1. Introduction

Frailty is a clinical syndrome characterized by a reduction in an individual’s capacity to cope with stressors and is a result of cumulative impairments in multiple physiological systems [

1]. Polymedication typically refers to the concurrent use of five or more medications, although there is no consensus regarding this definition. The relationship between the two syndromes appears to be bidirectional [

2].

From the perspective of the frail patient, appropriate treatment of comorbidities enables the effective management of chronic health problems, improves quality of life, minimizes the level of dependence, and increases life expectancy. Nevertheless, the term ‘polymedication’ is not without a certain negative connotation, as it is associated with the unnecessary and/or off-label use of drugs. In light of these considerations, the purely numerical criterion for categorizing a patient as polymedicated may prove to be of limited utility. When frailty represents the primary concern, the use of multiple medications should not automatically be regarded as a cause for concern, provided that they are appropriate [

3].

Thus, managing medication appropriateness according to the clinical condition and desired clinical outcomes of a frail patient represents a pivotal aspect of his/her assessment. Additionally, when regularly monitoring frail adults, healthcare providers should consider deprescribing strategies to reduce the risk of adverse drug events and improve medication safety, and they should adjust medication regimens when needed. Moreover, the role of variables such as age and gender in any potential intervention must be considered given their well-documented correlation with frailty and the use of multiple medications.

A medication review (MR) is a systematic assessment of the medications taken by a patient to ensure safe and effective use and to achieve optimal health outcomes [

4]. The MR is a core component of the comprehensive geriatric assessment, as it enables the identification of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs). The lack of available evidence on the benefits of specific drugs in frail patients, together with the strong association between polymedication and frailty, makes deprescribing a very appropriate strategy [

5].

Many tools are employed in routine clinical practice for the screening of frailty and the assessment of medication appropriateness. Some are particularly well suited for use by a primary care physician and/or a community pharmacist operating in rural areas, as they facilitate rapid screening without the need for specific instrumentation. In the context of deprescription, particular emphasis is placed on medications that may contribute to an elevated risk of falls and/or have a high anticholinergic burden [

6]. The most widely used criteria for assessing PIMs worldwide are the Beers and the screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions (STOPP) criteria [

7,

8]. In the specific context of community pharmacy, tools such as pharmacotherapeutic follow-up and compliance aid systems, which are designed to identify drug-related problems and address the negative outcomes of medication (including non-adherence issues) [

9], are particularly well suited for the management of frail patients.

Primary care services (general practice and community pharmacy) act as the ‘front door’ to the health system. In rural areas, these professionals serve as the unique point of access to healthcare for each individual and maintain close and continuous contact with all patients. This practice setting offers an optimal environment for the MR, the identification of PIM, the acquisition of valuable information for deprescribing, and the development of coordinated strategies based on the results obtained.

The objective of this study is to assess the relationship between medication appropriateness and variables related to frailty in a rural population and to propose potential strategies for optimizing medication in frail patients through tailored multidisciplinary interventions.

3. Results

The majority (52%,

n = 241) of individuals registered within the municipality are patients over the age of 50 years with long-term medication regimens.

Table 1 provides an overview of the variables examined in relation to patient frailty. A total of 20.8% of the patients exhibited a score indicative of frailty. The prevalence rose to 40% when the age was limited to 65 and above. Age and gender were significantly associated with frailty, with the condition being more commonly observed among females, as well as in individuals aged 80 and above. The number of medications (NOM) was twofold higher among frail patients compared to their non-frail counterparts (10 vs. 5). The use of pharmaceutical agents with documented associations with falls and the anticholinergic load was also significantly associated with frailty.

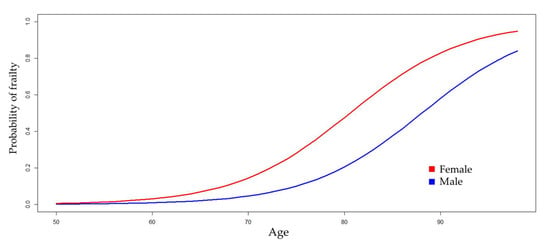

Table 2 shows four logistic regression models for estimating the probability of frailty. Model 1 was constructed by incorporating the non-modifiable variables (age and gender) of the patient. The results indicate that, in individuals of the same age, being female can increase the odds ratio (OR) of frailty by as much as nine times, with 95% confidence. Similarly, in individuals of the same gender, with each year of aging, the OR increases by 13% to 25% (

Figure 1).

Three multivariate logistic regression models were fitted, alternatively incorporating one modifiable variable into Model 1: Model 2 incorporates the NOM, Model 3 FRIDs, and Model 4 the CALS score. The ORs for gender and age show a notable degree of stability across all models. Model 4 suggests that the anticholinergic load has a greater impact on frailty than the NOM or FRIDs. For individuals of the same gender and age, each additional anticholinergic unit increases the OR by a factor of 1.2 to 2. An additional model was constructed using the five variables under investigation. In this model, the statistical significance of the NOM and FRIDs was lost, while the anticholinergic load maintained its significance.

Table 3 shows (i) a summary of the PIMs detected during the MRs performed for frail patients and (ii) the proposed intervention strategies designed and coordinated between the primary care physician and community pharmacist. Recommendations were classified as priority interventions (PIs) if their implementation was feasible within our context and with the resources at our disposal. Conversely, those that necessitated referral to other levels of care or specialized follow-up were designated as complex interventions (CIs).

Anticholinergic drugs were prescribed to 94% of the patients under review, with a mean CALS score of 3 (ranging from 1 to 10). The most potent agents were urinary antispasmodics, while the primary contributors to the overall load were found to be antidepressants. A total of 46 patients were taking at least one FRID, with an average of 2.3 ± 1.6 per patient, ranging from 1 to 7. Antidepressants and diuretics were the FRIDs most frequently identified as PIMs. An average of 2.1 ± 1.6 STOPP criteria (range 0–6) were fulfilled. Two patients did not fulfill any STOPP criteria. Treatment with anxiolytics for a period exceeding 4 weeks and the prolonged use (longer than 8 weeks) of peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux agents were the most frequently recorded.

4. Discussion

There is an intimate relationship between frailty and aging. This issue is of particular concern in rural environments, where the rates of aging and population decline are even more pronounced than in urban contexts. However, the prevalence of frailty in rural areas has been explored in a limited number of studies [

18]. Those conducted in Spain have reported a prevalence of frailty ranging from 8.4% to 20.4% [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The frailty and dependency in Albacete (FRADEA) study, which was conducted in our geographical area, reported a frailty prevalence of 65.4% among individuals over the age of 70 [

23]. Our data revealed a prevalence of 45.2% in this age group. The observed differences may be attributed, to some extent, to the distinctive characteristics of the populations (the FRADEA study included institutionalized patients). Further investigation is warranted to ascertain the influence of rurality on frailty and health outcomes.

All multivariate regression models revealed that the OR of developing frailty is heightened in females (see

Table 2). The relationship between the female sex and frailty prevalence has been a subject of long-standing recognition and is thus termed the ‘sex–frailty paradox’ [

24]. In addition, the incidence of frailty and prefrailty was also higher in women than in men [

25]. Moreover, given the holistic nature of frailty, it is plausible that psychosocial variables or behaviors exert an influence on the syndrome. Since personal and medical factors contributing to social vulnerability and frailty are related, women may be more socially vulnerable than men, which could, in turn, contribute to their higher frailty levels [

26]. It can be argued that PIM criteria and deprescribing tools that include gender as a factor in determining frailty may be lacking [

27].

Regular assessments of pharmacological treatments at crucial stages are essential to guarantee that frail individuals continue to receive secure and appropriate medications. The involvement of a primary care physician and a pharmacist in the MR process has been demonstrated to positively impact the implementation of recommendations [

28,

29]. Furthermore, bidirectional communication between healthcare professionals has been shown to reduce the prevalence of duplicate treatments, which represents the most frequently cited STOPP criterion [

30].

A substantial body of literature exists on the use of tools to detect PIMs in Spain or Europe [

31,

32]. The most frequently reported PIMs in community-dwelling patients were benzodiazepines, antiplatelet agents, proton pump inhibitors, and opioids. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted that utilize the most recent update of the STOPP criteria. However, our data largely align with the findings reported in the existing literature, and the appropriateness of medication use in our frail patient sample is satisfactory overall.

The aforementioned tools fail to account for individual patient information, including psychosocial or/and behavioral variables, which could prove relevant. A crucial element of deprescribing is the active involvement of patients, who must assume a primary role in the management of and compliance with their treatment plans. Recurrent face-to-face interactions inherently entail the acquisition of information regarding psychosocial and personal contexts. Given the prevailing structure of Spanish Healthcare Systems [

33], overcoming this limitation in rural settings seems more feasible than in urban contexts.

The assessment of frailty in rural primary care settings represents a significant challenge that necessitates a personalized approach. In this context, the STOPP criteria should be regarded as a preliminary screening tool, the results of which can be used to define an initial list of priorities. Using this approach facilitates deprescription in frail patients in real-world settings [

34]. Regardless of the existence of deprescription criteria, and since the process may be complex, the risk–benefit ratio of any given intervention should be thoroughly evaluated. In fact, clinical practice guidelines already include frailty as a therapeutic determinant [

27]. When reviewing the medication of a frail patient, it is essential to keep all of this in mind. A collaborative analysis of the collected data allows for the development of tailored interventions that should be discussed from the perspective of frailty.

Four out of five frail patients were treated with an anti-peptic-ulcer agent. The rationale for this is that proton pump inhibitors are indicated as prophylactics in prolonged treatments with acetylsalicylic acid in Spain [

35]. A review of the medical record and an assessment of the necessity for an antiplatelet agent are proposed to be the primary focus of the intervention. If needed, gradual withdrawal is advised to avoid rebound acid hypersecretion.

Metformin is the treatment of choice for the management of diabetes mellitus in frail patients [

36]. Despite its anticholinergic activity, treatments with metformin are considered appropriate, except in cases of chronic kidney disease (stage 4).

The inappropriate use of acetyl-salicylic acid in the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases can be easily assessed. Moreover, deprescription of the antiplatelet agent eliminates the need for gastroprotection. A more detailed analysis is required for treatments with anticoagulants. It is advisable that patients undergoing concurrent treatment with both direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and glycoprotein P inhibitors be monitored regularly for bleeding risk assessment. As far as anti-vitamin K appropriateness is concerned, switching to DOAC therapy in frail patients has been associated with an increased risk of bleeding without a reduction in thromboembolic events [

37]. Thus, any change should be carefully considered.

Furosemide is used in conjunction with other drugs to manage hypertension. When modifying a furosemide-based treatment plan, several factors must be considered, including the presence of kidney disease, edema, inadequate blood pressure control, or other comorbidities. In most cases, a gradual dose adjustment may prove more appropriate than treatment withdrawal [

38].

The decision to utilize statin therapy in frail patients is contingent upon their functional status and age. In patients under 75 years of age, treatment is recommended in accordance with the level of cardiovascular risk. For patients over 75, a comprehensive geriatric assessment is recommended, given that their functional status exerts as much influence as traditional cardiovascular factors on the risk of mortality [

39]. Statins for primary cardiovascular prevention in persons aged 85 and over with established frailty is a STOPP criterion [

8].

The use of chronic opioids may increase the risk of prolonged sedation or confusion. Additionally, due to their ACB, they may increase the risk of falls and subsequent fractures [

40]. It is preferable to reduce the dosage using pharmacological alternatives without anticholinergic activity.

Benzodiazepines and their analogs are clear candidates for deprescription in frail patients. This is a complex and time-consuming process that is particularly challenging to implement in a primary care setting, thus necessitating a referral. Several programs involving different professionals have been proposed for deprescription, and they have shown that a gradual reduction in the drug dosage may be an effective strategy. Furthermore, it is crucial to coordinate and agree on decisions with the patient throughout the process. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a useful element in this process [

41].

Among the frail patients assessed, approximately 60% were treated with antidepressants. Frailty and depression share symptomatology and risk factors. Moreover, frail patients may not respond to antidepressant medication as well as their non-frail counterparts [

42]. Primary care professionals can easily assess the control of the pathology through validated tests [

43]. Further interventions require a specialist physician referral.

Urinary antispasmodics are the drugs with the greatest anticholinergic load. Depending on the degree of symptom control, dose tapering or deprescription can be attempted. Mirabegron may be a non-anticholinergic alternative treatment option. Non-pharmacological treatments represent an additional effective therapy, although they necessitate the involvement of qualified professionals [

44,

45].

Some limitations must be mentioned: (i) This study was conducted in a single municipality. This, in turn, enables an exhaustive examination of the population and facilitates the tailoring of effective interventions. While we do not intend to generalize, a multicenter study may yield more valuable insights. (ii) The design is cross-sectional, which precludes the possibility of establishing a causal relationship between the appropriateness of the medication and any variable or documented health outcome. This goal falls within the scope of a broader, more ambitious investigation. Given the complexity of the task at hand and the necessity of interdisciplinary collaboration, we believe that it is not viable to pursue this undertaking as a standalone investigation.