1. Introduction

Wave power (WP) has essential strategic value in remote seas where laying power grids is costly. By utilizing the vast and largely untapped energy from ocean waves, WP can reduce reliance on traditional fossil fuels and provide a reliable and continuous power supply [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It can offer green energy for observation equipment, oil drilling platforms, ranches, and other offshore facilities. For example, WP can supplement the energy requirements of remote islands [

6,

7], where conventional energy infrastructure is often challenging to establish and maintain.

It is necessary to carry out systematic resource assessments before planning WP deployment projects and designing the wave energy converters [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Take the South China Sea (SCS), the largest marginal sea in the western Pacific, as an example; due to its unique geographical characteristics and rich marine resources, many studies have been performed to assess the richness and stability of WP resources, based on in situ observations, satellite data, and numerical models [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. For example, numerical models reveal that the WP is richest in the northern deep basin area of the SCS [

8,

11,

12]. Meanwhile, it can be influenced by shallow topography such as islands [

6,

12,

13,

15] and coastal regions [

6,

9,

10,

14,

16]. As a result, the WP exhibits significant seasonal and regional variations under the combined effects of seasonal winds and shallow topography in the SCS, e.g., [

14,

15].

Because WP is a strategic oceanic resource, accessing the long-term development trends is particularly important. Therefore, recent studies have increasingly paid more attention to the long-term variations and their forcing driving mechanisms in the WP assessment studies for the SCS [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. For example, Ching-Piao et al. quantitatively evaluated the variations in wave climate in the northwestern Pacific and Taiwan waters based on a long-term wave dataset [

17]. Zheng et al. proposed that the China Seas exhibited a significant overall increasing trend in WP density for several decades, mainly before 2011 [

18,

19,

20]. They point out that the rising trend in winter and spring is more substantial than that in summer and autumn in the SCS [

18]. Sun et al. focused on the WP trend in the coastal regions of the China Seas, and their results emphasize the significantly increasing trend in the northern coastal SCS during winter [

21,

22]. Liu et al. evaluated the long-term variability in global WP and demonstrated the increasing WP results from the global climate change and intensification of the Antarctic Oscillation [

23]. Although the existing studies have greatly enhanced our understanding of long-term characteristics and distribution patterns for the WP in the SCS, most of the analysis focuses on a monotonic trend within a limited period. Previous studies have pointed out that a WP peak appeared in 2011 for the SCS (e.g., [

18,

19]); however, the long-term trend after this peak, especially its difference compared to the trend before 2011, has still received limited attention.

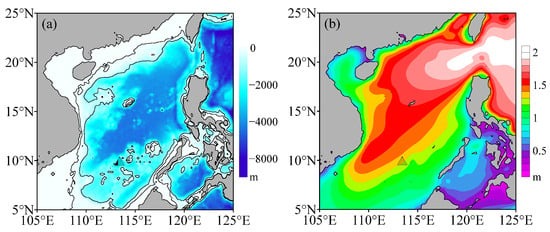

Moreover, clarifying the driving factors behind the trends will help us understand the variation mechanism and further predict WP. The SCS has a complex topography [

24] and a unique oceanographic environment [

25], and the factors affecting WP variation should be comprehensively considered. Previous studies have shown that the seasonal distribution of and variation in the wind field are the main driving forces that cause the variance of waves and WP. For example, Zheng et al. conducted a regionalization analysis of wind and wave energy resources in the East China Sea and the SCS [

26]; Wang et al. assessed wave and wind energy in the Weifang Sea area over 20 years [

27]; Dong et al. simulated the wind and wave energy resources in the waters off the Yangtze River Delta [

28]. Their results reveal a close relationship between wind and wave energy. However, for the SCS, in addition to wind forcing, the modulation of environmental factors such as topography and background swells on the WP may also need to be considered. This is because, although the direction of wind and waves changes seasonally with the monsoon, the swell energy from the deep ocean that propagates from the northeast to the southwest throughout the year always dominates [

15,

29]; in addition, complex topographic factors have a significant impact on the wave dynamics and energy in local areas [

12,

13].

Based on the above considerations, this study extends the WP long-term trend analysis to the most recent year. It systematically analyzes the spatial and seasonal distribution characteristics of the trend in the SCS from 1979 to 2024. The study focuses on the differences between the trends before and after 2011. Based on the results of the WP’s long-term trend, the driving mechanisms of the trend are discussed in relation to the wind field’s contemporary variations. Background environmental factors such as topography and swell are combined into the discussion for the situations where trends in WP and winds are not entirely consistent.

5. Conclusions

Based on the ERA5 (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis v5) reanalysis data for 45 consecutive years from 1979 to 2024, this study systematically evaluates the interannual variation trend in wave power (WP) in the South China Sea (SCS). Based on the wind field data, the driving mechanism of the long-term WP trend is further discussed. The results can be summarized as the following points of conclusions.

(1) Although the WP experienced a general, long-term, increasing trend from 1979 to 2024, there was a remarkable turning point in 2011. Before 2011, the WP mainly exhibited an increasing trend, but such a trend reversed after 2011.

(2) The WP trend has remarkable seasonal and spatial variation characteristics. Seasonally, the trends in winter and spring are consistent, while the trends in summer and autumn are inconsistent with the annual trend. Spatially, the high-value area of the trend mainly extends from the northeast to the southwest over the deep basin.

(3) The variations in wind fields are the direct forcing factor leading to the long-term variation in WP. Meanwhile, the background swells propagating from the Western Pacific and the local shallow topography can also play essential roles in the modulation of the WP’s variation trend.

This study contributes to the continuously updated research on wave energy resources and their long-term trends in the SCS by extending the trend analysis to the most recent year. The results emphasize the opposite long-term trend in WP before and after 2011, and the mechanism can be related to coupled effects combining dynamic and environmental factors. However, our study still has limitations regarding the mechanisms by which global climate change affects wind fields and swells. Therefore, the complexity of the long-term variation in WP should be fully considered, and the mechanism for the variations still needs to be further clarified in future studies.