When an enormous 8.8 magnitude earthquake struck near Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, the impact reached far beyond its epicenter. In the passing hours, tsunami alerts were issued by several nations with coastlines along the Pacific Ocean’s Ring of Fire, prompting evacuations and escalating emergency response efforts from Japan to Hawaii and along the U.S. West Coast. Due to a number of geological factors, this disaster did not result in significant damage or loss of life. That said, it served as a powerful reminder that in the face of rapidly moving natural hazards, the primary defense is time, and the systems that give us a chance to act before time runs out.

Tsunamis are rare, but potentially high-impact events. They can travel across ocean waters at speeds up to 500 mph, with surging seawater often crashing into densely inhabited areas. A series of massive waves striking during the night can be particularly devastating, as coastal communities are often caught off guard. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2011 Japan tsunami were two of the most ruinous natural disasters in recent history, claiming over 230,000 lives across 14 countries in the former, and more than 18,000 lives in Japan alone during the latter.

Due to this extreme risk, tsunami early warning systems are a necessity. They provide immediate warnings and educate communities on safety measures. However, the general public’s receptiveness to the messaging is just as important as the given communication technology. Whether it’s a loud siren or a cell phone text message, a warning won’t add value if people don’t understand it or know what to do in the next few minutes.

Tsunami Early Warning Systems

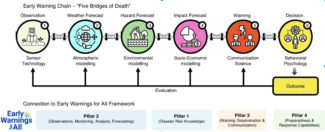

An effective tsunami early warning system begins with detection. Seismic networks identify submarine earthquakes, whereas ocean sensors—such as DART buoys (Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis) and tide gauges—measure changes in sea level. These data are then analyzed by organizations such as the U.S. Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), which determine the probability and potential severity of a tsunami and then disseminate alerts.

After sensor detection, the impact is modeled using various environmental and socio-economic forecasting methods, to anticipate potential direct or indirect effects.

The most formidable challenges, however, pertain to communication. Alerts need to go out rapidly and clearly using radio, TV, text messages, sirens and social media. These alerts usually tell people when the first waves will strike, which places are most at risk and what residents should do to stay safe. The “last mile” of communication, often considered the vital, final step of making sure that persons at risk receive these notifications, is one of the most enduring problems.

Gaps with Tsunami Warning Systems

As tsunami waves strike a coastline, an immediate evacuation to higher ground is critical, especially for rural or impoverished communities. And it is in these communities where various warning system gaps are most apparent. Infrastructure may be inadequate, government-led messaging may not be trusted, and language barriers may impede comprehension. Even the most accurate notifications may not save lives if efforts are not made to address these problems.

A lack of public awareness can also be another crucial weakness. In certain places, individuals are unaware of the meaning of the various warning levels or what to do in the event of an alert. Confusion or inaction may result from inaccurate information, exaggerated previous warnings, or a lack of community involvement in preparedness initiatives. In a similar vein, warning systems and local emergency response plans are not always shared widely. The entire response effort may fail when it is most needed if schools, health facilities, and community organizations do not actively participate in planning and exercises.

Challenges further persist due to technological and logistical shortcomings. In some areas, real-time monitoring systems are either missing or rely on outdated technology that may fail during power outages or severe weather events. Difficult terrain and limited road access can also make evacuations more difficult. Additionally, in many nations, consistent funding remains a major hurdle. Early warning systems are frequently dependent on NGO support rather than being included in national budgets, making them prone to underinvestment and eventual deterioration.

Highly Developed Tsunami Warning Protocols

Countries such as Japan have developed new ways to incorporate early warning systems into national policy and community preparedness. Japan’s tried-and-true system combines instantaneous seismic monitoring with public outreach, clearly marked evacuation routes, and regular drills that reinforce routine, life-saving behaviors. Students in K-12 schools routinely practice evacuation procedures, with substantial time devoted to disaster preparedness in the public school curriculum. Interactive geographic information system phone apps are readily accessible, and residents actively participate in trainings, with an awareness that tsunamis are an inevitable threat.

Chile has also made considerable progress, especially following the calamitous 2010 earthquake and tsunami. The country has increased training exercises and intercommunication between national and local agencies, assuring that warnings lead directly to coordinated, effective action in previously neglected areas. In Indonesia, the staggering loss of life from the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami triggered the development of a regional alert system, supported by international partners. This effort has enhanced an understanding of the risks and associated preparedness strategies needed for transformational change.

The U.S. Pacific Tsunami Warning Center serves as a model for international cooperation. By coordinating alerts among dozens of countries across the region, it ensures that warnings are not confined by national borders.

The literature on tsunami evacuations also notes that communities with strong social capital and robust social networks are usually more prepared to engage in evacuation protocols, with substantial efforts to reach highly vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly and the disabled.

The Potential to Save Lives

Ultimately, tsunami early warning systems save lives not just when they are fast or accurate, but when they are trusted, understood and acted upon. This requires more than just technology: There is also a need for training, investment and coordination with the public and private sector. Regular drills ensure that when the sirens sound or the text messages arrive, people know exactly what to do. Such efforts turn conceptual awareness into real-world readiness.

Although tsunamis occur infrequently, their impact can be catastrophic. Enhancing early warning systems must go beyond a reaction to past disasters to instead consider future risks. There should be a continuous and proactive global commitment that acknowledges our collective vulnerability and mutual responsibility to safeguard lives.

Thomas Chandler, Ph.D., is the managing director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness (NCDP) as well as an associate member of the Columbia Climate School faculty. He focuses on post-disaster housing and economic recovery, mass care community sheltering and relocation assistance, pandemic preparedness and response, rural and Tribal Nations readiness and resilience, geographic and social networks, and community preparedness. He is the director of NCDP’s FEMA training program.

Hannah Dancy is a project coordinator at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness (NCDP), where she supports the planning and implementation of FEMA training grant-based courses. She holds a Master of Arts in Ecology, Environmental and Conservation Biology from Columbia University. She is interested in the intersection of climate and environmental change with disaster preparedness, and how we can use effective science communication to prepare communities for these disasters.

Source link

Guest news.climate.columbia.edu