1. Introduction

Despite efforts to improve energy efficiency, current solutions have limitations in choosing and implementing applications that fulfill these requirements. As a result, this study presents a comprehensive approach that integrates the sensing, communication, computing, and application layers. It utilizes a variety of heterogeneous devices and takes into account the structure and specific needs of different applications. This study outlines the model for the proposed solution and details its implementation. By using the software for planning, we expect that the project’s execution will lead to reduced energy consumption through better regulation of connectivity restrictions, resources, and equipment. Additionally, the software shows promise in supporting strategic planning and decision-making processes related to the modeled spaces, with the goals of cutting costs and promoting sustainability.

2. Related Work

Several studies have explored the role of emerging technologies in promoting energy sustainability and the evolution of IoT in manufacturing and service environments. Next, representative works are discussed to contextualize this paper’s proposal.

Although the works discussed offer significant advances in their respective domains, they exhibit limitations that this study aims to address. The majority of existing proposals focus on specific scenarios, such as manufacturing or short-duration events, neglecting the necessity for integrated solutions encompassing sensing, communication, computation, and application in heterogeneous industrial systems. Moreover, few studies have investigated the optimization of connectivity and resource constraints to reduce energy consumption in IoT architectures. This study addresses this gap and proposes an integrated approach to promote energy sustainability.

3. Proposed Modeling

The scenario unfolds as an optimization challenge, poised to maximize the overall utility of applications following the strategic deployment of IoT devices, edge servers, and network switches. Service utility is quantified through two essential dimensions: (i) coverage, which delineates the geographical scope where application events can be detected, and (ii) accuracy, which gauges the likelihood of accurately identifying those events.

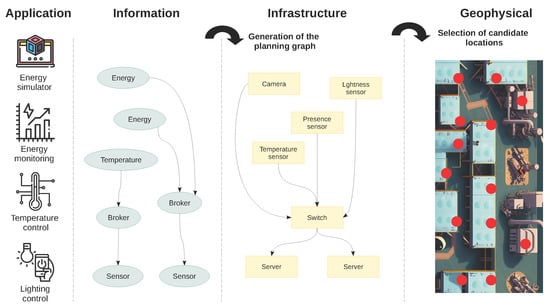

Crafting an effective deployment strategy demands adherence to a series of stringent constraints. These include financial limitations for installation and operation as well as considerations of detection ranges, computing capacity, network bandwidth, and quality-of-service (QoS) expectations. Tackling the intricacies of application planning is seen as a challenging task, given the intricate interdependencies among four vital layers: the application layer, tasked with executing services; the information layer, responsible for managing data processing and transmission; the infrastructure layer, which encompasses vital hardware resources; and the geophysical factors, which significantly impact deployment feasibility and efficiency.

In this complex landscape, the quest for an optimal solution promises enhanced performance and a transformative leap in harnessing technology for better outcomes.

The solution to be developed will serve as a differentiator compared to other energy efficiency promotion solutions. It aims to optimize the quantity of equipment and components needed while considering factors such as functionality and coverage.

The formulated model focuses on a manufacturing facility comprising multiple distinct rooms, denoted as

, where each individual room is represented by

. Within this industrial environment, a diverse set of applications

is required to support various operational tasks, with each specific application being identified as

.

The industrial environment is formally defined as a tuple

, where

represents the set of rooms, and

denotes the set of applications associated with each room

. For modeling convenience, each room is represented by the coordinates of its geometric center.

The facility consists of a set

of candidate deployment points, which include conventional infrastructure elements, such as lighting systems, air conditioning units, and computing devices, alongside IoT components like environmental sensors, edge computing nodes, and network communication equipment. These elements serve as potential locations for application execution and data collection.

Since different applications contribute variably to operational efficiency, each room

is assigned a weight

for each required application

, indicating its relative priority within that space. It is assumed—without loss of generality—that the sum of weights across all applications in a given room satisfies

,

. This weighting mechanism facilitates an optimized resource allocation strategy by reflecting the specific functional demands of each industrial zone.

Modeling must be conducted for an industry by considering all its rooms. Assuming the industry has 15 rooms, we can establish a model where

and

. Let us further assume that one of these rooms, specifically room

, is an administrative room that requires two applications: temperature control and consumption monitoring. In this case, we can represent these applications as

and

. Furthermore,

and

. This example is intended solely to illustrate the distribution of applications across rooms. The specific weight assigned to each application is detailed in the sections describing information and infrastructure flows, where factors such as coverage, accuracy, and resource allocation are considered. The model ensures that these weights reflect the relative importance of each application based on its functional role in the industrial environment.

The other elements of the model are described below.

3.1. Information Flows for an Application

Each application can be implemented using various combinations of sensor data from IoT devices and analytical algorithms on computing devices, such as edge servers. These devices are connected through directed graphs known as information flows. Different information flows for the same application enable planners to balance quality of service (QoS) with both deployment and operational costs. This allows for the selection of the most appropriate information flow to meet industry requirements.

, a set of information flows

can be adopted, with

being the k-th information flow. More precisely,

is a directed weighted graph where

denotes a unit of information, which may consist of raw data or components of the communication middleware, and

represents the data flow between these information units. Both the vertices and edges have associated weights. The weight of a vertex

indicates the computing resources consumed by that unit of information, while the weight of an edge

reflects the bandwidth consumption. Additionally, each information flow specifies the number of sensors needed; for example, three microphones are required for sound source detection using triangulation. Figure 2 illustrates how these information flows can be implemented in each application.

3.2. Infrastructure Flows Implementing an Information Flow

Each information flow can be deployed across various combinations of sensors, edge servers, and network switches, which are referred to as infrastructure flows. Different combinations of infrastructure flows associated with multiple information flows can result in varying levels of resource, or device, sharing. This allows for strategic planning to make use of resource reuse, leading to greater efficiency.

Each information flow

can be represented by a set of infrastructure flows

, where

denotes the m-th infrastructure flow. Let

be a directed weighted graph, where

represents a device and

represents the data flow between two devices. For our purposes, we consider various types of devices, such as sensors (for example, power meters or cameras), computing devices (like edge servers), and network switches (including LTE cells or Ethernet switches). The weights assigned to a vertex

and an edge

reflect the computing resources and network bandwidth they provide, respectively.

A tuple

encapsulates all information flows and their corresponding infrastructure flows for each application

.

Given a

and a

, each processing unit

is assigned to a device

through a specific function

. Additionally, for a given edge

,

represents the shortest path in

that includes the involved devices, reflecting the actual data flow at the infrastructure layer. For the sake of clarity, it is assumed that

contains at least one network switch unless devices

and

are identical. If processes u and v operate on the same device, their network bandwidth is significantly higher, leading to the assumption that

.

3.3. Planning Graph

Application deployment planning can be carried out by analyzing the flow of information and infrastructure. There are two types of deployments: (i) initial deployment, where no existing IoT infrastructure is in place (such as in a greenfield industry), and (ii) retrofit deployment, where IoT devices, edge servers, and network switches are already integrated (as seen in a growing industry).

An auxiliary structure known as a planning graph is created based on the following concepts. This planning graph is defined as a two-layer graph

: the first layer

consists of a set of information flows, while the second layer

comprises a set of infrastructure flows. In both layers, flows can share vertices and edges. Additionally, a set of assignment edges

is defined, where each edge

represents the assignment of

to

for

and

. This planning graph can be denoted as

and

.

3.4. Infrastructure Geophysical Mapping Function

To identify candidate locations, a geophysical mapping function

maps a vertex

from the infrastructure layer of a planning graph

to each candidate location

.

represents each device

. The device’s transmission range is denoted by

, while

indicates its detection range.

specifies the type of device, which can be either a sensor, a compute unit, or a network device. If

“network”, then

represents the transmission range of its associated network device u, denoted as

. Furthermore, multiple devices can be assigned to the same candidate location. For clarity,

is used to refer to the sensors of

(that is,

“sensor”). Figure 4 illustrates the geophysical mapping for an infrastructure flow. To identify candidate locations, a geophysical mapping function

will associate a vertex

of the infrastructure layer of a planning graph

with a potential candidate location

.

3.5. Utility of a Service in an Infrastructure Flow

is defined as

. By definition, the Euclidean distance between two two-dimensional points

and

is given by Equation (1):

; otherwise, the flow is deemed unconnected. If

is connected, the service utility in a room

is determined by Equation (2):

where

represents accuracy, while

signifies the probability of detection.

If

is not connected, then

is defined as 0. Each

that pertains to the application

includes a precision model

that varies based on the method used. For instance, detection based on presence sensors is generally more accurate for identifying presence than detection based on images.

, the probability is attenuated (or decayed) with increasing distance in

and truncated by its detection range

. Therefore, if

, the average truncated attenuated detection probability, denoted as Y, is expressed by Equation (3) as follows:

where

is a parameter that is related to v. If this relationship does not hold, then

.

3.6. Costs

Each device

in the infrastructure layer is subject to two types of costs:

- (i)

deployment cost

due to deploying the device v at the candidate location

, and- (ii)

operational cost

due to maintaining its operation.

The deployment cost charged once, while the operational cost is recurring. Furthermore, we define

and

as the budgets for deploying and operating the devices. The operational cost refers to the ongoing expenses required to keep the device functioning, such as energy consumption, maintenance, software updates, and other associated costs necessary for its continuous operation.

3.7. Problem Formulation

Given the industry’s operational characteristics, the interaction between information and infrastructure flows, and the constraints regarding resource availability, the energy efficiency planning problem seeks to optimize the overall quality of services while adhering to predefined cost budgets. The objective is to derive an optimal planning graph, denoted as

, and determine the corresponding geophysical mapping functions

that best allocate resources across the industrial environment.

and the corresponding geophysical mapping functions

that maximize the total utility of the system. This optimization process efficiently balances resource allocation, service quality, and energy consumption.

and the operational cost

. These constraints ensure that the deployment and ongoing management of the industrial infrastructure remain within financial feasibility.

, ensuring that its available computational resources are sufficient to process all assigned information units u. This constraint means that each device’s weight

must be at least equal to the cumulative weight of all associated processing tasks, preventing system overloads and performance degradation.

, Equation (10) enforces that the minimum bandwidth along the allocated communication path

meets or exceeds the required bandwidth threshold. This constraint is required to maintain reliable data flow across the industrial IoT network, support real-time applications, and minimize latency issues.

-hard optimization problem, which inherently resists approximation within a factor of

. This complexity can be established by demonstrating a polynomial-time reduction from the well-known max K-cover problem [27] to a constrained version of the energy efficiency planning problem.

-hard and has a polynomial reduction to this special case, the original energy efficiency planning problem retains the same computational complexity. Furthermore, as demonstrated by Feige [28], the max K-cover problem cannot be approximated within a factor better than

unless

. Consequently, this inapproximability threshold extends to the energy efficiency planning problem, reinforcing the inherent computational challenge associated with optimizing the energy efficiency under deployment and operational constraints.

4. Heuristic Solution

The smart space planning problem is decomposed into two subproblems targeting reducing complexity and avoiding redundant calculations: (i) geophysical mapping selection, which chooses promising mappings among infrastructure flows and candidate locations, and (ii) generation of planning graphs, which calculates mappings between information flows and infrastructure flows that maximize the overall service utility.

Let

denote the optimized planning graph, where

represents the set of information flows and

defines the infrastructure flows. This decomposition is essential because identifying the optimal planning graph requires the continuous generation and assessment of geophysical mappings associated with

. Since these mappings remain largely static, a more efficient strategy involves storing and reusing them rather than recalculating them at each step.

The first heuristic, SEL, is based on selection policies to eliminate less promising mappings. The policies contain the following intuitions: (i) MIFs with more significant utilities should be included earlier and (ii) MIFs with more excellent communication coverage should be included earlier.

, the utility can be estimated by Equation (2) after mapping all equipment (assuming that the graph is connected). Similarly, the communication coverage of a network device can be estimated after mapping. Algorithm 1 presents the adopted heuristic, using M and N to represent the user-specified pruning criteria for utility and communication coverage, respectively.

| Algorithm 1: SEL . |

|

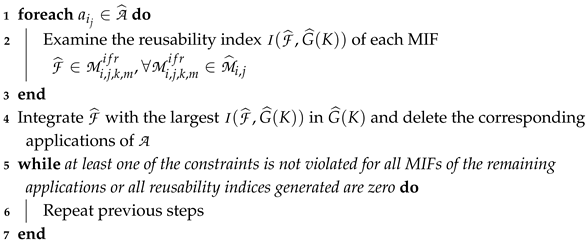

In the MR heuristic, instead of examining all possible combinations of MIFs, it iteratively (i) selects an application

to implement and (ii) merges an END

in the planning graph

according to the reusability of

, where

. A reusability index was defined, considering the investment efficiency and the gain in communication coverage when merging

.

into

. In other words, the more infrastructures are reused, the lower the costs will be with merging

. Specifically, whether we choose

, and considering the application’s utility gain after merging

into

, the cost gain is given by

which is the investment efficiency of merging

into

.

The current investment efficiency formula balances utility gain and costs in a structured industrial environment. However, we acknowledge that a more adaptive approach could be beneficial in environments with a highly variable application utility and resource costs. One potential adaptation would be introducing weight adjustments based on real-time demand fluctuations, prioritizing applications with a higher dynamic impact. Additionally, integrating cost prediction models could refine investment decisions by anticipating resource variations. Although this extension is not currently implemented, it represents a promising direction for future work, particularly for applications in heterogeneous or rapidly changing industrial contexts.

be the candidate locations in the communication coverage of network devices in

. The communication coverage gain after merging

into

is given by

into the intermediate planning graph

. Let

and

be the weights of the investment efficiency and communication coverage gain, respectively. The reusability index is written as

Without the loss of generality, it is assumed that

.

and iteratively selects an application

to implement by merging an END

in the current intermediate planning graph

(as established in Algorithm 2), where

.

| Algorithm 2: MR |

|

When viewing Lines 1 to 3 (Algorithm 2), for each application

, it can be seen that the algorithm examines the reusability index

for each END

within the set of possible mappings

, where

represents the set of all mappings for the considered application. In Line 4 (Algorithm 2), the END

with the highest reusability index

is then incorporated into the planning graph

. Applications corresponding to this END are excluded from the set

, indicating that their infrastructure needs have already been met.

The process repeats the evaluation and selection steps as long as at least one of the constraints is not violated for the MIFs of the remaining applications, or until all calculated reusability indices are zero. This strategy ensures that planning continues to optimize component reuse without violating operational or design constraints. As output, the algorithm produces a planning graph representing the infrastructure and application mapping, prioritizing component reuse.

To establish the convergence of our heuristic methodology, we validate two fundamental characteristics: (i) each successive step enhances the function

, and (ii) these enhancements gradually diminish, yielding convergence.

where

represents the utility of a selected infrastructure flow at room

, and

is a weighting factor for each application. The MR heuristic iteratively selects a FIM

that maximizes the reusability index. Since the heuristic always selects

such that it improves utility, it follows that

This characteristic guarantees that the efficacy function exhibits monotonic growth across iterations.

represent the utility gain at iteration t, defined as

is relatively large. However, as the number of remaining candidate FIMs decreases, additional selections yield redundancies due to overlapping mappings, reducing their incremental contribution to the utility. This behavior can be modeled as an exponential decay in utility gain as follows:

approaches zero as

, we conclude that

is both monotonically increasing and bounded above by the maximum achievable utility under budgetary and infrastructural constraints, the Monotone Convergence Theorem [29] guarantees that

converges to a finite value as follows:

Thus, we have established that the heuristic progressively achieves an optimal or near-optimal configuration, ensuring convergence while maximizing energy efficiency throughout industrial environments.

Implementation

The first component is the user interface, which is designed to enable modeling and planning. This interaction occurs through the REST API. User models were validated according to the specifications intended for IoT models. This process is based on standards and specifications developed to facilitate interoperability and simplified data exchange between devices and systems in IoT environments.

After validating the models, planning is performed using the heuristic solution described in the previous section.

In information and infrastructure flows, each node is assigned a role that specifies its role. Vertices can be classified as sensor, representing sensors or any data collection device, network for component parts of the network, or compute, indicating devices with processing capacity. For vertices categorized as sensors, attributes list the data types that a device can collect.

The attributes that were introduced were r_tr and r_sen, which represent the transmission range () and sensing range (), respectively. In addition, precision_model was introduced as a representation of the precision model

. The procedure starts by selecting all possible geophysical mapping functions for each room, considering the sensors whose sensing area includes part of the room. In this analysis, candidate locations in the room and external locations are considered, as long as the room is in the sensing coverage area of a sensor in these locations.

In the implementation, Shapely and Geopy libraries were used in Python 3.9. Shapely is used to manipulate and analyze plane geometry. It allows for the creation, manipulation, and analysis of geometries in addition to performing operations such as union, intersection, and difference on geometric objects. On the other hand, Geopy provides a simple and consistent interface for performing various geographic operations, such as geocoding, distance calculation between geographic points, and route calculation between locations. Moreover, it is often used in applications involving geographic data analysis, geolocation, and geocoding.

5. Performance Evaluation

The performance evaluation of our proposed smart space planning framework focuses on assessing the system scalability and cost-effectiveness in industrial environments. Using the simulated scenarios, we evaluated the efficiency of our IoT-based planning model. We employed a multifaceted evaluation that included scalability and cost-effectiveness analysis. By implementing optimized information and infrastructure flows, the system demonstrated consistent efficiency gains even as the number of deployed devices increased.

5.1. Setup

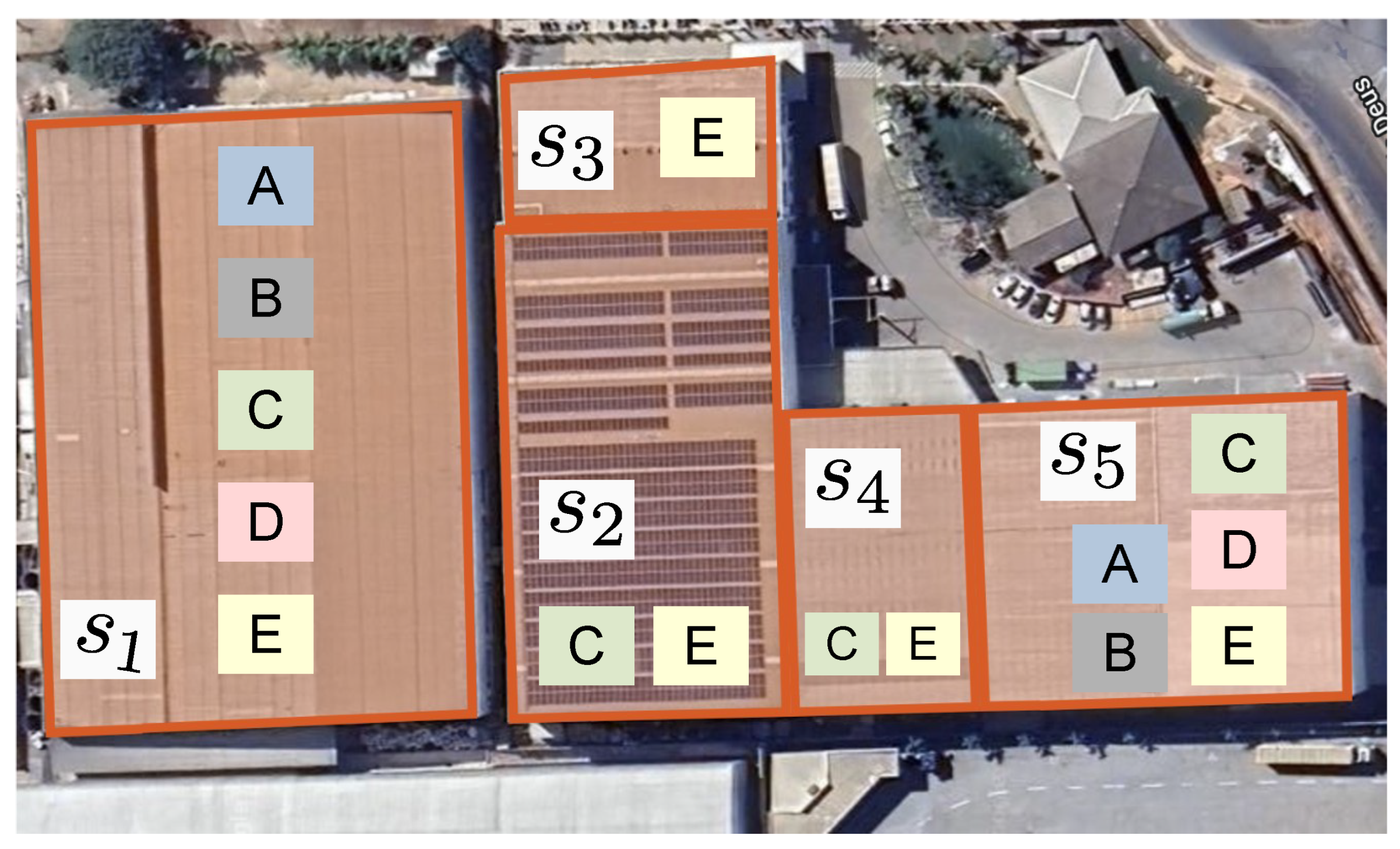

The experiments were implemented using a data generator to simulate data on industries and applications. The goal was to create a structured representation of the industry’s physical space and operational processes to simulate possible scenarios for using the proposed solution.

The total area of the specified physical space is divided into functional categories, such as production, offices, utility and storage, ensuring that the spaces are proportional to an industry’s typical needs. Each generated room has attributes, such as size, occupancy capacity, type of functional area, and geographic location.

Specific applications were also created for each room by considering the following possibilities: (A) detection of mechanical failures, abnormal vibrations, or compressed air leaks in industrial equipment through acoustic sensing; (B) monitoring of emissions in boilers and thermal processes through smoke sensing; (C) monitoring of the efficiency of ventilation systems through air quality sensing; (D) detection of overheating in machines or industrial processes through temperature sensing; and (E) lighting and cooling control through presence detection.

The experiment was modeled on a typical industrial setup, featuring functional spaces commonly found in industries worldwide. The physical plant was divided into five distinct rooms ( to

). The Brazilian case was utilized solely to demonstrate the applicability of the solution. This division aims to simulate the industrial environment in detail, reflecting the typical requirements for evaluating the proposed IoT solution. The rooms were categorized as follows:

- •

: Production Area: represents the majority of the space, housing essential industry production processes.

- •

: Storage Area: designated for storing materials and finished products.

- •

: Utilities’ Area: this area is intended for operational support, such as production support machines and general utilities.

- •

: Office: place dedicated to administrative and management activities.

- •

: Other Production Area: this area complements the production processes and may include specific production lines.

Specific IoT applications were simulated for each of these areas to meet the functional and operational demands of each space:

- •

and

(Production): Applications A (detection of mechanical failures, abnormal vibrations, or compressed air leaks), B (monitoring of emissions in boilers and thermal processes), C (monitoring of the efficiency of ventilation systems), D (detection of overheating), and E (lighting and cooling control).- •

(Storage): Applications C (monitoring of ventilation efficiency) and E (lighting and cooling control).

- •

(Utilities): Application E (lighting and cooling control).

- •

(Office): Applications C (monitoring of air quality) and E (lighting and cooling control).

where

- •

is the frequency in hertz (Hz);

- •

is the transmission rate in bits per second (bps);

- •

N is the number of bits transmitted per cycle (we assume it as 64).

Application deployment plan considered in the experiment.

Figure 8.

Application deployment plan considered in the experiment.

Parameters used in the experiments [24].

Parameters used in the experiments [24].

| Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Bandwidth consumption | Image | 10 Mbps |

| Motion sample | 1.92 Kbps | |

| Emission reading | 0.64 Kbps | |

| Sound | 128 Kbps | |

| Computing resource requirement | Image | 1.25 MHz |

| Motion sample | 60 Hz | |

| Emission reading | 20 Hz | |

| Sound | 6 KHz | |

| Memory requirement | Image | 1.25 GB |

| Motion sample | 240 B | |

| Emission reading | 80 B | |

| Sound | 16 KB | |

| Computing resource | Edge server | 6.8 GHz (4 × 1.7 GHz) |

| Transmission range and bandwidth | WiFi AP | 50 m/100 Mbps |

| Lora gateway | 1 km/50 Kbps | |

| Sensing range | Camera | 15 m |

| Motion sensor | 10 m | |

| Gas sensor | 600 m | |

| Microphone | 300 m | |

| Sensing parameter in Equation (3) | All sensors | Reciprocal of sensing range |

The proposed solution was developed to be geographically neutral, relying on universal energy efficiency principles and IoT deployment. This neutrality ensures that the solution can seamlessly adapt to industries with varying infrastructural, economic, and regulatory conditions. Therefore, this Brazilian case study served as an illustrative example, and the model can be readily applied to other regions, supported by its modular and flexible architecture.

The experiments were conducted by varying the following parameters: (i) number of applications per room, (ii) number of information flows per application, (iii) number of infrastructure flows per information flow, (iv) deployment and operation budgets, and (v) MR weights to study their implications on various performance metrics.

5.2. Experimental Results

= 1 and

= 0. In this configuration, the covered location metric does not reach a value of 5, whereas all other weight configurations manage to reach or exceed this value. This result indicates that the system’s ability to expand the served geographic area by exclusively prioritizing efficiency over coverage, which is limited even with increased flows. Furthermore, as the number of flows increased in this specific configuration, the number of covered locations increased at a steadier pace than in the other weight configurations. This behavior suggests that, even under the exclusive prioritization of efficiency, the flow increase still contributes to expanding coverage but is less effective. The absence of weight attributed to coverage limits the impact of new flows on the expansion of the served geographic area. In contrast, in configurations where

has positive values, the system can simultaneously optimize efficiency and coverage, achieving higher values for covered locations. This result occurs because the weight attributed to coverage directs resources to expand the system’s performance geographically, maximizing utility and the area served.

The experimental results indicate that the proposed model demonstrates scalability to a certain extent, particularly regarding the increasing number of deployed devices and their impact on cost, utility, and coverage. The heuristic-based approach optimizes resource allocation, ensuring efficient device reuse while minimizing redundancy. However, we acknowledge that the scalability assessment did not cover all potential factors, such as extreme increases in the number of rooms or highly heterogeneous industrial environments. Nevertheless, given that the solution is designed for planning within a specific industrial context, we do not anticipate scenarios requiring an exceptionally high number of rooms. The model primarily focuses on optimizing the energy efficiency within predefined industrial spaces rather than handling large-scale deployments across multiple facilities. Future work could explore adaptations to enhance scalability for broader applications beyond the targeted industrial setting.

6. Final Remarks

One of the primary motivations for the solution presented in this work was the increasing complexity of challenges related to energy production, distribution, and consumption. The solution seeks to contribute to the energy efficiency in smart spaces in the context of Industry 4.0. The global demand for solutions that combine sustainability and technological innovation requires models capable of integrating advanced technologies, such as the IoT, artificial intelligence, and cloud computing, to promote more efficient, connected, and resilient industrial operations.

In this scenario, this study presented an adaptation of the SmartParcels framework, which constitutes an integrated model for planning smart spaces, combining sensing, communication, computing, and application layers. The model allows for the optimization of resource utilization and for maximizing the utility of services, respecting cost constraints and ensuring high energy efficiency. Specific heuristics were used to select promising geophysical mappings and maximize the reuse of devices, promoting economic and environmental sustainability. The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed solution is scalable and viable for large-scale applications across diverse industrial contexts. By not assuming region-specific characteristics, the model ensures adaptability to different industries and geographical regions.

Our analysis reveals that implementing a structured methodology for selecting information and infrastructure flows as well as heuristic-based optimization techniques yields substantial efficiency improvements. These insights provide valuable practical guidance for manufacturing, logistics, and industrial automation sectors navigating the transition to Industry 4.0 paradigms. Using our approach, the strategic allocation of IoT devices demonstrates multiple tangible benefits: (i) reduced energy consumption across industrial systems, (ii) minimized infrastructure expenditure, and (iii) enhanced system scalability for future expansion.

The results suggest that organizations can apply these methodologies to achieve optimal resource utilization while maintaining operational effectiveness. This balance between efficiency and performance represents a critical consideration for industries seeking competitive advantages in increasingly digitized operational landscapes.

However, some challenges pave the way for future work. It is important to note that the proposed solution focuses exclusively on the planning phase of smart spaces, specifically the design and deployment of IoT infrastructure to optimize energy efficiency. It does not address tasks or costs associated with the real-time execution of applications within these spaces, which remains outside the scope of this work.

Additionally, the model does not differentiate between constant and variable energy consumption scenarios. For example, energy usage in production areas may vary depending on production volume, while offices and utilities typically exhibit more constant consumption patterns. Future research should incorporate these dynamic factors to improve the model’s applicability to real-world industrial contexts. Furthermore, the model could be adapted to various sectors, such as precision agriculture, healthcare, and transportation, expanding its applicability and relevance. Another possibility would be to incorporate algorithms based on machine learning or artificial intelligence to improve the accuracy and adaptability of planning decisions, especially in dynamic scenarios with high device heterogeneity.

Additionally, validating the model in real industrial environments is essential to confirm its robustness and ability to meet complex demands. Such validation would enable a deeper analysis, including statistical hypothesis testing and sensitivity analyses, which are not feasible within the current simulation-based framework. This analysis could involve case studies in diverse industries, providing insights into operational efficiency, sustainability gains, and return on investment while addressing dynamic energy consumption patterns.

Finally, creating more intuitive interfaces and visualization tools could facilitate the model’s adoption by multidisciplinary teams, promoting its integration into strategic decision-making processes. Thus, this work lays the foundations for developing even more advanced solutions aligned with contemporary demands for innovative, sustainable, and efficient industrial operations.

Source link

Viviane Bessa Ferreira www.mdpi.com