1. Introduction

Over one third of global marine resources (37.7%) have been fished beyond sustainable levels [

1]. This decline in traditional fish stocks has prompted a search for alternative sources of seafood. As a result, interest in invertebrate fisheries has increased since the 1980s, and they have expanded rapidly over the past 3–4 decades [

2]. Invertebrate fisheries are an important contributor to the livelihood of many communities, providing food and income through their high value and expanding markets [

3]. Keeping up with global demand necessitates research to improve our estimations of invertebrate population biomass and for optimising the harvest strategies of aquacultural programs.

Standing stock estimation is a critical fisheries issue for the management of commercially important macroinvertebrates in the Pacific [

4]. Stock assessments provide managers with essential information on biomass, age and size composition, stock status in relation to target or reference points [

5] and support decision-making processes, often through projections and the application of harvest control rules [

6,

7].

Certain morphometric analyses allow the length and size class measurements of animals to be used to estimate body weights of animals and thus estimate overall biomass in wild populations [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Length measurements are easily obtained in the field, whereas weighing animals at sea can be difficult and imprecise. Certain studies might rely on length measurements of the sea cucumbers and later convert these to weights due to limited equipment [

13], or only measure body length for species unable to withstand the stress of being handled [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Some studies have even weighed the animals in the field and later converted these to estimates of body lengths [

18]. Determining the relationship of converting length to body weight (biomass) provides the ability to analyse marine communities and monitor fishery stocks, particularly when combined with data on length distributions and population densities [

19].

Allometric coefficients are derived from length–weight relationships, and relative changes in morphology are shown through the allometric growth equation (

y = axb, where

x is length,

y is weight,

a is the intercept, and

b is the allometric coefficient). Growth can be categorised as either isometric (

b = 3), where growth is proportional across the organism, or allometric (

b < 3 or

b > 3), which refers to differing growth rates in various body regions. These parameters offer insight into how increases in length relate to increase in weight, as well as the developmental adaptations that drive such relationships [

20]. Modelling length–weight data can provide calculations of condition indices and support the estimation of population biomass and life history parameters [

21]. Weight estimations are equally important in aquaculture to predict and improve harvest yields, optimise feeding, monitor the health status of animals, and improve economic efficiency [

22].

Sea cucumbers form an important multi-species fishery, sold as dried product, known as “bêche-de-mer” or “trepang” [

23]. Holothuroids are prone to overexploitation due to their high market value, ease of capture, late maturity, density-dependent reproduction, and low recruitment rates [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Marine resource managers and aquaculture professionals are increasingly interested in releasing aquaculture-reared animals into the wild for restocking, sea ranching and sea farming purposes [

28]. The practical feasibility and economic viability of sea ranching programs rely on integrating size–weight models—which help understand growth patterns and body proportions—with effective hatchery techniques, release strategies, and harvesting practices. This integration optimises stock management and improves the overall success of aquaculture programs [

28,

29]. Their economic viability also relies on the size at which the species can be harvested, for which, in most cases, knowledge and data are insufficient and there is a general lack of effective monitoring techniques [

30].

Accurate morphometric relationships are difficult to determine in holothuroids, as their body weight and dimensions are highly variable due to their body wall elasticity, the contents of the digestive system, and the contraction or relaxation of their muscles [

31,

32]. This variability can be addressed by using compound indices that combine different biometric parameters [

32,

33], allowing the calculation of body basal area and volume which can be utilised to generate more precise biometric relationships [

34,

35]. The use of composite indices based on the observed body length and width of sea cucumbers can enhance the accuracy of body weight estimations by 80% [

34]. Time out of water considerably affects the weight of the animal, with an average change of 31.93% within the first 10 min of exiting the water [

36,

37]. To minimise stress and prevent harm, previous studies have used in situ length measurements to avoid handling, as certain species may release Cuvierian tubules or even disintegrate entirely upon exposure [

17,

38,

39,

40]. However, ex situ measurements are preferred when animals are brought onboard for other purposes, such as weighing, or when in situ measurements are impractical due to the depth of the animals’ habitats [

32,

34,

41]. Comparison of in situ (underwater) and ex situ (out of water) data could provide insights into whether these data can be used interchangeably [

41]. Understanding the difference in length–weight relationships from measurements taken in situ vs. ex situ would permit a wide range of sea cucumber harvest data to contribute to future stock assessments and improve the accuracy of biomass estimation.

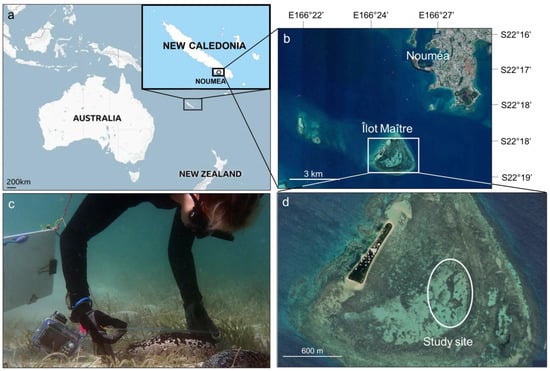

This study focused on

Holothuria lessoni, commonly known as the golden sandfish, previously referred to as

Holothuria scabra var.

versicolor [

42].

H. lessoni is one of the most valuable tropical sea cucumber species in the dried seafood market, averaging USD 503 per kg, dried, on the Hong Kong retail markets (2022) [

43]. They are distributed throughout the tropical Indian and Western Pacific Oceans from Kenya to as far east as Tonga [

42]. The average length of

H. lessoni is 30 cm, and average adult weight is 1400 g [

44]. The golden sandfish is considered to have high potential for aquaculture as they are highly suitable for hatchery production. This is due to their low risk of disease, adaptability to a range of environments, and readiness to harvest in as short as 12 months after release [

45]. Three colour morphs are conspecific with this species—black, beige, and blotchy—and it can be found living sympatrically with its closely related congener

H. scabra [

46]. This study focused solely on the blotchy variant of

H. lessoni.

We aim to fill critical knowledge gaps on H. lessoni for future population assessments and conservation, addressing morphological relationships. Length–weight relationships and biometric relationships are assessed and compared between in situ and ex situ measurements to determine if one is more reliable. We also compare the change in length–weight relationships of H. lessoni with that of two previous studies conducted at the same site.

3. Results

The body weight (

W) of

H. lessoni (

n = 77) averaged (mean) 1774 g (±372 g SD). Upon being handled, the sea cucumbers contracted, reducing their length while concomitantly increasing body width. Within the first minute aboard the vessel, they began to relax, gradually flattening on the deck, becoming noticeably wider and longer (

Figure 2). After 5 min, the animals had expelled water from their bodies and often flattened completely on the deck, resulting in a noticeable increase in body dimensions. Paired

t-tests showed that body length (

L) measurements provided significantly different (

p < 0.001) averages when measured in situ (26 cm ± 4.9 cm SD) compared to ex situ (28 ± 3.3 cm SD) as well as body width (

p < 0.001) with a mean of 11 cm (±1.1 cm SD) in situ and 12 cm (±1.5 cm SD) ex situ. Length frequency distributions were unimodal (

Figure 2) and ranged from 17 to 39 cm, and weight frequency had an asymmetric distribution ranging from 1010 to 3070 g.

All metrics of body size offered a better fitting relationship with body weight when based off in situ measurements (

Figure 3). The ex situ data generated

R2 values for the size–weight relationship that were 6–12% lower, indicating less reliability compared to the in situ data.

Overall, the biometric measurements

SLW (square root of the length–width product) and

Le (recalculated length) with data from in situ demonstrated the strongest relationship with weight (

R2 = 0.576;

Table 1). The high RMSE values (≥242) indicate a relatively poor fit for each metric’s relationship with weight.

Comparing the size–weight relationships for in situ and ex situ measurements, each metric (L, BBA, Le and SLW) revealed that underwater measurements differ significantly (p < 0.001) from those taken out of the water. The size–weight relationship varies considerably depending on whether the data are from animals measured underwater (unmanipulated) or on the vessel (post handling), with better estimates of weight based on in situ data.

On average,

H. lessoni have reduced in length and increment in weight at Îlot Maître (

Figure 4) when compared to that of previous studies [

51,

52]. The longest body measurement was taken in the 1989 study (46.9 cm), and the heaviest animal was recorded in the present study, weighing 3070 g.

Comparison of regression models among studies at Îlot Maître demonstrated that length measurements for

H. lessoni provide a weak estimate of weight (

R2 < 0.6 for each study). Length–weight relationships were significantly different (

p < 0.05) between each study (

Table 2). The average length of the animals has decreased from Conand’s study in the 1980s [

51] to the research conducted by Purcell et al. in 2007 and 2008 [

52] and further to the present study. Across the three studies, mean body length decreased from 34.8 cm to 27.6 cm. The Fulton’s coefficient condition factor (

K) for

H. lessoni at Îlot Maître was 3.51 ± 1.4 in the initial study conducted in 1989 [

51]. This has increased more than two-fold in the present study, rising to 8.67 ± 2.7 in 2024.

4. Discussion

Îlot Maître was designated as a marine reserve in 2002 to protect the lagoon ecosystem [

48]. The increase in Fulton’s condition factor (

K) for

Holothuria lessoni over time could indicate an improvement in the condition of animals at this site. The condition factor rose from 3.51 (±1.4 SD) in 1989 [

51] to 4.94 (±0.9 SD) in 2009 [

52], reaching 8.67 (±2.7 SD) in the present study (2024) at the same site. In contrast, a recent study across Indonesia found that the condition factors of

H. lessoni ranged from 1.37 to 6.09. Additionally, the average length of the population in Indonesian waters was 13.1 cm (±5.7 SD), less than half the length of those at Îlot Maître (27.6 ± 3.3 cm), and their average weight was 102 g (±92 SD), over 15 times lighter. The collection of data on current population densities was beyond the scope of the study, so it is difficult to draw implications about the success of this marine reserve.

Successful fisheries management relies on accurate stock assessments to implement effective harvest strategies. Previous research [

36,

41] has shown there is a significant difference between the initial weight of the animal and the weight of the animal once all the water has been expelled, with measurements varying substantially even after a brief five-minute draining period [

37]. Our data indicate that length and width measurements taken in situ (underwater) and ex situ (out of the water) also yield significantly different relationships. Therefore, to minimise any discrepancies, these data should not be used interchangeably. After measuring the animals in situ, they typically contract upon initial handling. Once removed from the water and measured ex situ, they would then flatten out over time, resulting in an increase in length and width. These changes in measurements can greatly alter the length–weight relationship. A consistent method for stock assessments is critical to generate reliable estimates of animal weights and estimations of population biomass. Consistency and reliability in biomass estimation methods are especially important in aquaculture, as they enable managers to optimise daily feeding, control stocking densities, and determine the optimal time for harvesting [

55]. This appears to be best achieved by taking length and width measurements underwater before any manipulation of the animals.

Due to the plastic nature of sea cucumbers, the bidimensional indices of body basal area,

SLW, and

Le provided us with alternative body size metrics for length–weight analyses. Among these,

SLW and

Le offered the most reliable estimates of weight. This has also been found for other holothuroids such as

Isostichopus badionotus [

34] and

Pearsonothuria graeffei [

56].

In situ measurements yielded significantly different relationships with weight compared to ex situ measurements across all body size metrics. Specifically, in situ measurements provided more reliable estimates of weight (

R2 = 0.58) compared to ex situ data (

R2 = 0.45). Despite these improved estimates, our data produced relatively weak size–weight relationships compared to those reported in previous studies [

56,

57]. This weak relationship has been linked to taxa with highly variable water content [

19] and may also reflect variable morphology among individuals. Additionally, obtaining accurate weight measurements in the field proved challenging on windy days, as the hanging balance was not as easy to keep stable. Even weaker size–weight relationships have been found for other holothuroids, including

Holothuria whitmaei and

Pearsonothuria graeffei [

56,

58]. While sample size in this study is consistent with those used in size–weight studies on other holothuroids [

52,

57,

59,

60], the variability in the size–weight relationship found in our study on

H. lessoni is considerable. Greater variability has been observed in studies of other holothuroid species, even with larger sample sizes [

53,

56,

58,

61]. Nonetheless, the low

R-squared values in this study indicate that these relationships should be applied cautiously. Further research on this species should aim to include much larger sample sizes to improve confidence in the size–weight relationships. Our findings align with prior suggestions [

31,

34,

35] that future stock assessments of sea cucumbers should be done using biometric indices that combine length and width rather than using observed body length alone, as done for fin fish.

Evaluating the length–weight relationship of cultured aquatic animals is a common way to assess their general health condition [

62]. However, sea cucumbers exhibit large individual variability due to their water retention capacity and variable body shapes among individuals. The multiple non-linear regression analyses across studies suggest significant changes in length–weight relationships over time, indicating the need for regular updates within fisheries to ensure accurate weight estimations. These variations may be influenced by factors such as the time of year when data are collected, as animal sizes may fluctuate with reproduction and spawning cycles. Differences in sampling methods across studies further emphasise the importance of adopting standardised approaches. Additionally, location appears to have a significant influence on these relationships [

63]. As previously noted, such variability is inherent to most sea cucumbers [

34,

61,

64]. Therefore, it may be beneficial for fisheries and aquaculture programs to re-evaluate the length–weight models regularly using a considerably large sample size.

This is the first study to examine changes in the morphology of sea cucumbers over decades. We recognise that this study was done in only one month of the year and does not examine potential seasonal variations that could exist in size–weight relationships of the population. However, the observed shifts in length–weight relationships indicate morphological changes in individuals within a species over time, potentially influenced by climatic or environmental factors. New Caledonia experiences a wet season, during which cyclones and tropical storms are relatively frequent. Notably, our study site (Îlot Maître) has eroded by 10.5% between 1935 and 2014 [

65], which may impact these populations. This could in turn be due to climate change, resulting in increasing rainfall, wind, and currents. Additionally, the biological changes observed in

H. lessoni may be attributed to climate change, as it affects food availability, sediment and substrate types, distributions, and habitat chemistries [

66].

Our findings highlight the need for applying some best-practice analytical methods for estimating sea cucumber populations. This is especially true for the heavily exploited species that have experienced marked declines in population abundance. The success of the marine reserve at Îlot Maître demonstrates that well-implemented strategies can significantly bolster the health of vulnerable species like H. lessoni. To build on this success, it is essential for stock assessments to employ accurate and consistent measurement methods. Here, we provide key recommendations based off our results to improve biomass estimates for fishery harvest strategies:

For this species, and likely others, use in situ (underwater) length and width measurements to estimate the size of the sea cucumbers.

Avoid using size–weight relationships from in situ data to estimate body weight from length and width measurements made ex situ, and vice versa.

Collect data for size–weight relationships from a large sample of individuals (e.g., >100).

For estimating body weight, use biometric indices such as SLW and Le rather than body length.

Re-evaluate length–weight relationships within a fishery at regular intervals or if methodologies are adapted to ensure accuracy.

Integrating these measures will improve our estimation of sea cucumber populations. Further work on in situ and ex situ morphometric relationships of other harvested species is needed to provide fisheries with accurate tools for stock assessments.