The United States is facing a pivotal moment in its fight against climate change as President Donald Trump carries out plans to roll back those efforts.

In 2019, when New York passed its landmark Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, or CLCPA, it became a shining example of national climate action. The law established a roadmap for the state to mostly phase out planet-warming fossil fuels like gas by 2050, and transition to clean energy instead.

But 96 percent of the downstate region is still powered by fossil fuels, through pipelines for natural gas. In total, only about 29 percent of the Empire State’s electricity comes from renewable sources.

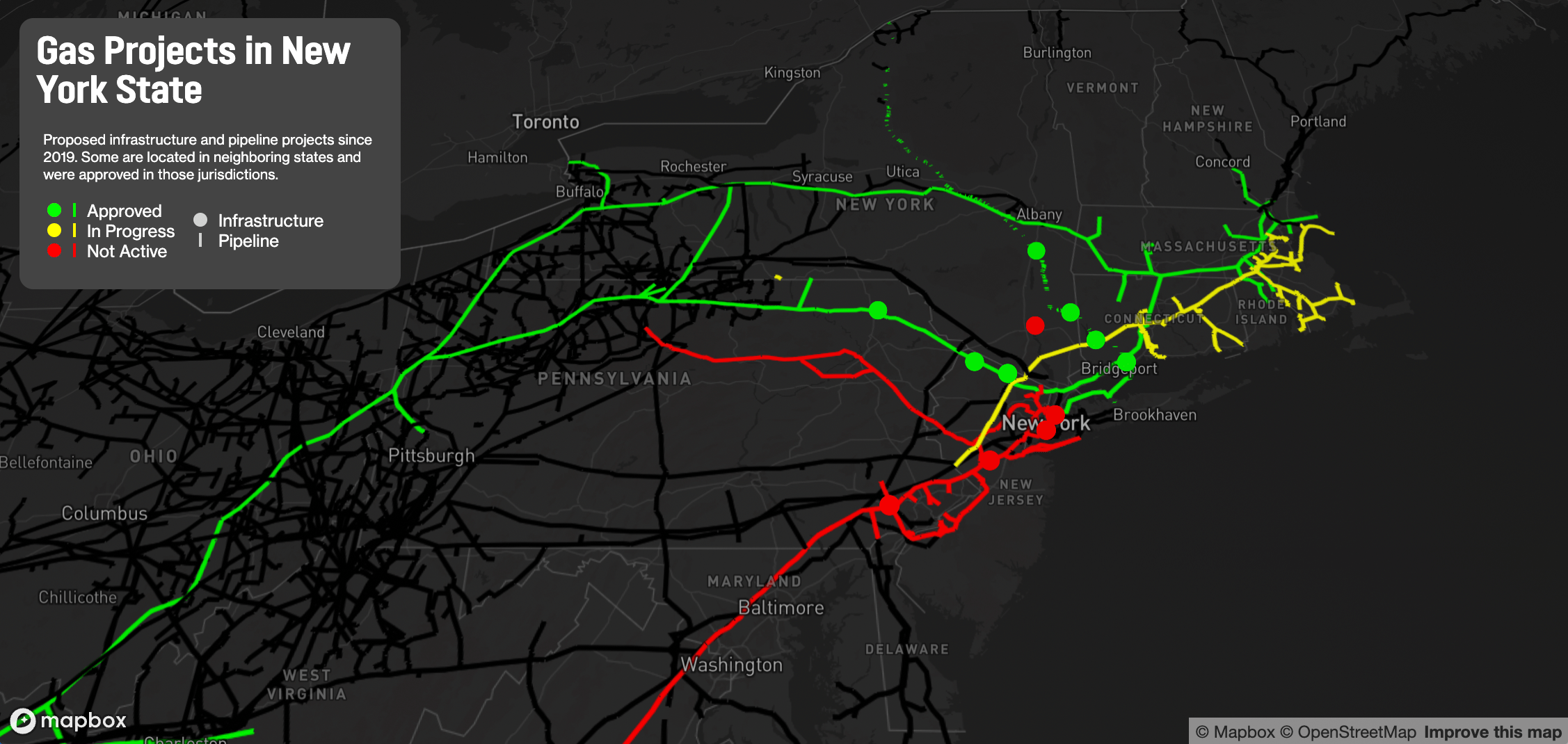

Since the CLCPA was passed, gas suppliers have made 10 attempts to increase the flow of gas across the state. But none secured New York permits to move forward, until now.

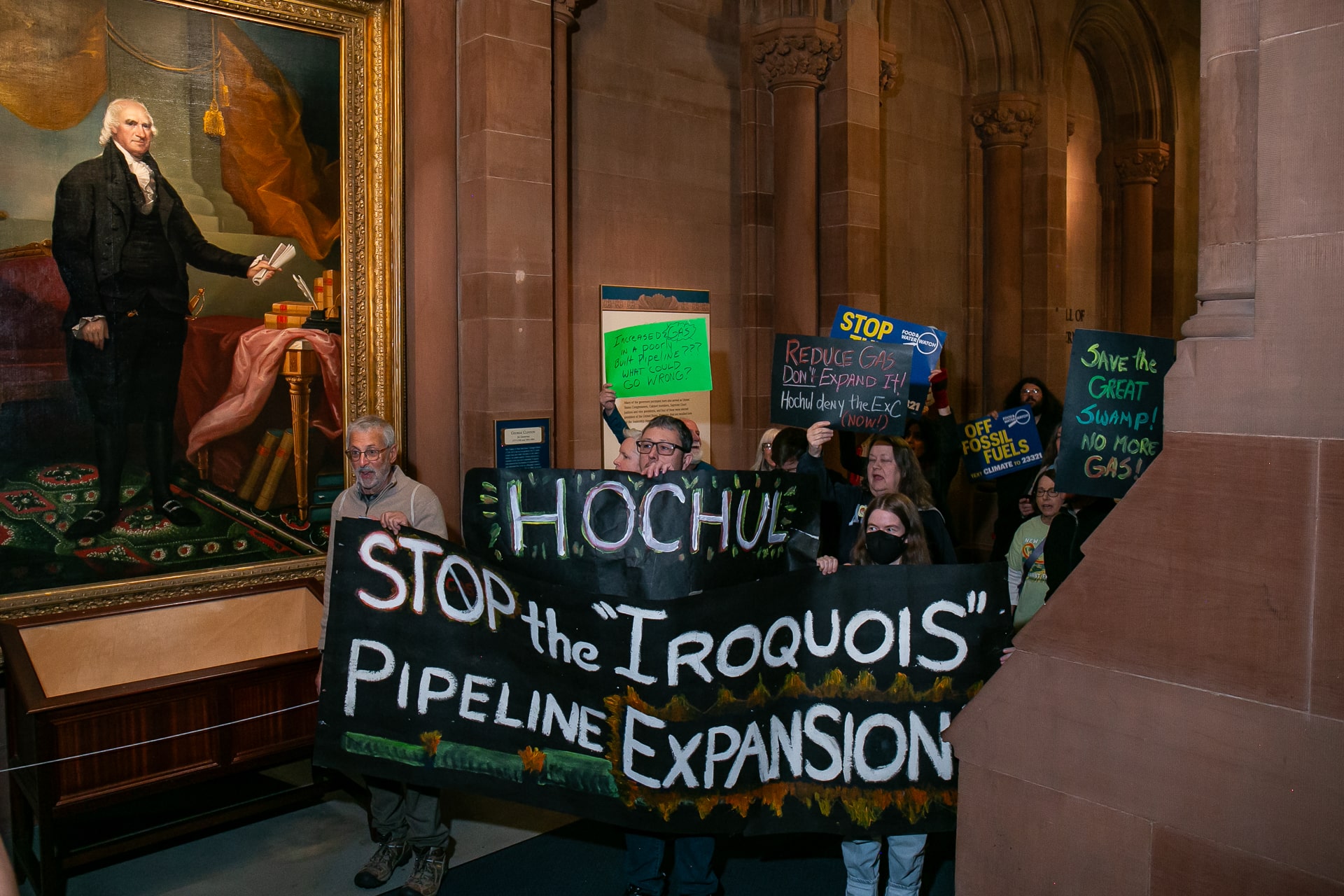

On February 7, the state greenlit an enhancement project by Iroquois Pipeline Company, which will boost the capacity of four facilities that compress gas to push more of it into the city.

Adi Talwar/City Limits

The approval of Iroquois’ project, which utility companies argue is needed to heat New Yorkers’ homes in the coldest months, amps up planet-warming pollution—and signals that the state’s commitment to reaching its climate goals is faltering, critics say.

The Iroquois project alone could generate $3.78 billion in climate damages through 2050 and add the equivalent of 186,000 passenger cars to the road in planet-warming gasses. It will also spew pollution into communities like Athens, a town in southeast central New York that filmmaker Lisa Thomas calls home.

‘Right under your nose’

When Lisa Thomas first moved out of New York City’s bustling concrete jungle 23 years ago for the quiet town of Athens, she was looking for a peaceful place to settle down. She believed her new 16-acre property, surrounded by trees, was it.

“I wanted to have a place that I could call home and feel safe in. But somehow now it feels like that’s in jeopardy,” Thomas said.

Nearly two years ago, Thomas learned that the multinational gas supplier, the Iroquois Pipeline Company, had plans to more than double the capacity of a compressor station a few miles down the road from her home.

Compressor stations, which make gas smaller so more of it can get pushed through the system, are widely regarded as health hazards. They spew air pollutants that can contribute to preterm births, asthma, heart disease, strokes, and a shorter lifespan, environmentalists say. And emissions released by compressor stations in New York contained 39 cancer inducing chemicals, one study found.

“A lot of times the most dangerous things are actually happening right under your nose, and you don’t even know it,” Thomas said.

Athens isn’t the only town where Iroquois was granted air permits from New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to enhance its infrastructure. Another compressor station in Dover, a town in the southeastern tip of the state, will get a boost too. And the company hopes to do the same in two facilities in Connecticut, although permits for those are yet to be issued.

The venture, known as the ExC Project, aims to push an extra 125 million cubic feet per day of gas into New York City. To make it happen, 48,000 horsepower of new compression will be added to the four compressor stations along Iroquois’ pipeline, which starts in Canada and stretches all the way to the Big Apple.

Patrick Spauster

Until ExC got New York’s seal of approval, the Empire State had denied all post-CLCPA requests from fossil fuel suppliers to secure permits for expansion.

The move signals that the state’s commitment to phasing out fossil fuels is waning, environmentalists say. Deadlines laid out by the climate act, to have 70 percent of the state’s energy come from renewable sources by 2030, have already been pushed back by three years.

Utility companies National Grid and Con Edison argue their New York City customers need the added supply, especially in the colder months. “Issuing the permits for the Iroquois ExC project is essential for maintaining a safe, adequate, and reliable gas supply for downstate New York customers,” DEC agreed in an email.

But the approval tightens the grip of dependency on fossil fuels in a state where gas-fired power plants generated twice as much electricity as any other fuel source in 2023. It will also increase pollution in towns like Athens, critics say, and add to the national carbon footprint at a time when President Trump is scaling back efforts to fight climate change.

The project has the potential to generate $3.78 billion in climate damages over the next 25 years, according to an analysis put together by the Environmental Protection Agency when Iroquois sought federal permits for the venture.

“[New York’s administration] is leaning into the wave of conservative policy. It just feels really tone deaf to what most New Yorkers actually care about and want,” said Emily Skydel, New York Hudson Valley senior organizer at Food & Water Watch.

‘A political problem’

When New York first passed the Climate Act, the state’s commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions appeared unwavering. Government officials were shutting down bids to bring more gas into the state left and right.

Gas supplier Williams Transco, which sought to build a massive pipeline stretching from Pennsylvania to New York City’s Rockaways, had its third request for a state permit rejected in the spring of 2020. A year later, the state also denied attempts by Danskammer and Astoria Gas Turbine Power to turn peaker plants—used only during times of peak demand for gas—into full service facilities.

Each time, DEC gave the same reason for the rejections: the projects generated too many planet-warming emissions, making them “inconsistent with the requirements of the Climate Act.”

Kevin P. Coughlin/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo

But since then, officials’ tone has changed.

In an interview last summer, Governor Kathy Hochul said that New York will probably “miss” hitting the goals set by the CLCPA “by a couple of years.”

“The goals are still worthy. But we have to think about the collateral damage of all of our major decisions,” Hochul said, citing concerns about the transition to clean energy still being too costly for consumers. “You either mitigate them or you have to rethink them.”

Seven months later, Iroquois’ compressor station expansion was approved even though the amount of climate pollution the project is set to emit exceeds limits the DEC previously considered inconsistent with the climate law.

Astoria Gas Turbine Power’s buildout, for instance, was set to launch 723,872 tons of the potent greenhouse gas carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) into the atmosphere per year. The amount, the DEC said at the time, was “substantial” as it would “interfere” with achieving the statewide emission limits set for 2030.

Meanwhile, Iroquois’ ExC project, which is projected to generate 859,057 tons of CO2e annually, did get DEC’s stamp of approval. The amount is comparable to adding 186,000 passenger cars to the road, the environmental group Sierra Club says.

As a condition for issuing the permits, however, DEC said Iroquois is required to invest $5 million in “mitigation efforts” to “minimize emissions.” That will include investing in electric vehicle charging stations or establishing a program for heat pumps, a clean electric solution to heating homes.

But efforts like these just don’t add up, environmentalists argue.

Adi Talwar/City Limits

“Green lighting projects that have a tiny marginal impact in lowering emissions are not good enough,” said Josh Berman, an attorney at Sierra Club’s Environmental Law Program.

Berman points out that the state is only marginally below 1990 greenhouse gas emissions levels, even though the climate act says it’s supposed to be 40 percent below those levels in just five years.

“We need to be doing things that are fundamentally lower-emitting and much cleaner,” Berman added.

Just 29 percent of the state’s electricity currently comes from renewable energy like solar and wind, a far cry from the goal set by the climate law, which calls for 70 percent by 2030. A state report issued last year admitted that the Empire State would probably only hit this goal by 2033.

“I think that it’s very much down to a failure of leadership by Governor [Kathy Hochul] to take seriously our legal mandate to hit our climate goals,” said Michael Paulson, co-chair of the Public Power Coalition, an environmental group that supports the shift to renewable energy.

“It is a political problem and a problem of leadership,” Paulson added.

The governor did sign legislation last year that would force big oil companies to pay for climate change destruction, and banned fracking for gas with a new technique that uses carbon dioxide. Plus she invested $1 billion “in clean energy projects in this year’s budget,” her office pointed out in an email.

“Governor Hochul has demonstrated a clear commitment to an affordable and reliable transition to a clean energy economy,” Hochul’s Deputy Communications Director Paul DeMichele added.

Inconsistent funding, long timelines for the completion of large scale renewable energy ventures and cancelled contracts have delayed the shift to renewables, the state comptroller’s office said.

In the meantime, the gas industry has quietly sought to expand by building out several existing facilities.

Patrick Spauster

More gas is already being funneled into New York’s Westchester County thanks to compressor station expansions in neighboring states that concluded last year. The plan, carried out by the Tennessee Gas Pipeline company, brought a new compressor station and the enhancement of two others to New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

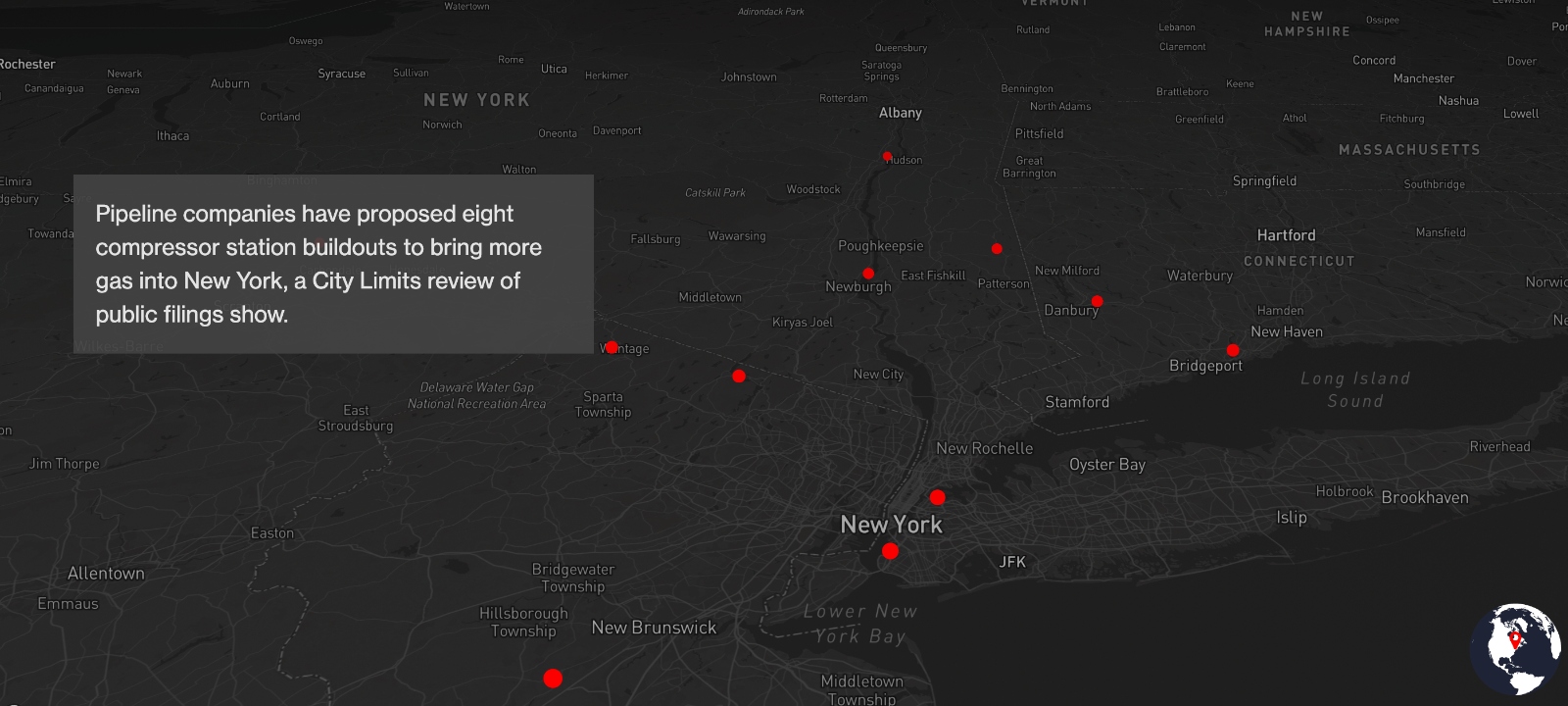

Within the last five years, pipeline companies have proposed eight compressor station buildouts to bring more gas into New York, a City Limits review of public filings show. Of those, three were approved by neighboring states.

“This is a strategy used by the fossil fuel industry to expand their infrastructure in a way that makes it look like they’re not really doing it,” Skydel from Food & Water Watch said.

“What people need to understand is that this is still adding gas into the system. It’s increasing air pollution and it’s still doing serious harm to our climate, to our health.”

A necessary evil?

For the nearly 4,000 people who live in the village of Athens, the approval of the Iroquois pipeline’s ExC project is not welcome news, Mayor Amy Serrago says.

“For Athens there’s really no community benefit. It’s all downsides,” argued Serrago.

Environmentalists say compressor stations, which operate on high pressure to boost more gas through the system, are accident-prone facilities. Weymouth compressor station in Massachusetts is a case in point, as the facility has reportedly had at least three unplanned leaks.

Athens is already deemed a disadvantaged community under the state’s climate criteria because it faces economic, health and environmental challenges; the town is home to large scale industrial activity like the Athens Generating plant.

“We need to find another solution to [New York’s] energy problem. I know it’s not an easy overnight fix, but we can’t keep piling these things onto our rural communities,” Serrago said.

Adi Talwar/City Limits

The Iroquois Pipeline Company told DEC that the project “will not disproportionately burden” Athens or “negatively impact human health.”

“The proposed project would not have a significant adverse impact on the environment or on individuals living in the vicinity of the project facilities, including environmental justice communities,” the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) agreed during proceedings that greenlit the project on the federal level.

But when it comes to the environment, the Iroquois Pipeline Company doesn’t have the best track record. In the spring of 1996, it pleaded guilty to four felonies for violating federal environmental laws. (Ironically, the company carries the name of the group of six Native American nations that were displaced from their territories in the 17th and 18th centuries.)

Still, fears that there won’t be enough renewable energy to heat the homes of New York residents permeate, especially in the New York City region, where dependence on fossil fuels has increased over the last five years.

In 2021, the state shut down the nuclear power plant at Indian Point, long regarded by some as an environmental health hazard. But it also supplied a large chunk of carbon-free electricity downstate.

After it began ceasing operations in the spring of 2020, downstate fossil fuel generation increased from 69 percent in 2019 to 96 percent in 2022, according to New York Independent System Operator (NYISO) reports analyzed by electrical engineer Keith Schue. Schue is part of the New York Energy and Climate Advocates, which champions the use of nuclear energy.

A slight increase in renewable energy reduced downstate dependency on fossil fuels to 94 percent last year, according to NYISO’s most recent report. But that’s still falling short of what’s needed to move off gas.

Darren McGee/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul

For Schue, the state is caught in a conundrum: while it wants to support the shift away from fossil fuels, it doesn’t have enough clean energy to do it. So it’s forced to approve projects like Iroquois to keep electricity flowing.

“People want to demonize Governor Hochul right now about this decision. But I don’t think that’s fair because ultimately we can’t let the lights go out. You can’t let people not have energy in their homes. So she’s stuck between a rock and a hard place,” Shue said.

Utility companies National Grid and Con Edison, which turn a profit by selling Iroquois’ gas to New York City residents, also say more capacity is needed.

The added supply will “significantly increase deliverability into capacity-constrained downstate New York,” National Grid said in a document issued to FERC. The utility “expects its demand growth to remain steady in coming years due to population and economic growth as well as continued oil-to-gas conversions.” Their priority, the company said in an email, is ensuring “customers have access to the energy they need.”

Con Edison agreed, adding that it needs the boost in capacity to “meet our customers’ demand on the coldest expected winter day.” A spokesperson also noted that “the approval of these permits is a step toward enhancing the reliability of our gas supply from interstate pipelines.”

The Department of Public Service (DPS), the agency that oversees utilities in New York, said in an email that it was “firmly committed” to transitioning to “cleaner and renewable energy sources.”

But it also painted the project as a necessary evil. The agency pointed out that New York came close to a “wide scale gas outage” in December of 2022, when Winter Storm Elliott led to a sudden reliance on electric generators, spiking demand for gas.

“This project is strictly about solving a safety and reliability issue on the system as it currently exists. The safety of New Yorkers during extreme cold weather is paramount, and we cannot compromise on the reliability of the state’s utility systems,” DPS said in an emailed statement.

‘Fear mongering’

Members of the environmental community, however, strongly disagree.

“One of the main tactics of the oil and gas industries is to fear monger with regards to public safety and the reliability of electricity,” said Niki Cross, an attorney at the nonprofit New York Lawyers for the Public Interest (NYLPI).

“They point to scenarios like Winter Storm Elliott and say that we were close to having an emergency breakdown of the system. But in fact, we didn’t and those storms are less and less likely to happen because of the warming climate,” they added.

New York City, once considered a humid continental climate, was redefined five years ago as a humid subtropical climate zone by the National Climate Assessment.

Plus, the amount of gas that utility companies National Grid and Con Edison say they need is based on unrealistic demand, environmentalists argue.

Both utilities use “65 Heating Degree Days” to measure how much energy is needed to heat buildings. This measure is equivalent to the temperature at Central Park reaching zero degrees over the course of an entire day. The last time that happened in New York was in 1934, experts say.

The forecasts, known as “design day demand,” are based on “extremely cold temperature conditions that occurred 90 years ago and have occurred only twice in the last 120 years,” Cross said.

A series of upcoming environmental laws are expected to further lessen New York’s need for fossil fuels. A state prohibition on the use of gas equipment in new construction takes effect in 2026 for new buildings of seven stories or less, and in 2029 for larger buildings. New York City’s own version of this law started last year. And starting this year, the city’s Local Law 97 will fine buildings larger than 25,000 square feet that fail to reduce their carbon emissions through energy efficiency upgrades.

Still, the state’s utility regulator, DPS, said that although these recent policies “reduced the overall growth of gas demand in New York City,” the demand for gas has “continued to grow, albeit at a slower pace” in a portion of ConEd and National Grid territory.

But a third party study commissioned by DPS itself begs to differ. After 2027, “no additional supply assets” like adding “additional capacity” to pipelines “will be required” to meet National Grid and ConEd’s “design day demands,” the 2023 report found.

“The question is: can you meet those design day goals with a portion of electrification? If you electrify 10 percent of [utility] customers, then you have 10 percent excess supply that you could use to cover greater demand during a winter peak,” said Michael Bloomberg, managing partner at the energy consulting firm Groundwork Data.

“You could do the same thing just through building efficiency. You don’t necessarily need to do it through added supply,” he argued.

Nationally, Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” agenda promises to increase the use of fossil fuels, as government incentives and federal permits needed for clean energy initiatives have already begun to unravel.

The Trump administration paused new leases and halted new permits for projects that generate clean energy using offshore wind farms. And it threatened to revoke federal approval for New York’s congestion pricing program, a toll that encourages Manhattan commuters to swap their cars for less carbon-emitting public transit.

“In New York we’re going to be facing a lot of headwinds coming from the federal government,” said Daniel Zarrilli, former chief climate policy advisor at the New York City Mayor’s Office.

“State governments need to be as bold as they can at this moment,” he added. “And so I would hope that New York would be at the leading edge on that. But there’s a lot of pressure pushing the other way right now.”

Source link

Mariana Simões, City Limits grist.org