The Montezuma Wetlands drape across 1,800 acres of Solano County, California, where the Sacramento River empties into San Francisco Bay. Once drained and diked for farming and grazing, the marsh has been rehabilitated over the past two decades, and in 2020, tidal waters returned for the first time in a century. Today, the land teems with shorebirds, waterfowl, and other wildlife in a rare example of large-scale habitat restoration.

But just as the ecosystem is on the mend, another makeover may be coming. A company called Montezuma Carbon wants to send millions of tons of carbon dioxide from Bay Area polluters through a 40-mile pipeline and store it in saline aquifers 2 miles beneath the wetland. Approval could come in as little as 12 to 18 months once the county approves a test well, with what its backers call “limited disposal” coming one year after that. If the project proceeds, it could be the Golden State’s first large-scale, climate-driven carbon capture and storage site. Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency approved Carbon TerraVault, a smaller project in Kern County, California, that would store carbon dioxide in depleted oil wells.

Proponents say the area’s geology and proximity to regional industries make it an ideal place to stash carbon, and the company notes its facilities will be “well away from the restored wetland areas and far from sensitive habitats.” Residents and environmental justice groups argue that the project is being steered toward a low-income, working-class county long burdened with industrial development, and they worry about safety, ecological disruption, and whether the technology is a distraction from more effective and affordable climate solutions. Their fight over risk, consent, and who must live with climate infrastructure will help define not just the future of this project, but how California decides who bears the costs of decarbonization.

Long before becoming a showpiece of ecological recovery, the wetland in question was treated as expendable. Beginning in the late 19th century, the Montezuma Wetlands were transformed into farmland and shielded from natural tidal flows. By the end of the 20th century, much of the area functioned less as a marsh and more as a repository for industrial waste.

That began to change in the early 2000s, when University of California, Berkeley professor and environmental scientist Jim Levine led a remediation effort that used sediment dredged from the Port of Oakland to restore the wetland. The project was praised by regulators and conservationists and reestablished tidal habitat, altering the trajectory of a landscape long defined by extraction.

Levine’s involvement with the site evolved, eventually placing the Montezuma Wetlands at the center of a vastly different environmental experiment. Around 2010, scientists with Shell and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory identified the area’s shale composition as potentially suitable for storing large amounts of carbon dioxide. As California’s climate targets grew more ambitious, Levine began promoting the site as a place where those geological conditions could support a large-scale carbon capture and storage project.

In May 2023, Montezuma Carbon sought an EPA permit to inject CO2, sourced from refineries, hydrogen plants, and power plants, into the Montezuma Wetlands. The project, designed by scientists with the Lawrence Berkeley lab, Stanford University, and UC-Berkeley, stalled last spring as Levine’s health declined. After his death in September, its technical lead, seismologist and Berkeley professor Jamie Rector, wanted to “do right by Jim” and reignite the proposal, positioning it as both a climate solution and a research-driven test case — even as scrutiny and opposition have intensified.

“Solano County historically has long been treated as a waste dump for the region’s polluters,” said local pediatrician Bonnie Hamilton. “We have a beautiful area and don’t want to see it messed up for the sake of rich people wanting to get richer.”

Opponents frame Montezuma Carbon’s proposal as a question of who controls their land and who absorbs the risks of decarbonization. The county is home to roughly half a million people, including the Bay Area’s largest per capita populations of veterans and residents with disabilities, and it is among the most racially diverse counties in the nation. Limited resources can make navigating regulatory and legal processes difficult, heightening concerns about meaningful consent. Those worries are compounded by a history of industrial violations, including an $82 million penalty levied last year against the Valero refinery in Benicia for years of unreported toxic emissions and other air quality failures.

Within the next three years, the project’s architects hope to be depositing up to 8 million tons of carbon annually, a significant stride toward the state’s goal of capturing 13 to 20 million tons by 2030. Rector believes the site could store at least 100 million tons over its 40-year lifespan. The site’s compacted mud, silt, and clay, he said, would provide a natural cap that could keep the pollutant locked underground indefinitely, while its location alongside Bay Area industries would reduce carbon transportation costs.

Daniel Sannum Lauten / AFP via Getty Images

The National Energy Technology Laboratory, which leads the Energy Department’s research on carbon capture and storage, points to key advantages of the site like minimal environmental sensitivity and low population density. The nearest community, Rio Vista, is 10 miles away. Rector added that advanced pipeline monitoring systems, such as acoustic, pressure, and temperature sensors, can quickly detect and contain leaks. Unlike enhanced oil recovery — where pressurized CO2 is injected to extract oil, with regulations aimed primarily at protecting groundwater — EPA rules for climate-driven sequestration require operators to demonstrate that injected carbon will remain buried. The project’s proponents also argue that decades of experience pumping carbon underground — including more than a billion tons injected in the U.S. for commercial use, such as for beverage carbonation, since the 1970s, and over 20 million tons that have been safely stored at Norway’s Sleipner project since 1996 — suggest that Montezuma is a low-risk site.

Pipeline safety has drawn heightened scrutiny since 2020, when a carbon dioxide pipeline ruptured in Satartia, Mississippi, casting a dense cloud of gas near the ground and hospitalizing dozens of residents. Although that pipeline was federally regulated, critics and regulators alike later acknowledged those rules were inadequate for managing the public safety risks of large-scale CO2 transport.

Rector quipped that the project would leak “when pigs fly,” but identified pressure-induced seismicity as the principal peril, given the wetlands’ position between the Kirby Hills and Midland faults — though the National Energy Technology Laboratory has said a devastating event is unlikely. To reduce that risk, Rector has proposed drawing down water from a nearby reservoir to ease subsurface pressure and create more capacity for injected gas, with the water potentially redirected to farmers and industries facing chronic shortages.

Carbon capture and storage is widely seen by policymakers, industry leaders, and many scientists as a necessary — if imperfect — tool for meeting state climate goals, even as environmentalists argue it diverts attention from cheaper, cleaner solutions. California Governor Gavin Newsom has said “there is no path” to carbon neutrality without the technology, a point the California Air Resources Board echoed when it told Grist it “could not weigh in on specific projects, but carbon management is a critical piece of the state’s plan to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045.” This institutional support is reflected in legislation like SB 614, which stresses the technology is central to California’s effort to reach net-zero emissions.

Supporters argue that the value of carbon capture is most obvious in sectors where greenhouse gases are hardest to curb, such as cement production, which accounts for roughly 8 percent of global CO2 output. While lower-carbon materials and cleaner manufacturing techniques are emerging, they will be costly and slow to deploy at scale. Even with those changes, substantial emissions would remain, said Ben Grove, a deputy director at the Clean Air Task Force, leading him to consider carbon capture a necessary complement to other climate solutions.

For Montezuma Carbon, that high-level backing has yet to translate into financial certainty. Project leaders say technological advances that could lower costs, along with government incentives and private investment, are still essential.

Still, the company faces significant hurdles, including regulatory approval and the loss of its founder. Cost is now the “albatross around our neck,” Rector said, as the project has no financing and is estimated to require roughly $2 billion. The Department of Energy denied a $340 million grant in 2023, and Rector acknowledged that without government subsidies or a promising return for investors, funding will be difficult.

In its EPA application, Montezuma Carbon contends the project would bring jobs, tax revenue, cleaner air, and a hub for climate innovation to “disadvantaged local communities.” Residents and local environmental justice advocates don’t buy it. They also argue the technology will only perpetuate the use of fossil fuels. The International Institute for Sustainable Development considers carbon capture and storage “expensive, energy intensive, unproven at scale, and has no impact on the 80 percent of oil and gas emissions that result from downstream use.” Similar carbon pipeline schemes have failed in the Midwest because of community opposition, and Montezuma Carbon is just one of a dozen such projects under consideration in California.

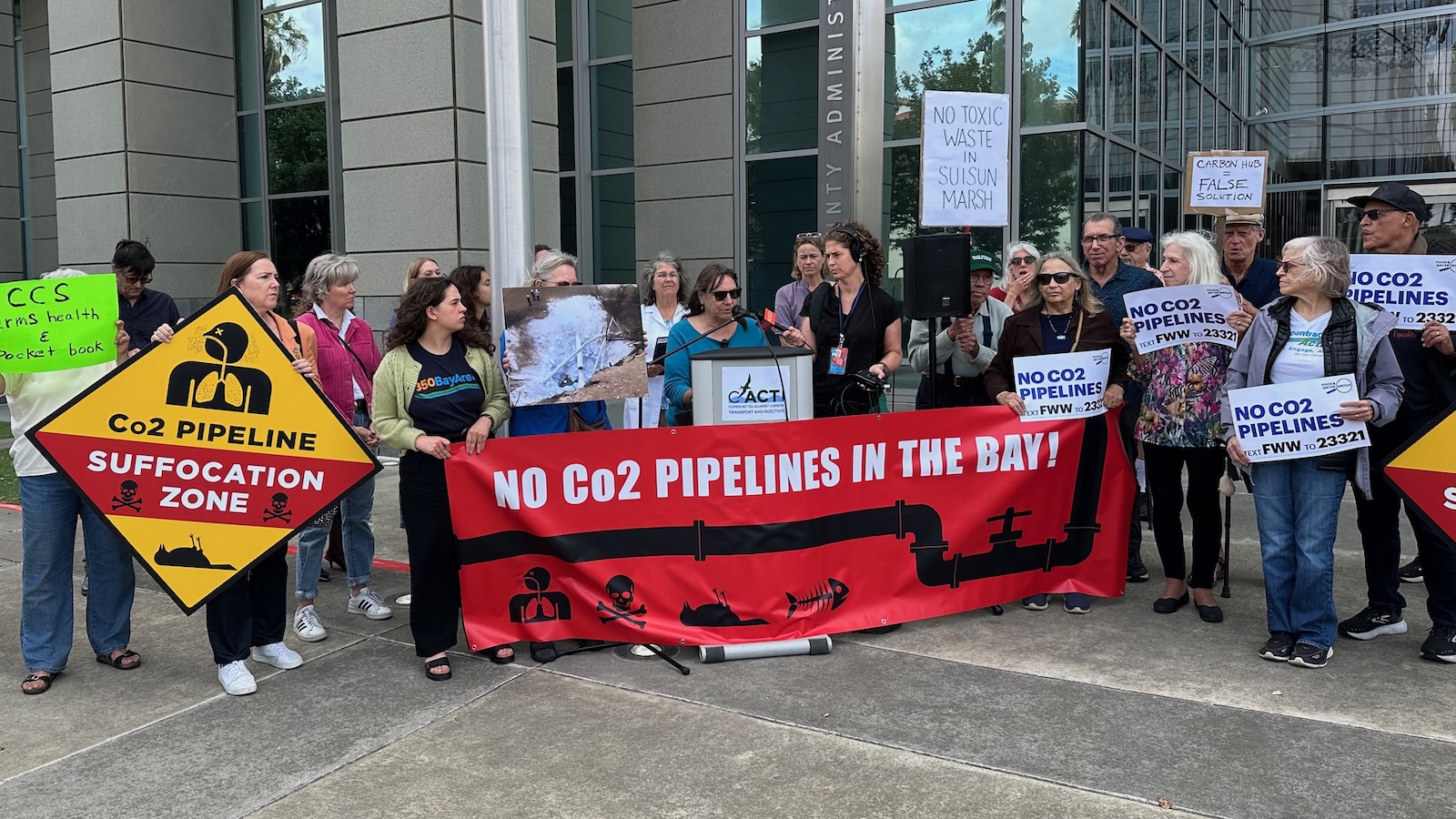

Tom Kunhardt, Communities Against Carbon Transport and Injection

Local officials are reviewing California’s first geological carbon storage project, in Kern County, as they try to understand how similar proposals have been evaluated elsewhere. County Supervisor Cassanda James “does not have a comment at this time,” according to her chief of staff, and other county supervisors did not respond to requests for comment. Alma Hernandez, the mayor of Suisun City, which is about 20 miles from the proposed site, said her staff is “still learning more” about the project and “no position has been taken.”

For many residents, the unanswered questions go deeper than permitting or precedent. They ask whether industries labeled “essential” must continue emitting carbon dioxide at all, or whether cleaner alternatives could negate the need for technologies like underground storage. And they question who gets to decide which communities should host infrastructure designed to manage the consequences of pollution generated elsewhere. “All of us want to believe the climate crisis could be solved without changing how society functions,” Theo LeQuesne of the Center for Biological Diversity said.

The Montezuma Wetlands have endured centuries of human interference, first in its destruction and then its restoration. It now faces another possible refashioning to manage emissions from an economy that still rests solidly on fossil fuels.

At the heart of the debate is not only whether carbon capture is an effective way to meet California’s climate goals, but where such infrastructure should be built, and who gets to decide. The fate of the project hinges on the weight of statewide climate ambitions, scientific confidence in the technology, and the objections of the community being asked to host it.

Source link

Miranda de Moraes grist.org