3.1. Water Quality Analysis

A total of eight storm events (i.e., twenty-four (24) water samples were collected, one during each stage) were analyzed, of which 37.5% were taken in 2020 during the imposition of the COVID-19 restrictions, while the rest were collected in 2021 (25%) and 2022 (37.5%). Even though the number of storms was high enough to develop the analyses, the authors recommend including automatic sampling, if possible, to minimize errors.

All water quality parameters (i.e., pH and conductivity), along with streamflow, ADD, and the total number of vehicles, are detailed in

Table 2. Stormwater conductivity ranged from 381 to 1266 μmhos, while ADD was documented to be between 1 and 15 days. Moreover, the streamflow’s pH ranged between 4.6 and 8.6, though typical pH values in surface waters (not stormwater) in Denver are generally basic (between 8.5 and 9.2) [

47]. However, most pH values in LG fell within the acceptable range (6.5 to 9) for Colorado Surface Water Quality Standards [

16]. Nevertheless, April flows showed acidic conditions (pH between 4 and 5), which could either be due to the nitric acid naturally contained in precipitation for a particular storm [

48] or possibly traffic-related pollution [

49]. Acidic water has a negative effect on aquatic ecosystems, leading to a decrease in the number of plankton and benthic invertebrate species and the reproductive failure of acid-sensitive species of amphibians (e.g., leopard frogs and salamanders) [

50], while also altering chemical conditions such that they become toxic to fish and other aquatic animals [

51]. Additionally, drinking acidic water might make a person sick, damage certain tissues, and may even result in fatality [

52]. Therefore, the regular monitoring of pH is highly recommended for LG and Denver’s urban watersheds with streams. Cement porous pavements (CPP) may be used to increase the pH in stormwater in Denver [

53], though other methods could be tested as well; for example, Kazemi and Hill [

54] used permeable basalt-based aggregates to increase the pH in stormwater near Athelstone, South Australia.

The MCLs set by the EPA for drinking water are often used as a metric of anthropogenic impacts on natural aquatic systems (e.g., [

45]). Based on the literature [

8,

11,

55,

56], all selected metals (Fe, Mn, Pb, Zn, Cu, Ba, Ni, Cr) except for Si are traffic-related and thus are relevant for this analysis. However,

Table 3 and

Figure 2 show that Ni, Cr, and Zn generally have very low concentrations, often approaching the detection limit or perhaps representing background concentrations. Cu and Ba display concentrations well above the detection limit but always an order of magnitude below the MCL. Thus, our analysis of metal pollution will primarily focus on Fe, Mn, and Pb. However, the analysis of Cu, Ba, and Zn can be useful for some analyses (i.e., assessing whether traffic is a primary source of pollution) because they have concentrations that vary substantially between storms and that are well above the analytical detection limit. This approach is supported by Wang et al. [

38] and Müller et al. [

57], who concluded that metals such as Ba, Cu, Fe, Mn, Pb, and Zn can originate from vehicles. Before analyzing the potential traffic source, however, a traditional water quality analysis is provided.

Fe and Mn exceeded regulated standards in every sampled storm event, showing high variability within the three-year sampling period, with maximum values of 3.2 and 0.6 mg/L, respectively. A Fe concentration of 3.2 mg/L in stormwater is considered highly polluted, because the MCL for this metal is only 0.3 mg/L. Similarly, Pb exceeded legal concentration limits on five occasions (three events), peaking at nearly 0.027 mg/L, which is higher than the regulated limit of 0.015 (see

Figure 2). These results agree with the findings by Li et al. [

58], who investigated Mn, Pb, and Fe in Beijing (China) and reported that these metals also exceeded local water quality standards.

Previous studies developed in different cities around the world, in contrast to what was obtained in this investigation, are listed in

Table 4. The mean Fe, Mn, Pb, and Zn concentrations in Denver are 3.590 mg/L, 0.268 mg/L, 0.056 mg/L, and 0.761 mg/L, respectively. Generally speaking, the mean concentrations determined in this study are greater than the concentrations obtained in Sweden [

59] and Japan [

60], likely due to a high reliance on private vehicles instead of public transportation or the different regulatory framework governing traffic vehicle emissions between the US and these countries. However, climate might play a crucial role, as Stockholm (Sweden) and Shiga (Japan) receive around 550 [

61] and 1590 mm [

62] of annual precipitation, respectively, which is higher than semiarid Denver, which receives only around 363 mm/year, and a significant portion of it falls as snow during winter months [

34]. Experiencing rainfall more often in a given city means streets being cleaned regularly, resulting in cleaner stormwater.

In contrast, the pollutant concentrations obtained in this study are lower than those reported in Australia [

63], United States (Texas [

64] and California [

65]), China [

56], Peru [

66], and France [

11] (see

Table 4). Many factors can explain these differences, but considering the city of Arequipa in Peru as an example, with highly polluted stormwater samples [

66], a possible explanation is the difference in climate, as this South American city receives less than 144 mm/year of rainfall [

67], meaning more pollutants accumulating on streets and fewer washing events. Similarly, the types of vehicles that circulate in Arequipa are characterized as being old and in poor repair [

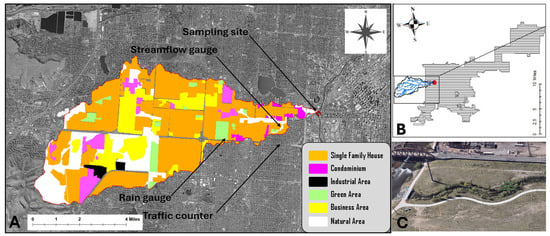

66], which can lead to greater leakage of contaminants. Finally, the land use characteristics in the Peruvian study site are composed mostly of cement, with a complete absence of green areas, located in a part of the city characterized by heavy traffic flow (downtown Arequipa). In contrast, LG has 363 mm/year of precipitation [

34], with relatively newer cars or better maintained cars due to stricter environmental regulations, lower vehicular traffic intensity, and green and natural areas account for 4% and 18% of the area, respectively.

Table 4.

Metal concentrations in urban stormwater from the literature (mg/L).

Table 4.

Metal concentrations in urban stormwater from the literature (mg/L).

| Reference | City | Fe | Mn | Pb | Zn |

|---|

| This study | Denver, CO, USA | 1.89 | 0.29 | 0.015 | 0.111 |

| [59] | Stockholm, Sweden | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00014 | 0.100 |

| [60] | Shiga, Japan | 1.57 | 0.05 | 0.014 | 0.502 |

| [56] | Chaoyang, China | | | 0.100 | 1.000 |

| [64] | Austin, TX, USA | 3.54 | | 0.099 | 0.237 |

| [63] | Nerang, Australia | 5.50 | 0.08 | 0.030 | 0.200 |

| [66] | Arequipa, Peru | 9.00 | 0.90 | 0.011 | 5.000 |

| [11] | Paris, France | | | 0.025 | 0.260 |

| [68] | Mount Rainier, MD, USA | | | 0.190 | 0.001 |

| [65] | Multiple cities in CA, USA | | | 0.080 | 0.203 |

| Average | | 3.590 | 0.268 | 0.056 | 0.761 |

3.2. Pollutant Mass Loads: General Analysis

Mass load distributions, using flow and concentration data in

Table 2 and

Table 3, are illustrated in

Figure 3. Fe, Mn, and Pb (the pollutants that were found at levels above the EPA standards) showed a wide range of loading rates, with average loading rates of 2699, 464, and 19 mg/s, respectively. Si is not generally considered a traffic pollutant, as previously mentioned, and its high concentrations are expected based on the typically high concentrations of silica in Denver-area sediments [

40].

Moreover, based on our sampled storm events and considering a documented average summer stormflow duration of 126 min for the three years under study (all based on

Table 3, excluding the first unusually longer event), and an average of 22 summer storm events (May through August between 2020 and 2022) per year in LG (having a drainage area of 3354 ha), the watershed is estimated to have 0.4489, 0.0772, and 0.0032 MT, or 1.34 × 10

−4, 2.3 × 10

−5, and 1.0 × 10

−6 MT/ha of Fe, Mn, and Pb, respectively, being released directly into the South Platte River from the watershed every year.

Huber and Helmreich [

37] estimated the traffic-related emissions in Germany for seven different sources (tire wear, brake lining wear, roadway abrasion, weights for tire balance, guardrails, lampposts/signs, and de-icing salts), and determined a level of 0.003 MT/year-ha for Pb. Their results were much higher than those obtained in this study, most likely because the authors estimated total annual pollution considering all highways nationwide. In Cranston (USA), Hoffman et al. [

69] reported levels of 0.28, 0.054, and 0.14 Mg/year-ha for Fe, Mn, and Pb, respectively, demonstrating higher annual pollution levels than those obtained in this study, most likely because the authors sampled stormwater near a busy highway, even though their drainage area was only 44 ha. Moreover, the previously mentioned study by Martínez et al. [

66] in Arequipa (Peru) also reported that Fe, Mn, and Pb concentrations (and loads) were above those set out by local environmental regulations, though the authors did not provide enough information to estimate annual pollution loads.

3.3. General Relationships Between Water Quality Variables

Using the data in

Table 3, a correlation matrix was created for metal concentrations and metal mass load considering all data (top in

Figure 4), and we assessed their correlation with the number of vehicles during each of the first 10 days of antecedent vehicular activity (bottom in

Figure 4) to better understand the potential causal relationships. High, positive Pearson correlation coefficients were documented among all pollutants (i.e., the pollutants were all correlated with each other). The significant positive correlations (typically exceeding 0.80) among metal pollutants suggest that they probably originate from the same source of pollution, although this analysis alone cannot identify that source. As stated earlier, Cr and Ni generally displayed exceptionally low concentrations that were similar for all storms, approaching the analytical detection limit, and thus were possibly at background levels. Similarly, Si was more associated with geological sources. As such, any correlations for these pollutants, or lack thereof, are likely not useful for correlating traffic with water pollution.

Metal concentrations are weakly and positively correlated with stormflow rates, which is surprising, given that our traditional conceptual model would suggest that higher flows would dilute a fixed mass of pollutants on impervious surfaces, resulting in lower concentrations (or an inverse correlation). Flow is more strongly and positively correlated with pollutant mass loads, largely because the total flow is used in the calculation to obtain mass loads (Equation (1)). A more detailed discussion of metal concentrations and mass loads at different hydrograph stages is presented in the next section.

Both metal concentrations and mass loads are positively correlated with the total number of vehicles associated with the storm wherein the samples were collected. In addition, the correlations between traffic volume and pollutant mass loads are stronger than between traffic volume and pollutant concentrations, as expected, for the reasons stated earlier. Indeed,

Figure 4 (bottom) shows that the correlation between pollutants and antecedent traffic is strong and positive for the first 10 days prior to sampling, as discussed in a forthcoming section. ADDs greater than 10 days were not included in the analysis due to street sweeping schedules. Sweeping removes pollutants from the streets. The city of Denver sweeps regularly in residential streets twice per month, but different neighborhoods within the watershed are swept on different days. The major highways, such as Federal Blvd and US Highway 6, are not swept as often, but the schedule is not regular. Part of the watershed is in the community of Lakewood, which has street sweeping about every 10 days, but the schedule is not regular, and again different neighborhoods have different schedules. Thus, we could not directly account for street sweeping. For these reasons, a 10-day antecedent period was deemed appropriate for this analysis.

Discussions on traffic’s impact on metal concentrations and loads at the different flow stages (Ff, Pk, R), as well as the impact of traffic during and after the imposition of the COVID-19 restrictions, on metal pollution are presented in the forthcoming sections.

3.4. Stormwater Metal Pollution at Different Hydrograph Stages

Numerous studies have been performed on stormwater quality during different hydrograph stages, particularly during the first flush (Ff) stage [

70,

71,

72]. Most studies stated that maximum pollutant concentrations occur either at the Ff or peak (Pk) stages, with the majority of them concluding that the largest loads typically occur during the Ff (e.g., [

68,

73]). However, the results from these papers regarding pollutant loads for various stages are not conclusive. For example, Flint and Davis [

68] evaluated stormwater quality in Mount Rainier (Maryland, USA) and stated that only about 33% of storms exhibited the highest pollutant load during Ff. Shumi et al. [

73] analyzed pollutants including Pb and Fe in Chongqing (China), concluding that there was no Ff effect in the study area. Few studies have reported loadings during the recession period. Our research showed that maximum pollutant concentration often occurs during the Pk (39%) and recession (R, 57%) stages, with fewer (4%) storms exhibiting the highest pollutant concentrations or loads during Ff (see

Table 3).

The results from

Table 3 show an irregular pattern of concentration among all pollutants (and other measured variables) at various stages within storm events. Those pollutant concentration variations within a given storm agree with the findings by Shorshani et al. [

11], who studied urban stormwater quality near Paris (France). In our research, for example, on 11 April 2020, similar concentrations were observed during all stages (Ff, R, and Pk) for all metals. However, on 15 May 2020, concentrations during the storm were very different for each stage and for each metal; for this particular storm, Fe concentrations gradually increased as the storm occurred. In short, there was no consistent trend of metals during the different flow stages. For example, Fe (a metal of concern) had peak values during the R stage in six out of eight events, while Mn displayed a peak concentration during R in four out of eight events.

Moreover, the correlation matrix between metal concentrations and related variables during various stages yields interesting results (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, upper left).

Figure 5 (top left) shows that for correlations during the Ff stage for all storms, metal concentrations are positively correlated with the flow (usually between 0.64 and 0.75), except for Si (−0.78) and Cr (−0.23), which as stated previously are probably not relevant due to not being related to traffic or being near background levels. That is, higher first-flush flows tend to have higher concentrations. Peak flows (

Figure 6, upper left) also exhibit moderate positive correlations with metal concentrations, although not as high as during the first flush, at generally between 0.10 and 0.35, except for Ba (−0.20) and Si (−0.38). Conversely, concentrations are weakly and mostly negatively correlated with recession flow (

Figure 7, upper left) for all the pollutants.

Interestingly, mass loads are positively correlated with flow at all stages of the hydrograph (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, upper right). Flow is used to calculate mass loads (Equation (1)), providing a partial explanation for this correlation, although concentrations are also used in the calculation, so in general we do not necessarily expect a strong positive correlation between mass load and flow. Mass loads also show higher positive correlations with the flow during Ff (0.51 to 0.96, with Si at 0.91) than at the other stages. However, the Ff correlation is only slightly higher than during Pk flow (0.25 to 0.91, with Si at 0.79) or R flow (0.51 to 0.88 with Ni at 0.47, Si at 0.89, Ba at 0.88 although as discussed before, Ni and Ba are likely not relevant). So, Si in all cases is highly correlated with flow, which generally results in higher sediment loads, as Si is typically associated with all sediment particles in the Rocky Mountain region [

40].

It is interesting that within each hydrograph stage, metal concentrations are linked to flow, but generally not as high as Si (which is likely sourced from sediment), which suggests that metal loading is not primarily from suspended sediments (and we do not expect this in an urban area). One potential explanation is that, for this small urban watershed, higher flows allow more runoff areas and pathways to be connected. That is, additional areas of the watershed become part of the runoff at higher flows, including additional metal sources and less polluted water infiltrating these previously excluded impervious surfaces. Additionally, a significant portion of the watershed is covered by natural areas, as explained previously. Finally, there could be a link between Si loads and construction activities within this urban watershed, but more research would be necessary to confirm this.

In terms of the impact of traffic on metal concentrations and loads at different hydrograph stages, all stages generally show positive correlations between 0.40 and 0.80, meaning the more vehicles there are circulating, the higher the concentration of most pollutants of concern (i.e., Fe, Mn, and Pb) and others like Zn, with the best correlations occurring during Pk (see

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, upper left), as discussed later. Correlations were even stronger when considering vehicular circulation and mass loads (see

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, upper right). The analyses shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 (upper left and upper right) were performed considering the vehicles that circulated during the day of sampling (until the time of sampling), i.e., during the first antecedent vehicular circulation day. Moreover, there was a strong correlation between metal concentration and mass load and vehicular activity for all ten antecedent circulation days (see

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, lower right and lower left), suggesting an acute effect of vehicular traffic on metallic pollution. The substantial contribution of vehicular traffic to metal pollution in stormwater, especially in the initial phases of runoff events, is highlighted by the significant correlations observed in this investigation. Typically, correlations weaken with increasing antecedent vehicular circulation days, suggesting a dilution or attenuation effect from other sources over time. The reasons for these high correlations over time are unknown.

In the correlation matrix, the Total Vehicles category exhibits positive correlations with the majority of metal contaminants throughout all hydrograph stages (see

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Correlations between total vehicles and pollutant concentrations are generally weak for Ff (0.47) and moderate for R (0.06 to 0.63). The correlations are stronger during Pk conditions (between 0.3 and 0.65), with Cu, Fe, and Pb particularly impacted by vehicle numbers. Stronger correlations for these pollutants are logical, since these metals are associated with traffic. Other studied variables such as flow (except the first flush, described above) and pH show weaker correlations with pollutants at the different stages, indicating a less direct influence compared to vehicle numbers.

We believe that mass loads are a more important metric for urban stream pollution because they are less subject to storm size and dilution, and theoretically more related to the source of pollution. In addition, mass loading is the most common way to regulate stream pollution (i.e., pollutant maximum daily load, TMDLs), even though MCLs are often used to indicate the severity of pollution. Correlations between pollutant mass loads and traffic revealed a similar trend as for pollutant concentrations, but stronger (see

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). During Ff (

Figure 5), the correlations between the number of vehicles and pollutants are generally lower than those during Pk and R (i.e., 0.42 to 0.56), and are remarkably similar for all pollutants, at about 0.40. During the Pk stage (

Figure 6), these correlations are stronger (0.58 to 0.81), where correlations for all metals except Si (0.63) are again remarkably similar to each other. During the R stage (

Figure 7), correlations are again stronger (i.e., 0.44 to 0.83). Overall, the correlations between mass loading and traffic suggest that traffic is likely a leading cause of metal pollution in our urban watershed during storms.

Increased traffic intensity leads to more pollutants, and the cumulative effect of this pollution may result in elevated contaminant concentrations and loads in stormwater runoff from high-traffic zones [

74]. Thus, high-traffic areas experience more frequent and intense abrasion of road surfaces, releasing metal pollutants, as investigated by Shajib et al. [

56]. Apeagyei et al. [

75] looked at how heavy metals were distributed in road dust in both urban and rural parts of Massachusetts (USA), concluding that road dust is a significant contributor to pollution in stormwater runoff. Wang et al. [

38] quantified the metals emitted from vehicles on an urban highway in Toronto (Canada) and found that Fe emissions are up to three times higher at highway sites due to the presence of more vehicles circulating. Similarly, Shorshani et al. [

11] simulated the integrated traffic, air, and stormwater quality in Grigny (France), concluding that the contribution of local traffic to stormwater contamination is significant for Pb and Zn, agreeing with our findings. Moreover, the exact impact on Swedish stormwater quality due to metals from traffic (particularly Zn) was described by Müller et al. [

57], while Czemiel Berndtsson [

30] studied stormflow in Trelleborg (Sweden) and concluded that heavy metal concentrations were directly correlated with the number of traffic vehicles. Additionally, Dang et al. [

76] studied pollutant concentration during stormwater runoff events in Nantes (France) and showed that wet weather events occurring during high-traffic hours contribute to elevated levels of stormwater pollutants such as Pb, Ni, Zn, and Cu. All those investigations agree with our findings, i.e., the more vehicles there are circulating, the higher the pollution in stormwater.

3.5. Effects of COVID-19 Restrictions on Stormwater Pollution

As discussed previously, we believe that mass loads are a better metric to evaluate sources, and these are presented in

Figure 3.

Figure 8 shows mass loads during the enforcement of the COVID-19 restrictions (labeled “Covid”) and after restrictions were lifted (labeled “After”). As discussed previously, the more useful traffic-related metals to consider are Fe, Pb, Mn, Zn, Cu, and Ba. Ni and Cr had very low, nearly constant concentrations (see

Figure A1) near the analytical detection limits, suggesting these may be background concentrations that are likely not related to any transient source, such as traffic. Cu, Ba, and Zn, while exhibiting low concentrations, are included because they are linked to traffic (as described earlier) and have variable concentrations well above background that could be linked to a source.

There was an increase in vehicular activity after the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted (from an average of 10,409 to 63,224 vehicles per day in LG, respectively), calculated based on data from

Table 2. Even though a scientific analysis of how the COVID-19 pandemic affected vehicular activity in Colorado has not been performed previously, Harantová et al. [

77] estimated the effect of COVID-19 on traffic flow characteristics in Slovakia and reported a 70% decrease in traffic during 2020. Moreover, Haghnazar et al. [

78] analyzed Pb and Zn levels in stormwater in the urban Zarjoub River (Iran) and found that during the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions, stormwater pollution decreased by 30%. Similarly, Chakraborty et al. [

79] also examined river water quality behavior in Damodar (India) and found that 100% of water samples were polluted after the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted, while only 9% of the samples collected during the imposition of restrictions were contaminated.

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the mass load is significantly lower for most metals during the enforcement of the COVID-19 restrictions compared to after restrictions were lifted. For instance, Fe shows a median load of about 100 mg/s during the restrictions, increasing to approximately 1000 mg/s post-restrictions. These results indicate that higher vehicle counts lead to substantially increased metal pollutant loads in stormwater runoff. More pollutant mass loads were documented when more vehicles were circulating, i.e., after the COVID-19 restrictions were lifted (see

Figure 8). In general, the results support previous research that has already been mentioned, suggesting that there is a correlation between increased metal levels in urban runoff in LG and increased traffic intensity in Denver prior to wet weather events.

Interestingly, a more important result might be that fewer vehicles on the road lowered the mass load of metal contaminants in stormwater runoff, suggesting that future sustainable urban development typically intended to reduce traffic should also improve urban water quality. Moreover, public habits that are becoming more common and result in less vehicular transportation (e.g., remote work, remote education, and online shopping) can also have a positive impact on stormwater quality in urban aquatic ecosystems. Similarly, stormwater management practices are needed to reduce the dangers that vehicle pollution poses to people’s health and the environment, especially in heavily populated cities. For example, elevated concentrations of metals in stormwater can be reduced by oxidation ponds and wetlands [

80], as well as infiltration-based technologies (e.g., [

81,

82]) and green infrastructure. For example, Walker and Hurl [

83] investigated the efficiency of a wetland in stormwater treatment, concluding that the concentration of metals such as Zn, Pb, and Cu can be decreased by 57%, 71%, and 48%, respectively, through the structure. Similarly, Jacklin et al. [

84] were able to remove most detectable metals using green infrastructure approaches. The current research suggests studying the long term trends of stormwater pollution after the COVID-19 pandemic and developing predictive models for simulating the impact of future traffic scenarios providing in-depth insights for both policy makers and urban planners. Following the discussion of findings in this research, it is also very important to acknowledge the limitations of this study, namely the traffic data collection process, in which we could have measured the data more accurately via physical surveys during the period of COVID-19 restrictions, and the results could also have been compared with the data collected from OTIS. Similarly, the water samples could also have been collected for more events at different times during the period of the COVID-19 restrictions, which could have increased the sample size, allowing for a more detailed comprehensive study. Future research should also consider the changes in land use patterns in relation to stormwater quality, which will be beneficial for understanding of urban pollution dynamics.

3.6. Innovative Points and Limitations of This Study

The innovative points of this study include highlighting the impact of traffic vehicles on heavy metal concentration, specifically the significant correlation between vehicular circulation and stormwater pollutants during and after the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions. Moreover, the results from this investigation provide valuable insights for urban stormwater pollution management, clearly suggesting that (1) even in a drainage area mostly occupied by residential land use (i.e., low traffic) with nearly 25% of the watershed covered by green and natural areas, urban stormwater quality can contain dangerous pollutants in concentrations above environmental standards, representing a risk to aquatic ecosystems, and (2) efforts should be focused not only on stormwater treatment practices but also on finding ways to decrease vehicular circulation, as previously discussed.

However, this investigation also involved some relevant limitations, such as the usage of a smaller dataset and limited observation times, which may not have captured the variability in pollutant concentrations. Therefore, future research should include continuous sampling to provide a better idea of how pollutant concentrations and mass loads change during storms. Even though such an approach is more expensive, it might be an important component in future investigations. Similarly, this study did not consider how land use and other variables such as rainfall intensity, wind speed, and other climatic variables affect stormwater pollution.