1. Introduction

The interactions between wildlife and forest ecosystems are essential for preserving biodiversity and maintaining ecosystem health. They support the sustainable management of natural resources—both game and timber—by enhancing biodiversity through seed dispersal, pollination, and species diversity; regulating ecosystem processes via predation, herbivory, and nutrient recycling; and maintaining habitat structure for forest resilience [

1,

2,

3]. In some temperate areas in Europe, ungulates have increased in number over the past decades, creating imbalances between conservationists, ecologists, farmers, wildlife managers, and forest managers [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Noticeable shifts in ungulate populations have coincided with climate change and advances in agricultural practices, which have improved forage conditions. As a result, there have been significant increases in both the populations and the range of these species [

9,

10]. Throughout Europe, the overabundance of ungulates has resulted in damage to the agricultural sector through reduced yields of several crops, damage to the forestry sector due to browsing, fraying, and trampling, and human safety concerns stemming from vehicle collisions [

11,

12]. This study specifically focuses on the damage within the forestry sector caused by browsing. Ungulate browsing is represented by the consumption of vegetal material other than bark from young saplings which interfere with the normal development of the plant.

Browsing is a well-researched topic in the literature, with over 155 research papers published in Europe, of which roe deer (

Capreolus capreolus L.) is the focus of 95 studies and red deer (

Cervus elaphus L.) is the subject of 93 studies [

13]. One trend in the study of browsing focuses on the damage inflicted on coniferous species, particularly the replacement of more palatable species like silver fir (

Abies alba Mill.) with less palatable ones such as Scots pine (

Pinus silvestris L.) and Norway spruce (

Picea abies L.) in Central and Southern Europe [

4,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Another trend is the preference for broadleaved species over coniferous species in mixed plantations, as their palatability is much higher [

20,

21]. This is the case for oak species [

22,

23,

24], which are part of mixed regeneration with less valuable species; however, oak typically serves as a future crop tree [

25]. Therefore, the loss experienced is not only ecological but also economic. Even if the browsed saplings survive, it has been shown that the future timber depreciates due to the development of multi-stem trunks and the onset of additional diseases that affect timber quality [

26].

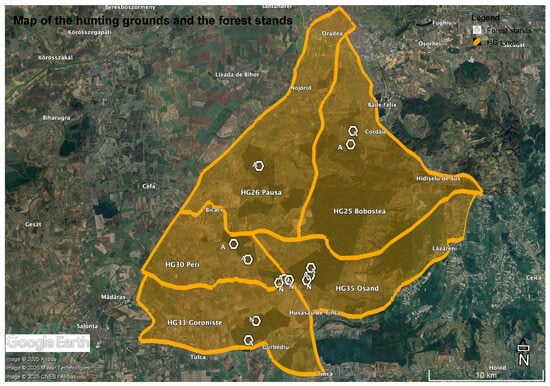

This is particularly evident in the Western Plains of Romania, where populations of red deer (

Cervus elaphus L.), fallow deer (

Dama dama L.), and roe deer (

Capreolus capreolus L.) have increased in numbers. The study area is characterized by large-scale, intensive agriculture on flat terrains, bordered by forests, similarly to areas found in the Hungarian Great Plain [

27]. Ungulates utilize the agricultural fields as both feeding and resting zones [

28,

29] almost year-around, with the exception of late winter and early spring when the crops are harvested and no abundant food is available. During their refuge period in the forests, the overabundant ungulates exploit all available resources. However, due to intensive browsing, the tree species struggle to develop adequately or survive in order to reach the canopy stage [

30].

The aim of wildlife managers is to maintain the population at a level which the ecosystem can support, while preventing the loss of genetic diversity, enhancing the long-term survival, and reducing the damage caused to the other sectors [

31]. In most of the cases, the economical compensation has to be covered by wildlife managers [

32]; however, in some situations, the legislation does not provide enough flexibility to manage the population effectively, as the behavior of the ungulate species has significantly changed, resulting in an increased natural annual growth [

6,

33]. Similarly, forest managers have to assure that the forest will develop properly and to use preventive measures against ungulate browsing, such as fencing or the use of repellents [

34]. Some silvicultural practices are also influencing the levels of damage, as the silvicultural system uses different regeneration techniques with highly varied sapling densities [

35].

This study provides the first assessment of ungulate browsing in young oak stands in Romania and evaluates ungulate occupancy in forests with high ungulate densities. Analyzing browsing from both forestry and wildlife management perspectives, it aims to clarify the primary impact of high ungulate density—exacerbated by intensive agriculture—and to identify secondary factors based on local silvicultural practices. A comparison between actual and optimal ungulate populations, using Sustainable Population Threshold (SPT), offers a clear visualization of density discrepancies. The findings will equip wildlife and forestry managers with crucial insights to mitigate browsing damage.

4. Discussion

This study presents the first assessment of the impact of ungulate browsing in oak-dominated forests in Romania, as previous studies have primarily focused on coniferous species such as the Norway spruce and Scots pine [

44,

45,

46]. It includes the first quantification of the overabundance of red deer, fallow deer, and roe deer, based on scientific calculations of the Sustainable Population Threshold, which simultaneously considers economic, social, and ecosystem sustainability. The findings of this study are particularly significant from a wildlife management perspective, as they quantify the SPT and actual densities of ungulates, providing evidence for the need for new hunting regulations that can be applied in similar scenarios.

Ungulates typically exhibit a preference for certain tree species and browse them in a particular order [

47,

48,

49]. However, in this study, the tree species did not influence the selection process, as ungulate density was so high during the refuge period that a shortage of forage occurred, leading to non-selective consumption. The same lack of selectivity under high densities was also identified in a study conducted in Italy [

16]. The vigor of the sapling influences the browsing selection process [

50,

51], but in this study, this factor appears to be insignificant, further demonstrating that overabundance leads to non-selective consumption. The only factors found to be significant in this study, with ungulate densities 3.7 times higher than the SPT, are forest cover and the silvicultural system. The five hunting grounds that overlapped with the study area had varying proportions of forests and agricultural fields. When the share of forest area in the total hunting ground was below 20%, browsing probability was found to be significantly higher. This can be attributed to a reduced refuge area during critical periods of the year, as many more animals moved into the forests after crop harvesting. Silvicultural treatment plays a vital role in ungulate browsing phenomena, with the probability of browsing occurrence being significantly higher in clearcut systems that employ artificial regeneration with low planting density [

4,

16,

35,

52]. In clearcut fellings, not only is the planting scheme considerably lower, but also a light gap is created, facilitating the appearance of grasses and shrubs [

53]. In the shelterwood system, natural regeneration is prioritized, and the gaps created through the removal cuts are significantly smaller than those produced by the clearcut system. The removal cuts are executed after prior establishment cuts, which are performed following fruiting years to promote the establishment of a continuous cover of saplings [

54]. Also, the planting scheme is not established by foresters and depends on the fructification and germination capacity, which in some cases, such as the European beech can reach up to a million seedlings/ha in the seedling phase [

55]. While in the clearcut fellings, the planting schemes are adopted based on the future crop trees technique and to facilitate the silviculture works in the tending phases. In natural regeneration cases, the density is regulated through natural competition and through tending operations [

56,

57]. In a similar study situation in Austria, it was found that the browsing predisposition is lower in shelterwood systems and higher in clearcut systems [

35]. The same study admits that in Austria, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland, a more “close-to-nature” silvicultural can reduce the risk of browsing damage by decreasing habitat attraction for ungulates and favoring abundant regeneration [

58]. It needs to be noted that a continuous silvicultural system with natural regeneration is not exempt from the browsing phenomena, but due to a much higher sapling density, the impact is not as visible and economically harmful as in the case of artificial regeneration. In this study, the browsing occurred in the clearcut fellings at an average of 49.65% browsed saplings in an average density of 4980 saplings/ha, while in the shelterwood system at an average of 12.8% browsed saplings in an average density of 12.830 saplings/ha. Even if the proportion of browsed species is quite different in the two cases, the number of browsed saplings is higher in both cases, with an average of 2472 saplings/ha browsed in artificial regeneration and 1642 saplings/ha browsed in the natural regeneration.

To mitigate damage caused by ungulate browsing in the long term, forest managers should adapt their management process to adapt to the situations caused by the climate change and the impressive growth of ungulate number [

59], adopting a silvicultural system with higher regeneration density and with mixed composition [

60]. Measures such as fencing [

61,

62,

63], tree guards [

64], repellents [

65], and natural obstacles [

66,

67] are solutions to prevent damage from browsing, fraying, and trampling; however, they are costly and require continuous maintenance, which can place a burden on forest managers [

68].

The biggest emphasis should be put on the management of the wildlife species to control the number of ungulates. The current legislation [

69] in Romania heavily regulates hunting processes, with quotas determined by annual evaluations of game species. In the study area, ungulate populations have reached alarming levels, suggesting that the existing legislation may not be appropriate for this situation. At densities 3.7 times higher than the SPT, the densities of ungulates should be considered to be an overabundance. Similarly, in Lithuania, the hunting law [

70] establishes a maximum limit of 28.75 red deer equivalents per 1000 ha of deciduous and mixed stands of deciduous trees with coniferous species. However, the legislation allows for the culling of red deer, fallow deer, and roe deer without a designated hunting season or quota. In Italy, a similar equivalent system was used in the elaboration of the Ungulate Density Index (UDI), where the UDI was employed to quantify the magnitude of ungulate abundance [

16]. In commercial forests in Scotland, the tolerable threshold of red deer was considered to be 4 deer per 100 ha [

71]. In Germany, the tolerable densities for roe deer depending on habitat quality have been suggested at between 4 and 12 roe deer per 100 ha [

72]. Relying on the current quota system from Romania’s hunting law [

69] may be considered outdated in this case, indicating that special regulations granting greater flexibility to wildlife managers might be needed, and higher quotas should be adopted. Similar cases were identified in Germany [

73], where non-selective culling has been adopted to control game numbers. An additional hunting season should also be implemented for red deer, allowing the harvesting of two-year-old specimens that are not participating in reproduction by professional hunters. In high-density populations, particularly among cervid species, individuals experience a reduction in body weight [

74,

75]. To effectively control the damage caused by ungulates to forest ecosystems, a comprehensive set of hunting regulations and practices should be implemented in critical areas of overabundance. These measures should aim to reduce the populations of both males and females to optimal levels while preserving genetic diversity and maintaining the overall health of the game.

In terms of combined wildlife and forest management, this study can be viewed as an interdisciplinary effort that addresses both sectors simultaneously. Future research on ungulate browsing should not only present actual ungulate densities but also calculate an SPT. Since the term “overabundance” can sometimes be ambiguous, it is essential to establish a clear threshold between actual and optimal numbers to determine if an area is experiencing ungulate overabundance. Future studies should focus on viable solutions to reduce damage levels in areas with high ungulate densities while also identifying effective methods for controlling ungulate populations.