3. Results

Between January 2015 and January 2024, we included 207 patients with 231 synovial fluid aspirations of the hip. The demographic characteristics of the included cases are shown in

Table 1. Twelve patients had synovial fluid aspiration within three months of onset of symptoms. These patients were considered suspected acute infections; all other patients had chronic symptoms. Revision surgery was performed in 212/231 cases. In 19 cases, tissue biopsy tissue cultures were taken, but no revision THA was performed.

In 197/231 cases, synovial fluid aspiration provided diagnostic information. In 193 cases, synovial fluid aspiration cultures were available. In four cases, synovial fluid white blood cell count and % PMN were determined but no synovial fluid cultures were taken.

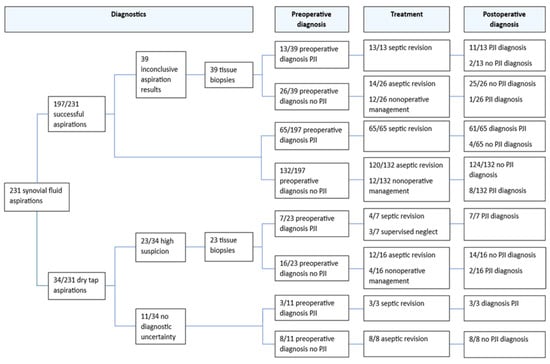

In 40/193 (21%) cases, aspiration cultures were obtained after flushing the hip joint with NaCl after an initial dry tap aspiration. In 34 cases, synovial fluid aspiration resulted in a dry tap (

Figure 1). Synovial fluid aspiration cultures had a sensitivity of 76% (95% CI, 65–85%) and a specificity of 98% (95% CI, 94–100%) for diagnosing PJI. In 81 cases, the number of leukocytes and the percentage of PMN leukocytes in the synovial fluid were determined. The sensitivity, specificity and predictive values are shown in

Table 2.

Tissue biopsy cultures were obtained in 62 cases. The sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of all 62 tissue biopsy cultures are shown in

Table 2. In 23 cases, biopsies were taken after dry tap aspiration, and in 39 cases because of an inconclusive aspiration result outcome. In 16/23 dry tap cases, subsequent revision surgery was performed. We found a sensitivity and specificity of 44% (95% CI, 17–75%) and 93% (95% CI, 72–100%), for tissue biopsy cultures after dry tap aspiration,

Table 3. In 4/23 cases, tissue biopsy cultures confirmed the clinical suspicion of PJI and changed the treatment strategy. In two of these four cases, septic two-stage revision arthroplasty was performed and in two cases supervised neglect was chosen as the treatment strategy.

Thirty-nine biopsies were taken after an inconclusive aspiration results outcome. Tissue biopsy cultures after an inconclusive synovial fluid aspiration led to a change in the diagnostic result in 7/39 cases. In 4/7 cases, tissue biopsy cultures confirmed PJI after a previous negative synovial fluid aspiration; these cases were considered septic and treated as such. In 3/7 cases, tissue biopsy cultures were negative after a previous positive synovial fluid aspiration. These cases were considered aseptic and were treated as such.

Culture results can be found in

Table 4. Similar microorganisms were found in synovial fluid aspirations and intraoperative tissue cultures, while the tissue biopsy cultures only yielded low-virulent pathogens. The most common microorganisms were coagulase-negative staphylococci. The same causative pathogens were found in all tissue biopsy cultures and in the intraoperative tissue cultures.

In 212/231 cases, intraoperative tissue cultures and sonication fluid cultures were available. The sensitivity, specificity and predictive values are shown in

Table 2. In 3/13 cases with a false negative result, antibiotics were prescribed within two weeks prior to surgery. In 19 patients, after informed consent, a nonoperative treatment was chosen, and revision tissue cultures are therefore not available.

4. Discussion

This study evaluates the diagnostic value of synovial fluid aspirations, and the addition of preoperative biopsies after inconclusive aspiration results or dry tap aspiration of the hip prior to revision THA in patients with a clinical suspicion of PJI. The sensitivity and specificity of biopsies after dry tap aspiration were 44% and 93%. The corresponding PPV and NPV were 80% and 72%. In 16/23 cases with a suspected PJI, tissue biopsy cultures refuted the PJI suspicion after dry tap aspiration and subsequently directly changed the patients’ treatment to an aseptic regimen. In 7/23 patients, PJI was confirmed (

Figure 1).

In addition, better diagnostic information, by identifying the causative microorganism and its antibiotic sensitivity through a tissue biopsy, can lead to a well-informed decision between one- and two-stage revision surgery as a treatment strategy [

14]. A septic one-stage revision may lead to improved functional outcomes compared to a two-stage approach [

15,

16]. In 7/39 cases, additional tissue biopsy cultures led to a change in treatment strategy after an inconclusive synovial fluid aspiration. The change in treatment strategy concerned both aseptic-to-septic revision and vice versa.

Studies by Fink et al. found a sensitivity and specificity of 82–94% and 94–98% for preoperative biopsies prior to revision surgery [

17,

18]. In these studies, a preoperative biopsy was performed in every revision case, not only in cases with dry tap synovial fluid aspiration. A study by Sconfienza et al. describes the diagnostic value of preoperative biopsies after dry tap aspiration. They performed ultrasound-guided, percutaneous periprosthetic biopsies in 40 patients after a dry tap aspiration. A sensitivity and specificity of 42% and 100% was found [

19]. However, during the biopsy procedure in this study, only one culture was taken. A study by Ottink et al. describes the diagnostic value of biopsies obtained in the operating room with a thick-bore needle in patients with a suspected chronic PJI. Twenty-nine tissue biopsies were included which led to a sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 100%. In the study by Ottink et al., tissue cultures obtained during revision surgery were used as the gold standard, which differs from our study [

20]. This may explain the difference in sensitivity between the studies. Simon et al. described the diagnostic value of biopsies after a negative joint aspiration culture or a dry tap in patients with suspected low-grade PJI, and found a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 69% [

21]. Their conclusion was that biopsies have a limited predictive value for diagnosing PJI. However, there were only six cases with dry tap aspiration and the authors fail to notice the percentage of patients in which the addition of tissue biopsy cultures caused a clinically relevant change of treatment.

Tissue biopsy cultures had a low sensitivity. The use of antibiotics prior to a preoperative biopsy is a common reason for a false negative result [

22]. Tissue cultures can be unable to reliably detect microorganisms that are embedded within a biofilm, which protects the infecting organisms from being recovered. Additionally, conventional cultures are frequently unable to grow low-virulent pathogens or fungi, leading to more false negative results [

23]. Tissue biopsy cultures only detected low-virulent bacteria (

Table 4). In our study, cases where antibiotics were prescribed within 2 weeks of culture collection were not excluded. This leads to lower sensitivity but approximates clinical practice.

In 39 cases, a biopsy was performed after a successful synovial fluid aspiration with an inconclusive result. These biopsies were performed when there was a discrepancy between the initial clinical suspicion of PJI and the aspiration results. In our study, biopsy cultures after an inconclusive joint aspiration changed the preoperative diagnosis in 7/39 cases. Hassebrock et al. described the role of repeat synovial fluid aspiration for diagnosing PJI. They found that a second synovial fluid aspiration additionally diagnosed PJI in 6/30 cases and ruled out PJI in 2/30 cases. Thus, a second joint aspiration accurately changed the preoperative diagnosis in 8/60 cases, which is lower than our findings [

24]. Furthermore, in the study by Hassebrock et al., a definitive preoperative diagnosis could not be made in 25/60 cases, based on the results of the joint aspirations [

24]. This is because only one culture can be obtained during hip aspiration and there is not always enough synovial fluid to perform all diagnostic tests. This suggests that subsequently taking tissue biopsies is a better option than repeat hip aspiration for diagnosing PJI in this specific group.

The sensitivity and specificity of synovial fluid aspiration cultures in our study were 76% and 98%. These results are in line with previous studies [

8,

25]. The meta-analysis of Qu et al. found a pooled sensitivity and a specificity of 70% and 94% [

25]. Similar results were found in the meta-analysis by Carli et al. [

8]. In 40/193 procedures, joint aspiration cultures were obtained after flushing the hip joint with sterile NaCl. The diagnostic value of cultures obtained after flushing the hip with NaCl is controversial. In the literature, a high sensitivity and specificity is described [

26,

27]. However, some studies did find a lower sensitivity when joint aspiration cultures were diluted with NaCl [

10,

28]. Since our results are consistent with the literature, we believe that the cultures obtained after flushing the hip joint with NaCl did not alter our results.

Synovial fluid analysis includes a leukocyte count and a calculation of the percentage of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs). A high number of leukocytes and a high percentage of PMNs (>3000 and >80% respectively according to EBJIS criteria) would be confirmatory of PJI [

6]. In our study, the results were only available in 81 patients, as the others had either a dry tap or an insufficient amount of synovial fluid for chemical analysis. The synovial fluid leukocyte count can introduce confusion, as there are other factors such as wear, metallosis, and rheumatologic disorders such as gout or pseudogout can cause a high synovial leukocyte count. Therefore, in case of a low-volume successful joint aspiration, we prefer to use it for culture rather than chemical analysis.

In recent years, several new diagnostic tools have become commercially available for the detection of PJI. Even though the results are promising, wide-spread adoption is still limited due to the relatively high costs of these tests [

29]. Molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing may be valuable additional diagnostics to detect PJI [

30]. A meta-analysis by Cheng Li et al. shows that PCR of synovial fluid leads to a sensitivity of 70%, which is comparable to synovial fluid cultures [

31]. However, standard cultures do have limitations compared to PCR. PCR is superior when it comes to identifying low-virulence microorganisms, PCR results are available faster compared to cultures and PCR is still accurate after previous antibiotic treatment [

32,

33]. The advantages of PCR become clear in the study by Ghirardelli et al. In this study, PCR was the main determinant for diagnosing PJI and identified the causative microorganism in 63% of patients, versus 26% with standard cultures [

33].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is an upcoming technology with the ability to identify microorganisms in synovial fluid. A meta-analysis of Hantouly et al. shows that NGS has an excellent sensitivity of 94%, which is a lot higher than the sensitivity of 70% for synovial fluid cultures. However, the specificity of NGS for diagnosing PJI was lower compared to cultures, 89% versus 94% [

34]. A high sensitivity is valuable in case of hard-to-detect low-virulent pathogens. This is clearly shown in the study by Hong et al. In this study, NGS identified potential causative microorganisms in 47/98 (48%) cases with a culture-negative PJI [

29]. In a smaller study with 11 cases with a culture negative PJI, NGS was able to identify a potential microorganism in up to 82% [

35]. An important limitation of NGS is the possibility of false positive results, since it is difficult to differentiate between contamination and infection. This leads to a lower specificity [

34,

36].

Molecular biologic tests can be incorporated into daily practice in a variety of ways. They could be implemented as a standard part of the analysis for PJI. However, as there are considerable costs related to the use of these tests, and the current diagnostic workflow already achieves acceptable diagnostic accuracy, this is considered an unnecessary expenditure. It may be more feasible to introduce molecular biologic tests in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, such as in the group of patients with an inconclusive aspiration or dry tap. In that case, it would be an option to include these tests in combination with the tissue cultures during biopsy. Finally, one could introduce the molecular biologic test as an additional diagnostic during revision surgery in the cases where uncertainty remains even after biopsy culture results. In this case, it would be needed in the least number of cases and therefore would introduce lower costs. Which of these different integrations in daily care is cost-efficient and provides the most benefit to the patient should be studied prospectively.

The limitations of this study are reflective of its retrospective design. In some cases, information was incomplete or unclearly written in medical records and, therefore, not all variables were available. Histological findings were available in few cases; therefore, these were not evaluated even though they are part of the EBJIS criteria. Our study lacks a direct comparison between synovial fluid aspiration cultures and biopsy cultures. We have not made the direct comparison, because we feel the most important incentive to consider performing biopsy is a dry tap aspiration. As in the case of dry tap there is no result to compare to the biopsy result, and for inconclusive results the decision to perform additional biopsy is subjective, we feel the retrospective design of our study may introduce bias in a direct comparison. Direct comparison of synovial fluid aspirations and tissue biopsy cultures could be the subject of a prospective evaluation. Finally, not in all cases was revision surgery performed. Thus, the final PJI diagnosis has not been confirmed with intraoperatively taken tissue cultures in all cases.

In this study, we did not perform a formal cost-effectiveness analysis of the diagnostic work-up. However, we can speculate on whether adding a biopsy after dry tap aspiration of the hip is cost-effective. The costs of biopsies are relatively low. They are performed in the OR under general anesthesia, but patients are admitted and discharged on the same day, and estimated costs are EUR 500–700 including the costs for the cultures. The costs for a two-stage revision are conservatively estimated at around EUR 30.000–50.000, the costs for aseptic (partial) revision at EUR 6000–8000 if complications are avoided. Therefore (in the worst-case scenario), the number needed to treat to be cost-effective would be around 31 biopsies ((30,000 − 8000)/700 = 31.35). Probably, the numbers are even more favorable.

Many studies on the value of synovial fluid aspiration, additional biopsy and peroperative tissue cultures solely focus on the measured sensitivity and specificity of these diagnostic procedures. A low sensitivity of tissue biopsy cultures can easily be misinterpreted as a reason not to perform a biopsy even when clinical suspicion of PJI is present. Our study evaluates the percentage of cases in which clinically relevant changes to the treatment strategy were caused by the tissue biopsy results. For further research, our findings need to be validated in a larger prospective study.