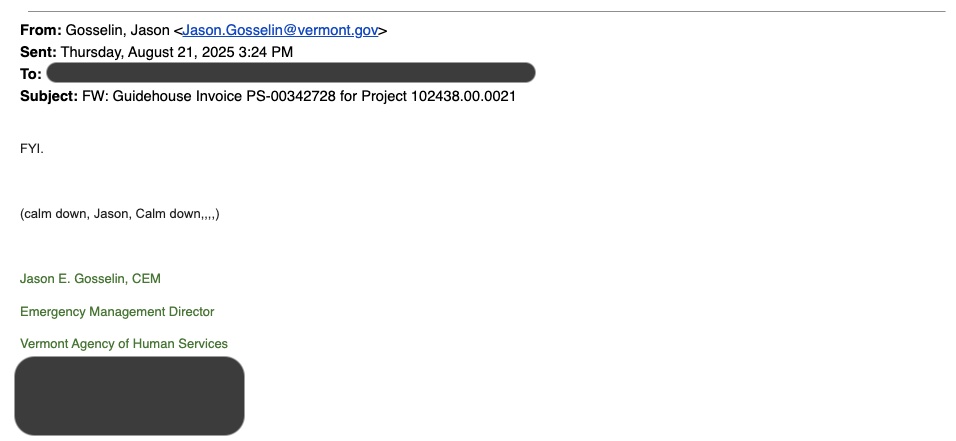

On the afternoon of August 21, Jason Gosselin raised the alarm: the flood recovery project he managed was running out of money faster than he had anticipated. One email he sent his colleagues ended with an anxious parenthetical: ”(calm down, Jason, Calm down,,,).”

In July 2024, Vermont was hit by 100-year flooding for the second summer in a row. Among the aid that the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, approved was a $2.9 million grant to hire an 11-person disaster case management team to help victims navigate their FEMA applications, find other available resources, and rebuild their homes. The money was supposed to last two years, but was on pace to be gone far sooner. The morning after his first email, Gosselin, who is the emergency management director at the Vermont Agency of Human Services, sent another message detailing the likely source of the unexpected financial drain. The corporate contractor Vermont used to hire the team, he calculated, was actually billing nearly half of the budget for its own staff.

“We cannot / will not be able to support this,” concluded Gosselin. According to documents obtained by Grist, Gosselin was right — and the problem was even worse than he seemed to realize.

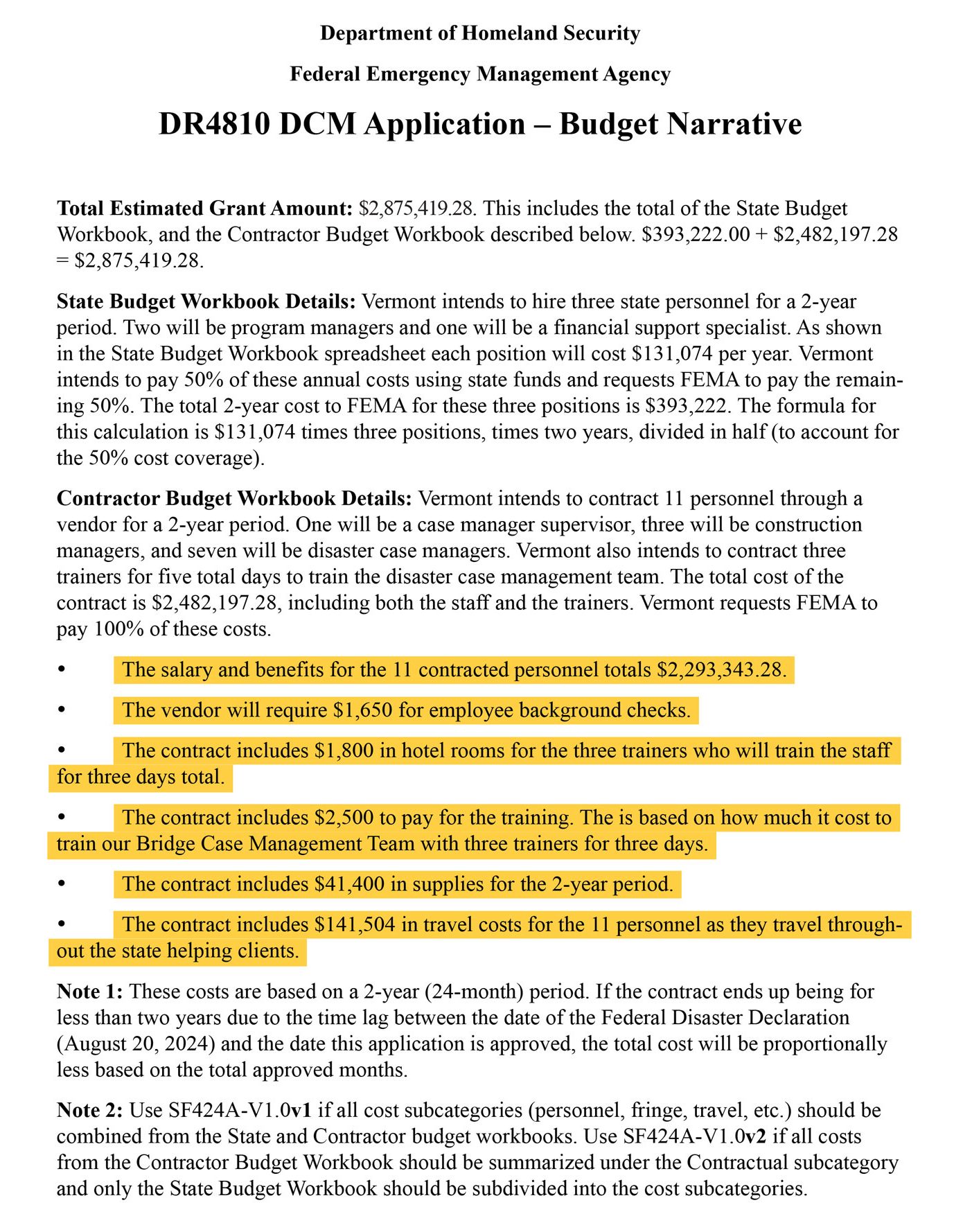

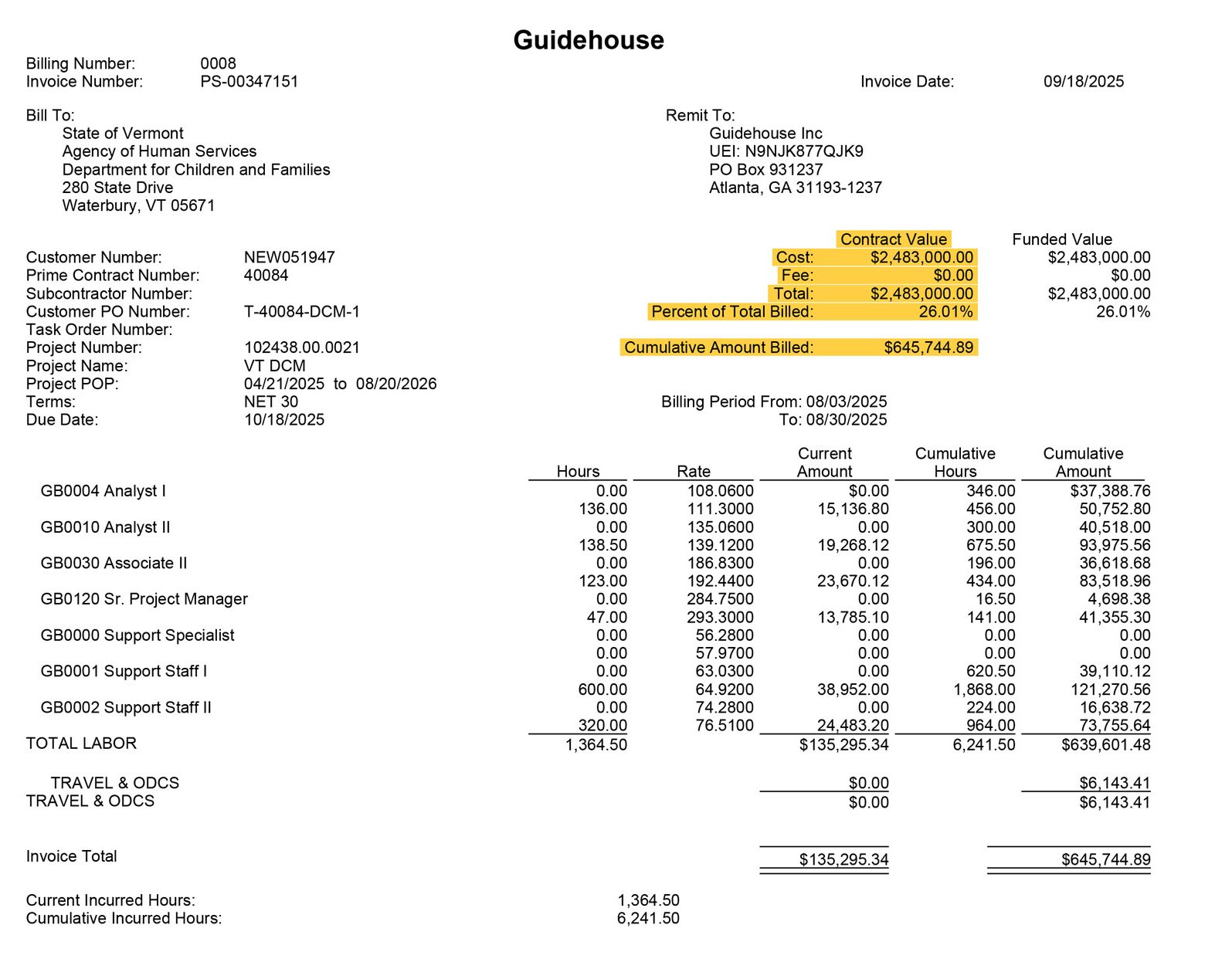

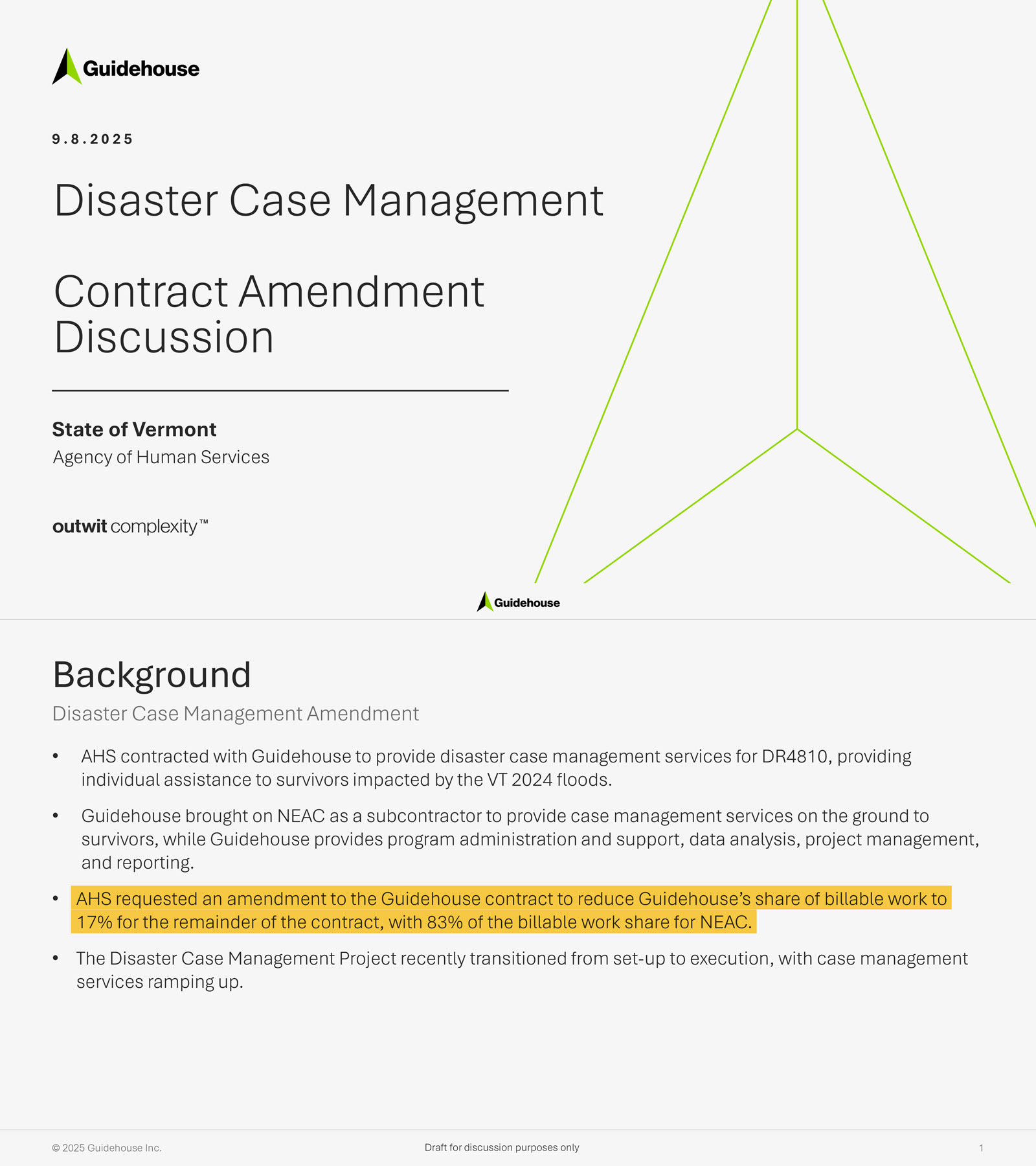

Records show the state kept about $400,000 for hiring its own administrative staff. The rest — $2.5 million — was allocated to Guidehouse, a multinational consulting company, to hire the frontline workers. But Guidehouse only subcontracted seven people, instead of 11, for $1.1 million. That left more than a million dollars that the company could use toward its own services.

“There is a huge need in the state,” said Prem Linskey, the case management supervisor at a local Vermont aid group, the Recovery After Floods Team. The amount of work is often untenable, with so many people that need help. “The state’s case management plan could have been much more effective if they had hired more people.”

A state official told Grist the program cost more than expected to get started, and it has since reined in costs. But although Vermont’s grant is relatively small compared to the billions of dollars that FEMA doles out each year, experts say the poor state oversight, vague contract terms, and high-priced consultants that accompanied it are unfortunately common. Cracks like these are only set to widen as climate change fuels extreme weather and President Donald Trump’s administration pushes more response and recovery responsibilities onto states that, too often, lack experience, expertise, and capacity. And, if a federal grant is mishandled, it’s usually not FEMA or the contractor holding the bill, but the state — and the stakes can be enormous.

Kayla Bartkowski/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Late last month, FEMA sent Gosselin and his team an informal yet stern email warning what would happen if they didn’t correct course. “Deficiencies can result in a range of consequences, including corrective action plans, formal audit findings, and heaven forbid, clawbacks,” wrote Penelope Doherty, who works with the agency’s regional office. “Any of these can affect a state’s ability to receive federal funding of any kind, not just from FEMA.”

Last year’s flooding was the result of two separate severe storms. On July 10, up to 7 inches of rain dropped on parts of Vermont in a matter of hours. On July 30, with the soil still soaked and rivers high, the Northeast Kingdom region got upwards of 8.4 inches. The torrential rains killed two people, ripped apart homes, and caused billions of dollars worth of damage. Within weeks, FEMA approved an official disaster declaration and Vermont stood up a temporary “bridge” team of case managers that were largely reassigned from other state positions. That program was set to wind down at the end of the year and there were still dozens of active cases. So, two days before Christmas, the state submitted a grant application to FEMA aimed at addressing the “unmet needs” of Vermonters.

In its application, the state estimated that 134 flood survivors still needed so-called “disaster case management,” or extra assistance developing and implementing a recovery plan. Some $2.5 million of the grant would “be specifically for” seven disaster case managers, or DCMs, three construction managers and a supervisor. There are no other positions mentioned in the state’s application or included in its budget.

In February, FEMA approved Vermont’s $2.9 million “Disaster Case Management Program.” The state in-turn hired the consulting firm Guidehouse, which used to be the public sector arm of PwC (formerly Price Waterhouse Coopers). Through various mergers and acquisitions, it’s since grown into a $7 billion company now owned by the private equity giant Bain Capital.

Vermont had been working with Guidehouse since 2020, when the global COVID-19 pandemic took hold. The state competitively bid and signed a five-year master contract with Guidehouse that let any of its agencies issue a “task order” for services from the company, without having to seek bids again. While the bulk of the work seems to have stayed in the COVID realm, the governor told reporters in 2024 that the company was also helping to “augment” the state’s flood response effort.

This April, Vermont’s secretary of human services, chief recovery officer, and an assistant attorney general signed a $2,483,000 task order with Guidehouse to help with the FEMA disaster management grant. It names Gosselin as a primary contact and includes language such as, “The Contractor shall support the State in administering its DCM Program” and “Provide implementation and strategic advisory assistance to the State.” It doesn’t have the specific staffing requirements.

With its orders in hand, Guidehouse then did its own subcontracting for the frontline workers. It turned to the New England Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church, or NEAC, which had been involved with previous flood recovery efforts in Vermont. But that subcontract proved to be significantly narrower than what was in the FEMA agreement. NEAC would provide only four case managers, not seven, and just two construction coordinators, not three. It also pays the organization just $1,098,875.00 to get the job done, including a travel budget. That’s less than half what Guidehouse got from the state, and what FEMA awarded for the work. It’s unclear exactly what the company’s plan was for the other $1.4 million, but the NEAC agreement lists six Guidehouse employees working on the project — a nearly 1:1 ratio with frontline workers.

All federal grants involve some level of administrative costs, explained MaryAnn Tierney, a former FEMA regional administrator and acting No. 2 at the agency. But when money that is meant to go to services goes to overhead, she said, “that’s not acceptable.”

Another former FEMA official, who asked not to be named publicly because they are now a consultant that works with the federal government, said the agency would start to get upset when such expenses reached 20 percent. “It doesn’t necessarily mean that I would have thought it was fraudulent,” they said. “I would just be grumpy because it’s a waste of money.”

Vermont’s case is a “classic” example of what happens when a state or municipality writes a vague contract, said Craig Fugate, who was the FEMA administrator from 2009 to 2017. He explained that any contract should provide clear and measurable deliverables, with penalties for not performing.

Without a strong agreement, a consultant can largely dictate their own boundaries. “You see a lot of money getting spent on process. More meetings, more reviews,” said Fugate. While no one technically violates the contract, “it doesn’t seem that much work is getting done, and you end up with a lot of billable hours.”

Kayla Bartkowski/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

By the time Gosselin did his August accounting, Guidehouse had already billed 4,877 hours of time — worth over half a million dollars. The Guidehouse report to the state that his math was based on shows 48 percent of that money going directly toward Guidehouse staff. The consulting firm also added overhead to the NEAC staff’s hourly rates, meaning that an even greater share went to the company.

According to two people involved in the grant, it was common for multiple Guidehouse employees to attend meetings, and it was often unclear why they were necessary. “It muddied the waters a little bit,” said one of them. Both mentioned that the role of Lina Hashem, a director at Guidehouse, was especially confusing and redundant, especially given her billing rate: $293 per hour.

Before becoming FEMA administrator, Fugate spent decades as an emergency manager at state and local levels. The role of contractors has expanded dramatically, he said. Where companies used to be selling mostly goods or products — say generators, or computer systems — many are now offering services, such as consulting.

Outside companies can be a useful force multiplier in the wake of a disaster, and offer expertise that states may not have. “For state governments, you’re never going to have enough people to handle Hurricane Katrina,” he said. “But you always have to keep the idea that we’re not turning over running the response or the recovery to a vendor.”

FEMA spends tens of billions of dollars every year on disaster recovery, but there is also additional funding available across the federal government: more than two-dozen other agencies run nearly 100 different response or recovery programs.

There have been several high profile instances of either contractor abuse or state mismanagement. Following a 2014 tornado in Louisville, Mississippi, the inspector general overseeing FEMA recommended that the agency clawback $25 million because the city didn’t follow proper procurement procedures. Last year, the consulting firm Horne paid a $1.2 million fine for improper billing in the wake of extreme rainfall in West Virginia in 2016. Horne now holds a controversial $81 million contract to help North Carolina recover from Hurricane Helene.

Guidehouse’s work has also come under scrutiny. Last year, it paid a $7.6 million fine for a data breach tied to the company’s work administering New York’s rental assistance program during the pandemic. Still, it’s become a major player in the disaster space nationwide. It won the $135 million contract to revamp the National Flood Insurance Program and a $38 million one to do identity verification for FEMA. It also acquired part of a company that worked with New Jersey in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, and Florida after Hurricane Irma.

Vermont’s vendor payment portal shows $41 million to dollars in payments to Guidehouse since 2020, and not all the state’s experiences with the company have been bad. It was instrumental in helping Vermont navigate both the COVID-19 pandemic and 2023 flooding, said Ben Rose, who retired as Vermont Emergency Management’s recovery and mitigation section chief at the end of 2024.

“It’s really hard to hire people through the state system,” he said. “You can be more nimble by hiring consultants when you need help.”

That said, Rose was cognizant that Guidehouse was a for-profit company and said keeping tabs on its scope of work and spending was important. “They would sometimes say ‘Hey, we’ll make it easy for you, let us show you a draft task order,” he recalled. Rose would then take off things that he didn’t need. “It was a healthy back and forth.”

In his August emails, Gosselin appears surprised by how much of the grant money was going to Guidehouse. And when FEMA started asking for more details, the state dragged its feet in explaining what happened. Initially, Dougherty wrote in her warning note, the state had “revealed a decision to reduce service delivery staff,” which would have been acceptable as long as the budget was reduced as well. But after more than two months, and three draft proposals, she noted that there still wasn’t a formal update to the original plan.

“We have been requesting this articulation since mid-July,” wrote Dougherty, in late September. “[It] really must be finalized to avoid risking corrective actions.”

The state continues to work with FEMA on an updated plan, said Douglas Farnham, Vermont’s Chief Recovery Officer. But he defended the state’s use of Guidehouse, which he said was a natural fit for the project because it already worked with the state and was best positioned to rapidly stand up this program, too.

“They’re not the cheapest partner to work with but they have great expertise,” said Farnham, adding that moving quickly adds expense as well. He blamed the high initial billing ratios — with nearly half going to Guidehouse — on startup costs for the project.

“Ideally, you wouldn’t see it bump that high,” he said, but after the state reviewed the expenses, they found them to be reasonable. “At the end of the day, we believe the costs were appropriate. They were necessary to build the program and we’ll work it out with FEMA.”

FEMA could not be reached for comment, due to the current government shutdown.

Farnham said that the state has since set a new target of 17 percent for Guidehouse’s share of billable work, with the rest going toward program delivery. “It definitely stops the major bleed,” said one person familiar with the changes, though they still question why Guidehouse has to remain involved at all. And because the changes come months into the project and more than a year after the flooding, some say much of the harm has already been done.

For one, Vermont has already paid Guidehouse hundreds of thousands dollars that FEMA has yet to reimburse. If the agency doesn’t do that, Farnham said the money would come out of the state’s reserve fund for federal denials. Timing was also a problem. The FEMA-funded case management program wasn’t approved until seven months after the disaster declaration. Farnham, while grateful for the money, said that was a result of FEMA’s “very long and complicated” application process.

The state also hired fewer workers than planned because there weren’t as many cases as expected, Farnham said. The benefit of a contractor, he said, is that the number of workers can be adjusted up or down. But the company’s own October 1 report listed a “medium” risk that the caseload “may exceed budgeted project team capacity.”

Farnham doesn’t think that will happen, and would rather extend the length of the program to help handle cases that come up later. FEMA has not approved that extension but in her September email, Dougherty did tell the state to “be aware of the inherent conflict in simultaneously saying you’re behind/need more time and saying outreach results indicate you can reduce the work force/work pace.”

Guidehouse’s agreement with Vermont only covered disasters that happened through June 2025, and the state has chosen another company for its next master contract. Farnham declined to explain why, and Guidehouse declined to comment for this story, as did NEAC. Gosselin didn’t respond to multiple interview requests, or a list of written questions. But long-term recovery groups say that, even when the state did finally get involved in case management, it failed to coordinate well with those already on the ground. “They confused everybody,” said Meghan Wayland, president of the Kingdom United Resilience & Recovery Effort. “They called all of the people in our neighborhood. It creates chaos and we have to go to clean up their messes.”

Wayland and Linskey, from the Recovery After Floods Team, say that better collaboration with organizations like theirs could have meant more work for the FEMA-funded folks, too. For example, the NEAC team could have taken on particularly difficult cases or focused on areas of the state where the local capacity isn’t as robust. “They could have designed a program that would have benefited Vermonters and not compromised the efforts that are under way,” said Wayland. “That would have been a really lovely thing for them to do.”

Kayla Bartkowski/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Multiple people pointed to Gosselin as a major source of the state’s issues. “He doesn’t have the appropriate skill set for the thing he’s been put in charge of,” said Wayland. Another person said, “we all keep trying to clean up [his] mess but it’s just so pervasive.” But Gosselin notably wasn’t the signatory on the Guidehouse task order or the FEMA application, which were ostensibly reviewed by officials higher up in government. That includes Farnham, who praised Gosselin for flagging Guidehouse’s invoices for review and said “everything that I worked with him on this, I believe he took the right course of action.”

For now, FEMA’s review of Vermont’s spending is still underway. But the lesson may already be clear: As floods multiply and dollars surge, America’s recovery system is only as strong as the contracts holding it together. And, currently, states could be a weak point in that chain.

“By shoving responsibilities from the federal level onto the state’s shoulders, it is creating a market for private contractors,” said one FEMA employee, who asked to remain anonymous because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly. “They’re sitting ducks.”

Source link

Tik Root grist.org