Arsenic Mitigation Program Reduces Exposure for Well Users in Native Communities

Arsenic in drinking water is a public health issue that largely affects private well users in rural areas. A community-led program is addressing this issue in the Great Plains region of the U.S. Consuming excess arsenic can lead to increased risk of several types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Rural, Native communities in the Northern Great Plains region of the U.S. face greater arsenic contamination due to elevated levels in groundwater and a reliance on private wells rather than a filtered public water source. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Columbia University, and Missouri Breaks Industries Research, Inc. partnered with Tribal government in the Great Plains and Indian Health Service to establish the Strong Heart Water Study to develop and evaluate a community-led arsenic mitigation program for private well users. This study built upon the long-running Strong Heart Study that examined cardiovascular disease in these communities.

Participants in the water study were divided into two groups — one that received arsenic filters and arsenic health communication through a mobile health intervention and another that received the same but were also visited at home. Researchers compared the approaches to determine whether more information provided through in-home visits encouraged participants to use their filtered water more often and maintain the filters more effectively.

Researchers examined the effectiveness of the interventions by asking participants about their use of arsenic-safe water and testing urinary arsenic levels. The results of the community-led research study in Tribal communities, published in March 2024, describe the positive impact of the intervention. More participants decided to use filtered water for both cooking and drinking, and urinary arsenic levels were significantly reduced. There were no differences in arsenic-safe water use or urinary arsenic levels between participants who were or were not visited at home. These findings suggest arsenic mitigation programs with arsenic removal filters that use only mobile health strategies can be as effective as more intensive home visits.

Members of the research team. (Photo courtesy of Ana Navas-Acien)

“We believe this is the first randomized control trial in North America to evaluate a water arsenic mitigation program,” said Christine Marie George, Ph.D., professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and principal investigator of the study. “The results showed us the community-led intervention was successful even when promoted only with a mobile health intervention and therefore represents a scalable approach that can be delivered in numerous communities.”

Addressing Risk of Arsenic Exposure in Northern Plains American Indian Communities

An analysis of community members’ water found that more than a quarter of all wells tested in Northern Plains American Indian communities had arsenic levels above the EPA-recommended 10 μg/L limit. The Tribal-academic study enrolled participants exposed to arsenic levels above EPA’s limit and installed filters in participants’ kitchen sinks.

Missouri Breaks Industries Research, Inc., a research organization owned and led by American Indians, managed the study. Community member plumbers worked with the Tribal Housing Authority, in partnership with the Indian Health Service, to install the arsenic filters. Participants were also given a packet of information on arsenic exposure and the filter, including instructions on changing the filter at the end of its lifecycle.

The mobile health intervention was a series of three scheduled phone calls from a community member from Missouri Breaks Industries Research, Inc., who encouraged participants to use the filtered water and reminded them when to change the filter. The in-home visits included video testimonials. Phone calls and home visits happened periodically for several months after the study started. Video testimonials featured community elders and a tribal leader, all of whom were private well users, speaking about the importance of using filtered water for drinking and cooking.

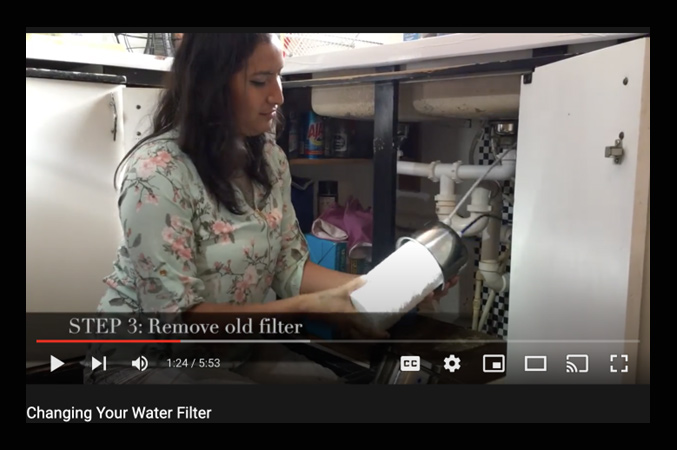

A video still from a video provided to participants to help maintain the filters. (Photo courtesy of Ana Navas-Acien)

“The challenge of mitigating arsenic in groundwater was more than just a technical endeavor—it was a commitment to our community,” said Tracy Zacher, the Project Director at Missouri Breaks Industries Research, Inc., and co-lead author of the study’s publication. “Leading this project required persistence, collaboration, and innovation to turn a hidden threat into a managed solution. Our work reinforced the power of science and dedication to protecting public health.”

Measuring Water Filter Intervention Effectiveness

At 6-months and 2-years after installing the arsenic filters, researchers surveyed participants on whether they used the filtered water for cooking and drinking. The researchers also collected urine samples throughout the study to measure participants’ arsenic exposure and used state-of-the art technology at the Trace Metals Core Laboratory at Columbia University to analyze the samples.

While there was a clear drop in urinary arsenic following the installation of the filters, there was no statistically significant difference between the intervention groups, indicating there was no added benefit of home visits.

There were also no statistically significant differences between the groups when surveyed on their use of arsenic-safe water, with similar increases in both groups for both drinking and cooking. Increases in use of arsenic-safe water were especially high for certain types of activities, such as making tea and cooking rice. Participants’ self-reported use of filtered water corresponded to lower urinary arsenic levels, showing that self-reported use of arsenic-safe water may be an accurate way to measure how participants use their water.

Overall, the study shows that reducing arsenic exposure is possible through installing arsenic filters and providing a mobile health intervention. Additionally, future use of the less resource-intensive strategy can have a positive impact on community members’ health. Zacher reflected, “The next steps in our work include refining solutions, strengthening community engagement, and ensuring long-term sustainability. Clean water isn’t just a goal — it’s a necessity — and our commitment remains unwavering in turning science into lasting change.”

Source link

www.niehs.nih.gov