1. Introduction

Air pollution is a pervasive environmental issue that affects millions of people worldwide, contributing to a range of health problems [

1]. The increased amount of greenhouse emissions has caused a significant deterioration of air quality, which is recognized as a growing concern, specifically due to its far-reaching implications for human health [

2]. Due to industrialization and rapid urbanization, populations have faced multiple health consequences, such as respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological diseases related to the increased prevalence of atmospheric pollutants [

3]. These pollutants include, but are not limited to, particulate matter (PM), nitrogen dioxide (NO

2), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O₃), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [

4]. However, extensive epidemiological research concerning these health consequences and their biomolecular basis has remained insufficiently understood [

5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for studies that examine the molecular and cellular mechanisms that lead to the negative effects of air pollution on health [

6]. In this regard, one of the promising strategies for understanding these mechanisms is the chemical–protein networks, which act as an integrated model of protein–protein interactions (PPIs) and reveal how pollutants can change the biological processes at the molecular level [

7].

Integrating chemical–protein and protein–protein interaction networks into air pollution-related studies will enable the harmonic exploration of complex biochemical paths disrupted by pollutants. Interactions of human chemicals and proteins are known as chemical–protein interaction networks [

8]. These networks give information on how pollutants can attach to proteins, altering their behavior, status, and metabolism and initiating pathological conditions. Particulate matter and heavy metals can induce oxidative stress by interacting with proteins within the antioxidant response network in the body. Mapping these interactions can help researchers anticipate health risks that could arise from different pollutants and outline key proteins that could be used as the basis for new biomarkers to quickly diagnose diseases caused by pollution [

7].

However, protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks elucidate the effects of these chemically modified proteins on larger-scale biological processes. Proteins interact with each other to create a PPI network, and any disturbance in the network leads to cascading effects and various systemic physiological imbalances [

9]. The STITCH and STRING databases predict which proteins are most susceptible to modification by air pollutants and how these modifications contribute to disease progression, particularly in the hematology, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems. Identifying specific proteins and pathways affected by air pollutants is essential for mitigating or reversing their detrimental health impacts. Cytoscape is a tool that identifies critical proteins based on degree centrality, and OmicsBox is a bioinformatics tool that analyzes the functions and pathways of proteins [

10]. Various airborne pollutants have been reported to interfere with proteins that regulate important cellular processes, including inflammation, immune response, and cellular metabolism [

11]. These disturbances may result in chronic diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cardiovascular disorders. Investigating PPI networks allows researchers to follow the chain reaction by which changes in protein function due to air pollution propagate through cellular pathways, complementing the traditional state of the art on air pollution-related disease to gain a more holistic view of molecular information on diseases caused by air pollution [

12].

Recent progress in bioinformatics and computational biology has now made it possible to analyze these huge datasets generated from chemical–protein interactions and PPI networks, thus making better predictions of the impact of air pollution on human health more feasible [

13]. Predictive modeling techniques involved in machine learning algorithms and systems biology approaches enable researchers to combine data from various sources, such as clinical studies, environmental exposure assessments, and experiments in molecular biology [

14]. Identifying the susceptible nodes and pathways in interaction networks can help predict possible health outcomes due to air pollution [

15]. Additionally, they enable the identification of new therapeutic targets to lessen the adverse effects of air pollution and provide the pathway for public health interventions [

16].

These various levels of molecular interactions between pollutants and biological systems serve as the basis for targeted strategies for mitigating the health effects of air pollution. The utilization of chemical–protein and protein–protein interaction networks enhance our understanding of not only the harmful effects of pollutants but also the development of much better prevention and treatment strategies [

17]. With continued growth in the burden of air pollution, applying these advanced tools will be paramount to the protection of human health and the development of policies that will reduce exposure to air pollutants in the years to come. In such a way, researchers are in a better position to predict the possible outcomes of air pollution on human health and scientifically support one of the major environmental challenges facing humanity at present. Our study aimed to investigate the protein–protein interactions (PPIs) of different air pollutants within the human body and identify the impacts of air pollution on human health. This study developed computer models of chemical–protein interactions to facilitate the determination of biomarkers for the early detection of pollution-related disorders.

4. Discussion

Carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) are important gaseous molecules with significant positive and negative biological effects. Even though they are known to be poisonous in greater quantities (over 4 mg/m

3 or 3.5 ppm), they are also essential for preserving cellular homeostasis and controlling several physiological functions [

45]. With an emphasis on their interactions with important proteins, oxidative stress management, and consequences for vascular and metabolic health, this discussion will examine how CO and H₂S affect enzyme activity, cellular pathways, and metabolic activities.

The major effects of CO on biological systems are through the interaction with enzymes, proteins, and cellular pathways responsible for a variety of key physiological functions. Among the well-defined targets of CO are protein arginine methyltransferases, which catalyze protein methylation and control many cellular processes, from gene expression to cell signaling and cell cycle control.

Other important effects of CO involve interactions with proteins implicated in the regulation of oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species. CO modulates the activity of enzymes that are central in the oxidative balance, including HO-1 and HO-2, which are crucial for heme catabolism and the production of biliverdin and carbon monoxide itself. Of these, HO-1 possesses antioxidant properties and is induced by conditions of oxidative stress. CO, through the modulation of HO-1, may have protective effects against oxidative injury [

46]. On the other hand, chronic CO exposure could interfere with cellular homeostasis and promote oxidative injury in conditions such as neurodegenerative disorders, mainly by breaking down the integrity of the blood–brain barrier [

47]. Such breakdown in the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) may lead to enhanced neuroinflammatory responses and is considered an additional factor contributing to cognitive decline.

Further, CO is a player in the processes of vascular homeostasis. It modifies the functions of important oxygen-transport proteins, including cytoglobin and hemoglobin, implicated in oxygen transport and the maintenance of tissue oxygen levels. With the ability to modulate these proteins, CO modifies the delivery of oxygen to the tissues and the cellular responses to hypoxia; as a consequence, the blood flow is changed, as are tissue repair and immune responses [

48]. Moreover, CO acts as an essential modulator of immune responses by tuning the production of inflammatory mediators with protective or pathogenic functions, depending on the context and length of exposure. While in an acute setting, CO can reduce inflammation, on the other hand, chronic exposure may increase inflammatory pathways that may lead to the development of chronic diseases like cardiovascular disorders and neurodegenerative conditions.

This study discovered that carbon monoxide interacts with multiple human proteins, genes, and enzymes that regulate vital functions of human health within tolerable concentrations, including methionine synthesis (ADI1), heme metabolism (BLVRB), and cellular protection (CYGB). Carbon monoxide is produced during heme metabolism by BLVRB enzymes, and extensive amounts of this airborne chemical alter cellular respiration [

26]. Acireductone dioxygenase 1 (ADI1) is responsible for the methionine salvage pathway crucial for methionine synthesis and cellular stress responses [

25]. Low CO levels (10–100 nM) influence methionine metabolism, but high CO levels (>100 µM) can alter enzyme metal centers, such as the iron (Fe

2⁺) in ADI1, reducing catalytic activity [

25]. Another primary interacted protein, cytoglobin (CYGB) protein, is responsible for cellular protection via antioxidant defense, lowering blood pressure, maintaining vascular health via nitric oxide regulation, and promoting cardiac cell survival [

49]. Hemoglobin subunit epsilon 1 (HBE1) plays a crucial role in treating different hematologic disorders and blood cancer, but extensive CO negatively affects the functions of HBE1. Hemoglobin subunit gamma 1 (HBG1) plays a crucial role in fetal oxygen transport, but an extensive concentration of CO (>10 ppm) increases hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen and causes impaired oxygen delivery to tissues. The enzyme betaine homocysteine S-methyltransferase (BHMT) interacts with H

2S and is involved in the conversion of homocysteine into methionine via betaine methyl donor [

36].

Like CO, hydrogen sulfide has also been recognized as an important gaseous molecule in biological systems with significant roles, primarily in regulating metabolic and redox processes. The role of H₂S is being reported to influence a lot of enzymes in sulfur metabolism, most especially in the trans-sulfuration pathway, which has an important role in the detoxification of homocysteine and in synthesizing major sulfur-containing biomolecules. Two important enzymes from the trans-sulfuration pathway are BHMT and CBS. Both of these enzymes are essential to converting homocysteine to cysteine and further synthesizing glutathione, an important antioxidant [

50]. H

2S, through its action on these enzymes, maintains the redox balance and thus supports the maintenance of cellular metabolism, reducing oxidative damage due to ROS. H

2S has a beneficial impact on homocysteine metabolism through the induction of trans-sulfuration enzymes [

37]. The enzyme cystathionine gamma-lyase (CTH) plays an essential role in homocysteine metabolism. A lower concentration (<10 µM) of H

2S increases CTH function by inducing the feedback inhibition mechanism, but a higher concentration (>10 µM) of H

2S decreases transcription and reduces the activity of the CTH enzyme (200 µM) [

40]. MPST-3 plays a key role in the sulfur-containing compounds, and Nagahara [

42] said the elevated levels (200 µM) of H

2S induce oxidation of the MPST-3 enzyme and minimize its activity.

The possibility that H₂S can regulate oxidative stress is intriguing. Since it is a reducing molecule, H₂S can lessen oxidative damage by either directly increasing the cell’s antioxidant defense systems or by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS). For example, H₂S increases the expression and activity of glutathione peroxidase and other antioxidant enzymes, thus protecting the cell from oxidative damage [

51]. This antioxidative role is highly valued in the context of diseases associated with inflammation and oxidative damage, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Furthermore, H

2S plays a role in energy production and metabolic efficiency. By influencing the activity of several enzymes like MAT and methionine synthase, which are responsible for synthesizing important metabolic intermediates, H

2S provides a means to maintain energy homeostasis in the cell. Thus, a further suggestion was made about its ability to ensure an optimum metabolic outcome and to improve mitochondrial process efficiency [

52]. These would have implications for CBS and cystathionine that further support the synthesis of sulfur and methionine, which are important in cellular growth, repair, and energy production. The beneficial roles played by H₂S in the regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation point toward its therapeutic potential in various conditions, particularly where such processes are dysregulated.

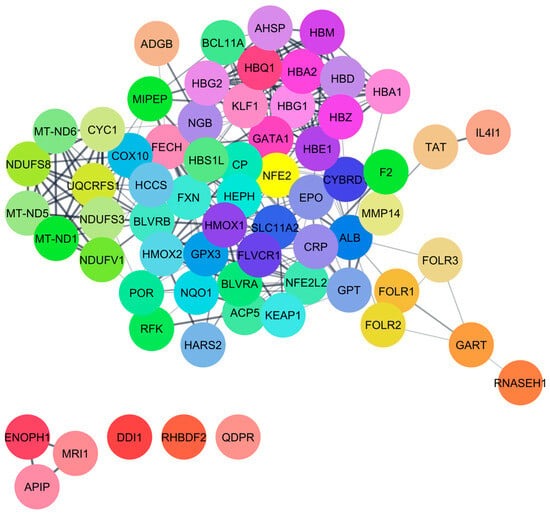

FECH, ALB, and HMOX1 are essential proteins for human health that play a significant role in regulating porphyrin and heme metabolism. These proteins have been identified as critical nodes based on their degree of centrality. Finding the most important nodes in a network based on the degree of centrality allows one to examine its topology, including its resilience and susceptibility to attacks [

53]. Centrality measures employ graph theory and network analysis to evaluate an individual’s position within a protein network. Degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality are used to assess social influence inside networks [

54]. Molecular docking interactions indicated the lowest binding energy, suggesting that CO and H

2S have a weak interaction with these 14 proteins. Multiple investigations have explored the strong binding of CO with the heme pocket of myoglobin; however, we were unable to locate myoglobin within the STITCH database [

55]. CO mostly binds with glycine and aspartate amino acids, and these are responsible for erythropoiesis and oxidative responses. Alternatively, a limited investigation was performed on the interactions of H

2S with proteins; Nery et al. [

56] reported comparable results regarding H

2S interactions with hypoxia-inducible factors.

Both CO and H₂S are therapeutically very important. CO’s role in modulating vascular health, immune responses, and oxidative stress could represent targeted therapies for conditions like hypertension, vascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders. CO-releasing molecules, CORMs, have been pursued as active pharmaceuticals for the delivery of controlled amounts of CO for therapeutic applications, especially in diseases that feature excessive oxidative stress and inflammation.

However, although both gases possess therapeutic potential, dosing and delivery mechanisms are still big challenges. At high concentrations, both CO and H₂S are toxic; thus, it is very hard to translate their beneficial effects into clinical practice. For this reason, ongoing research is needed to develop ways to safely and effectively exploit these molecules in therapeutic settings. However, the therapeutic potential of these gases must be carefully harnessed to avoid their toxic effects, underscoring the importance of continued research in this area.

5. Conclusions

The increases in greenhouse gas emissions due to urbanization and industrial activities have been linked to a significant fall in air quality, now regarded as a foremost risk to public health globally. The emission of pollutants including particulate matter (PM), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) has worsened air quality and is implicated in diverse health effects, predominantly on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. These pollutants induce climate change and release a series of cellular and molecular effects in the human body, which lead to chronic diseases like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and heart disease. The priority in environmental health research has been to better understand these health effects at the molecular level. In particular, studies concentrating on the interactions of these pollutants with proteins at the molecular level will illuminate how these compounds throw biological functions out of gear and lead to the development of such diseases.

Air pollutants harm and benefit human health by interacting with cellular proteins. These cellular proteins are critical in maintaining normal physiological functions. Once inhaled, air pollutants bind to proteins, modifying their conformation, activity, or expression. In turn, this process disrupts essential biological functions such as immune responses, oxidative stress regulation, and cell signaling. Oxidative stress, a prominent mechanism through which air pollutants cause damage, is mediated largely by proteins involved in antioxidant defense mechanisms. Chemistry–protein interaction analysis is a very innovative tool to unveil the biological effects of air pollution. Scientists can get insight into the molecular pathways that are implicated after exposure by identifying the specific proteins that interact with different pollutants. In recent years, advances in bioinformatics and computational biology have allowed researchers to analyze the vast data associated with these chemical–protein interactions.

The research discusses the interaction between carbon monoxide (CO) and various proteins subsequently modifying several biological functions like methionine biosynthesis, heme metabolism, and cell protection; for instance, CO interacts with acireductone dioxygenase 1 (ADI1) and biliverdin reductase B (BLVRB), which has various negative effects on several cellular and metabolic functions. CO at low concentrations (about 10–15 ppm) seems to enhance erythropoiesis and affects methionine metabolism, while higher concentrations (>50 ppm) interfere with the proper functioning of hemoglobin, meaning cellular respiration is affected, and oxidative stresses occur. Such interactions may bring serious implications for health, such as respiratory and cognitive defects. In addition, the involved proteins may link with different biological pathways such as heme biosynthesis, platelet degranulation, and oxidative stress defense, thus emphasizing that CO exposure can have a very far-reaching effect.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) also inhibits key enzymes involved in the metabolism of homocysteine and sulfur-containing compounds and methylation processes. H2S inhibits essential enzymes such as betaine homocysteine S-methyltransferase (BHMT) and cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS), which disrupts proper metabolism. A low dose of H2S stimulates homocysteine metabolism and the methionine cycle, while a higher concentration gradually oxidizes enzymes, inhibits transcription, and damages further cellular function and metabolism. The critical pathways’ interaction with H2S mainly takes part in sulfur metabolism, methylation, and the regulation of homocysteine.

Also identified were critical proteins with high centralities in the network of protein interactions for both CO and H2S. For CO, involved in heme metabolism, cellular immunity, and stress response are proteins such as FECH, HMOX1, and ALB, while for H2S, CTH, CBS, and CBSL are involved in sulfur metabolism, amino acid regulation, and redox balance. The study further elaborates on these proteins’ regulatory roles in diverse biochemical processes, such as porphyrin metabolism and sulfur amino acid metabolism, as well as the regulation of gene expression, all of which emphasize how CO and H2S exert profound effects on human well-being.

In conclusion, molecular interactions between pollutants and proteins, in terms of their biological effects, are undoubtedly of great importance for understanding the health consequences of air pollution. Large strides forward in bioinformatics and computational biology, including the STITCH 4.0 and STRING 9.0 tools, have made it possible to elucidate the chemical–protein interaction networks and protein–protein interaction pathways and elaborate the molecular mechanisms of air-pollution-related diseases. Further digging into these networks and the disruption caused to biological processes may help to determine health outcomes, suggest new therapeutic approaches, and possibly prevent or ameliorate air pollution’s harmful effects. This type of research is certainly of the utmost importance in matters of public health and will form a stronger basis for understanding how the environment can influence human disease.