In the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, Justin Bibb was living in a tight, one-bedroom apartment in Cleveland, Ohio. He couldn’t open his windows because his home was an old office building converted to residential units — not exactly conducive to physical and mental well-being in the middle of a global crisis. So he sought refuge elsewhere: a large green space, down near the lakefront, that he could stroll to.

“Unfortunately,” Bibb said, “that’s not the case for many of our residents in the city of Cleveland.”

A native of Cleveland, Bibb was elected the 58th mayor of the city in 2021. Immediately after taking office, he took inspiration from the “15-minute city” concept of urban design, an idea that envisions people reaching their daily necessities — work, grocery stores, pharmacies — within 15 minutes by walking, biking, or taking public transit. That reduces dependence on cars, and also slashes carbon emissions and air pollution. In Cleveland, Bibb’s goal is to put all residents within a 10-minute walk of a green space by the year 2045, by converting abandoned lots to parks and other efforts.

Cleveland is far from alone in its quest to adapt to a warming climate. As American cities have grown in size and population and gotten hotter, they — not the federal government — have become crucibles for climate action: Cities are electrifying their public transportation, forcing builders to make structures more energy efficient, and encouraging rooftop solar. Together with ambitious state governments, hundreds of cities large and small are pursuing climate action plans — documents that lay out how they will reduce emissions and adapt to extreme weather — with or without support from the feds. Cleveland’s plan, for instance, calls for all its commercial and residential buildings to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

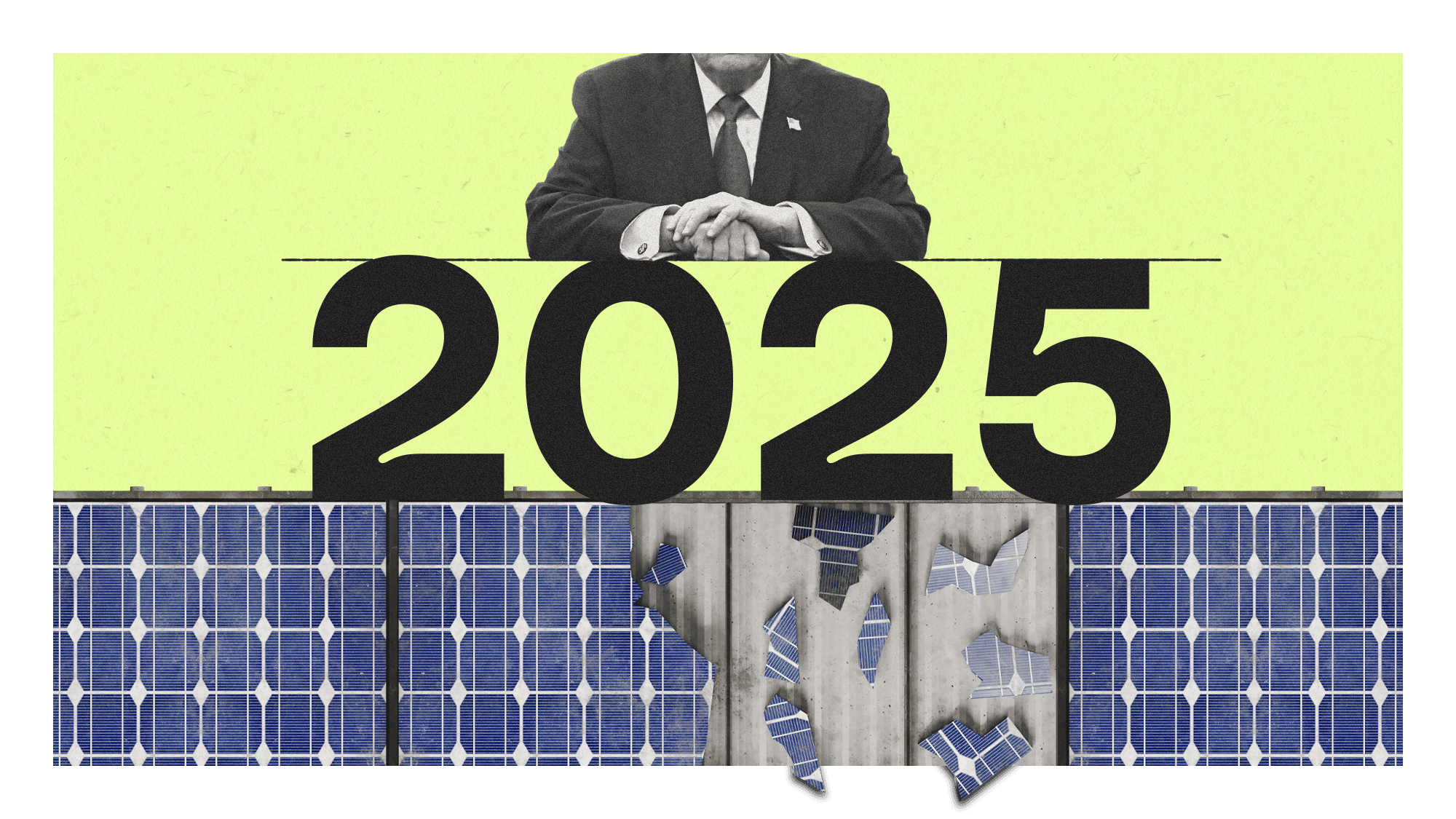

For local leaders, climate action has grown all the more urgent since the Trump administration has been boosting fossil fuels and threatening to sue states to roll back environmental regulations. Last week, Republicans in the House passed a budget bill that would end nearly all the clean energy tax credits from the Biden administration’s signature climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act. “Because Donald Trump is in the White House again, it’s going to be up to mayors and governors to really enact and sustain the momentum around addressing climate change at the local level,” said Bibb, who formerly chaired Climate Mayors, a bipartisan group of nearly 350 mayors.

City leaders can move much faster than federal agencies, and are more in-tune with what their people actually want, experts said. “They’re on the ground and they’re hearing from their residents every day, so they have a really good sense of what the priorities are,” said Kate Johnson, regional director for North America at C40 Cities, a global network of nearly 100 mayors fighting climate change. “You see climate action really grounded in the types of things that are going to help people.”

Dustin Franz for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Shifting from a reliance on fossil fuels to clean energy isn’t just about reducing a city’s carbon emissions, but about creating jobs and saving money — a tangible argument that mayors can make to their people. Bibb said a pilot program in Cleveland that helped low- to moderate-income households get access to free solar panels ended up reducing their utility bills by 60 percent. The biggest concern for Americans right now isn’t climate change, Bibb added. “It’s the cost of living, and so we have to marry these two things together,” he said. “I think mayors are in a very unique position to do that.”

To further reduce costs and emissions, cities like Seattle and Washington, D.C. are scrambling to better insulate structures, especially affordable housing, by installing double-paned windows and better insulation. In Boston last year, the city government started an Equitable Emissions Investment Fund, which awards money for projects that make buildings more efficient or add solar panels to their roofs. “We are in a climate where energy efficiency remains the number one thing that we can do,” said Oliver Sellers-Garcia, commissioner of the environment and Green New Deal director in the Boston government. “And there are so many other comfort and health benefits from being in an efficient, all-electric environment.”

To that end, cities are deploying loads of heat pumps, hyper-efficient appliances that warm and cool a space. New York City, for instance, is spending $70 million to install 30,000 of the appliances in its public housing. The ultimate goal is to have as many heat pumps as possible running in energy-efficient homes — along with replacing gas stoves with induction ranges — and drawing electricity from renewables.

Metropolises like Los Angeles and Pittsburgh are creating new green spaces, which reduce urban temperatures and soak up rainwater to prevent flooding. A park is a prime example of “multisolving”: one intervention that fixes a bunch of problems at once. Another is deploying electric vehicle chargers in underserved neighborhoods, as Cleveland is doing, and making their use free for residents. This encourages the adoption of those vehicles, which reduces carbon emissions and air pollution. That, in turn, improves public health in those neighborhoods, which tend to have a higher burden of pollution than richer areas.

Elizabeth Sawin, director of the Multisolving Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, said that these efforts will be more important than ever as the Trump administration cuts funding for health programs. “If health care for poor children is going to be depleted — with, say, Medicaid under threat — cities can’t totally fix that,” Sawin said. “But if they can get cleaner air in cities, they can at least have fewer kids who are struggling from asthma attacks and other respiratory illnesses.”

All this work — building parks, installing solar panels, weatherizing buildings — creates jobs, both within a city and in surrounding rural areas. Construction workers commute in, while urban farms tap rural growers for their expertise. And as a city gets more of its power from renewables, it can benefit counties far away: The largest solar facility east of the Mississippi River just came online in downstate Illinois, providing so much electricity to Chicago that the city’s 400 municipal buildings now run entirely on renewable power. “The economic benefits and the jobs aren’t just necessarily accruing to the cities — which might be seen as big blue cities,” Johnson said. “They’re buying their electric school buses from factories in West Virginia, and they’re building solar and wind projects in rural areas.”

So cities aren’t just preparing themselves for a warmer future, but helping accelerate a transition to renewables and spreading economic benefits across the American landscape. “We as elected officials have to do a better job of articulating how this important part of public policy is connected to the everyday lived experience,” Bibb said. “Unfortunately, my party has done a bad job of that. But I think as mayors, we are well positioned to make that case at the local level.”

Source link

Matt Simon grist.org