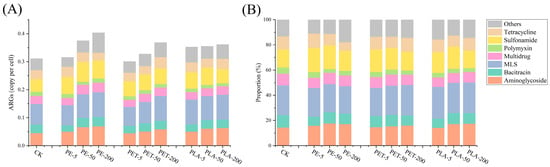

3.1. The Effects of MPs on ARG Abundances

Metagenomic analysis was conducted to comprehensively explore the impact of PE, PET, and PLA-MPs on the abundance of ARGs throughout the AD process of SS. A total of 26 types of ARGs were detected within the AD system. Among these, macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin (MLS), aminoglycoside, bacitracin, multidrug, polymyxin, sulfonamide, and tetracycline resistance genes were identified as the predominant ARG types (Figure 1). Exposure to PE, PET, and PLA resulted in significant increases in the relative abundance of ARGs at varying levels compared to the control without MPs (one-way ANOVA, F = 23.257, p < 0.05), with a general trend of increased total ARG abundance correlating with higher concentrations of these MPs, particularly at 200 mg/L for PE and PET. In the control group, the total relative abundance of ARGs was 0.311 copies per cell. Under PE exposure, the total relative abundance of ARGs increased to 0.316 copies per cell at 5 mg/L, 0.375 copies per cell at 50 mg/L, and 0.404 copies per cell at 200 mg/L, marking a maximum increase of 29.90%. Under PET exposure, the total abundance of ARGs decreased to 0.301 copies per cell at 5 mg/L but rose to 0.328 copies per cell at 50 mg/L and 0.369 copies per cell at 200 mg/L, achieving a maximum increase of 18.64%. Under PLA exposure, the total relative abundance of ARGs increased to 0.362 copies per cell at 5 mg/L, decreased to 0.355 copies per cell at 50 mg/L, and further to 0.353 copies per cell at 200 mg/L, with a maximum increase of 14.15%. Similar results indicated that Zhang et al. found the relative abundance of eARGs of the eight tests was 1.70 times and 2.15 times that of the control group, respectively, with the exposure of microplastic fibers during sludge anaerobic digestion [34]. Luo et al. found that compared with the control group, the MPs with ARGs abundance in the range of 10~80 particles/g-TS were dose-dependent, and the relative abundance of ARGs increased by 4.5~27.9% [35].

Overall, while individual types of ARGs experienced declines under the exposure to PE, PET, and PLA-MPs, there was a general increase in the total relative abundance of ARGs, with PE exposure resulting in significant higher relative increase compared to PET and PLA (p < 0.05). Relative to the control, the addition of these three types of MPs promoted the proliferation of MLS, aminoglycoside, and sulfonamide resistance genes yet exerted an inhibitory effect on polymyxin resistance genes. Metagenomic sequencing offers a comprehensive tool for delineating the spectrum of ARGs during the AD process. MLS resistance genes confer bacterial resistance to MLS antibiotics, a class commonly used to treat a variety of infections including respiratory, skin, and soft tissue infections. Resistance is mediated through multiple mechanisms, including drug efflux, target modification, and enzyme-mediated drug degradation [36]. Aminoglycosides are a broadly utilized class of antibiotics, encompassing drugs such as gentamicin, kanamycin, and amikacin. Aminoglycoside resistance genes enable bacteria to resist these drugs through several mechanisms, including enzyme-mediated drug modification (e.g., phosphorylation, acetylation, or adenylation), drug efflux, and target modification [37]. Sulfonamides are another widely used class of antibiotics, primarily for treating bacterial infections such as urinary and respiratory tract infections. Sulfonamide resistance genes primarily operate by encoding alterations in the antibiotic target dihydropteroate synthase, rendering it insensitive to sulfonamide drugs, or by enhancing the bacterial utilization of environmental folate, thereby circumventing drug inhibition. These genes, such as sul1, sul2, and sul3, are typically located on bacterial plasmids, facilitating their propagation among different bacterial species through HGT [38]. These three types of ARGs are commonly detected in the environment, particularly in hospital wastewater, livestock wastewater, and urban sewage. This prevalence is largely due to the extensive use of aminoglycosides, macrolides, lincosamides, streptogramins, and sulfonamides, incomplete drug metabolism, and insufficient waste treatment systems, which contribute to the widespread distribution and propagation of these ARGs across various environments. The presence and dissemination of these ARGs heighten the proportion of multidrug-resistant bacterial strains in the environment, necessitating enhanced monitoring of these ARG types to assess their spread and ecological impact.

In all samples analyzed, 429 subtypes of ARGs were detected, with 22 of these ARGs exhibiting a relative abundance exceeding 0.001 copies per cell (Figure 2). Among the detected ARGs, the sulfonamide resistance gene sul1 showed the highest relative abundance, followed by the bacitracin resistance gene bacA, the MLS resistance gene ermG, another sulfonamide resistance gene sul2, and the MLS resistance gene mel. The resistance mechanisms associated with these ARG subtypes primarily involve antibiotic inactivation, antibiotic efflux, antibiotic target protection, antibiotic target alteration, and antibiotic target replacement. Notably, sul1 demonstrated significant proliferation across various AD systems. Under exposure to PE-MPs, the relative abundance of sul1 increased from 0.0182 copies per cell to 0.0277 copies per cell at 50 mg/L PE-MPs and to 0.0297 copies per cell at 200 mg/L PE-MPs. Under PET-MPs exposure, the relative abundance of sul1 rose to 0.2414 copies per cell at 5 mg/L PET-MPs, 0.0217 copies per cell at 50 mg/L PET-MPs, and 0.0190 copies per cell at 200 mg/L PET-MPs. Under PLA-MPs exposure, the relative abundance of sul1 increased to 0.0196 copies per cell at 5 mg/L PLA-MPs, 0.0222 copies per cell at 50 mg/L PLA-MPs, and 0.0245 copies per cell at 200 mg/L PLA-MPs. The sul1 gene is frequently found in integrons, particularly in those associated with multidrug-resistant bacteria in hospitals and communities. Within integrons, the sul1 is often located at the end of gene cassettes, which facilitates its stability and propagation [39]. This suggests that MPs exposure under AD conditions enhances the abundance of MGEs, particularly integrons. Furthermore, the presence of sul1 not only confers resistance to sulfonamide antibiotics but may also facilitate the co-transmission of other ARGs, thereby increasing bacterial capacity for multidrug resistance. Additionally, due to its high mobility and pathogenicity, bacA is classified as a high-risk ARG (Category 1) [40]. Under exposure to PE-MPs, the relative abundance of bacA increased by 0.30% at 50 mg/L PE-MPs and by 3.29% at 200 mg/L PE-MPs while showing a decreasing trend under PET and PLA-MPs exposure. Overall, prolonged exposure to MPs, particularly at higher concentrations, promotes the generation and propagation of ARGs, accompanying an elevated risk of ARG proliferation and dissemination.

3.2. The Effects of MPs on MGE Abundances

HGT among microorganisms can be facilitated by MGEs such as integrons, transposons, and plasmids, which significantly contribute to the dissemination of ARGs [41]. MGEs serve as crucial indicators for monitoring the lateral transfer of ARGs and are employed in various environments to confirm the capability of ARGs to transfer horizontally [42]. Through alignment with an MGEs database, a total of 263 subtypes of integrons, 87 subtypes of ICEs, 4833 subtypes of plasmids, and 164 subtypes of transposons were annotated (Figure 3). In different AD systems, plasmids exhibited the highest relative abundance among MGEs, followed by transposons, while integrons and ICEs showed lower relative abundances. Furthermore, exposure to various MPs also significantly increased the relative abundance of MGEs within AD systems (one-way ANOVA, F = 43.524, p < 0.05). Under exposure to PE and PET-MPs, the relative abundance of MGEs gradually increased with the level of exposure than PLA-MPs, suggesting that PE and PET-MPs may facilitate the increase in MGEs within microbial communities through physical impacts or the release of chemical substances, potentially exacerbating the spread of ARGs. This phenomenon may be related to the chemical properties of the MP surfaces or the microbial adhesion capabilities, as MP surfaces might provide a new ecological niche for microorganisms, thereby influencing their genetic structure. In contrast, exposure to PLA-MPs did not lead to an increase in the relative abundance of MGEs, even with increased PLA concentrations. This may be due to the biodegradable nature of PLA, which does not persist in the environment as long as PE and PET, thus exerting less impact on microbial communities. Additionally, PLA may not facilitate the propagation of MGEs, potentially related to its physical structure or the nature of microbial interactions with PLA [43].

The dissemination of ARGs in the environment is often mediated by MGEs, which facilitate the HGT of ARGs among microbial populations [44]. The network of correlations between ARGs and MGEs is depicted in Figure 4. In this figure, nodes (circles) represent different subtypes of ARGs or MGEs, while edges (lines) indicate the associations between them. Nodes of different colors signify various subtypes of ARGs or MGEs. Notably, sul1 is associated with the integron In2-18, the transposon Tn6279, and the plasmid pSALNBL1 (r > 0.77, p < 0.05), suggesting that the sul1 gene may propagate within bacterial populations through the In2-18 integron. The gene sul2 is linked with transposons Tn21 and Tn201 (r > 0.78, p < 0.05), and ermG is associated with pKPC_CAV1411, Tn6233, and In607 (r > 0.77, p < 0.05), indicating that ARGs can be disseminated via multiple MGEs. Furthermore, aadA and bacA are both related to the plasmid pSALNBL118 (r > 0.83, p < 0.05), implying that multiple ARGs may coexist within the same host microorganism or on the same MGE, and that HGT may facilitate the spread of ARGs. Integrons such as In2-18 and In607 represent a significant class of MGEs capable of integrating and carrying multiple ARGs, forming so-called “gene cassettes”. These gene cassettes can be transferred between bacteria through transposition, significantly enhancing the diffusion of ARGs [45]. Transposons like Tn6085 and Tn2010 provide another mechanism by which ARGs can be excised and integrated into different genomes, facilitating their movement from one genome to another [46]. Plasmids such as pSALNBL1, pKPC_CAV1411, and pSALNBL118 are circular DNA molecules in bacteria that can replicate autonomously and be transferred between bacteria via conjugation. Plasmids often carry multiple resistance genes, making them crucial vectors for the HGT of ARGs [47].

Research demonstrates that the biofilm environment on MP surfaces enhances the exchange of MGEs such as plasmids and transposons, which frequently carry ARGs [48]. The dense proximity of bacteria within these biofilms significantly increases the opportunities for the exchange of such elements. Within this microenvironment, ARGs can be disseminated among diverse bacterial populations through mechanisms including the insertion of transposons and the conjugative transfer of plasmids. This facilitation of gene transfer underscores the role of MPs as a vector in the propagation of ARGs within microbial communities.

3.3. The Effects of MPs on Microbial Communities

Research indicates that the presence of MPs may alter the existing microbial community structure, promoting the proliferation of bacteria that are capable of surviving on plastic surfaces and potentially carrying ARGs [49]. To investigate the dynamic response of microbial communities to PE, PET, and PLA-MPs during the AD process, analyses of bacterial and archaeal communities were conducted (Figure 5). The data reveal that the dominant bacterial phyla include Proteobacteria (52.16~59.23%), Actinobacteria (24.06~35.32%), Firmicutes (8.61~11.40%), Bacteroidetes (1.54~3.03%), and Chloroflexi (1.29~1.69%). During the AD process, many species within Proteobacteria decompose complex organic substances by initially breaking down large organic molecules such as proteins, fats, and carbohydrates into smaller molecules like sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids [50]. Actinobacteria primarily participate in the preliminary decomposition of certain types of complex organic matter in anaerobic digestion systems, with some capable of degrading recalcitrant substances such as cellulose and lignin under anaerobic conditions [51]. Throughout the AD process, Firmicutes are among the primary producers of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These VFAs are crucial precursors for methane production, playing a vital role in the methanogenic activity of archaea [52].

At the genus level, dominant bacterial genera include Bradyrhizobium (4.32~4.83%), Streptomyces (3.02~4.11%), Pseudomonas (2.35~2.68%), Acidovorax (1.87~3.12%), and Mycobacterium (1.30~2.23%). Bradyrhizobium, typically linked to nitrogen fixation in plant roots, also plays a role in transforming organic nitrogen in anaerobic environments, thereby potentially enhancing the system’s nitrogen cycling efficiency [53]. Streptomyces, a genus of soil bacteria known for decomposing complex organic materials like cellulose and lignin, may facilitate primary decomposition within anaerobic digestion systems, enabling other microorganisms to further utilize the breakdown products [54]. Pseudomonas is a genus with a robust metabolic capacity, capable of degrading a wide array of organic pollutants, including some recalcitrant compounds and MPs [55]. For instance, Pseudomonas sp. can degrade polyethylene and polypropylene, commonly used in manufacturing plastic bags and containers. Exposure to low concentrations of MPs has been shown to significantly increase the relative abundance of Pseudomonas (0.025%~0.17%), whereas high concentrations of MPs inhibit it (−0.14%~−0.10%) (one-way ANOVA, F = 5.72, p < 0.05). Low concentrations of MPs may trigger stress responses in Pseudomonas, thereby enhancing its metabolic activity and adaptability. Conversely, high concentrations can release chemicals, such as additives or plasticizers, that prove intolerable or toxic to the bacteria, thereby inhibiting their growth [56]. Acidovorax, commonly found in aquatic environments and soil, is believed to play a significant role in biodegradation and pollutant treatment. Within anaerobic digestion processes, these bacteria may enhance the stability and efficiency of the system [57].

To analyze the potential microbial hosts of ARGs and to explore the intrinsic connections between ARGs and bacterial communities, a network analysis of ARGs and bacterial communities was conducted. As depicted in Figure 6, a significant positive correlation exists between 20 bacterial genera and 23 ARGs. This network analysis depicts interactions between various bacterial species and ARGs. In this figure, each node represents either a species or an ARG. The color of each node denotes the genus to which the species or ARG belongs, while the size reflects their relative abundance. These microbial groups are predominantly concentrated in genera such as Bradyrhizobium, Streptomyces, Pseudomonas, Acidovorax, Mycobacterium, Microbacterium, Mycolicibacterium, Paracoccus, Rhodobacter, Rhodococcus, Propionibacterium, Hyphomicrobium, Alicycliphilus, Burkholderia, Hungateiclostridium, Rhodopseudomonas, Rhizobium, Corynebacterium, and Micropruina, all of which are core bacteria ubiquitously present in AD reactors. The potential hosts for the bacA gene include Pseudomonas, Microbacterium, Propionibacterium, and Alicycliphilus. The ermG gene has the most potential hosts, showing significant positive correlations with all aforementioned bacterial genera except for Pseudomonas, Acidovorax, Mycobacterium, Burkholderia, and Rhizobium (r > 0.75, p < 0.05). Microorganisms known to degrade MPs primarily consist of specific fungi and bacteria, including Pseudomonas and Rhodococcus. Notably, Rhodococcus, a bacterium recognized for its robust biodegradation capabilities, is capable of decomposing a variety of organic pollutants. This bacterium targets the polymer chains of certain plastics, thereby facilitating their degradation [58]. In the AD system, Propionibacterium and Alicycliphilus are identified as multidrug-resistant microbes, harboring multiple ARGs. Notably, Propionibacterium exhibits significant positive correlations with six ARGs, bacA, qacEΔ1, ermG, aadA, and ermT, while Alicycliphilus shows significant positive correlations with five ARGs: bacA, ermG, aadA, ermT, and ermF (r > 0.72, p < 0.05). Propionibacterium, an anaerobic or facultatively anaerobic bacterium, is ubiquitously found in various human biomes, including the skin, oral cavities, and intestines [59]. A prolonged and frequent use of antibiotics can lead to the emergence of ARGs within these bacterial communities, including resistance to macrolides, tetracyclines, and beta-lactams. Therefore, during the AD process, exposure to MPs may elevate the risk of transmission of pathogenic bacteria containing ARGs.

3.4. Changes in Functional Genes Revealed by Metagenomic Analysis

Based on the aforementioned results, within the AD system, ARGs are disseminated among bacteria via HGT under conditions of MP exposure. Typically, bacterial cells may express or silence specific functionalities contingent upon the survival necessities dictated by varying environmental conditions. The propagation mechanism of ARGs represents a stress response of bacterial cells to antibiotics. For instance, Hu et al. identified potential mechanisms by which MPs facilitate the horizontal mobility of ARGs, including the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), alterations in cell membrane permeability, exopolysaccharide (EPS) secretion, and ATP synthesis [60]. Consequently, this study employed metagenomic sequencing to analyze gene functions in samples with different MP amendments and control groups, investigating the functional genes and metabolic pathways correlated with the HGT of ARGs (Figure 7). This approach underscores the intricate interplay between microbial response and environmental stressors, thereby providing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underpinning ARG dissemination in response to MPs exposure.

ROS, byproducts of cellular metabolism, can be induced by environmental stressors such as exposure to MPs and are capable of damaging DNA, proteins, and lipids, thereby triggering a cellular stress response [61]. For instance, MPs may harbor heavy metals or other oxidative compounds on their surfaces, exacerbating oxidative stress in bacteria. Furthermore, the intrinsic physical structure of MPs may impart mechanical stimuli to bacterial cells, further catalyzing the production of ROS. The SOS response not only facilitates the repair of DNA damage but may also activates MGEs that harbor ARGs [62]. As depicted, exposure to three distinct types of MPs has been shown to enhance the relative abundance of genes related to ROS production. Notably, exposure to 200 mg/L of PE-MPs resulted in the greatest increase in the relative abundance of these genes, a rise of 5.8%. This finding aligns with those of Wei et al., who reported similar effects under comparable conditions [63].

MPs may indirectly facilitate the HGT of ARGs by affecting the permeability of cellular membranes. The permeability of these membranes is a critical determinant in the exchange of cellular materials, including the transfer of MGEs such as plasmids and transposons, which frequently carry ARGs. Initially, the rough surfaces or sharp edges of MPs may physically damage bacterial cell membranes, leading to ruptures or the formation of pores. Additionally, MP surfaces may adsorb harmful chemical substances, including heavy metals and organic pollutants, which can directly compromise the integrity of the cell membrane or alter the fluidity and functionality of membrane lipids [64]. MPs can increase the production of ROS, which themselves can oxidize membrane lipids, leading to lipid peroxidation reactions that disrupt the structure of the cell membrane and increase its permeability. This enhanced membrane permeability may promote the exchange of plasmids and other MGEs carrying ARGs [48]. According to metagenomic data, exposure to PE, PET, and PLA-MPs increased the relative abundance of genes related to membrane permeability in anaerobic digestion systems. Specifically, under exposure of 200 mg/L PE-MPs and 200 mg/L PET-MPs, genes related to membrane permeability increased by 3.53% and 2.66%, respectively, while PLA-MPs showed changes in the relative abundance of genes. The Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) is a ubiquitous secretion system in bacteria that facilitates the transfer of DNA and proteins between bacteria and even between bacteria and host cells. This system plays a pivotal role in the horizontal transfer of ARGs. MPs provide a physical platform that enables bacteria to aggregate and form biofilms on their surfaces. This aggregation increases the frequency of contact between bacteria, potentially enhancing the incidence of T4SS-mediated gene transfer events. The dense colonies formed by bacteria on MP surfaces are particularly conducive to genetic exchanges through systems like T4SS [65,66]. As illustrated in Figure 7, the functional genes related to T4SS are composed of 12 proteins (VirB1–11 and VirD4), which facilitate the transport of macromolecules across bacterial cell membranes [67]. Among all T4SS-related functional genes, VirB3 showed an increase of 182.37% and 97.49% under exposure of 200 mg/L PE-MPs and 200 mg/L PET-MPs, respectively. VirB3 is a key component of T4SS, involved in constructing and maintaining the structure of this complex protein transport system. Factors affecting the relative abundance of VirB3 due to MPs exposure could indirectly influence the efficiency of T4SS and the transmission capability of ARGs.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) serves as an indispensable energy source for bacterial growth and the maintenance of biofilms. Biofilms on MPs provide a protective environment that enhances the exchange of ARGs among bacteria. Interference from MPs with bacterial energy metabolism, due to altered nutrient availability or toxic substances, may impact ATP production, potentially affecting biofilm stability and gene transfer efficiency [7]. Furthermore, MPs may carry or adsorb a variety of organic and inorganic pollutants, which could act either as substrates or inhibitors in bacterial metabolism. Such interactions could influence the efficiency of ATP synthesis, thereby affecting the overall health of the bacteria and their capacity for gene transfer. As illustrated, exposure to 200 mg/L of PE-MPs and 200 mg/L of PET-MPs resulted in an increase in the relative abundance of genes related to ATP synthesis by 31.72% and 25.48%, respectively. Although ATP synthesis itself is not directly related to the HGT of ARGs, the energetic metabolic state of bacteria can influence their response to environmental stresses, including the stress imposed by MPs and gene transfer activities. This underscores the complex interplay between microbial metabolic processes and environmental factors facilitated by MPs pollution.

EPS are a class of multifunctional high-molecular-weight compounds secreted by bacteria, including polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which play a pivotal role in bacterial biofilm formation and significantly influence adaptability to environmental conditions, ARGs, and HGT [68]. The formation of biofilms is contingent upon the secretion of EPS, which not only provides a structural framework but also aids bacteria in resisting external environmental stresses, including those imposed by MPs. The surface characteristics of MPs, such as roughness and chemical composition, may affect the production and composition of EPS, thereby impacting the integrity and functionality of biofilms. An EPS-rich biofilm environment facilitates close contact between bacteria, creating an ideal setting for HGT through mechanisms such as conjugation, transduction, and transformation. In such microenvironments, ARGs can be more readily propagated within bacterial communities. As illustrated, exposure to 200 mg/L of PE-MPs and 200 mg/L of PET-MPs resulted in a maximal increase in genes related to EPS secretion by 5.16% and 5.32%, respectively. MPs, by altering the secretion and functionality of EPS, indirectly promote or inhibit the transmission of ARGs among bacterial populations. This highlights the intricate interplay between environmental alterations induced by MPs and the genetic dynamics of microbial communities.

Source link

Zhonghong Li www.mdpi.com