1. Introduction

Epoxy asphalt (EA), as a thermosetting and thermoplastic polymer composite material, has been widely used for steel bridge decks and specialty pavements due to its road performance, thermal stability, rutting resistance, and durability [1,2,3,4]. It is usually composed of two different components: one consists of epoxy resin, curing agents, and other additives, while the other is the asphalt component. A cross-linked network composite material is constructed by blending these two components and undergoing a curing reaction [5]. However, the compatibility between epoxy resin binder (EP) and asphalt is rather poor due to their differences in chemical structure, polarity, solubleness, and physical properties, which will lead to phase separation while they are blended and severely affects the stability and durability of the composite [6,7]. As such, some additivities, such as the modifier or surfactant, are usually necessary to adjust the composite compatibility.

To ensure the construction quality and material performance, EP content in EA should be over 50% to ensure the formation of a two-phase three-dimensional structure, where EP is the continuous phase, and asphalt is the dispersed phase [8,9]. However, excessive EP will reduce the fatigue resistance and low-temperature crack resistance of EA mixtures. Additionally, the increased cost of epoxy asphalt dramatically raises the construction costs, limiting the market application and promotion of EA. Therefore, numerous studies explored the microstructure and performance of EA components. For example, Chen et al. prepared EA with EP content ranging from 10% to 60% and studied the effects of different EP contents on the micro and macro properties of EA [10]. The results indicated that EA exhibited fine cost performance and met the performance requirements for steel bridge deck paving when the EP content was 40%. Yin et al. studied the properties of hot-mix epoxy asphalt (HMEA) binders with EP contents of 45%, 50%, and 55% [11]. They found that increasing the EP content slowed the curing reaction rate of EP, where EP existed as a continuous phase in HMEA binders and the resultant HMEA mixtures exhibited excellent high-temperature deformation resistance and fatigue crack resistance, which exactly met the technical requirements for steel bridge deck paving. Zhao et al. explored the comprehensive impact of different epoxy oligomer contents on the performance and phase separation behavior of hot-mix epoxy asphalt binders (HEABs) [12]. Their research demonstrated that the epoxy oligomer content had negligible effect on the phase separation microstructure of HEABs, and the higher epoxy oligomer content led to the increase in glass transition temperature and tensile strength of HEABs, while it resulted in the decrease in the break elongation. Despite the extensive research on different EP contents in epoxy asphalt (EA) binders, few studies have focused on the compatibility between EP and asphalt, as well as its impact on reducing the epoxy content. Furthermore, systematic research on the performance and microstructural evolution mechanisms of EA binders lacks as well.

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), as a one-dimensional material with electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and structural homogeneity, have been widely utilized in various composites [13,14,15]. In addition to these properties, CNTs have a relatively high specific surface area, which ensures good adsorption between CNTs and substrates, thereby enhancing the performance of the materials [16]. Mamun’s group found that nanomaterials significantly improved asphalt performance, but their potential in pavement engineering still requires further exploration [17]. However, strong Van der Waals forces exist between CNTs, which will lead to the easy entanglement or agglomeration of nanotubes when they are used in composites, limiting the performance and potential applications of the composites [18]. Based on such inherent drawbacks, chemical modification of CNTs are needed to enable their average dispersion. Chemical modification of CNTs can damage some of their internal structures and create defect sites that increase the chemical activity on their surfaces, which enhances the chemical bonding with epoxy resin molecules, thereby improving the compatibility between them [19]. However, this method will damage the original morphology and structure of CNTs, leading to a loss of strength in the nanomaterials [20,21,22,23]. Numerous studies have explored the functionalization and microstructural properties of CNTs. For instance, Hong et al. grafted styrene and maleic anhydride onto multi-walled CNTs, and the results indicated that functionalized multi-walled CNTs exhibited good dispersion in organic solvents and water with the structure almost unchanged [24]. Li et al. improved the dispersion of CNTs in polymers by applying shear stress during the melt processing, leading to more uniform distribution [25]. Chen et al. used cation–π stacking interactions and mild chemical modification to non-covalently functionalize multi-walled CNTs, improving the thermal conductivity and mechanical properties of epoxy resins [26].

Consequently, CNTs have been widely used in the modification of asphalt and thermosetting resin materials to improve strength, high-temperature performance, aging resistance, rutting resistance, and fatigue resistance of asphalt composite materials, as well as the mechanical properties and toughness of epoxy resins [27,28,29]. However, few studies have explored improving the compatibility between epoxy resin and asphalt by using CNTs. Herein, this work aims to discuss the correlation between the microphase structure and macroscopic performance of SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt. The light components (i.e., aromatic fractions) in asphalt can promote the swelling and dispersion of SBS, and these aromatic fractions have fine compatibility with the polystyrene part of SBS [30]. We used scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), and Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) to observe the dispersion of functionalized CNTs in epoxy asphalt. The effect of the amount of functionalized CNTs on the mechanical, rheological, and thermodynamic properties of epoxy asphalt was studied using dynamic shear rheology (DSR), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), and tensile measurement.

3. Results

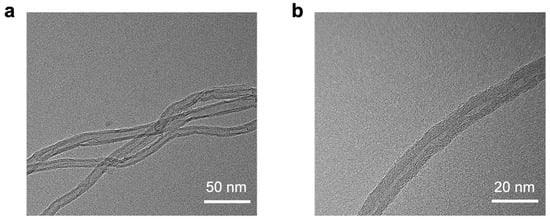

To investigate the effect of modification on the surface structure of CNTs, we used TEM to characterize the difference in surface morphology between the original and modified CNTs. It should be noted that the diameter of the SBS-CNTs was approximately 20 nm, which was much larger than the original CNTs (diameter of 12 nm, Figure 1), as shown in Figure 2. This increased size of diameter indicated that MA-SBS was successfully grafted onto the CNT surface via the reaction between -NH2 and -COOH (obtained after the hydrolysis of anhydride). In addition, the SBS-modified CNTs show the complete nanostructure with high aspect ratio with most of which existing as single bundle, and good dispersion was found due to the strong repulsive forces between the CNTs.

After successfully grafting SBS on CNTs, we blended the SBS-CNTs with epoxy asphalt and utilized the infrared spectroscopy to investigate the chemical structure of the resultant CNT-modified epoxy asphalt. Figure 3 shows the FT-IR spectra of the CNT-modified epoxy asphalt at different epoxy contents (from 0 to 30%) and the epoxy (30%) asphalt without the addition of SBS-CNTs (as a blank sample). The characteristic peaks at 1100 cm−1 and 1225 cm−1 correspond to the aliphatic ether C-O-C and C-O segments in the epoxy resin structure, while the peak at 1180 cm−1 corresponds to CN stretching vibrations. The broad absorption band at 3300–3400 cm−1 corresponds to hydroxyl stretching vibrations [31]. The peaks at 1600 cm⁻1 and 1500 cm−1 correspond to the aromatic ring backbone vibrations in the epoxy resin structure, and the peak at 830 cm⁻1 corresponds to the C-H vibrations in the benzene ring structure. Additionally, the characteristic peaks of the epoxy group at 910 cm−1 and 854 cm−1 have completely disappeared, indicating that the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt was fully cured [32].

It is usually difficult for CNTs (without any treatment) to disperse well in the bulk asphalt phase when directly blending the two. Our work aimed to strengthen their compatibility by grafting SBS onto CNTs’ surfaces. To observe the micromorphology of SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt, we used SEM to characterize the fracture surface of epoxy (30%) asphalt and CNT-modified epoxy asphalt at different epoxy contents, as shown in Figure 4. It was found that the composite materials exhibit good dispersion of CNTs in the epoxy asphalt. Such uniform dispersion not only enhances the interfacial bonding between the CNTs and the matrix but also alters the crack propagation path, reducing stress concentration in the matrix and forming an effective reinforcing network (Figure 4b–e). At the same time, the interface of the CNT-modified epoxy asphalt is relatively rough, and significant CNT pulling behavior is observed. This pulling behavior refers to the process in which part of the CNTs connects with the polymer phase and another part connects with the asphalt phase. The extraction of CNTs from the polymer phase consumes energy and time during the failure of the interface, thus delaying the break of the interface. Mohammad’s work on the application of nanocarbon fibers in asphalt mixtures noted that the pulling behavior of nanomaterials enhances the interfacial bonding of asphalt [33]. Therefore, the addition of SBS-CNTs strengthens the interface between epoxy and asphalt. As demonstrated in Figure 4a–e, phase separation was found between epoxy and asphalt, while there is no obvious phase separation between epoxy resin and asphalt after the addition of SBS-CNTs. This can be attributed to the functional groups on the surface of SBS-CNTs forming chemical bonds with the asphalt and epoxy resin molecules, enhancing the interfacial interactions and favoring the formation of large network structures of epoxy resin in the asphalt matrix.

To further investigate the difference in micromorphology of the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt with different epoxy resin contents, we used AFM to characterize the surface of the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and the CNT-modified epoxy asphalt at epoxy resin contents of 0%–30%. It should be noted that some apparent black defects exist on the surface of the original epoxy (30%) asphalt, as shown in Figure 5a. This arises from the phase separation between epoxy resin and asphalt due to their incompatibility. After adding SBS-CNTs in asphalt, no phase separation was found on the surface while the surface became rough (Figure 5b). Interestingly, it was found that the surfaces became more uniform while rough structure still existed after the addition of 10% epoxy resin (Figure 5c). Furthermore, there are no defects and an obvious rough structure on that surfaces where 20% to 30% epoxy resin were added in SBS-CNTs and asphalt composites (Figure 5d–e). These results indicate that SBS-CNTs and epoxy resin can enhance the compatibility between asphalt and epoxy resin, and homogeneous composite materials could be prepared at epoxy resin content over 20%. This, more than likely, can be attributed to the amidogen groups on the surface of CNTs that formed hydrogen bonds with the epoxy groups of epoxy resin, which tremendously improved the blending of SBS-CNTs and asphalt and enhanced their interlayer adhesion strength, resulting in the formation of uniform composite materials.

To explore the microstructure of CNT-modified epoxy asphalt, a polarized optical microscope (POM) with a hot stage was used to study the phase structure of the modified asphalt. During the high-temperature modification process, polymer-modified asphalts tend to undergo phase separation, leading to significant changes in phase structure [34]. Figure 5 shows the POM images of the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified epoxy (0%–30%) asphalt at 135 °C. It was found that typical phase separation—an island structure—was formed by the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy (10%) asphalt (Figure 6a,b). After blending SBS-CNTs and adding epoxy content (from 0 to 10% and 20%) in asphalt, it gradually changed from an island structure to a continuous structure with the increase in epoxy content, as shown in Figure 6a–d. When the epoxy content reached 30%, a bi-continuous network structure was observed (Figure 6e). These results indicate that CNT-modified epoxy asphalt enhanced the compatibility between epoxy resin and asphalt. Moreover, in contrast to traditional epoxy-modified asphalt, which requires more than 50% epoxy content to form a two-phase three-dimensional structure [9], our work revealed that CNT-modified epoxy asphalt can achieve the optimal morphological structure with only 30% epoxy content. This discovery not only effectively reduces the material costs, but also improves the construction quality, and provides an alternative approach for enhancing the compatibility between epoxy resin and asphalt.

Similarly, fluorescence microscopy was used to observe the microphase structure at different epoxy contents to further investigate the effect of SBS-CNTs on the microphase structure of CNT-modified epoxy asphalt. It was found that epoxy resin emits fluorescence under ultraviolet light (appearing as a bright green color) while asphalt and carbon nanotubes have no any fluoresce and appear black, as shown in Figure 7. Figure 7a shows the fluorescence phase image of epoxy-modified asphalt at 30% epoxy without any addition of SBS-CNTs. It should be noted that there is an uneven distribution of epoxy resin and asphalt phases with large agglomerates of asphalt. This arises from the high interfacial tension between epoxy resin and asphalt due to their discrepancy in polarity and solubility parameters, which hinders their effective mixing and dispersion, leading to the phase separation and aggregation of them. No fluorescence was found in SBS-CNT-modified asphalt without any addition of epoxy resin (Figure 7b). Figure 7c–e shows the fluorescence phase images of CNT-modified epoxy asphalt with 0.05% SBS-CNTs and epoxy contents ranging from 10% to 30%. After the addition of SBS-CNTs in epoxy asphalt (Figure 7a,e), the dispersed size of the epoxy asphalt particles gradually decreased and had more uniform distribution, revealing that the addition of SBS-CNTs reduced the interfacial energy between the two phases, enabling them to form a stable structural system. The continuous three-dimensional cross-linked structure was formed after the epoxy resin was fully cured, which can effectively encapsulate the asphalt in its matrix.

Asphalt, as a typical viscoelastic material, has viscoelastic parameters that are significantly affected by loading temperature and frequency under different conditions. The CNT-modified epoxy asphalt can form a three-dimensional cross-linked network structure of traditional thermosetting epoxy resin to coat the asphalt binder; it may provide the asphalt with enhanced mechanical strength and high-temperature stability. As such, it is necessary to analyze the effect of CNT-modified epoxy resin on the viscoelastic parameters of asphalt. Figure 8 shows the variation curves of the complex modulus and phase angle of the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified asphalt with different epoxy contents as a function of temperature. It was found that the complex modulus of the epoxy asphalt is higher than that of the asphalt without any addition of epoxy, illustrating that the high-temperature shear capacity of CNT-modified epoxy asphalt was better than that of the ordinary asphalt. When the epoxy content was 10%, the complex modulus of the modified epoxy asphalt showed little change compared to the unmodified asphalt. However, when the epoxy content was increased to 20%, the complex modulus of the modified asphalt undergoes an obvious change, indicating that epoxy resin has formed a well-structured network within the asphalt matrix, which improved the high-temperature shear resistance of CNT-modified epoxy asphalt.

The phase angle (δ) and complex shear modulus (G*) can jointly characterize the viscoelastic properties of asphalt. The complex shear modulus, G*, consists of the elastic modulus (G’ = G*cosδ) and the viscous modulus (G” = G*sinδ). A smaller δ value indicates that the asphalt behaves more elastically, which improves its high-temperature deformation resistance. In contrast, a larger δ value illustrates that the asphalt behaves more viscously. Moreover, the higher G* values and lower δ values represent higher rutting resistance of the asphalt [35]. As shown in Figure 8, when the epoxy content is above 20%, the phase angle is much lower than that at 10% epoxy content, indicating that a three-dimensional cross-linked network structure is formed with the epoxy resin content over 20%. The combined changes in the complex shear modulus and phase angle clearly show that SBS-CNTs effectively improve the compatibility between epoxy resin and asphalt, enabling the formation of a good network structure with low epoxy resin content. As such, a 30% epoxy content in asphalt shows excellent elastic recovery and high-temperature stability. This result can be attributed to the higher cross-linking degree of the epoxy asphalt phase structure in composite matrix at 30% epoxy content in comparison to the lower epoxy contents.

The rutting factor G*/Sinδ is used as an index to reflect the permanent deformation resistance of asphalt materials in the Superpave specification to characterize the high-temperature performance of asphalt [35]. Figure 9 shows the relationship between the rutting factor and temperature for the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified asphalt at epoxy contents of 0%–30%. It was found that the increase in temperature led to the decrease in rutting resistance. The rutting factors for the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified asphalt (0% epoxy), therein, were much smaller than those for the CNT-modified epoxy asphalt with higher epoxy content, indicating that the addition of SBS-CNTs and epoxy resin both increased the rutting resistance of asphalt. It should be noted that the 0.05% SBS-CNTs play a comparable role with 30% content epoxy modified asphalt, which both improved the high-temperature grade of asphalt. In addition, the rutting factor for epoxy contents above 20% (>300 KPa) was much greater than that for the lower 10% epoxy (<200 KPa), suggesting that SBS-CNTs promote the compatibility between epoxy resin and asphalt.

The glass transition temperature (Tg) can effectively reveal the polymer chain segment mobility of SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt and the compatibility between epoxy resin and asphalt, which was tested by DSC. Here, our composite materials were composed of thermoplastic asphalt, thermosetting epoxy resin, and SBS-CNTs, which would have Tg between those of thermoplastic asphalt and thermosetting epoxy resin. The non-isothermal DSC curves of the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified asphalt with epoxy contents ranging from 0% to 30% are shown in Figure 10. It was found that all the composite materials underwent a glass transition from a glassy to rubbery state during the measurement. The abrupt alteration in the DSC curve denotes the glass transition, and the peak value of the derivative of the DSC curve is defined as Tg. As such, the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified asphalt with epoxy contents of 0, 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively, showed Tg values of 11.9, 11.5, 12.5, 12.9, and 16.1 °C according to these non-isothermal DSC curves (Figure 10). The epoxy resin acted as a compatibilizer and enhancer, and it decreased the polymer molecular chain segment mobility of SBS-CNT-modified asphalt and increased the Tg. The increase in Tg of asphalt composite materials can improve their practical application in the construction of roads and bridges.

In addition, the tensile properties of the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified asphalt with epoxy resin contents ranging from 0 to 30% were measured, as shown in Figure 11. As the epoxy content increased from 0 to 30%, there were significant differences in the tensile properties of the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt composite materials. The increase in epoxy content resulted in the improved tensile strength of the composite materials, with the stress of the SBS-CNT-modified asphalt (0% epoxy) being <0.2 MPa, much lower than the 0.5 MPa and 0.6 MPa for the original epoxy (30%) asphalt and SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt at 10% epoxy content. It should be noted that the stress of the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt, respectively, increased to 1.9 and 3.3 MPa after raising the epoxy content to 20% and 30%, revealing the significant improvement of the tensile strength of the composite materials. Meanwhile, the elongation at break declined gradually with the increase in epoxy resin content, while the reduction became smaller as the epoxy content increased. It was found that the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt (at 10% epoxy content) showed a decline in elongation at break of 280% compared to the SBS-CNT-modified asphalt (0% epoxy resin), while the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt (at 20% epoxy content) exhibited a reduction in elongation at break of only 60% after further increasing 10% epoxy resin in the composite materials. And the elongation at break further decreased about 190% after adding the epoxy to 30% in the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt composite materials. The results revealed that the tensile properties of the composite materials abruptly changed between the epoxy content of 20% and 30%, suggesting that the composite materials underwent the transition from thermoplastic to thermosetting at an epoxy content of 20%–30%.

To investigate the mechanical properties and durability of epoxy asphalt under long-term load, we performed the repeated creep test. During repeated creep tests on the original epoxy asphalt with 30% epoxy and SBS-CNT-modified asphalt with 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% epoxy resin contents at 60°C, it was observed that the creep properties of the asphalt underwent significant changes as the epoxy resin content increased. Asphalt with low epoxy resin content (e.g., 0%) or epoxy (30%) asphalt without SBS-CNT modification exhibited larger initial strain, faster creep rates, and higher cumulative strain, indicating that it is prone to deformation at high temperatures and has poor fatigue resistance. In contrast, the SBS-CNT-modified epoxy asphalt with 30% epoxy content demonstrated lower creep compliance, slower creep rates, and smaller cumulative strain, suggesting better stability and durability at high temperatures. Additionally, as the epoxy resin content increased, the elastic recovery capability of the asphalt also improved. This means that under repeated loading, SBS-CNT-modified asphalt with higher epoxy resin content can better recover from deformation, reduce residual strain, and thereby extend the service life of the pavement structure, offering critical insights for engineering applications. (See Figure 12).

Source link

Pan Liu www.mdpi.com