The work reveals which human-driven activities are the main drivers

Adapted from a press release produced by the University of California, Irvine.

- The sinking is placing more than 236 million people at increased flooding risk in the near future.

- The findings could help communities residing in deltas better prioritize immediate local interventions alongside climate adaptation efforts.

The world’s deltas are home to hundreds of millions of people—but there’s a problem: they’re sinking. New research published in Nature by scientists from the University of California, Irvine, Columbia University and other institutions documents the rate of elevation loss in the world’s deltas and finds that human activities are the primary reason for it.

“This careful study is the first comprehensive quantification of the role that humans play in delta subsidence, and the results are eye-opening,” says coauthor James L. Davis, a geodesist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, which is part of the Columbia Climate School.

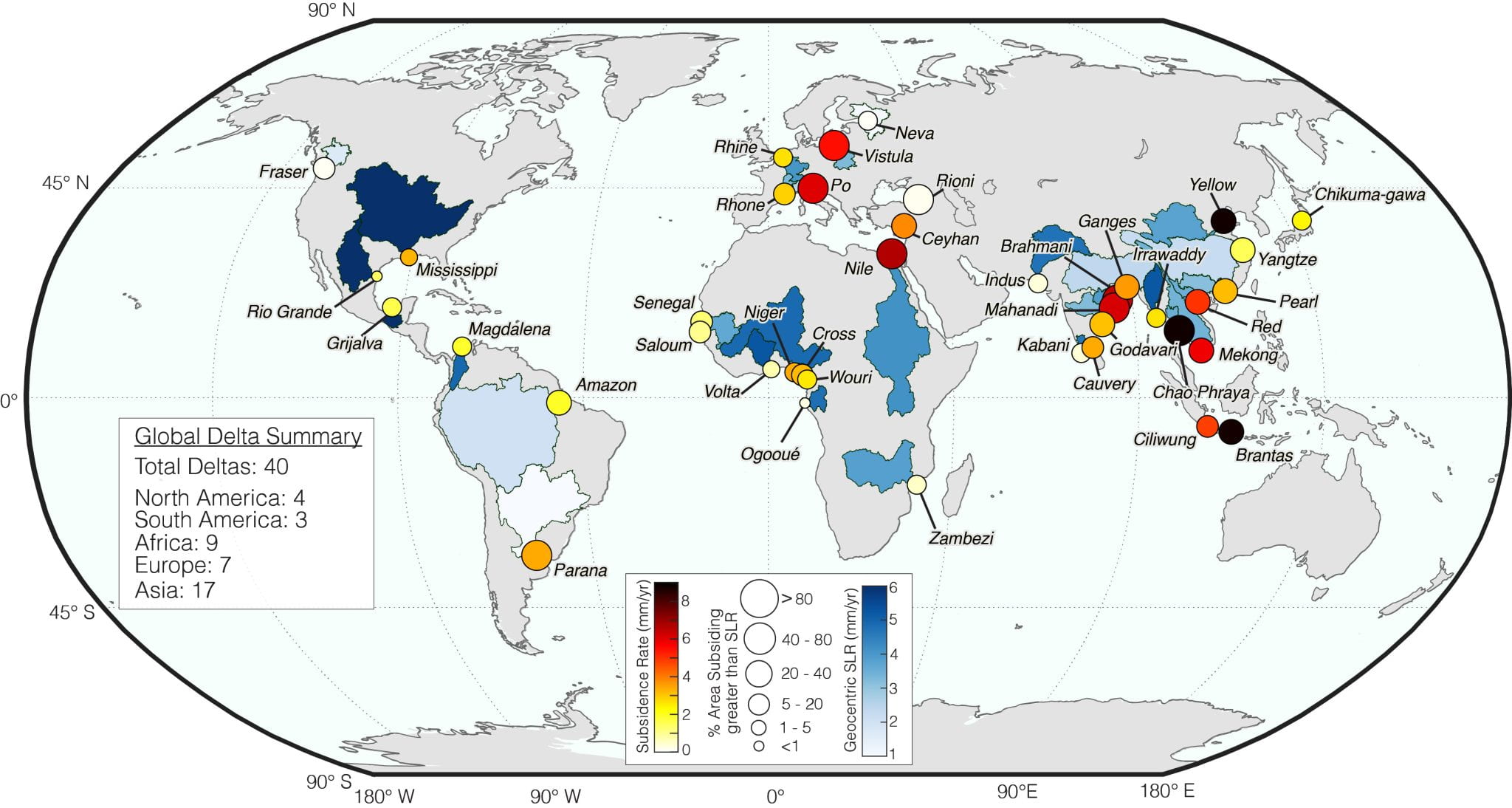

The new study provides the first delta-wide, high-resolution subsidence observations across 40 major river delta systems, revealing not just where land is sinking, but quantifying how much.

“We also quantified the relative contributions of specific human drivers: groundwater extraction, sediment starvation and urbanization across these deltas, which allows us to identify the dominant drivers of the sinking,” says UC Irvine’s Leonard Ohenhen, lead author of the study. Ohenhen was previously a Lamont postdoctoral fellow.

The team found that, across deltas, land is sinking at an average rate ranging from less than one millimeter per year in deltas like the Fraser River Delta in Canada, to more than one centimeter per year in China’s Yellow River Delta, with many areas sinking more than double the rate of global sea-level rise.

The lack of high-resolution elevation change measurements along coasts and deltas around the world has long hindered efforts to distinguish the severity of land subsidence and sea-level rise.

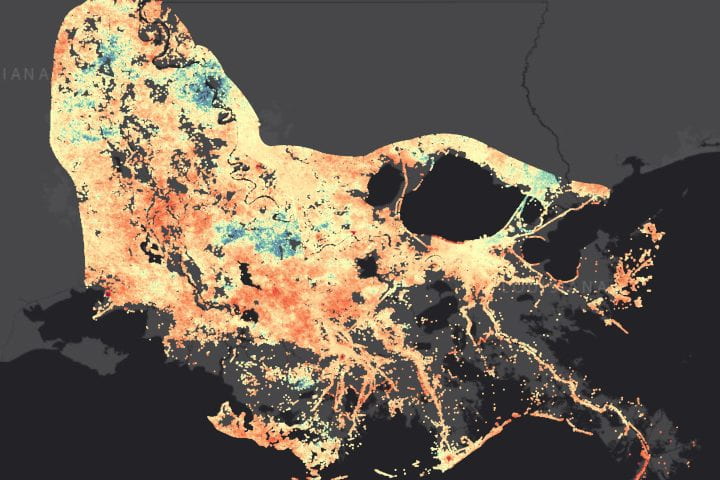

Using satellite radar data, the research team measured land elevation change across 40 deltas. The analysis revealed that in 35 percent of them, extraction of groundwater by humans is the main driver of land subsidence.

“The dominance of subsidence over sea-level rise was more pervasive than anticipated, and in every delta we monitored, at least some portion is sinking faster than the sea surface is rising,” says Ohenhen.

In the United States, for example, the Mississippi River Delta has a long-documented history of subsidence, and the new analysis confirms that this trend remains pronounced.

“The Mississippi Delta is sinking at an average rate of 3.3 millimeters per year, compared with the regional Gulf Coast sea-level rise of 7.3 millimeters per year—though substantial areas are subsiding faster than this local sea level rise, in some areas more than 89 millimeters (3.5 inches) per decade,” says Ohenhen. “These patterns reinforce ongoing land-loss concerns in coastal Louisiana from both the land and the seas.”

While land subsidence often dominates present-day exposure in most deltas, climate-driven sea-level rise remains a fundamental long-term threat. Melting polar ice and warming ocean temperatures are currently causing global mean sea level to rise by four millimeters every year—a rate that’s expected to accelerate throughout the coming century.

“Deltas are really ‘stuck in the middle’ when it comes to climate risk,” says Lamont geophysicist Austin Chadwick, who is an assistant professor at the Columbia Climate School and one of the study’s coauthors. “Global sea levels are rising, rivers threaten to pour over their banks during large storms, and to make matters worse, the land itself is sinking.”

Ohenhen explains how the findings should help populations inhabiting deltaic regions better prioritize mitigation and choose adaptation strategies.

“These results give delta communities a clearer picture of an additional threat, which can cause increased flood exposure, and that clarity on the hazard facing them matters,” Ohenhen says. “If the land is sinking faster than the sea is rising, then investments in groundwater management, sediment restoration and resilient infrastructure become the most immediate and effective ways to reduce exposure.”

Collaborators include Manoochehr Shirzaei and Susanna Werth of Virginia Tech, Robert Nicholls of the University of East Anglia and University of Southampton in England, Philip Minderhoud of Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands and Julius Oelsmann of Tulane University. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation, NASA, and the United States Department of Defense.

Source link

Columbia Climate School news.climate.columbia.edu