Measuring community members’ understanding of environmental health topics and self-efficacy to act on that knowledge can help researchers and educators better tailor interventions to meet the needs of communities. A team of NIEHS-funded researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Kentucky, and the University of Arizona, worked with residents who were concerned about their well water quality.

They developed an environmental health literacy (EHL) assessment instrument that is unique because it measures not only environmental health knowledge, but also factors that influence health behaviors. The scale examines residents’ beliefs in their ability to put knowledge into practice, or their self-efficacy, to reduce risk of poor health outcomes from contaminated well water. A September paper describes how this team developed and used the EHL instrument.

“We wanted to develop an instrument that went beyond knowledge assessment, to incorporate factors like self-efficacy,” stated Kathleen Gray, Ph.D., lead author and director of the Community Engagement Cores of the NIEHS-funded University of North Carolina Environmental Health Sciences Core Center and Superfund Research Center. “Self-efficacy data can provide greater context for understanding how people act on information about environmental health risks. When we started the study, beliefs were not incorporated into existing EHL instruments, giving us an opportunity to add that component.”

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Community Engagement Core members who lead community engagement and research translation activities. From left: Dana Haine, Andrew George, Ph.D., Kathleen Gray, Ph.D., Neasha Graves, Sarah Yelton, and Megan Lane. (Photo courtesy of Emily Williams)

Developing the Environmental Health Literacy Instrument

The researchers modeled their well water EHL instrument on a validated health literacy instrument called Newest Vital Sign. This validated instrument asks test-takers to review a nutrition label and answer a series of questions that examine how well they understand the label and nutrition concepts. Researchers similarly used a scenario-based format for the well water project, in which the scenario is a family deciding whether to use water that has arsenic in concentrations that exceed federal action levels. The EHL instrument contained four components:

- The hypothetical family scenario.

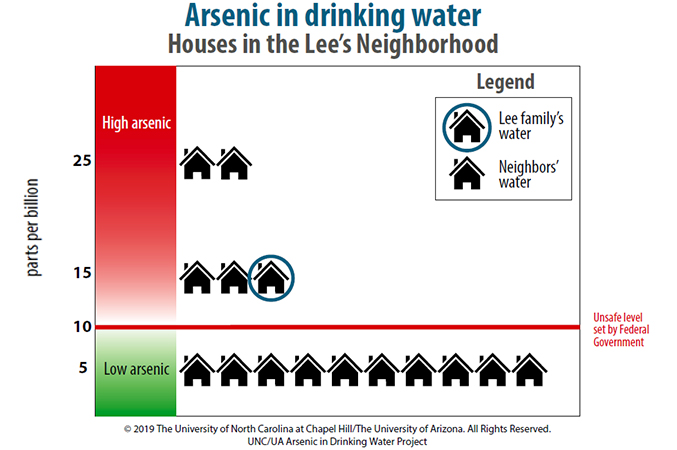

- A hypothetical report describing arsenic levels in the family home and in the neighborhood.

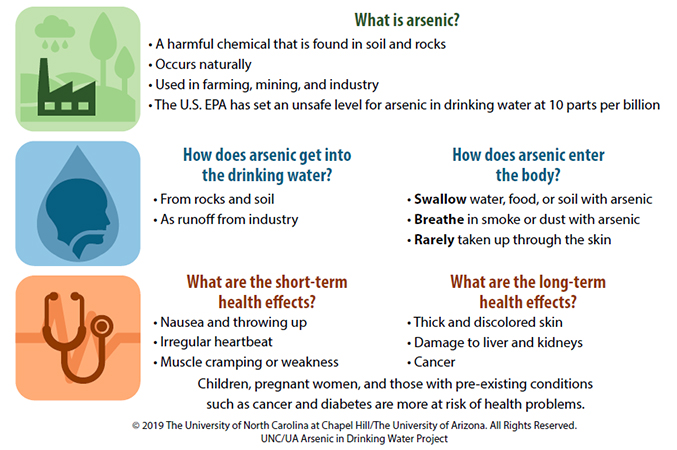

- A handout with information about arsenic and how it affects health.

- Questions focused on understanding of arsenic exposure and information-seeking behavior.

The hypothetical report of arsenic in the family home. (Photos courtesy of Emily Williams)

Handout with information about arsenic. (Photos courtesy of Emily Williams)

In addition to these four components, researchers also administered a self-efficacy survey which examined participants’ beliefs in their ability to test and treat well water and find environmental health information. For example, the survey asked about whether participants felt able to take the steps necessary to install a water filter in the home to remove contaminants.

“Researchers typically measure knowledge when assessing EHL, but information on other factors that influence behavior is also critical to understanding how people will respond when confronting potentially harmful environmental exposures,” added Gray. “The self-efficacy survey provided insight into participants’ beliefs in their ability to act on their environmental health knowledge.”

Testing the Environmental Health Literacy Instrument

Researchers tested the EHL instrument with 23 residents of communities with toxic metals contamination in well water and 24 undergraduate students who were not majoring in scientific disciplines. Researchers gave participants the scenario and report, and then participants answered a series of questions to examine how well they understood the environmental health concepts. Participants were then given a handout which provided information on arsenic and its health effects. After reviewing the handout, participants were able to answer the questions again. Additionally, by calculating EHL scores and comparing results with health literacy scores from the validated Newest Vital Sign instrument, the researchers gained insight into how EHL and health literacy may be related.

The instrument revealed differences in environmental health knowledge and self-efficacy between the community members and students. Students had higher EHL and health literacy scores, while community members indicated greater self-efficacy to take actions such as getting water test kits or installing filtration systems. These data were further supported by focus group discussions. While students demonstrated broader knowledge of environmental health topics in discussion, residents were better able to describe what they could do to reduce their risk of adverse health outcomes.

Researchers hypothesized that the differences between the groups may be related to greater lived experience among community members for whom the issue of arsenic contamination is more pressing. Residents may also have more resources than do students to purchase tests and filters. Additionally, higher assessment scores among students may reflect their active involvement in formal education, where testing is common.

“Tailoring interventions to communities’ needs is critical,” reflected Gray. “And as we seek to measure the impact of interventions, it is important to gather robust data that reflects what we know about behavior. Importantly, by including self-efficacy in our study, we demonstrated the value of considering how people would act on knowledge and key constraints to action. For well testing, financial resources and distance to travel to get well testing materials proved to be important constraints.”

Gray noted that another benefit of this project was the opportunity to expand the field of people working on EHL by involving young researchers and students.

“Working on this project was my first experience with research from start to finish,” said Victoria Triana, currently a student at the University of North Carolina’s Gilllings School of Global Public Health. “It solidified my decision to pursue a Master of Public Health, so I could gain further skills and continue to improve the accessibility of environmental health information for community audiences.”

The researchers continue to engage with communities concerned about arsenic exposure and seek to better understand how knowledge and beliefs interact to influence outcomes. For example, in a February 2022 paper, Gray and colleagues describe how residents implemented well water filtration and residents’ perceived barriers to doing so. The team hopes their work on EHL will lead to more effective educational interventions that ultimately reduce harmful environmental exposures among people who use well water.

Source link

www.niehs.nih.gov