(Photo courtesy of Cottonbro Studio from Pexels)

Researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) adapted an existing environmental justice index to characterize toxic metals from North Carolina drinking water wells. Their adaptation allowed inclusion of factors related to social disadvantage. A July 2022 paper describes their process. The authors state their new indices identified areas of potential environmental injustice from private well water contamination in North Carolina. In turn, results may be used to advance the provision of equal protection of communities against environmental hazards.

Drinking Water Supply as an Environmental Justice Issue in North Carolina

Households may rely on wells in areas not reached by public water supplies. These homes are often in rural areas; however, in North Carolina, historical practices excluded areas with a large racial minority population from the public water supply. Earlier in 2022, UNC researchers documented that thousands of wells throughout the state are contaminated with toxic metals.

Toxic metals of concern in North Carolina wells include arsenic, cadmium, manganese, and lead. Exposure to these metals is associated with various health issues, such as cancer, kidney impairment, poor cardiovascular outcomes, and neurological disorders. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets limits on the concentration of each of these metals in drinking water, which are only enforceable in public drinking water systems.

“Our previous research on private well water found thousands of tests with concentrations of arsenic, manganese, and lead, which exceed EPA limits,” stated Rebecca Fry, Ph.D., principal investigator of these NIEHS-funded studies. “Knowing about historical injustices, which excluded racial minority communities from public water supplies and have required them to use private wells instead, we wanted to examine how demographic factors relate to well contamination. This motivated us to develop the toxic metal environmental justice index.”

(Photo courtesy of Steve Johnson from Pexels)

Developing the Toxic Metal Environmental Justice Index

The index calculates the combined effects of socioeconomic disadvantages and environmental exposures. It includes two values that are also found in EPA’s EJScreen: a demographic index value based on census tract records, and an index representing environmental exposures—in this case, toxic metals in well water.

To determine the demographic value for each census tract, researchers compared the proportion of minorities and low-income households to the state’s overall minority and low-income populations. With this approach, census tracts with proportionally more minorities and low-income households than the state have a positive value, whereas tracts with fewer such households have a negative value.

To calculate the environmental exposure index, the researchers used their previously published NCWELL database, a compilation of more than 20 years of well water test results across North Carolina. The researchers used the database to determine how many tests per census tract exceeded EPA limits for arsenic, cadmium, manganese, and lead. The more contaminated wells per census tract, the greater the environmental exposure index value. When combined with the demographic index, a large positive value would indicate a census area with a high proportion of minorities or low-income households with greater well contamination.

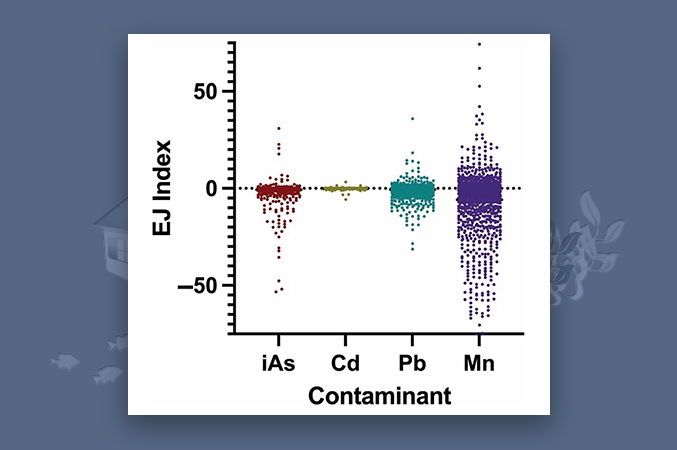

Using the Index to Determine Areas at Risk of Adverse Exposures

Researchers calculated index values for all census tracts throughout the state. They focused on areas with positive index values — areas with greater proportions of minorities and low-income households and high levels of metals in well water. They determined that most of the positive values are found in the eastern part of the state and in areas between urban areas and rural areas. Researchers then identified counties with the highest number of census tracts with positive environmental justice index values. Importantly, several counties were identified as having high levels of contamination by all four metals studied, indicating greater risks to those communities.

Results from the study showing the index values for all North Carolina census tracts for the four metals studied: inorganic arsenic (iAs), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and manganese (Mn). (Figure courtesy of study authors.)

“Our research focused on the values that showed areas where more low-income and minority communities live because we are interested in finding areas that may be suffering from environmental injustices,” clarified Fry. “We found that areas with a lower proportion of low-income and minority residents also experience high levels of well contamination, but the index can help show the need for support in areas with fewer resources to address contamination.”

Social disadvantages can make efforts for improving the quality of well water more challenging. For example, exposure to well water contamination can be mitigated by installing filters in sink taps in the home. However, the cost of such filters may mean they are not a realistic solution for many low-income individuals.

In the future, the researchers aim to further refine the index with updated census data and incorporate these data into the NC Enviroscan tool, which was developed by the UNC Superfund Research Program and key stakeholders in the community. The researchers hope that state and county officials will use the index to identify communities in need of remediation or further well testing to reduce residents’ exposure to toxic metals.

Source link

www.niehs.nih.gov