1.1. Circular Path in Floor Plans

“Floor plans often reflect the interpretation of a certain notion of living, which can be expressed in the internal organization, in the opening and closing of rooms, in the connection and grouping of rooms, in the connection or isolation of functions, and, last but not least, in paths and sightlines” [

13]. The latter two aspects are of great importance in the context of floor plans with circular paths, which emphasize the connection between spaces and optimize internal routing. According to the ‘Floor plan manual’ [

13], the implementation of these principles creates the most functional and spatial relationships between different spaces, where each room can be reached via two or more paths. The multitude of possible paths allows the user to experience the house from ever new perspectives and makes it appear more diverse than it actually is.

The importance of interconnecting rooms is also explicitly mentioned in Alexander’s Pattern language [

2] in the pattern ‘The flow through rooms’. There, it is emphasized that “the movement between rooms is as important as the rooms themselves”, which has a great influence on social interaction in the rooms. It is also said that generous circulation allows everyone’s instinct and intuition full play, while ungenerous circulation inhibits it. The circulation path is called a loop, which runs through all the important spaces and gives the feeling of generosity or spaciousness. In such a loop, it is always possible to walk in different directions or continuously move in ‘circles’. This provides the generosity of movement that connects the rooms [

2] and consequently affects social relationships [

14].

In order to create meaningful connections between rooms, it is important to understand that movement within the housing unit/apartment has different purposes [

15]. These include the following:

Functional aspects (daily tasks such as cleaning the apartment, access to people in the rooms, closing windows due to drafts…);

Safety aspects (evacuation in case of fire or other threat, visual control of the space…);

Comfort aspects (such as relaxed and unhindered movement, dancing, children playing, walking around the apartment, thinking while walking, walking dogs…).

Movement can be associated with absolutely necessary activities (such as access to the kitchen to cook), but also with optional activities (such as a walk around the apartment)—here, the parallel is drawn with Gehl’s study ‘People on foot’ [

16]. The type of movement in a particular house/apartment depends on the configuration of the floor plan. In this respect, the different floor plan typologies that have evolved over time are based on different concepts of spatial organization that also reflect different cultural dimensions and the complexity of human habitation [

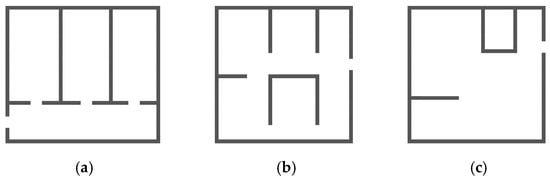

12]. For example, if we look at three basic contemporary floor plan typologies, such as a corridor/hall floor plan, a floor plan with a circular path, or a continuous floor plan, they show different types of access between rooms and allow different ways of moving around the space (

Figure 1). The difference lies in the way the rooms are connected to each other. In the corridor type, each room is accessed from the corridor, which serves as a central communication point. In this case, the rooms are independently accessible and completely enclosed [

13]. In comparison, with a continuous floor plan, the room boundaries are reduced to a few walls, and the individual rooms always relate to the entire space, which allows for greater spatial dynamics (the case of lofts). A floor plan with a circular path lies to a certain extent between these two extremes as it creates a more spatial connection between the rooms than the corridor type, but, at the same time, it can also maintain the room’s function as an enclosed space (by simply closing the door).

Floor plans with circular paths as a typology are special in that, at least in parts of the house or apartment, even if not entirely, circular movement can be created as a continuous flow. In practice, the spatial composition of individual rooms and the position of the openings are such that circular movements between rooms, around rooms, or around other architectural elements, such as walls, cupboards, and other furniture elements within the housing unit, are possible [

17]. Characteristic examples of a circular floor plan design are houses or apartments with a central core (

Figure 2a), usually containing service areas such as a kitchen, bathroom, storage room, or even a staircase condensed into the central core, so that the remaining living space allows circular movement around the core while providing longer sightlines and the perception of an enlarged dwelling [

18]. Another way to construct a circular floor plan is to arrange the rooms in such a way that they have more openings than are necessary for access (

Figure 2b). This gives us more possibilities to choose the way to the room and also the direction of access. The extent to which we set up circular movement depends on the needs and possibilities, the size of the home, the question of privacy, and, last but not least, the personal preferences of the users. If the passage is defined by a door, it can also be selectively opened, closed, or locked so that the passageway can be regulated over time according to the specific needs of the users [

13,

19] (for example, a cupboard can be placed in front of the door when the passage is not in use, or they can be temporarily hidden). If you install more than one door/opening in a room, the question of their positioning arises—where should they be placed so that they do not interfere with each other? In architectural practice, we find that they are often placed axially—in several consecutive rooms [

20]. Another approach is to place doors/openings as far away from the existing door as possible, depending on the spatial possibilities. Examples of circular designs also show the placement of secondary doors/openings close to or next to the outer walls of the building [

21]; above all, the actual position should always be contextual.

The concept of circularity can also be applied to other floor plan typologies, e.g., in the case of a renovation where a floor plan could be adapted with a different circular communication scheme. Circularity can also be created in larger rooms by placing furniture and appliances in such a way that circulation around them is possible.

In terms of social impact, this typology creates more opportunities for interaction between users (between residents themselves and/or between visitors and residents), which can be seen as a good thing if it is desired; otherwise, it can also lead to conflict. How integrated (accessible) or segregated individual spaces within the home should be often depends on specific cultural backgrounds and social circumstances/norms and should be left to the user. However, integration is seen as the key through which we can understand the social context of architecture and show how buildings and places function on a collective level. This applies to both buildings and individual spaces within a building [

12]. Furthermore, according to Hanson [

12], space organized for social purposes should be seen neither as purely continuous nor as purely bounded but as a transformation of the spatial continuum through a system of boundaries and permeabilities into an effective space organized for human purposes. This statement was based on an investigation within the framework of the ‘Social logic of space’ [

14], in which elementary buildings were defined as closed or open cells (the open segment of space can be traversed, while the closed cell is considered a dead end) (

Figure 3).

A similar concept is also explained by Jay Appleton’s Prospect refugee theory, also known as Habitat theory. This states that human environmental preferences are attuned to the search for spaces that provide a balance between prospect and enclosure [

22]. Although the work focuses primarily on outdoor spaces, it has also been extended to indoor spaces. An example of this is Hildebrand’s analysis of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture, in which he argues that the experience of moving through an environment is crucial to shaping a person’s emotional state [

23]. If the path one follows has the right balance between vista and enclosure, then the experience is psychologically calming or uplifting. This also emphasizes the fundamental connection between the path of movement and the visual dimension.

The general significance and presence of the typology discussed here can be seen from the fact that its origins can already be found in the organization of dwellings in the early history of human settlements. Simple building structures made it possible to move around the fire in the center of the room (for example, the Neolithic village of Skara Brae—

Figure 4a). Circular paths were often inherent to the building form and can be found as an architectural archetype in vernacular architecture all over the world. The internal organization of nomadic yurts [

12] allowed for circular movement around the central heart (

Figure 4b). Roman atrium houses had an atrium in the center (

Figure 4c), around which rooms were arranged (as in the House of the Faun). The circular movement in these houses focused on the atrium and formed a symbolic and functional center. Traditional Japanese houses were often organized around the atrium or main tearoom and connected by sliding doors that allowed flexible movement through the rooms. Renaissance villas were often planned to consist of interconnected rooms (

Figure 4d) that allowed circulation (as in the case of the Villa Farnese). An enfilade, a series of formally aligned rooms, was common in the 18th and 19th centuries in palaces but also in public buildings and allowed next to movement also long sightlines through successive rooms [

24]. This way of connecting rooms can still be found on a large scale in middle-class houses and apartment buildings at the beginning of the 20th century in Europe, until individualization (separate rooms with individual access) and specialization according to function began to be reflected more strongly in the design of floor plans [

20]. Nevertheless, many influential residential buildings were planned according to this principle in modern times (Casa Batllo, Villa Savoye, Steinhaus,…) [

24]. This also includes experimental houses such as the modernist Bailey house CSH N21 [

25]. On the other hand, the principles were also applied in floor plans of single-family houses with a more open and unconventional design as well as in multi-story apartment buildings [

21] and even in small units of social housing (such as ‘Roške stolpnice’ residential towers) [

18]. These and other examples show that this typology has been implemented not only throughout the history of human settlement but also in different scales and design variations.

Research on floor plans with circular paths is relatively modestly represented in the academic literature, although research on the quality criteria for floor plans in general is much stronger in residential architecture [

26,

27,

28], including the topic of circulation as a concept of movement. Basic circulation diagrams depicting human movement on architectural plans were already used as a method by Viollet-le-Duc in the second half of the 19th century, followed by Kerr and others [

20,

29]. In the paper Intimate circulation, Emmons describes how the flow diagram method used by architects was instrumental in envisioning what became a system of movement, which was isolated from the inhabited space but established schematic order of the house [

20].

Circulation paths were often represented using a graph structure and a visualization based on abstract ‘graph theory’. Such an approach has been implemented in many applications and was primarily based on the ‘space syntax’ approach—e.g., in the study of Palladian villas [

19]. The space syntax theory of Bill Hillier et al. is still of great relevance today in understanding the impact of spatial configurations on the facilitation of social encounters [

14,

30,

31]. Two of the most common techniques are ‘convex spatial analysis’, which provides a specific insight into the spatial and social properties of rooms in a plan, and ‘visibility graphs’, which are used to explore spatio-visual properties of locations in a plan [

19]. In the study on the space syntax of Bafna, an application for analyzing the relationships between spatial units within houses was discussed [

30].

The spatial analysis method was also used in the study by Natapov et al., who investigated how the typology of building circulation is related to human orientation [

7]. The article introduces three types of building circulation types and tests them on a complex building floor plan. Another article on building circulation investigates how building circulation can be optimized using the Indoor Walkability Index within BIM (as a parallel to the Walkability Index for pedestrians) by measuring factors such as distance, simplicity, and accessibility to solve complex circulation problems and support decision making in planning, particularly in building remodeling [

6]. The methodology uses computational data derived from the given BIM models. In a study on the preferences of floor plans of medium-sized apartments in China, the authors looked for quantitative parameters reflecting the spatial relationships between different apartments, including the measurement of walking distances between individual spaces of the apartment. The study also included view-related aspects in the comfort assessment, such as the notion of sight interruption; the actual distances between north and south windows were measured in relation to ventilation. In addition, a questionnaire survey was carried out in which respondents were asked to choose between different floor plans according to their own preferences [

13]. An early example of studies on the distances a housewife has to cover unnecessarily due to functional relationships in the kitchen was published in 1913 by Frederick in the book on rational housekeeping entitled ‘Efficiency studies in home management’. It served as the basis for the development of compact floor plans, not only for the kitchen but also for entire houses and apartments [

11,

32].

There is also a spectrum of research that covers technologically advanced approaches, such as computational and mathematical analysis of the spatio-visual properties of paths through houses using the so-called ‘isovist method’ [

23], as in the analysis of Frank Loyd Wright’s houses. Another study on circulation paths via virtual environments and simulations is based on accurate 3D models of the environments (e.g., through 3D point clouds) [

33]. Spatial navigation in immersive virtual environments can also be explored using an agent-based approach in a BIM environment or as a gamification process [

34]. Another study targeted the particular problem of path planning for 3D indoor spaces, relying on the so-called IFC (Industry Foundation Class) building models, which present an upgrade to BIM technology [

35]. A methodology has even been developed that translates sketched, data-driven spatial requirements into 3D building components within BIM to improve stakeholder spatial understanding and enable an analysis of building performance, etc., during the initial design stages [

36]. Communication paths are not only important to navigate people in indoor spaces but might also gain importance for delivery robots or domestic help robots, for example. This has been studied in research on planning the path of a mobile robot that needs to transport and deliver small packages within a multi-story building. A navigation tree was used to plan the route of a mobile robot and estimate the total length of a delivery route (including nodes, segments, and trajectories) [

37].

Generative design methods are also gaining ground. They are able to generate a large number of potential solutions for architectural floor plans [

38], as in a study in which the automated layout planning of over 2500 different apartment designs was used to evaluate the flexibility of a structural scheme [

39]; however, none of them appear to have been designed according to the principle of a circular floor plan. Ko et al. describe advances in graph-based approaches, e.g., with graph neural networks (GNNs), which allow models to be trained on data sets organized in the form of graphs and quickly generate very realistic floor plans, improving efficiency in generating a large number of floor plan variants [

40]. Advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning offer the opportunity to advance architectural spatial layout planning and avoid constraints and an iterative and labor-intensive process. Computer-aided support in the form of automated layout planning is already paving the way to create new perspectives and methods for user-centered design [

40,

41].

In this context, and despite technological progress, a better understanding of the quality criteria of architectural spatial layout planning, as well as human needs and society is required, if we are to follow Alexander’s thought that buildings only feel right for the people in them when the physical spaces (defined by columns, walls, and ceilings) are congruent with the social space (defined by activities and human groups), as defined in the pattern ‘Structure follows social spaces’ [

2].

In order to better understand the typology presented, we show some potential advantages and also disadvantages. The potential advantages of floor plans with circular paths are as follows:

Improved flow of movement (multiple entrances to rooms allow for a circular flow that creates a seamless connection between rooms);

Multifunctionality of spaces (spaces are often multifunctional, blurring the boundaries between circulation and living areas; corridors lose their exclusive function of providing access to spaces and become part of a larger, connected area) [

2];

Versatility and spatial quality (circular paths improve versatility, spatial quality, and visual impact; extending views as seen in the enfilade concept improves spatial perception and esthetic quality);

Perceived spaciousness (circular movement patterns can improve the perception of spaciousness in small apartments against a backdrop of rising house prices);

Flexibility in redesigning floor plans (interconnected spaces can provide greater flexibility in redesigning apartment floor plans);

Design reinterpretations (modern reinterpretations of traditional or unattractive floor plans).

Possible disadvantages of floor plans with a circular path are as follows:

Reduction in usable space (additional doors and openings can reduce the available wall space for furniture placement) [

13];

Impact on privacy (creating passageways between rooms can undermine privacy) [

20];

Security concerns (numerous openings and connections can raise security concerns as they can affect the clarity and control of the space);

Potential orientation issues (circular floor plans can sometimes compromise clarity and ease of orientation, especially in larger homes);

Technical challenges (air conditioning, ventilation, and other technical systems may require more complex solutions to enable an open, connected design);

Personal preferences (circular layouts may not suit everyone’s preferences or lifestyle, as some people prefer more compartmentalized spaces) [

20].

1.2. Aims of This Study

The design of spatial configuration, i.e., the search for a satisfactory arrangement of functional elements considering certain objectives and constraints, is required at almost every scale of architectural practice. This task is complex, considers multiple criteria, and is often poorly defined [

7]. In this context and despite the technological advances already mentioned, there is still no available method to measure the benefits of floor plans with circular paths while incorporating the measurement of visual aspects defined mainly by the length and number of views, simultaneously introducing the concept of single, multiple, and wide views.

This study addresses the theme of floor plans that allow circular movement between spaces with a corresponding visual impact within the housing units and defines the parameters for their evaluation, which directly affect the quality of housing.

When a user/investor decides to renovate a house or apartment, they not only want to use new materials and finishes, but they also often want to renew the floor plan itself to provide better access and connections, more light, more alternative movement options, and better views. These user requirements can also be fulfilled by incorporating circular movement into the floor plan.

Circular movement can be established in a floor plan by inserting new doors, larger openings in the partition walls between rooms, or even knocking down a wall between two rooms. The number of newly inserted doors and their location in the floor plan of a house or apartment that we want to renovate is generally different, so it is usually always necessary to design several variants of adapted floor plans. Choosing the best variant for implementation is not always easy, especially if there are many different rooms in the floor plan. When choosing, the architect/designer is most often helped by his experience, as well as intuition.

In order to select the most favorable variant design (with circular movement) in a less ‘random‘ but more systematic/rigorous way, here, it is proposed to select between variants with the help of an explicit methodological and mathematical approach. For this purpose, a new method, the so-called QLCM method (quality level of circular movement), has been developed, which allows us to calculate the quality level of the adapted floor plan variant with respect to circular movement.

The QLCM method can be used as a design tool to determine the best floor plan variant in terms of both circular movement and visibility, which offers shorter accesses, better connections between rooms, longer walking in a loop if desired, and better communications, as well as additional longer and wider views, giving the feeling of a richer and larger space, satisfaction, and generosity. In this way, the application of the proposed QLCM method leads to a better life for the occupants/users who decide/agree to implement circular movement in the floor plan during the renovation as it addresses the design gaps and possible solutions.

The method is tested on three case studies of the conversion of three typologically different apartments/houses from non-circular to circular layouts, which are presented at the end of this paper.