1. Introduction

Despite the improvements made in recent years in diagnosis and management, acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) remains a life-threatening disease [

1], with a mortality of 0.5%/h and over 23% in the first 48 h in medically treated patients [

2]. It has been described that one of every five patients with ATAAD die before hospital arrival, one of three within 24 h, and over half of all patients within 30 days [

3].

Patients’ outcomes following repair of ATAAD depend on many factors, such as age, clinical instability, presence of cardiac tamponade with shock, and organ malperfusion, particularly with cerebral damage [

4,

5,

6]. Surgical experience also plays an important role, since selection of the operative strategy in ATAAD repair is crucial for patient outcome. In fact, it has been shown that mortality for ATAAD is lower when repair is performed in high-volume rather than in low-volume centers by low-volume surgeons [

7,

8].

Recent guidelines define a high-volume aortic center as one that performs ≥7 aortic root, ascending aorta, or transverse aortic arch dissection repairs per year [

9]. However, since this definition may be somewhat arbitrary, as that concerning expert (ES) and non-expert surgeons (NES), this issue is still a matter of debate.

In the present article, we aimed to verify whether the results of ATAAD repair were influenced by the expertise of surgeons of our aortic team.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

The present study, which considers a time span between January 2010 and December 2021, enrolled a total of 199 consecutive patients who underwent surgery for ATAAD at our Center. We have divided the patients into two groups: those operated on by ES (n = 138) and those operated on by NES (n = 61).

Preoperative, demographic, intraoperative, and postoperative data were collected.

Acute kidney injury was defined by the increase in serum creatinine to 1.5 times from baseline, according to KDIGO [

10].

2.2. Center and Surgeon Characteristics

Our center performs an average of 20 ATAAD repairs per year. The aortic team, founded in 2010, manages all patients presenting with acute or chronic aortic pathologies; at the time of the present review, the aortic team included 8 cardiac surgeons, among whom there were 3 ES and 5 NES, as previously defined according to the consistency of their volume activity [

9]: ES performed at least 100 cardiac operations per year and a minimum of 7 ATAAD repairs, while NES were those in their first 10 years of practice or with limited expertise on aortic surgery, both in acute settings (<7 ATAAD repairs per year) and in elective surgeries for arch diseases. The surgical procedure was performed either by an ES or an NES and an assisting surgeon depending on the on-call shift, regardless of the clinical urgency or the dissection’s anatomical characteristics.

Since 2016, a systematic approach has been adopted in the treatment of ATAAD patients by creating a regional network and multidisciplinary teamwork with the goal of increasing early referral, simplifying the communication between hub centers (HC) and our spoke center (SC), and providing emergency radiological teleconsultation, thus minimizing the time between presentation and treatment [

11].

2.3. Patient Evaluation and Management

With clinical suspicion of ATAAD, definitive diagnosis is confirmed by transthoracic 2D-echo and/or angio-computed tomography (CT). Patients with a diagnosis of ATAAD in an SC are immediately referred to our HC, where, in the meantime, the aortic team decides the most suitable therapeutic strategy. In cases of uncertain diagnosis, imaging results are sent from the SC to the HC for consultation with the HC radiologists. Otherwise, if there is no surgical indication, the patients remain in the SC, and clinical and radiological consultation is maintained with the HC.

During transportation from the SC to the HC, continuous anesthesiological assistance is provided with monitoring of vital parameters (central venous pressure, systemic arterial pressure, and urinary output); hemodynamic instability and/or neurological impairment may entail patients’ sedation and intubation. Patients presenting to the HC emergency department are managed according to the same protocol before being transferred to the HC operating room.

2.4. Surgical Technique

Since 2010, surgical techniques have been standardized as previously described [

12,

13]. The preferred arterial site for cannulation is the right axillary artery, which has progressively replaced the femoral artery for the institution of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). When the entrance tear is identified in the ascending aorta, and the aortic arch is not dilated, only the ascending aorta and hemiarch are replaced with a supra-commissural graft. When, instead, the entry tear is located in the arch or the arch is significantly dilated even in the absence of tears, repair is extended to the aortic arch. Arch replacement is performed using a tri- or quadrifurcated graft with individual reattachment of the brachiocephalic vessels with or without the classic or frozen elephant trunk technique (FET).

Cerebral protection is obtained through the right axillary artery and antegrade selective perfusion of the left carotid and subclavian arteries under moderate systemic hypothermia (median lower temperature of 26 °C); when femoral artery cannulation is used for CPB, the arch vessels are selectively perfused.

2.5. Patient Follow-Up

Hospital survivors are followed by a dedicated team according to an institutional protocol that includes clinical and echocardiographic re-evaluation after 1 and 6 months and then yearly when also control CT scans are obtained. Afterwards, the patients undergo CT scans in the 2nd and 3rd postoperative years and then according to their clinical status. Further clinical information is gathered by phone interviews, medical records, and post-mortem reports to assess the incidence and type of major clinical and aortic-related complications.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

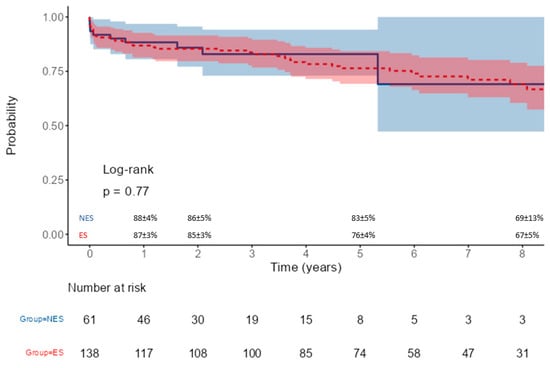

Continuous variables were tested for normality with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and expressed as median and interquartile range; comparison between groups was performed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages, and their comparison was performed by Pearson’s χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Survival analysis was obtained using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.

In order to explore factors associated with 30-day mortality, univariable and multivariable logistic regressions were performed, estimating odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Multivariable analyses included all variables clinically and statistically relevant, taking into account the number of events and potential collinearities.

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Discussion

Although advanced age, preoperative clinical instability, systemic organ malperfusion, and the need for complex repairs have been recognized as significant risk factors adversely influencing surgical results [

4,

5,

6,

14,

15], the role of surgical expertise in the outcome of ATAAD repair has not been fully evaluated. It has been previously shown that results are improved when repair of ATAAD is performed in high-volume centers and by high-volume surgeons [

7,

8,

16]. Indeed, the Mount Sinai group reported that lower-volume surgeons and centers have approximately double the risk-adjusted mortality than patients undergoing repair by the highest-volume care providers, with institution volume (less than 13 cases a year) and surgeon expertise (less than one ATAAD repair per year) as the strongest predictors of mortality [

17]. In others, surgical expertise not only improved early and medium-term outcomes but also allowed higher rates of valve-sparing aortic repairs in ATAAD [

18,

19]. It has been suggested that outcomes in aortic surgery could be improved in the United States if acute care and surgical treatment of most patients with ATAAD were regionalized and restricted to institutions with high-volume multidisciplinary aortic surgery programs [

20]. On the other hand, in the United Kingdom, it has been demonstrated that there is little relationship between volume and outcome at a hospital level, but higher individual surgeon volumes were associated with lower in-hospital mortality [

8].

When ATAAD repair is performed by less experienced surgeons, some factors could influence results, such as the possibility of being faced with more stable patients in high-volume centers while having more sick patients in low-volume institutions [

21]. Furthermore, it is unclear whether hospital volume can neutralize the surgeon volume or experience, acting therefore as a confounding factor [

8]. Large-volume institutions more frequently have a dedicated multidisciplinary aortic team that manages ATAAD patients according to established protocols, which is an important contributing factor to lower mortality in ATAAD repair [

22]. Indeed, centralization of ATAAD cases in a high-volume center had a positive impact on lowering mortality despite an insignificant increase in the number of patients treated, as did patient transfer from low- to high-volume centers [

23,

24,

25].

Despite surgical and medical improvements in the treatment of ATAAD, perioperative mortality remains high, being reported to be around 17% in a recent multicenter European registry [

13]. In the present experience, we observed a significant reduction in hospital mortality to 8% in the entire series, limiting our analysis to patients operated on during the last decade when we adopted a systematic approach in the treatment of ATAAD by creating a multidisciplinary aortic team. In the same period and with the aim to increase the number of patients receiving an early diagnosis and timely management, we also created a regional network establishing a 24 h connection between our HC and referring SC allowing inter-institutional patient evaluation, radiological teleconsultation, and immediate referral upon diagnosis confirmation. We consider all the aforementioned changes in our center policy and organization as key factors contributing to improving the surgical outcomes of ATAAD patients.

By analyzing the influence of surgical expertise on mortality in the same setting, we have found that, faced with a similar preoperative clinical profile of patients, ES performed more arch replacements with a mean duration of CPB and aortic cross-clamp comparable between the two groups. These results could be related to a difference in the surgeon’s decision-making process since they extended more frequently ATAAD repair to the aortic arch, being more confident with a more complex surgical procedure compared to NES. Considering the postoperative course, our analysis showed that NES patients had a lower incidence (albeit not significant) of permanent neurological damage and a lower hospitalization length with a similar incidence of acute kidney injury. There was a tendency of a higher surgical re-exploration rate for postoperative bleeding in the ES group; this could be related to the higher percentage of redo procedures and aortic arch replacements performed by ES. The 30-day mortality rate of the two groups was 8%; when analyzing the causes of death, it emerged that the patients operated on by expert surgeons suffered mainly from ischemic complications (36%), probably related to the severity and extension of the dissection, while in the NES group, the causes of death were mainly multi-organ failure and heart failure. Despite a higher number of arch procedures by ES, no significant difference was found in the incidence of aortic re-operations with a similar survival of >70% at the 5-year follow-up.

At multivariable analysis, preoperative cardiogenic shock and circulatory arrest time were independent risk factors for mortality; axillary artery cannulation was an independent protective factor, while surgical expertise did not influence 30-day mortality.

We believe that our overall results support the possibility that NES may acquire adequate surgical skills, allowing them to progressively shorten their learning curve, which, in our opinion, may also be a consequence of the standardization in the management of ATAAD in our institution from 2010. Furthermore, the present experience indicates that the adoption of a specific organization model for ATAAD patients, which includes a network connecting several SCs with an experienced HC, provides undelayed diagnosis, aggressive medical management, and expeditious surgical repair, which, together with standardization of surgical protocols and strategies, might have contributed not only to improving our surgical results but also to providing a more adequate surgical training of less experienced operators who may be involved progressively in the management of more difficult and higher-risk cases.