As it will be shown in the next subsections, the semantic nature of the subjects seems to be a key factor in determining the likelihood of their covert realization. Indeed, 367 (92.68%) of the 399 identified NSs are expletives, while only 29 (7.32%) are referential.

6.1. Expletive NSs

The analysis of the sub-corpus showed that 1789 sentences out of 4996 (35.81%) feature an expletive subject, and as mentioned above, the absolute majority of the NSs are expletives. Indeed, null expletives constitute 20.51% of the total expletive subjects, while only 0.9% of the referential subjects are left unexpressed.

Specifically, null expletives have been identified in different syntactic contexts, namely existential (

il)

y a constructions (34a), impersonal (

il)

faut and (

il)

arrive sentences (34b–c), light verb structures featuring (

il)

fait (34d), and fixed expressions such as

s’(

il)

vous plaît (34e)

5 and (

il)

vaut mieux (34f):

| (34) | a. | (Il) | y | a | plein | de | gens |

| | expl | there | have.3sg | plenty | of | people |

| | ‘There are plenty of people’ | (Auréane) |

| b. | (Il) | faut | qu’ | on | y | aille |

| | expl | need. 3sg | that | one | there | go.subj.3sg |

| | ‘We need to go there’ | (Apéritif) |

| c. | (Il) | peut | m’ | arriver | de | m’ | adonner |

| | expl | may.3sg | to.me | happen.inf | of | my.self | devote.inf |

| | à | d’ | autres | produits | | | |

| | to | of | other | products | | | |

| | ‘I may occasionally indulge in other products’ | (Auréane) |

| d. | (Il) | faisait | vraiment | chaud |

| | expl | make.pst.3sg | really | hot |

| | ‘It was really hot’ | (Apéritif) |

| e. | T’ | enlève | ça | s’(il) te plaît |

| | pron.dat.2sg | remove.imp.2sg | that | please |

| | ‘Please take it off’ | (Montage) |

| f. | (Il) | vaut | mieux | avoir | l’ | air | de |

| | expl | be.worth.3sg | better | have. inf | det | air | of |

| | bien | vouloir | engager | la | conversation |

| | well | want. inf | engage. inf | det | conversation |

| | ‘It’s better to look like you want to start the conversation’ | (Apéritif) |

Furthermore, it is important to note that these structures have varying rates of occurrence within the sub-corpus examined, as reported in

Table 2.

Data show that existential (il) y a constructions constitute the great majority, accounting for 79% of the occurrences. Impersonal expressions featuring (il) faut follow with 16.22%, while sentences with (il) fait represent a smaller proportion at 2.7%. Light verb constructions with (il) arrive and fixed expressions such as s’(il) vous plaît and (il) vaut mieux exhibit minimal occurrences in the dataset. These varying rates of occurrence underscore the differential distribution and usage patterns of expletive structures in French colloquial speech, reflecting the diverse linguistic contexts in which they appear.

Turning to the analysis of NSs across these syntactic constructions, results show significant variations in their frequency and distribution, as shown in

Table 3.

As can be seen in

Table 3, speakers tend to realize most Null Subjects in existential (

il)

y a constructions (82.89%). Conversely, impersonal (

il)

faut sentences show a more balanced distribution, with no significant difference between null and overt realizations (

z = −0.68,

p = 0.496). Interestingly, light verb structures featuring (

il)

fait display a stark contrast, with NSs representing only 15.38% of instances. Finally, impersonal (

il)

arrive sentences and fixed expressions such as

s’(

il)

vous plaît and (

il)

vaut mieux present no significant differences with respect to (

il)

y a constructions (a Fisher’s Exact test yielded, respectively,

p = 0.433,

p = 0.531, and

p = 1). However, it is important to note that the results concerning these three structures should be interpreted cautiously due the already mentioned small sample size, which may impact the reliability and generalizability of the findings and warrant further investigation to validate these trends.

On the one hand, the results presented so far are in line with what has been found in previous studies (cf.

Section 4.1), in which

(il) y a and (

il)

faut constructions appear to be the most likely to occur with an NS, while other verbs present a lower frequency of NSs. On the other hand, our analysis identified a few instances of NSs occurring with verbs which, as far as we know, have not been mentioned in the literature. This seems to suggest that a definitive list of specific verbs allowing an NS in Colloquial French is far from being completed (if it ever will be) and that it might be more fruitful to look at the specific linguistic context which triggers the realization of an NS in a non-pro-drop language such as French.

In this respect, it is interesting to notice that the absolute majority of the expletive subjects identified in the corpus (1301, that is 72.72%) are those occurring in non-predicational copular sentences (

Den Dikken 2006a), namely the

ce in

c’est constructions. Please consider the following examples:

| (35) | a. | C’ | est | une | amie | à | moi |

| | expl | be.3sg | det.indef.f | friend f | to | pron.acc.1sg |

| | qui | m’ | avait | dit |

| | pron.rel.nom.1sg | cl.acc.1sg | have. pst.3sg | tell. pp |

| | ‘It’s a friend of mine who told me….’ | (Apéritif) |

| b. | Mais | c’ | est | vraiment | genial |

| | but | expl | be.3sg | really | brilliant |

| | ‘But it’s really brilliant!’ | (Montage) |

| c. | C’ | est | une | soupe | populaire | musulmane |

| | expl | be.3sg | det.indef.f | soup | common | Muslim |

| | ‘It’s a Muslim kitchen-soup.’ | (Auréane) |

| d. | C’ | est | pour | ça | qu’ | J’ |

| | expl | be.3sg | for | that | that | pron.nom.1sg |

| | disais | le | carton |

| | say.pst.impf.1sg | det.f | box |

| | ‘That’s why I said the box.’ | (Auréane) |

Interestingly, not a single one of this type of expletive has been omitted by speakers. This result may be explained by the fact that, while existential (

il)

y a constructions predicate the existence of the following entity, impersonal (

il)

faut sentences predicate a need, and (

il)

arrive sentences predicate possibility,

6 “

c’est” constructions are non-predicational in nature. In short, the different behavior shown by the two French expletives,

il and

ce, seems to show that the crucial factor for the licensing of NSs in Colloquial French is whether an expression is predicative in nature or not.

This proposal is supported by recent analyses in which the different (information) structural functions of the relevant expletives have been highlighted. In particular, we refer to

Frascarelli (

2010a,

2010b) and

Frascarelli and Ramaglia’s (

2013) works on (pseudo-) clefts and existential ‘there’ sentences.

Trying to briefly set out a long and complex argument, in the above-mentioned works Frascarelli and Ramaglia consider specificational sentences as copular sentences, based on

Den Dikken’s (

2006a) influential proposal. As such, the structure of copular sentences implies a Small-Clause (SC) construction in which one of the two constituents specifies the value of the variable represented by the other. In this line of analysis,

Belletti (

2005) and

Frascarelli (

2010b) propose a monoclausal specificational study of cleft sentences in which the clefted phrase and the relative clause are merged as independent constituents within a SC. In particular, the clefted phrase is merged as the predicate, while the relative clause (i.e., presupposed information) can be assumed to play the subject role.

Hence, a cleft sentence can be described as a Focus-Presupposition structure (

Krifka 2006), including a copular element, a focused constituent (i.e., the clefted phrase), and a subordinate clause.

| (36) | It is a book that I gave John |

| COP [SC [DP that I gave John] [DP a book]] |

Frascarelli and Ramaglia (

2013,

2014) took this proposal, and based on syntax–prosody interface evidence, proceeded a step further in the analysis of specificational sentences, showing that the relative clause should be analyzed

as a Topic. Specifically, in line with

Frascarelli and Hinterhölzl (

2007), the authors assume that Topics must be distinguished according to their formal and discourse properties and that different types of Topics are located in dedicated functional projections in the (split) C-domain. As the relative clause in a cleft sentence is associated with a [+given] semantic property, it qualifies as a so-called ‘Familiar Topic’. As such, it is subject to Merge in the lowest left-peripheral Topic position (FamP) and is realized with a deaccented prosodic contour. Its final right-peripheral position is derived through IP-inversion to the Spec position of the Ground Phrase (GP; cf.

Poletto and Pollock 2004; for details, cf.

Frascarelli 2007).

The derivation of a sentence like (38) is thus the following (please, note the position and the co-indexing of the expletive

it, highlighted in bold):

7| (37) | a. [GP [FocP [TopP [DP OPk that I gave John ek ] z [IP is [SC itz [DP a book]]]]]] → |

| b. [GP [FocP [DP a book]k [TopP [DP OPk that I gave John ek]z [IP itz is [SC tz tk]]]]] → |

| c. [GP [IP itz is [SC tz tk]] [FocP [DP a book]k [TopP [DP OPk that I gave John ek]z tIP ]]] |

As can be seen, in this line of analysis the subject pronoun

it in the SC

is not an expletive but

a resumptive pronoun of the right-hand topicalized relative DP, which is merged as the subject of the SC (39a) and moved to Spec, IP (39c). A final note concerns the copula, which, according to this approach, has no semantic content (also cf.

Stowell 1981). It is just a functional element (i.e., a “linker”; cf.

Den Dikken 2006b) of the two major constituents of the sentence, triggering the movement of its complement to the Spec position.

To conclude, according to this semantic and IS-approach that we assume, specificational constructions are realized as copular sentences in which new information serves as the predicate of a SC, and the presupposed part of the sentence is topicalized and resumed by a subject pseudo-expletive pronoun in the subject position.

Given this resumptive function, the subject of a specificational sentence (i.e., ce in French) is not an expletive but a referential pronoun, and as such, it can be hardly silent in a pro-drop language like French. This proposal provides a feasible explanation for the fact that the pronoun ce is always present in the corpora examined. As a matter of fact, even when a co-indexed Topic is apparently not realized, it is in fact present, albeit silently, as it can be deduced from the context (it can thus refer to something being talked about, as in the case of sentence (37b) above).

On the contrary, the expletive il in predicational sentence is indeed an expletive pronoun, which is merged in the subject position because no argument can move there to meet EPP requirements. In particular, this happens when the theme argument is propositional (hence, too ‘heavy’ to move in subject position, as with a raising verb like seem in English), or in presentational sentences, in which new information is a theme selected by the verb. This is exactly the case of the expletive il in il y a constructions in French.

Indeed, the French language has maintained the proto-Indo-European form of existential sentences, so that what is now generally realized through the auxiliary

be, it is still realized in the original ‘have+LOC’ form (cf.

Freeze 1992).

Following

Den Dikken (

2006a), the basic difference with respect to specificational sentences is that existential constructions are analysed as copular structures of the predicative type and, as such, characterized by the non-referentiality of the second nominal. The locative argument is realized in the VP through a cltitic pronoun (ci in Italian and y in French; also cf.

La Fauci and Loporcaro 1997), which is co-indexed with the topicalized locative constituent. The expletive pronoun (

there in English and

il in French), does not consequently have an anaphorical function and is only inserted to meet the EPP requirement and predicate the

property of the first nominal (its subject; cf.

Ramaglia and Frascarelli 2019 for details).

The basic semantic and informational distinction characterizing expletives in specificational and predicational sentences can be thus feasibly assumed to be the explanation for their different behaviour and allow for a principled distinction of expletive drop in a non-pro-drop language like French.

As a final support to this proposal, it can be noticed that expressions such as s’(il) vous plaît and (il) vaut mieux can be considered examples of phrasemes, namely fixed expressions whose meaning is not directly derived from the meanings of their individual components. In these expressions, the expletive il does not contribute an independent semantic value to the overall meaning of the expression but is instead part of a formulaic structure that expresses a particular meaning as a whole. It can thus be argued that this lack of individual semantic contribution makes the presence of the subject il optional or redundant, thus contributing to its omission. This semantic distinction across syntactic structures underscores the complex interplay between formal realizations, semantics, and discourse in the possibility of subject omission, even in a non-pro-drop language like French, shaping the distribution of the Null and overt Subjects observed in the analysed data.

6.2. Referential NSs

As mentioned at the beginning of

Section 6, out of 3207 referential subjects found within the sub-corpus, only 29 are null. Specifically, three types of referential NSs have been identified, namely, canonical NSs (cf.

infra) (38a), NSs within repetitions (38b), and NSs referring to an extra-linguistic entity (38c). As can be seen in

Table 4, the absolute majority of referential NSs are canonical NSs, while only a few cases of the other two types have been identified.

In order to provide a comprehensive analysis of each of the above-mentioned types of NSs, let us now turn to some illustrative examples from the sub-corpus.

| (38) | a. | Celui | sur | le | pont | là | je | ne | sais | plus |

| | the one | on | det | bridge | there | I | not | know.1 sg | more |

| | comment | pro | s’appelle | |

| | how | (he) | be.named.3sg | |

| | ‘The one on the bridge there, I don’t know his name anymore’ | (Auréane) |

| b. | Ils | attrappent… | ouais. | pro | attrappent | des | maladies |

| | they | catch.3pl | yeah | (they) | catch.3pl | some | disease.pl |

| | pas | possibles | |

| | not | possible | |

| | ‘They catch… yeah. They catch some impossible diseases’ | (Apéritif) |

| c. | pro | se cache | sous | les | meubles | |

| | (it) | hide.3sg | under | det | furniture.pl | |

| | ‘It hides under the furniture’ | (Montage) |

As can be seen in (38a), the speaker omits the subject of the verb

s’appelle, which is a third person pronoun coreferent with the entity introduced at the beginning of the sentence (i.e., Celui sur le pont ‘the one on the bridge’). This is a ‘textbook example’ of how NSs occur in consistent pro-drop languages (hence the label ‘canonical’), in that the third person NS is linked via Agree to the DP

Celui sur le pont là which is a specific type of Topic heading a Topic chain (i.e., the A-Topic, cf.

Frascarelli 2007). In (38b) the speaker overtly realizes the subject of the verb

attrappent but then he hesitates and starts again the sentence, omitting the subject that would have been exactly the same. Finally, with the sentence in (38c), the speaker suddenly interrupts his interlocutor, who is talking about something else, referring to a cat that is present in the extralinguistic context, without realizing the relevant overt subject pronoun.

In all these examples, the omitted subjects are linked to a referent that is strongly active in the current discourse context, since they have been introduced as a Topic (38a), uttered mere seconds before (38b), or they are literally in front of the speaker’s eyes (38c). Be that as it may, in these cases subject omission can be explained by the presence of an A-Topic, either explicitly introduced as in (38a-b) or silent as in (38c), which establishes an Agree relation with the sentential subject and thus enables speakers to omit it. This result is coherent with what has been proposed in previous studies (cf.

Section 4.2), since the A-Topic, which is linked to a canonical NS (cf. 39a), is indeed a left-dislocated prosodically strong constituent. What is more, our analysis suggests that these dislocated constituents may not only be pronouns, but full DP as well (e.g.,

Celui sur le pont là).

In the light of these results and relevant reflections for proposals, it can be now interesting to consider a comparison with another non-pro-drop language. And, this is what we are going to do in the next section, in which a comparison with English will be proposed using the results reported in

Cote’s (

1996) spoken corpora investigation.

6.3. Null Subjects in Non-Pro-Drop Languages: A Comparison Between English and French

Even though different scholars have dealt with subject omission in non-pro-drop languages, focusing on specific contexts of realization, very few works have been systematically dedicated to the possibility and the properties of NSs in a single non-pro-drop language. Among these few studies,

Cote’s (

1996) work on NSs in English represents a precious point of reference for an effective comparison, since relevant results are based on the systematic investigation of a corpus of spoken data.

In particular, Cote used some 10 per cent of the Switchboard Corpus (telephone conversations performed by pairs of native speakers of English adults aged 20–40 on a variety of everyday topics), thus collecting a total of 190 NSs (out of 243 conversations), which have been examined taking into consideration several factors: (a) the form of the subject, (b) the person/number of the subject, (c) the source of the subject (i.e., whether it is referential, deictic, discourse deictic, or expletive), (d) the so-called “centering” transition of the utterance, (e) the turn position of the utterance (i.e., either initial or final), (f) the discourse segment position of the utterance, and (g) the clause type and the sentence type.

Turning to results, it is interesting to notice that the most frequent type of NSs in Cote’s corpus of English conversations is not that of expletives, but of referential pronouns (63%). Indeed, null expletives are only 37% of total NSs. However, even if null expletives are not as frequent as in French, they are still much more frequent than their explicit realization even in English, which, in fact, are only 8.9% of total expletive subjects.

Unfortunately, since the author was mainly interested in the discourse-related aspects of subject omission, no specific distinction is provided between expletives. Therefore, no one-to-one comparison can be carried out with respect to our French data. On the other hand, an interesting comparison can be provided between expletive and referential NSs. Indeed, the omission of 1sg and 3sg pronouns appears to be rather frequent in English phone calls, which is contrary to French face-to-face conversations. In particular, null 1sg deictics reach 26% of the total NSs and null 3sg referential pronouns reach 16.6%. In this latter case, it might be interesting to notice that null third person referential subjects were noticeably lacking in animate referents: only 3 out of 30 examples referred to animate entities.

As for discourse-related factors, in

Cote (

1996) it is reported that 32% of the referential NSs referred to the same entity as did the subject of the previous utterance. Notably, referential NSs in English were mostly used in a continuing function (26.3%); consequently, they served as Given Topics in Topic chains.

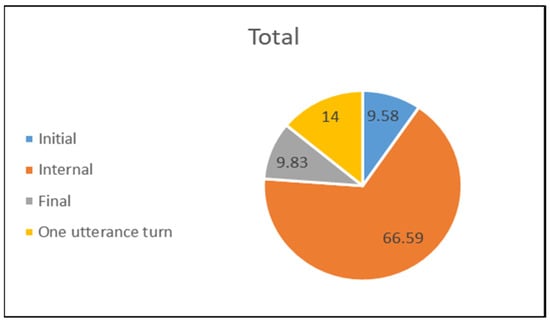

As far as their position in the sentence is concerned, Cote’s data show that the NS utterances occurred much more frequently in one-utterance turns (38.9% for NSs vs. 6.42% for overt pronominal subjects). Specifically, it seems that NSs in English tend to occur at discourse boundaries (i.e., turn-taking boundaries), while they are rare turn-internally (21.1%). Hence, their function seems to be that of marking a discourse boundary. In this respect, the situation that emerged from our corpus research on Colloquial French is completely different: NSs occur in one-utterance turns only in 14% of total cases and their position is eminently internal, as is shown in

Table 5 and the corresponding figure (

Figure 1).

The dominant preference of NSs for an internal position does not make great distinctions between referential and expletive pronouns, as is shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7 and the corresponding figures (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Indeed, as can been seen in

Table 7 and

Figure 3, the percentages attested for the (

il)

y a construction (which represents the most frequent realizations for expletive NSs in the corpus examined) show that expletive NSs also prefer an internal position.

In light of the present comparison, we can thus confirm that subject omission is possible in non-pro-drop languages and it is neither sporadic nor occasional. In particular, expletives appear to be the most frequently omitted type of pronouns. Nevertheless, a crucial distinction emerges between French and English, according to which the omission of referential subjects seems to be significantly more frequent in the latter.

Nevertheless, we surmise that this distinction can be attributed to the different context of conversations examined in the relevant corpora: face-to-face (French) vs. phone call conversations (English). Indeed, it is plausible to suppose that a phone conversation between two persons is dedicated and thus concentrates on some specific entity which is taken as the Topic of the relevant discourse and maintained as continuous, somehow “stimulating” its repetition across sentences. On the other hand, Topics can vary during a conversation among friends or be missing while building a piece of furniture.

Of course, these are just feasible assumptions which need to be resumed and confirmed in future comparative studies.

6.4. Coalescence: Corpus Support for a Restricted but Highly Frequent Phenomenon

A side note is reserved in this section to highlight the high frequency of morpho-phonological reduction phenomena occurring in conjunction with specific person–verb inflection associations. We refer to the incorporation of the 1sg subject je into the following verb, with the consequent creation of a single lexical form, with related morpho-phonological changes.

Consider the following sentences and the morpho-phonological realization of the subject–verb sequence (IPA transcription in square brackets):

| (39) | Moi | j’suis[∫ɥi] | pas | sûr | qu’ | elle | aille |

| pron. 1sg | 1sg.cl-be.1sg | neg | sure | that | pron. 3sgf | have.sub.3sgf |

| trop | avec | les | meubles |

| much | with | the.pl | furniture |

| “I’m not sure it goes too well with the furniture” (Apéritif) |

| (40) | Moi | j’ | trouve | ça | intéressant | parce-que | moi |

| pron. 1sg | 1sg.cl | find.1sg | it | interesting | because | pron. 1sg |

| j’suis[∫ɥi] | vraiment | nulle | en | géo |

| 1sg.cl-be.1sg | really | nothing | in | geography |

| “I find it interesting because I’m really bad at geography” (Apéritif) |

| (41) | Chomsky | j’suis[∫ɥi] | un | specialiste | de | Chomsky |

| Chomsky, | 1sg.cl- be.1sg | a | expert | of | Chomsky |

| “Chomsky, I’m an expert of Chomsky” (Apéritif) |

| (42) | Julie | je sais[∫ɛ] | pas | qu’ | elle | va | prendre |

| Julie, | 1sg.cl know.1sg | neg | what | pron. 3sgf | go.3sg | take |

| “As for Julie, I don’t know what she’s going to take” (Apéritif) |

| (43) | Je sais[∫ɛ] | pas | pourquoi | j’ | ai | pas | très | faim |

| 1sg.cl know.1sg | neg | why | 1sg.cl | have.1sg | neg | much | hunger |

| “I don’t know why I’m not very hungry” (Apéritif) |

As we can see, in these sentences the 1sg subject (weak) pronoun

je is pronounced as part of the following verb (

suis ‘am’ or

sais ‘know’). This fact might be simply ascribed to the fall of the “obsolete”

e (/ə/

schwa), a well-known phenomenon in French, which is often mentioned among scholars and in grammars (also cf.

Abeillé and Godard 2021 among others). Nevertheless, based on its specific context of occurrence, we are rather inclined to consider it a particular case of consonant assimilation.

8Indeed, corpus analysis shows that this phenomenon does not occur for all the occurrences of the 1sg pronoun and that when it occurs assimilation proceeds in both directions. Specifically, the postalveolar fricative [ʒ] of the pronoun je determines a change in the place of articulation of the following dental fricative [s], which, in turn, determines the regressive assimilation of the voiceless quality, thus obtaining a postalveolar fricative [∫]. On the other hand, the mode of articulation (fricative) remains unchanged.

In such cases, it is therefore appropriate to refer to the notion of ‘coalescence’ (cf.

Zaleska 2020, among others); that is to say, it is a type of assimilation whereby two sounds fuse to become one, and the fused sound shares similar characteristics with the two fused sounds. Some examples in English include ‘don’t you’ -> /dəʊnt ju/ -> [dəʊntʃ u]. In this instance, /t/ and /j/ have fused to [tʃ]. /tʃ/ is a palato-alveolar sound; its palatal feature is derived from /j/ while its alveolar is from /t/. Another English example is ‘would you’ -> /wʊd ju/ -> [wʊdʒu]. There are examples in other languages, such as Chumburung where /ɪ̀wú ɪ̀sá/ -> /ɪ̀wúɪ̀sá/ becomes [ɪ̀wɪ́sá]—‘three horns’. In this case, /ɪ/ is retained in the coalescence and the rising tone on /u/ appears on the coalesced sound.

Resuming the cases of French illustrated above, corpus analysis shows that these realizations occur almost exclusively with the auxiliary être ‘to be’ and with the verb savoir ‘know’ (occasional occurrences have been found with je serre [∫ɛr] ‘I squeeze’ (1 out of 2) and je dis [ʒi] ‘I say’ (1 out of 1)). Nevertheless, though restricted to these verbs, their frequency is remarkably high: 95% for je suis (74 occurrences out of 83), and 73% for je sais (45 out of 70). Additional evidence that this phenomenon cannot be (solely, at least) attributed to the fall of the final schwa is provided by the presence of a few occurrences of the 2sg pronoun tu ‘you’ and the verb savoir ‘know’ (5 out of 9), obtaining [tɛ] from tu sais.

The type of verbs with which this phenomenon occurs seems to support what has been argued in recent works concerning the faster and clearer occurrence of variation phenomena with words of high frequency, as ‘to be’ and ‘to know’ undoubtedly are. In particular, in

Connine (

2004) it is claimed that the representation of auditory form includes explicit representations of the frequently heard variant. Listeners encode surface detail from the speech that they hear and develop lexical representations that match their experience. One consequence of this view is that theoretical accounts of phonological variant processing will be informed by corpus analyses and variant frequency statistics will serve a critical role in theory development for auditory word recognition.