1. Introduction

In the absence of a standardized, universally accepted definition of this condition, FGR and small-for-gestational-age infants are often superimposed. The real overlap is only partially accurate since a small number of FGR have appropriate-for-gestational-age birth weights, and some SGA infants are intrinsically small, without being restricted and without the high probability of a poor outcome. However, the equivalence FGR to SGA will be kept throughout our work, the main reason being that in our region of Romania, there is a large proportion of pregnancies that do not receive adequate obstetric monitoring and thus might lack the proper diagnosis of fetal growth restriction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

We performed a comparative analysis on two retrospective cohorts of infants born in our maternity hospital, a referral unit for the region of Romania with a high incidence of fetal growth restriction and high-risk pregnancies.

As inclusion criteria, we used FGR (per the definition above) and singleton live pregnancies. The exclusion criteria were birth weight above the 10th percentile, twin/multiple pregnancy, severe congenital malformations, and stillborn infants.

The first cohort is the “historical cohort”, which is made up of 912 infants with FGR born over three years (2010–2012)—Group H—and the second one is the “contemporary cohort”, which contains 937 infants with FGR also born over three years (2020–2022)—Group C.

This study was approved by the university’s Research Ethics Council (no. 250/27 December 2022). Informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians of all subjects involved in the study.

2.2. Data Collection

For both cohorts, we collected items we deemed influential for the prevalence of FGR (pregnancy follow-up, gestation, parity, education, occupation, smoking, living circumstances—rural/urban, maternal hypertension) in order to detect the emergence of certain patterns over the course of ten years. All information was freely provided to the attending neonatologist by the mother upon the first interview after birth. We also collected data regarding the neonates, such as sex, gestational age (GA), birth weight (BW), and length.

2.3. Data Preprocessing

The initial dataset contained missing values, which were handled via imputation using the k-nearest neighbors (kNN) algorithm implemented in the VIM package in R. The kNN algorithm was applied with k set to 5, which identifies the 5 nearest neighbors for each missing value based on Euclidean distance. Imputed values were assigned from these neighbors. This method allows for robust imputation by leveraging similarities within the dataset while preserving the integrity of the original data structure. This resulted in a clean dataset that was suitable for analysis.

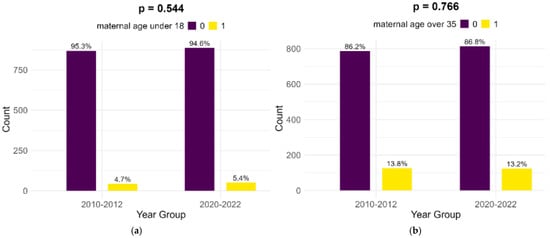

2.4. Statistical Comparison Between Time Periods

To evaluate differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between the two time periods (2010–2012 and 2020–2022), we used the Wilcoxon rank sum test for numerical variables due to their non-normal distribution and the chi-square test for categorical variables. The Wilcoxon rank sum test is a non-parametric test that compares the medians of two independent groups and is suitable for non-normally distributed data. The comparison of numerical variables between the two groups is visualized using density plots. The chi-squared test assesses the association between categorical variables by comparing observed frequencies with expected frequencies under the null hypothesis of no association. The comparative analysis of the categorical variables is plotted using a cluster bar graph.

All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio 2024.04.1. The following R packages were utilized: VIM for data imputation, caret for data partitioning, broom for tidying model outputs, dplyr and tidyr for data manipulation, ggplot2 for plotting, and readxl for data import.

3. Results

The global incidence of FGR in our study was 5.13%, with non-significant differences between the two time periods (5.03% and 5.25%, respectively).

4. Discussion

In our study, the incidence of FGR was 5.13%. This figure is conclusive with worldwide estimates but should be considered cautiously, as it obviously does not include FGR with BW above the 10th percentile.

In our study, the level of maternal education has changed from the historical cohort to the contemporary cohort; in the latter, mothers of infants with FGR exhibit lower percentages for any education, as well as primary and secondary education, but higher numbers when it comes to higher education (high school and university). The higher number of mothers residing in a rural area may also impact school availability and attendance.

Our study shows improvement during the ten years between the periods we analyzed regarding employment; more women have stable jobs and stable incomes in the contemporary cohort compared to the historic cohort. Unfortunately, there is little change regarding smoking during pregnancy in the considered time frame, even a small, non-significant increase in the number of smokers. Also, smoking was shown to have a significant inverse correlation to prenatal care.

One surprising correlation that we found is between prenatal care and prematurity—the latter was found in 17.9% of medically surveilled pregnancies, compared to 10.4% in pregnancies in which the mothers did not receive prenatal care. This can be either iatrogenic prematurity as a result of excessive obstetric interventions (similar to the article cited above) or prematurity as a result of pregnancy-related conditions that require surveillance.

Our results show a peculiar dynamic of parity in the two lots; there was an increase in the number of primiparous women and women giving birth for the third time and a decrease in women having a second baby or multiparous women. The primiparous women were always the most commonly observed during both time periods, which is in line with the research mentioned above.

Lastly, but perhaps most relevant to our study, prenatal care has seen a dramatic increase over the past ten years, which is linked to higher maternal education and the urban residence of the mother, thus indicating better access to and understanding of life-saving medical information.

Strengths and Limitations

One weakness of our study, which possibly accounts for the differences in the prevalence of cases compared to other studies, is the overlapping of FGR and SGA due to the fear that if we were only to consider pregnancies in which the mothers received prenatal care and a proper diagnosis of FGR, we would miss on an important percentage of subjects who had the social and economic risk factors we aimed to analyze. This limitation can be viewed as a potential strength due to the objective weight limit for each gestational age, ensuring that mistakes at inclusion were kept at a minimum.

We purposely excluded two significant socioeconomic risk factors from our analysis that could have given us further insight into this condition, alcohol consumption and marital status, due to potential misunderstandings and the societal stigma regarding both these issues, which could have prevented the interviewed women from giving honest answers.

The implications of our findings extend beyond the academic discourse, urging policymakers and healthcare providers to prioritize interventions that address socioeconomic inequities to reduce the burden of FGR. By understanding the manner in which these factors act, targeted strategies can be developed to mitigate their impact on fetal development.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest a compelling association between lower socioeconomic status and an increased likelihood of FGR. Maternal education and employment remain consistent predictors, with lower educational attainment and lack of a stable income linked to higher rates of FGR. Furthermore, environmental factors and lack of prenatal care exhibited significant correlations, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive approach to address the multifactorial nature of FGR.

There are definite improvements over the ten-year time span regarding certain socioeconomic factors, such as maternal employment and education, which resulted in an increase in prenatal care and a decrease in the rate of prematurity. Despite these dynamics, the overall prevalence of FGR remains high, meaning that economic and social factors are a minority of issues to be tackled regarding this condition. Smoking is still prevalent in mothers of SGA infants, and the percentage of teenage mothers of high-risk infants is concerning, at the least. This might represent a signal to healthcare policymakers to create campaigns aimed at deterring adolescents from drug/cigarette/vape use. Pregnancy-induced hypertension and obesity are also risk factors that may be changed with appropriate health policies concerning dietary habits and periodic check-ups at the primary healthcare provider.

Our research contributes to the evolving dialogue on the determinants of fetal growth restriction by providing a comprehensive analysis of the influence of socioeconomic factors in a hospital from the region with one of the largest prevalences of FGR in our country. Recognizing these associations and their trends is crucial for developing effective public health strategies aimed at reducing the incidence of FGR and improving maternal and child outcomes.

Source link

Mariana-Lăcrămioara Bucur-Grosu www.mdpi.com