1. Introduction

In human beings, the urinary system plays an important role in filtering blood by eliminating waste materials and extra water in the form of urine. The urinary system consists of several important organs like kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra. Urine is either sterile or has a very low concentration of pathogenic germs in healthy individuals, but for individuals with a higher concentration of pathogens, urinary tract infections prevail [

1]. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common bacterial ailment, affecting 150 million people annually and carrying a high risk of morbidity and expensive medical expenses. These infections can affect the urethra, the urinary bladder, or the kidneys. UTIs typically involve members of the

Enterobacteriaceae family, with

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli being the most common pathogen to be isolated [

2]. UTIs initiate when adhesins in the lower alimentary canal begin to nurture pathogens that gradually reach the urethra and then the urinary bladder. The bacteria start to develop and produce toxins and enzymes that help them counter the host’s inflammatory reaction to flush the toxins. Bacteria may develop from subsequent kidney colonization if the infection penetrates the kidney epithelial barrier.

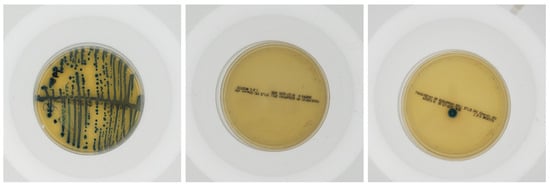

A urine culture tests urine samples for bacterial or fungal (yeast) infections, as identified and quantified by trained microbiologists. Now, this is a labor-intensive and time-consuming process, which is also prone to human error that often leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Over the last few decades, artificial intelligence has shown promising results thanks to the availability of large-scale datasets. Besides several interdisciplinary domains, artificial intelligence has revolutionized the fields of medical diagnosis, by recognizing certain critical features of importance. Convolutional neural networks (

CNNs) and other machine learning models inheriting the

CNN architecture have shown good validation accuracies in image recognition tasks, making them well suited for the analysis of medical images [

3]. The application of deep learning for the detection of bacterial growth in urine culture samples overrides a potential for faster, efficient diagnosis of UTIs. Traditionally, almost every machine (deep) learning model is built by inheriting the Multi-layered Perceptron (

MLP) architecture with a fixed activation function, which further varies the weights and biases of the network leading to the output, but recently, a state-of-the-art architecture—the Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (

KAN)—showed up, with variable activation functions in each edge of the graphical representation of the network. Several works [

4,

5] have inherited the

KAN architecture and have shown better results in many instances.

In recent years, numerous research have manifested the power of machine intelligence for medical diagnosis and experienced satisfactory results. Agrawal et al. contributed a Content-Based Medical Image Retrieval (CBMIR) system using deep neural models with transfer learning for lung disease detection using COVID-19 X-ray images, which resulted in an improvement in diagnostic metrics across subclasses in their research [

6]. Sheikh and Chachoo, in their research, introduced a class-wise dictionary learning approach for low-rank representation-based medical image classification improving robustness against noise by learning patterns for each class as tuples in the dictionary, addressing performance degradation caused by outliers in medical images. The model achieved good results based on its performance on the biomedical database [

7]. Asghari developed an IoT-based predictive model using smart wearable embedded systems for early colorectal cancer (CRC) detection in elderly patients, analyzing vital health indicators using machine learning methods in his research. The model achieved good results, especially in its implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic [

8]. Singh and Kumar, in their contribution, developed Inception network block (InDAENET)-integrated Denoising Autoencoders with an Inception network block to improve the quality of histopathological images of breast cancer. The proposed approach has been validated on the BreakHis dataset and is found to outperform traditional Denoising Autoencoder methods [

9]. Singh and Agarwal developed a novel convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture for the automated classification and segmentation of brain tumors from MRI images through their research. The proposed model was tested on contrast-enhanced T1 MRI images and achieved a classification accuracy of 92.50% using ten-fold cross-validation [

10]. Mahajan et al. contributed an ontology-based intelligent system for the prognosis of Myasthenia Gravis (MG) using ontology, semantic web rules, and reasoners to determine patient status (positive or negative) through their research [

11].

The diagnosis of microbial infections (like urinary tract infections) has traditionally relied on culture-based methods, biochemical assays, and molecular techniques—like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [

12], 16S rRNA sequencing [

13], and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) [

14]. These techniques often offer good specificity and therefore accurate identification of pathogens, but they require specialized equipment, trained personnel, and higher costs for their operation. Computer vision-based techniques can reduce the additional constraints of cost and equipment, and can assist expert supervision using machine intelligence. The specific advantages such techniques can offer are as follows: They can come up with rapid preliminary results, allowing molecular testing to focus only on clinically relevant cases, thus reducing stress on traditional techniques. It will enhance pathogen identification (overall) by combining phenotypic (culture-based) and genotypic (molecular-based) data. Additionally, such techniques are generally much more scalable; i.e., even in places where resources of traditional techniques do not exist, such techniques can be taken into account. Particular to molecular biology, multiple works have cited the improved accuracies and scalability of artificial intelligence (computer vision)-based techniques for the diagnosis of microbial infections. Goździkiewicz and her colleagues performed a review of AI-based techniques for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections [

15]. They reported that “AI models achieve a high performance in retrospective studies”. They further added that though technically relevant, computer vision is a comparatively new field, thus requiring further research. Shelke et al. identified the application of artificial intelligence to improve existing disease management, antibiotic resistance, epidemiological monitoring, etc. [

16]. They also reported faster, precise, and scalable applications. Further, Tsitou et al. reviewed the transformative impact of artificial intelligence on microbiology [

17]. They suggested the need of “interpretable AI models that align with medical and ethical standards” to digitalize the diagnosis of microbial infections. The need of the hour is therefore to integrate machine intelligence with expert knowledge, and therefore make the diagnostics much more affordable, reliable, scalable, and robust.

In this research, a dataset consisting of urine culture on Petri dishes as contributed by da Silva et al. [

18] is considered, and further, some deep learning models (e.g.,

ResNet-18,

DenseNet,

GoogLeNet, etc.) including a few state-of-the-art models (e.g.,

Class-Attention in Vision Transformers,

Vision Transformer, etc.) have been considered for the detection of bacterial growth in the urine samples. These models specifically inherit the

MLP architecture. As mentioned previously, a good number of studies reveal improved performance for several tasks using the architecture of Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks. Thus, a collection of three deep learning models inheriting the

KAN architecture is proposed—namely,

K2AN,

KAN-C-Norm, and

KAN-C-MLP. Experiments on the aforementioned urine culture dataset reveals

more accurate classification of UTI by the

KAN-based models than the state-of-the-art

MLP architecture-inheriting model. The contributions of this research can be summed up as follows: To the best of our knowledge,

this is the first work on the application of the Kolmogorov–Arnold Network or its variants on urology. Existing models (inheriting the

MLP architecture) were able to achieve a maximum of ≈

accuracy on the classification of urine culture samples, while the best of the three proposed models inheriting

KAN architecture—

KAN-C-MLP—achieved a validation accuracy of ≈

. Further, the proposed model is also computationally lightweight with very limited neural layers, suggesting much room for improvement in accuracy and scopes for further research.

The organization of the research is as follows:

Section 2 presents the dataset and its relevant details, along with the deep learning methodologies developed for this research.

Section 3 presents the results on a few well-known metrics. In

Section 4, we summarize the pros and cons of the proposed

KAN-based urine culture diagnostic system and finally the work is concluded in

Section 5.

5. Conclusions

Artificial intelligence and the large-scale availability of data have benefited many branches of sciences, technology, engineering, and management. Not only are the tasks supported by the higher accuracy of deep learning-based models, but also, they are time-efficient. Medical science has long been supported by the strong judgmental capabilities of medical professionals, but despite this, there are some false positives or false negatives, which affect the diagnosis process. Urine culture is performed in a clinical setting to identify the bacterial growth in one’s urine samples, which further fosters the diagnosis of UTIs. Studying urine samples requires expert supervision, and takes a considerable amount of time. This research suggested making use of deep learning-based image recognition techniques to effectively identify the presence of bacteria in one’s urine sample. Further, while the long-hailed Multi-Layered Perceptron architecture was able to detect UTI presence with an accuracy of nearly 80%, a state-of-the-art Kolmogorov–Arnold Network architecture was able to beat the accuracy benchmark and achieve an overwhelming accuracy of nearly 87%.

As addressed previously, a limitation of this proposed urine culture classification system is that it does not differentiate between bacterial species. For example, Staphylococcus epidermidis, a common skin commensal, is frequently isolated in urine cultures due to improper sample collection, which may result in false positives. In contrast, the presence of high CFU counts of uropathogenic Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Proteus mirabilis is clinically significant, but might be considered as a false negative. Thus, further research can be conducted by combining phenotypic colony recognition with molecular confirmation. This would make the diagnostic process much more reliable, scalable, and rapid.