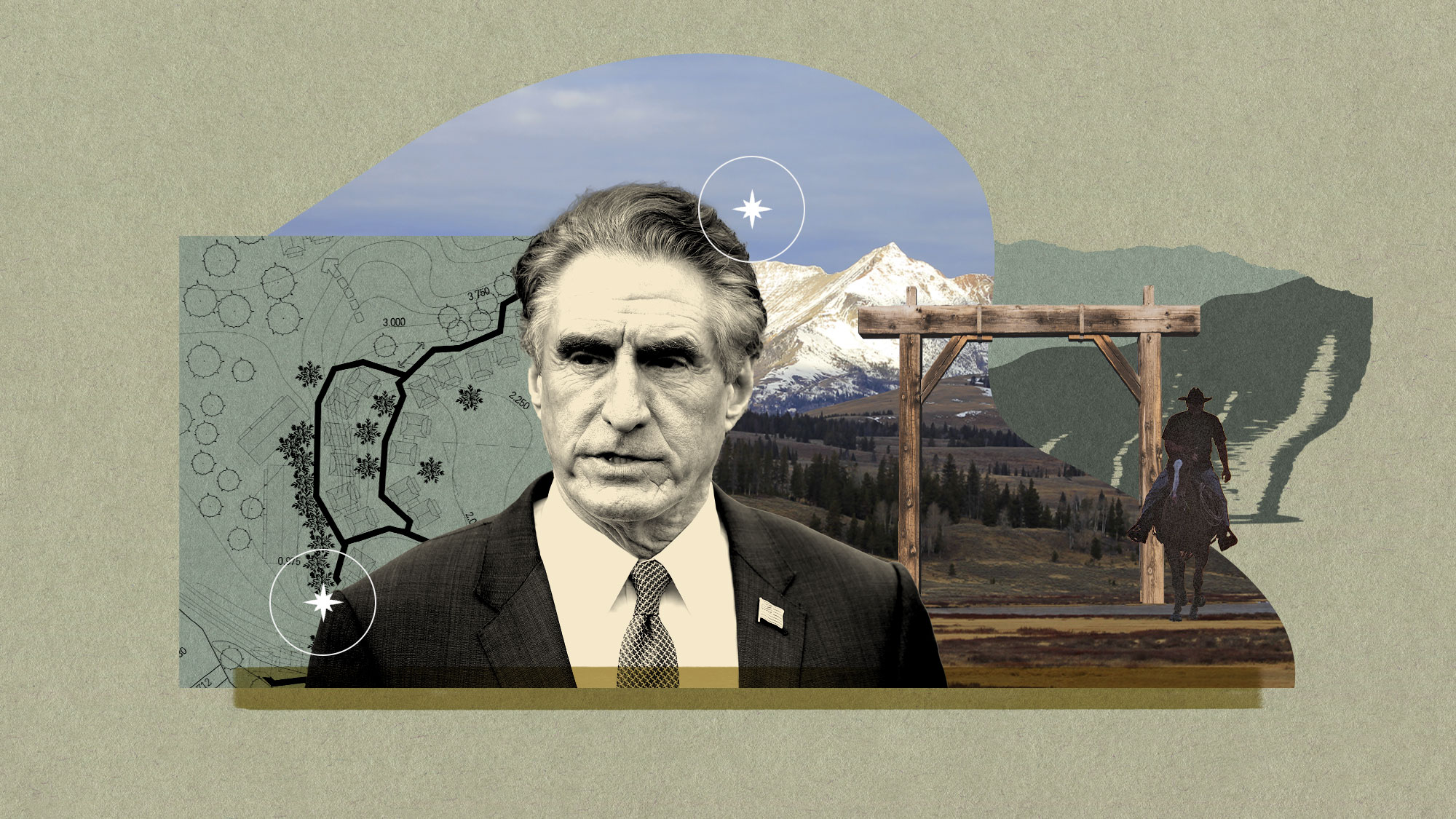

The Trump administration is poised to begin offloading public land, achieving a long-held conservative goal of reducing the government’s footprint in the West. Federal agencies manage around 640 million acres, or about 28 percent of the nation’s land, an invaluable resource Interior Secretary Doug Burgum has called “America’s balance sheet.” His membership in a luxury real estate club in Montana provides an apt example of how private interests stand to profit from federal lands.

Last month, the Interior Department and the Department of Housing and Urban Development announced a plan to make large tracts of government land available to developers. “As we enter the Golden Age promised by President Trump,” Burgum wrote on March 17, “this partnership will change how we use public resources.”

Little has been shared so far about the process for identifying parcels or how they might be sold or transferred. Burgum told CNBC the Interior Department would consider selling hundreds of thousands of federally-managed acres within 3 miles of urban areas. Jon Raby, the acting director of the Bureau of Land Management, told Bloomberg News the initiative would consider land within 10 miles of towns of 5,000 people. “Either they are making this up as they go along, or the right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing,” said Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities, a nonpartisan conservation group.

The task force said it will deliver a report to the National Economic Council by today, identifying parcels and outlining how much housing would be built. It also will offer recommendations to “reduce the red tape behind land transfers or leases” by “[s]treamlining the regulatory process.” The Interior Department declined an interview but said in a statement to Grist that “all options are being explored.”

Burgum’s connection to the Yellowstone Club demonstrates the potential conflicts of interest that can arise with federal land transfers. According to documents filed with the U.S. Office of Government Ethics, which declined to comment, Burgum has not divested his financial interest in the Yellowstone Club. The luxury real estate investment firm owns an exclusive community that covers about 14,000 acres and includes a members-only ski resort. Burgum owns two homes and additional financial interests in the development, which is about an hour south of Bozeman, Montana.

Over the last 30 years, the Yellowstone Club has used public land transfers and sales to amass holdings that include a private mountain, trophy trout waters, and an exclusive resort that caters to the wealthy and powerful. Its most recent deal saw the company, which declared bankruptcy in 2009 and was acquired by private equity firm CrossHarbor Capital for a fraction of its value, embark on a controversial land swap in southwestern Montana.

That deal was finalized January 17, during the last days of the Biden administration and two months after President Trump nominated Burgum to lead the Interior Department. The Yellowstone Club received 3,855 acres from the U.S. Forest Service in the readily accessible foothills of the Crazy Mountains. In exchange, it gave the Forest Service, which is part of the Department of Agriculture, 6,110 acres of land with fewer recreational opportunities and less valuable wildlife habitat high in the Crazies and the Madison Range. The value of the exchange, which critics argued dramatically reduced access to the mountains by eliminating access to established trails, was never disclosed.

“The version they approved was purposely meant to make it harder for the public to access what remains,” said Nick Gevock, a campaign organizer for the Sierra Club. “By strategically trading lands you can restrict access to thousands of acres of public land, and effectively make them private.”

William Campbell / Corbis via Getty Images

A representative of the Yellowstone Club said in a statement that Burgum “has nothing to do with Yellowstone Club development nor does he have anything to do with the land exchange.” The statement also said that “the Yellowstone Club is one of numerous private landowners involved in the exchange in two mountain ranges,” and noted the Club saw a net reduction in its land holdings with the deal. It also said the swap included conservation easements to protect land on Crazy Peak and in the Madison Range, and that the Forest Service received several tracts it had long sought. The Forest Service declined to comment.

Opponents, including conservative hunting and angling groups, claimed the process violated environmental regulations and misled the public about the Yellowstone Club’s involvement as a neutral party when it paid the bulk of the transaction costs. Gevock, who started following the Club’s business dealings 24 years ago as a reporter for the Bozeman Chronicle, said more than 80 percent of public comments submitted to the Forest Service opposed the deal. That land, which was popular with skiers, hunters, anglers, and hikers, is now beyond the public’s grasp.

“Once the title is transferred, you never get it back,” he said.

The Yellowstone Club — which, through its subsidiary development manager Lone Mountain Land Company, is the de-facto governing structure for the town of Big Sky, Montana — sits close to a great deal of prime federal real estate, including parcels managed by the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the Forest Service. Critics fear that land may now become available to industry and developers.

Richard Painter, who served as the chief ethics lawyer to President George W. Bush from 2005 to 2007, told Grist there are several ways that any acquisition of federal land by the Yellowstone Club could affect Burgum’s financial interests, including changing the value of his properties or potentially lowering fees that the club’s homeowners pay. If the joint task force sets legal precedent to streamline or reduce regulations around federal land swaps, that could impact the Yellowstone Club’s future dealings. If Burgum helps facilitate or speed up future land swaps between the Department of Interior and the club, it would be a direct ethics violation. As a result, “I would strongly urge that he recuse himself from any land swap regulations,” Painter said.

Painter told Grist the Interior Department has been a “problem child in ethics” for years, and he testified to Congress about it last April. He warned about the longstanding close ties between senior Interior Department officials and private industry, and the growing influence of corporations. Congress and the Interior, he said, have a “fiduciary obligation to oversee the administration of federal land for the American people, not just for whoever wants to go and get preferential access to land.”

Burgum has used the Yellowstone Club in his political role, hosting a fundraiser with Trump last August there that donors paid $100,000 to attend. He also is not the only politician with ties to the club. Energy Secretary Chris Wright is a member, as are Montana Governor Greg Gianforte, U.S. Representative Troy Downing, and U.S. Senator Tim Sheehy. “This is the billionaire class wanting to run the country,” Gevock said, “and their vision for the Rocky Mountain West is privatization.”

In its March announcement, the Interior Department positioned its joint task force on selling public land as a chance “to build affordable housing stock.” But experts question whether anything that comes of this plan would be accessible to low-income families or actually lower housing prices.

Supply constraints are not the primary factor for the country’s housing crisis. Housing stock has risen steadily since 1980, according to a 2023 Congressional Research Service report, although not always where it’s most needed or at the right prices. “On a national level, it is not necessarily obvious that there is a shortage of housing units,” the report found.

“We actually have more of a supply mismatch than a supply problem,” said Karen Chapple, director of the School of Cities at the University of Toronto. A generation of empty nesters is deciding to stay put rather than move into smaller homes, reducing the national supply of single-family homes in urban areas, she said, even as rural communities see vacancies created by people moving in search of opportunities. And high mortgage rates have recently led people to stay put, reducing the overall supply of homes for sale.

Much of the acreage the government manages is in the West and Alaska, often far from jobs and essential infrastructure like roads, water, sewer, and schools. “Everyone who can’t afford housing in Massachusetts is not just going to move to the middle of nowhere in Idaho,” said Brett Hartl, government affairs director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

Instead, the proposal reflects a history of Republican attempts to dismantle public lands that dates to the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s, when conservatives opposed to federal regulations argued states could better manage Western land. (President Reagan named one of the movement’s allies, James Watt, as Secretary of the Interior in 1981.) The idea still enjoys support among developers, ranchers, and others interested in profiting from the land.

The general public largely opposes the idea. A recent Colorado College poll of Western voters found 82 percent disapproved of selling federal land to address the region’s housing problems. “The land seizure movement is wildly unpopular across party lines,” Weiss said. “You’re getting to the point where the polling is as obvious as asking if people like apple pie.”

On top of widespread opposition, basic math has gotten in the way. The federal government often operates public lands at a loss: The Bureau of Land Management, for instance, regularly spends 10 times as much managing grazing lands as it collects in fees. If states took over, they would bear the cost of essential services like wildfire management. That is noteworthy, Weiss said, because the areas under consideration lie in “the wildland-urban interface, the most dangerous place to build.”

That hasn’t kept the idea from resurfacing. During Trump’s first term, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke held a closed-door meeting to discuss transfers with the American Legislative Exchange Council, a conservative think tank that favors giving states control of federal land. Zinke opposed the notion, but still oversaw the largest giveaway of the modern era. (One of the scandals that eventually led to his resignation involved a real estate deal with the chairman of oil services company Halliburton while it benefited from unprecedented federal leases.)

Utah Republican Senator Mike Lee has emerged as a leading advocate for reducing federal land ownership. In 2022 and again in 2023, he introduced legislation authorizing the sale of government land to developers. He also supported a lawsuit seeking state control of 18.5 million acres held by the Bureau of Land Management; the Supreme Court declined to hear the case in January.

Meanwhile, Project 2025, the conservative blueprint for Trump’s second term, laid the groundwork for the latest push. The chapter on the Interior Department was written by William Pendley, who led the Bureau of Land Management during Trump’s first term and once argued that the “Founding Fathers intended all lands owned by the federal government to be sold.” It calls the government “a bad manager of the public trust” and proposes sweeping changes, including weakening environmental protections and increasing drilling, mining, and logging on public land.

Kathleen Sgamma, who was Trump’s pick to lead the bureau until she withdrew from consideration last week, also contributed to the chapter. The oil and gas lobbyist previously signaled her support to offload the country’s land. When a dispute over federal grazing fees prompted a standoff between ranchers and the bureau in Oregon, she said the incident “arises from too much federal ownership of land in the West.”

In the meantime, Katharine MacGregor, vice president of fossil fuel-focused NextEra Energy, was confirmed as a deputy interior secretary in April. During her nomination hearing, MacGregor promised support for over a decade of oil and gas leases. (Watchdog group Fieldnotes found she had systematically concealed public records during her previous time at the Interior, concealing information about her extensive interactions with oil and gas executives.) Burgum also told oil and gas executives in March that selling public land could eliminate the $35 trillion (and growing) national debt.

Even as Burgum positions such deals as a solution to the nation’s woes, critics warn that the lack of safeguards could lead to unintended consequences. There is nothing to suggest the joint task force or the Trump administration will take steps to “prevent those [housing developments] from just turning into vacation homes for billionaires,” Weiss said. And many of the federal employees who would oversee the venture have recently been fired. The Trump administration intends to cut Housing and Urban Development by 84 percent, and has frozen $60 million in funding for other affordable housing developments, stalling hundreds of projects.

“At every level, it’s a scam and a con,” Hartl said, “and the only people that will benefit from it are the people that already benefit from the housing crisis.”

Source link

Lois Parshley grist.org