1. Introduction

Hummus is a dip or a spread produced from boiled chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.). It is known for its creamy texture, flavor, and versatility, traditionally consisting of a balanced combination of chickpeas, tahini, lemon juice, garlic, and olive oil [1]. However, due to the diversification of global culinary preferences, there is growing interest in exploring novel ingredients and preparation techniques, even in traditional food products, such as hummus [2]. As chickpeas are the primary ingredient in hummus, any modifications applied to them are expected to significantly influence the aroma of the final product. One widely used technique for modifying plant seeds is malting, which is primarily applied to cereals [3]. Malting involves controlled hydration, germination, and drying of the seeds, which significantly changes the flavor and aroma of the product. Recent studies have demonstrated that malting can also be applied to various legume seeds, such as beans and lentils, impacting both their aroma and the composition of various antinutritional factors (such as the content of phytic acid or raffinose family oligosaccharides) [4,5]. During malting, various substances are released in the germinating seed, such as sugars or amino acids, which can then undergo so-called Maillard reactions during the drying stage of the malting and result in an increase of various flavor-active components present in the malted seed [6]. Additionally, during germination, certain enzymes, such as lipoxygenases, can transform various components of the seed into volatile compounds of diverse tastes and odor. One of the crucial reactions of these types is a chain of reactions that changes triglycerides into flavor-active aldehydes present in the malts [7]. Previous research about malting legumes (lentil seeds) has shown that malted legumes contain significantly different concentrations of volatiles than non-modified seeds [8]. However, the information about the use of legume seed malts in food production is actually very limited. Studies mainly concentrate on the technological properties of these malts. Current research about the uses of legume malts is mainly restricted to the use of legume malts in the brewing industry, which is not a typical technology where legume seeds are generally used.

Additionally, analysis of the volatile composition of the fermented products concentrates mainly on the components produced through the process of fermentation, not on the volatiles introduced from the malt [9]. It seems that the interesting avenue of research suitable for the analysis of legume malts would be the branches of the food industry, which typically rely on the use of legume seeds, not on malts produced from grains. As the legume malts are significantly different in many aspects from the unmalted legume seeds, the investigation of the use of these malts in various branches of the food industry can be an interesting and promising avenue for future research. The choice of ingredients in hummus production is pivotal in determining its sensory attributes, particularly its aroma. Aroma, an integral component of flavor perception, relies on a complex interplay of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that emanate from the food matrix [2,10,11]. The volatile profile of hummus is influenced by several factors, including chickpea variety, processing methods, and ingredient proportions [12,13,14]. As mentioned before, malting significantly changes the odor of the seeds; therefore, malts produced from the chickpeas used as a hummus ingredient could contribute to unique product flavor [6,7]. The goal of this study is to determine whether various chickpea malts (germinated by different lengths of time) and various contributions of the chickpea malt during hummus production can significantly change the aroma of the finished product.

2. Results and Discussion

The research consisted of an analysis of volatile compounds in six different hummuses, five produced from malted chickpeas and one produced from unmalted chickpeas (0D). The hummuses produced from malted chickpeas were differentiated by various lengths of germination. Sample 1D was produced from malt germinated for 24 h, sample 2D was produced from malt germinated for 48 h, sample 3D was produced from malt germinated for 72 h, sample 4D was produced from malt germinated for 96 h, and sample 5D was produced from malt germinated for 120 h. Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) allowed for the identification and relative quantification (using the internal standard method) of 22 volatile compounds in the hummus samples produced from malted chickpeas, germinated by various amounts of time (24–120 h). Table 1 shows the Kovats indices of the identified components, the percentage of the similarity search from the NIST library, as well as the perceived odor of the identified compounds and odor threshold. Table 2 shows the concentration of volatiles in the hummus samples measured using GC-MS utilizing internal standards for quantitation. Sample chromatograms and mass spectrum search results were provided in Supplementary Data.

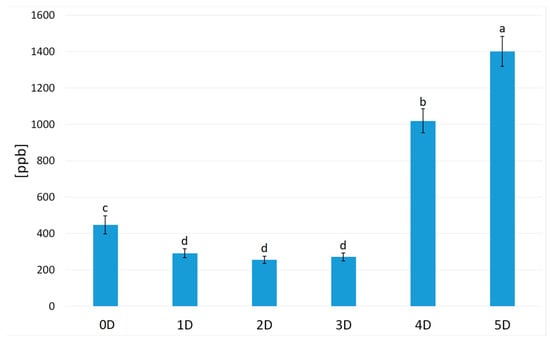

Most of the detected compounds belonged to the chemical group of aldehydes (nine compounds) and alcohols (five compounds). In the volatilome of hummus, three ketones, three pyrazines, one furan, and one terpene were also detected. The total concentration of volatiles in sample 0D was 448.03 ppb (Figure 1). Malts produced from chickpeas germinated for 24, 48, and 72 h were characterized by a lower concentration of volatiles, 291.15 ppb for 1D, 255.98 ppb for 2D, and 271.68 ppb for 3D. Germinating chickpeas by 96 or 120 h increased the total concentration of volatiles (1018.39 for 4D and 1401.67 ppb for 5D).

1-Hexanol is an alcohol associated with a beany, grassy off-flavor. However, its concentration in 1D, 2D, and 3D was approximately half that of the two times or almost two times smaller than in the 0D sample. This suggests that malts germinated for a short period of time (24–72 h) could be used in the production of hummus with a less intensive legume odor [29]. Ketones in legumes and malts are typically produced by lipoxygenases through the breakdown of fatty acid hydroperoxides [30]. One such ketone, 2-heptanone, is characterized by a fruity, spicy odor [31]. Samples 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D contained similar amounts of this compound, while its concentration increased significantly in 4D and 5D. This may indicate that lipoxygenase activity in chickpea seeds increases substantially only after 72 h of germination. Heptanal, an aldehyde formed via the autooxidation of oleic and linoleic acid—both present in the components of hummus—was found in the highest concentrations in 4D and 5D [32,33].

In contrast, 1D, 2D, and 3D contained over two times less heptanal than 0D. These results suggest that chickpea seeds inherently contain small amounts of this aldehyde, which may be reduced during the malting process, particularly through steeping or drying. However, by 96–120 h of germination, conditions appear favorable for the subsequent autooxidation of the fatty acids, leading to increased heptanal formation [32,33]. 2,5-Dimethylpyrazine is typically formed through the Maillard reaction between dipeptides and reducing sugars [34]. 4D and 5D contained significantly greater amounts of this compound than other samples, which exhibited similar 2,5-dimethylpyrazine levels. This suggests that the activity of hydrolytic enzymes, capable of releasing substrates for the Maillard reaction in which 2,5-dimethylpyrazine is formed, may become more active after 96 h or 120 h of germination.

Unfortunately, the gathered data do not allow for pinpointing the activity of one particular enzyme or group of enzymes responsible for limiting the formation of the 2,5-dimethylpyrazine in 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D. Future studies focusing on this aspect could provide valuable insights into the enzymatic processes influencing the volatile profile of malted chickpea hummus. Benzaldehyde is another compound that can be formed through the Maillard reaction [32,33]. Its primary precursor is the amino acid phenylalanine [35]. Characterized by an almond-like odor, benzaldehyde contributes to the aroma of various food products [36]. The germination time of the chickpea malts had a significant effect on the concentration of benzaldehyde. During the first three days of germination, benzaldehyde levels decreased, reaching their lowest concentration in the 3D sample. However, a significant increase was observed in samples 4D and 5D, where benzaldehyde content more than doubled compared to 0D. It is possible that benzaldehyde functions as a growth mediator and is only released after a few days of germination, but the elevated benzaldehyde level after four and five days of germination could also be the result of a higher concentration of phenylalanine and reducing sugars in germinating chickpea seeds [37]. The concentration of heptanol followed a similar pattern, decreasing in 1D, 2D, and 3D before increasing two- to three-fold in 4D and 5D. A study by Mao et al. (2024) [38] demonstrated that heptanol levels could either decrease or increase during germination, though the effect was variety-specific and was not measured across different germination durations.

Another volatile compound detected in hummus was 1-octen-3-ol, an alcohol characterized by undesirable ‘beany’ off-flavor; however, it is detected at a concentration of at least 100 ppb. Hummuses from the malted chickpeas contained a maximal 34.09 ppb of this alcohol, while 0D contained 12.37 ppb; therefore, changes to the level of this component due to the use of malted chickpeas in the hummus production should not deteriorate the aroma of the finished product [39]. The ketone 6-metyl-5-hepten-2-one, known for its fruity odor, has been previously detected in various legume seeds [40,41,42]. However, there is currently no consensus on whether the germination process increases or decreases its concentration [40,43]. In the analyzed hummuses, 4D and 5D contained the highest levels of this compound, followed by 0D, while 1D, 2D, and 3D exhibited the lowest concentrations. The concentration of 2-pentylfuran in 5D was five times greater than in 0D, whereas 1D, 2D, and 3D contained lower levels of this compound. This again suggests that chickpea malts germinated for 24–72 h exhibit significantly lower enzymatic activity than chickpea malts germinated for 96–120 h. Since 2-pentylfuran, which contributes a beany flavor, is primarily formed from linoleic acid lipoxygenase activity, its increased presence in longer germinated samples supports this hypothesis [44]. The concentration of 2-ethyl-3-methyl pyrazine followed a pattern similar to that of 2,5-dimethylpyrazine, with the highest levels observed in 4D and 5D. However, unlike 2,5-dimethylpyrazine, the concentration of 2-ethyl-3-methylpyrazine in 1D was lower than in 0D. The discrepancy may be difficult to explain, as 2-ethyl-3-methylpyrazine, unlike 2,5-dimethypyrazine, is a key aroma-active compound found in tahini paste [45]. Octanal, which has a ‘soapy’ and ‘fatty’ aroma [46], exhibited similar concentrations in 0D and 1D but decreased significantly in 2D.

In contrast, its concentration in 4D was three times higher than in 0D, while in 5D, it was over five times higher. Research by Rajhi et al. (2022) [43] has shown that germination generally increases octanal concentration in legume seeds. The concentration of 2-ethyl-1-hexanol remained similar across most samples, except for 1D, which had the lowest concentration. This alcohol, characterized by a rose-like aroma, is typically produced in the later stages of the chickpea development as a phytochemical with antifungal properties against Fusarium [47,48]. 3-Octen-2-one, another compound produced through oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, was most abundant in 5D, where its concentration was twice as high as in 0D [39]. Similarly, 1D, 2D, and 3D contained lower levels of this compound compared to 0D. A comparable trend was observed in benzeneacetaldehyde, with the highest concentrations detected in 4D and 5D and the lowest detected in 1D, 2D, and 3D. Benzeneacetaldehyde can be formed via the Strecker degradation pathway, Maillard reactions, or the oxidation of free fatty acids. Due to the complexity of these pathways, it is difficult to determine which precursor was in the lower concentration in the hummus samples [49,50,51]. However, these findings strongly suggest that 1D, 2D, and 3D exhibited lower enzymatic activity compared to the other samples. β-Ocimene was the only terpene detected in the prepared hummuses. The highest concentration was found in 0D, while all hummus samples prepared from malted chickpeas contained lower amounts. This terpene is naturally present in the legume seeds and may function as an insect repellent, which could explain its higher concentration in the hummus prepared from the unmalted chickpea [52,53]. 1-Octanol, an alcohol with an oily, aldehydic odor, can be generated through lipoxygenase enzyme activity [39,54]. As observed with many other compounds lipoxygenase-derived compounds, its highest concentrations were detected in 4D and 5D, while the lowest levels were found in 1D, 2D, and 3D. 3-Ethyl-2,5-dimethyl-pyrazine is characterized by a pleasant, nutty odor and has previously been identified in thermally treated chickpea products [55]. This pyrazine is typically formed through thermal amino acid generation, with 4D and 5D exhibiting the highest concentrations [56]. The lowest concentration was found in 2D. This suggests that chickpeas germinated for 96 h or 120 h contain the highest levels of free amino acids. However, it remains unclear whether this results from increased proteolytic activity or simply from the accumulation of amino acids due to extended germination.

Further research is needed to confirm these findings, but producing hummus from chickpea malts germinated for 96 h or 120 h could enhance the ‘nutty’ aroma of the product, as this compound is perceptible at very low concentrations [20]. Nonanal, an aldehyde primarily formed via linoleic acid oxidation, exhibited the highest concentration in 5D, nearly six times greater than in 0D [57,58]. Interestingly, nonanal was one of the few volatiles with significantly higher levels in 5D compared to 4D. This suggests that 5D may have either higher LOX activity or increased lipase activity, leading to a greater release of linoleic acid. Alternatively, the accumulation of free fatty acids in 5D might have facilitated higher nonanal formation during the drying process. However, to confirm these hypotheses, further studies on LOX and lipase activity in chickpeas would be necessary. Unlike nonanal, trans-2-nonenal, a key off-flavor compound in barley malts, did not exhibit drastic differences in concentration among the samples [7,59]. Multiple formation pathways have been proposed for trans-2-nonenal, including fatty acid oxidation, Maillard reaction, Strecker degradation of amino acids, oxidation of higher alcohols, and secondary oxidation of long-chain aldehydes [7]. In the analyzed hummus samples, trans-2-nonenal was present at relatively low levels, suggesting that its formation in hummus may differ from the typical lipoxygenase-driven pathway seen in the formation of other aldehydes. However, as with other volatiles, 4D and 5D contained the highest amounts of this compound, while 0D exhibited a concentration of this aldehyde compared to 2D and 3D. Trans-2-nonenal was not detected in 1D. Decanal, another aldehyde, showed considerable variation among the samples. Its concentration in 5D was nearly ten times higher than in 0D, while in 4D, it was slightly over three times higher. Interestingly, 1D and 3D also exhibited higher decanal levels than 0D, whereas 2D contained less than 0D. These results indicate that the decanal concentration is highly influenced by the germination period. Although the most probable source of decanal in legume seeds is fatty acid oxidation, the precise mechanism remains unclear, making it difficult to fully explain the observed changes in its concentration in hummus from malted chickpeas [37,60].

Undecanal was the only volatile compound, which was not present in the 0D but present in small amounts in all hummus samples produced from the malted chickpeas. This suggests that undecanal formation may primarily result from thermally induced lipid oxidation occurring in the malt during the drying [61]. Similarly, dodecanal, an aldehyde typically found in legumes in trace amounts, can originate from the oxidative degradation of palmitic acid [62]. However, the results of this study indicate that the process of malting does not significantly increase dodecanal levels in hummus. These findings demonstrate that using malted chickpeas in hummus production can alter its volatile profile, potentially influencing its aroma. The duration of chickpea germination could be manipulated to enhance or reduce the concentrations of specific aroma-active components in the final product. Future studies exploring consumer preferences for hummus with varying volatile profiles could provide valuable insights into the sensory appeal of these products across different populations.

Source link

Alan Gasiński www.mdpi.com