes that seemed headed for the mainland U.S. instead turned back out to sea. Hurricane season ended on November 30 without a single hurricane making landfall in the country for the first time in a decade, thanks to some atmospheric quirks above the Southeast.

The Caribbean, though, did not fare so well this year. At the end of October, Hurricane Melissa — supercharged by climate change — ravaged Jamaica, Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. Because of extra-hot ocean waters, the storm’s maximum sustained wind speeds doubled from 70 mph to 140 mph in just 18 hours. So while it’s unusual for the U.S. to escape landfall for a whole season, tropical cyclones will only get worse from here as ocean temperatures climb: This was only the second year in recorded history to have spawned three or more Category 5 hurricanes.

Climate action has become unstoppable in many ways

Heading into 2026, it’s easy to look at all this and say, “Well, we’re borked.” Yes, the environment is buckling under the increasingly heavy burden of climate change. And yes, the Trump administration will continue its war on climate action. But unstoppable changes — the good kind — are already in motion that will help improve public health and reduce emissions, no matter what the federal government decrees.

For one, those environmental tipping points have positive counterparts that are now unfolding, thanks to local incentives and national policies elsewhere. The market share for new electric vehicles in Oslo, Norway, for instance, exploded from 13.6 percent to 95.8 percent in a decade, according to a report released in October. Solar panels have gotten so cheap that it’s now more economical to deploy renewables than to build more fossil fuel infrastructure. Accordingly, renewables are growing like crazy in the U.S. and beyond, with a new report finding that wind and solar are more than meeting the global rise in demand for electricity. Indeed, in the first half of 2025, renewables generated more electricity around the world than coal for the first time. The leaders of Africa’s growing economies, meanwhile, plotted a bold strategy this year to become a continent of climate solutions.

And keep in mind that in the absence of federal U.S. action on climate change, states and cities have stepped up to fill the void and have even increased their ambitions this year: They set their own emissions-reduction targets, regulated their own utilities, bolstered public transportation, drafted energy-efficient building codes — the list goes on and on. Yes, 2025 was an ominous year, both environmentally and politically, but that doesn’t mean that all is lost in 2026.

Source link

Matt Simon grist.org