1. Introduction

Wound healing and regeneration are important physiological processes for the survival of animals against accidental mechanical damage to the body in most animal phyla, including Arthropoda [1,2,3]. In insects, the outermost barrier is cuticular exoskeletons, which are lined with epidermal (epithelial) cells [4]. When these integumentary cuticles and cells are physically damaged, insects can repair wounds and often regenerate lost body parts. To achieve wound repair, insects must restore cuticular structures with sufficient mechanical rigidity via targeted cuticle deposition [5,6]. In the research field of wound healing and regeneration, Drosophila larval imaginal disc regeneration and embryonic dorsal closure during development have been studied as model systems to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms of wound healing and regeneration, which may be applicable not only to invertebrates but also to vertebrates [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

In Drosophila systems, actin networks play important roles in the process of wound healing [14]. Actomyosin filaments assemble at the wound edge, which is called actomyosin flow, during cytoskeletal remodeling [15], and the contraction of an actin purse string closes the wound [10,16,17]. Actomyosin remodeling requires polarized E-cadherin endocytosis [18]. Calcium signals play an important role in these processes [15]. For example, annexins are rapidly recruited to the wound edge in response to calcium signals, leading to the formation of actomyosin filaments [19]. Indeed, calcium signals are likely to be master regulators of the wound-healing process in Drosophila pupal wing tissues [20]. In response to mechanical damage, slow, long-range intercellular calcium waves occur, which are mediated by the IP3 receptor (and hence via IP3), a calcium pump called SERCA (sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase), and gap junctions in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc [21,22]. In other words, calcium and/or IP3 travel intercellularly through the gap junctions. According to a mathematical simulation study, intercellular transfer of IP3 is required for long-range calcium signals around the wound [23]. During wound healing, mitochondrial fusion and/or fission may regulate calcium signals in Drosophila [24]. An important additional point is that mechanical forces should be provided to repair wounds physically [25]. In the Drosophila wing imaginal disc, spatiotemporal patterns of intercellular calcium signals appear to reflect cell shape anisotropy and may convey mechanical information to cells [26]. Calcium signals activate NADPH oxidase DUOX (a dual NADPH oxidase) for the production of hydrogen peroxide, which may act as an attractant for immune cells [27].

Wound healing may recapitulate the normal process of morphogenesis and vice versa; in this sense, Drosophila dorsal closure has been studied intensively [28]. Importantly, dorsal closure in Drosophila requires not only cell migration but also mechanical forces from purse string structures and other sources [29,30]. There is no doubt that mechanical forces are crucial for realizing morphogenesis and wound healing because they are mechanical processes involved in cellular activities [31]. To be sure, many molecules are involved in wound healing [32,33] and dorsal closure [34], including extracellular matrix molecules [35]. Many molecules, such as cytokines, are involved in the recruitment of hemocytes in Drosophila [36]. Mechanical forces and cellular and molecular dynamics should be coordinated, as modeled in Drosophila dorsal closure [37].

In concert with these signaling and remodeling activities of the epidermis, physical damage causes innate immune responses [38,39,40]. In Drosophila, most hemocytes are plasmatocytes, which have professional phagocytic functions similar to those of mammalian macrophages to remove cellular debris in concert with other processes of wound healing and regeneration [4,38,39,40]. In Drosophila, another type of hemocyte, crystal cells, are involved in melaninization via phenoloxidase, which is a part of the innate immune system [4,38,39,40,41]. Melanogenesis via phenoloxidase plays various roles in insect physiology, including wound healing, sclerotization, coloration, and immunity [42,43]. Similarly, DOPA decarboxylase, which produces dopamine and serotonin, plays various roles in insect physiology, including wound healing, sclerotization, coloration, and immunity [44]. In one of the lepidopteran species, the cabbage white butterfly Pieris rapae, three types of hemocytes, namely, prohemocytes, plasmatocytes, and granulocytes, have been reported to constitute the major hemocytes [45,46].

In the pupal wing epidermal (epithelial) tissues of butterflies, puncture damage is repaired quickly, and repaired adult wings can be observed after eclosion [47]. Intriguingly, repaired damage sites often accompany eyespot-like ectopic color patterns [47,48,49,50,51]. Calcium oscillations and propagating waves are induced at the damage site but are also observed spontaneously from the prospective eyespot focus (i.e., the eyespot organizer) [52]. Moreover, the prospective eyespot focus expresses many kinds of genes involved in wound healing and calcium signaling [53]. Hence, it is understandable that normal color pattern formation during development and ectopic color pattern formation after wound healing are mechanistically similar in butterflies. Ectopic color patterns and calcium signals are induced by puncture damage, not only in butterflies but also in fish [54], suggesting that butterfly and fish systems share a common mechanism of wound healing and color pattern development to some extent. Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms of color pattern development in butterfly wings have been studied intensively using several approaches, including comparative morphological approach [48,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71], surgical and physical approach [72,73,74,75,76], physiological approach [77,78,79,80], bioimaging approach [81,82,83,84,85,86], and genetic and molecular biological approach [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107], the wound-healing process itself has not been studied at the cellular level in butterflies.

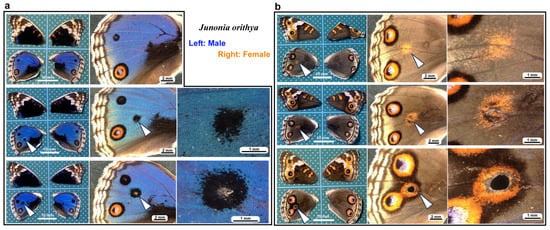

In the present study, we first demonstrated that puncture damage to pupal wing epidermal tissues induced wing repair and ectopic color patterns in our experimental species, Junonia orithya. Damage-induced ectopic color patterns in this species have already been demonstrated [51]; however, we first confirmed the ectopic color patterns here before proceeding with further experiments. Following this confirmation, we focused on cellular dynamics and calcium oscillations in pupal wing tissues after puncture damage using a bioimaging technique. The butterfly pupal wing system mainly contains only two types of cells: epidermal (epithelial) cells that constitute the wing epidermis and free-moving hemocytes, and we differentially stained these two types of cells. We further showed that a general calcium inhibitor, ruthenium red, affected wing scale development, although the effect of thapsigargin, an inhibitor of Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), on wing development in J. orithya has already been documented [52,108]. We then examined the effects of calcium inhibition by ruthenium red on damage repair and ectopic color patterns in the present study. The present results provide fundamental information on the process of wound healing in terms of cellular migration and calcium signaling in butterfly wings.

4. Discussion

We studied wound healing and the associated ectopic color patterns of butterfly wings, focusing on the cellular dynamics and calcium oscillations at the damage site by bioimaging techniques. Because we performed the puncture damage manually, we could not avoid the variability of the damage site in size and shape. This operational variability was probably reflected in the various levels of wing repair and ectopic color patterns among the treated individuals. It is likely that an individual with severe damage formed a large ectopic eyespot-like color pattern around an unsealed damage hole in adult wings, and that an individual with light damage formed a small ectopic color pattern (or no color pattern) without a scar or hole at the damage site in adult wings. Nevertheless, in most individuals that eclosed after the wounding operation, the damage was repaired completely with minor ectopic color patterns in adult wings in our experimental system, indicating that the wound-healing process was robust and normally executed in the treated individuals in our experimental system. Additionally, in terms of methodology, our staining procedures, including the differential staining method, were not perfect. We often observed that one of the two fluorescent dyes used simultaneously did not work well, and the sandwich method stained the hemocytes to various degrees. MitoRed-positive cells (i.e., hemocytes) and BODIPY-positive cells (i.e., epidermal cells) were successfully differentiated in size in the healing damage sites, as shown in Figure 3a, but not in Figure 3b. Nonetheless, we believe that our methodology was acceptable with careful interpretation, and that our differential staining method can be used for rough distinction between epidermal cells in the epidermis and hemocytes in the hemolymph. We did not intend to differentiate hemocyte subtypes in this study, but future studies may use some fluorescent dyes specific to subtypes of hemocytes. Bearing these points in mind, some of the findings of this study are illustrated in Figure 20.

As shown in Figure 20, we speculate the following time course of wound healing in butterfly pupal wing tissues. Before damage, an epidermal sheet is present in association with the pupal cuticle, and local hemocytes are present in the hemocoel [83,84]. Puncture damage breaks the pupal cuticle and underlying epidermis. Many epidermal cells nonetheless seem to be alive after damage, possibly contributing to temporary repair, including epithelial bridge formation (horizontal extension and connection among damaged but surviving epidermal cells in the damage hole) and cuticle block (secretion of the cuticle to temporarily seal the edge of the damaged tissue) around the edge of the damaged tissue, although this temporary repair process is speculative. At the same time, these epithelial cells emit calcium signals, which probably induce taxis signals such as hydrogen peroxide, although this is also beyond the scope of the present study. Local hemocytes in the hemocoel are quickly attracted to the damage site to execute phagocytic functions against invading microorganisms through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), together with the clearance of cell debris. In response to taxis signals that may be induced by calcium signals, additional hemocytes migrate mostly along the nearest wing veins (lacunae) to the damage site, as shown in the present study. These hemocytes may also clear cell debris but form cellular clusters together with surviving epidermal cells. Importantly, novel epidermal cells are then recruited to the damage site, further forming clusters. Epidermal cells secrete cuticle to repair the damaged cuticle, and the damage hole is sealed with epidermal cells, as shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. This scenario is largely based on the experimental results presented in this study, but includes our speculations, which should be verified or rejected in the future. The migrating cells via the wing veins in a long range in response to damage are likely plasmatocytes (and/or granulocytes) that can phagocytose cell debris and invading microorganisms [4].

The cell migration after damage observed in the present study was notable at the following five points. First, cell migration occurred mainly in defined directions from the nearest wing vein. This is somewhat surprising, considering that the taxis signals may be released randomly in all directions. Indeed, some cells seem to have arrived later at the damage site from different directions. Thus, wing veins may function as express highways for cell migration. In addition, cell migration has a long range, and the migration distance may be much greater than several hundred micrometers (Figure 4 and Figure 8). However, the fast migration of hemocytes along the wing veins is likely passive, because hemocytes are just circulating within the hemocoel. Once circulating hemocytes recognize a chemotactic signal from the damage site when they approach that site passively, they will probably leave the wing vein to travel to the damage site.

Second, migrating cells first arrived at the damage site as early as 15 min postwounding (63 min on average; n = 7) on the basis of time-lapse images, with the following arrival times: 120 min (Figure 4), 55 min (Figure 5), 95 min (Figure 6), 55 min (Figure 7), 65 min (Figure 8), 35 min (Figure 9), and 15 min (Figure 11). Early-arrival and late-arrival cells may be composed of different populations of hemocytes, and early-arrival hemocytes may be difficult to record; local hemocytes might have arrived even before that time to eradicate invading microorganisms. In insects, most bacteria (99.5%) invading the hemocoel are eliminated within 1 h of invasion [110].

Third, migrating cells settled at the center of the damage site or at the edge of the damage site, where they formed cellular clusters. The cellular clusters are reminiscent of the regenerative blastema observed in other regeneration systems [9,33,111,112]. Compared with the normal epidermis, the cellular clusters at the damage site seem to be composed of relatively large cells, and they were irregular in shape. The priority of the settlement position for migrating hemocytes seems to be given to either the center or the edge, probably depending on the presence of damaged cells releasing calcium signals or taxis signals.

Fourth, oddly enough, there was an acellular gap between the central and edge clusters in many cases. Alternatively, the damage hole was covered with cells without a gap. In our imaging system, wound healing did not proceed beyond this stage in some individuals and in that case, the physical gap between the central and edge clusters remained. We believe that this gap will eventually be covered by epidermal cells under normal conditions. If so, the damage hole is repaired not only from the edge but also from the central portion simultaneously. In many cases, the damage hole expanded over time, probably partly because of cell death at the edge of the damaged tissue and partly because of bleaching of the fluorescent dyes. In the case of the former, the repair process did not catch up with tissue degradation. However, in some other cases, the damage hole was completely covered with cells. A new cuticle seemed to be added to close the damage hole, as shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Fifth, not all damage holes attracted hemocytes. In an individual with three damage holes nearby, two were covered by cells, but the largest one was not covered at all (Figure 5). Overall, in our system, there were four states of wing repair: full coverage with epidermal central coverage (as shown in Figure 13), full coverage, central coverage, and no coverage. The four states of wing repair were schematically drawn in relation to the short diameter of the damage hole (Figure 21). It appears that small holes of 200 μm or less can attract hemocytes efficiently and be sealed by cells completely or partially, but large holes of 300 μm or more cannot always do so. When scores were given to the four states of wing repair, they were correlated with the size of the damage hole (Pearson correlation coefficient r = −0.40; n = 14), although it was not statistically significant (p = 0.15). It is likely that the larger damage holes were repaired less efficiently than the smaller holes. This interpretation is consistent with the interpretation of the results for the adult wings shown in Figure 1. Especially, the large damage holes without cellular coverage are consistent with the fact that we obtained adult wings with a large unsealed damage hole at the damage site (Figure 1 and Figure 19). Similarly, we speculate that the three consequences of wound healing in adult wings (i.e., sealed, scar, and hole) partially depend on the physical size of the damage hole but also on the availability of live epidermal cells that release calcium or other signals in the damage hole, which were not always visualized well in this study but likely existed in many individuals with complete coverage. The proliferation of epidermal cells may occur to cover the entire damaged area. However, we did not observe phenoloxidase-mediated melaninization of the damage site by hemocytes. We do not know whether this process is related to butterfly color pattern formation.

In the Drosophila wing imaginal disc, wound healing of an ablated portion has been studied intensively, in which an ablated portion is filled from the angular portion of the damage where two edges can meet within a small distance [12], which may be analogous to the cellular coverage from the edge to the center of the damage in the present study. The central coverage with an isolated cellular cluster observed in the present study may be unique to the wound-healing process of a puncture hole. In the Drosophila system, filopodia, actin cables, and proliferation of epidermal cells are known to be important [12], and will be examined in the future in our butterfly system. However, the contributions of hemocytes to the wound-healing process may not be well discussed in the Drosophila system. It would be interesting to observe the potential effects of hemocyte depletion on the wound-healing process in the future.

From the center and edge of the damage, we observed calcium oscillations, which were observed almost immediately after the wounding operation, likely before the beginning of cell migration. Thus, the release of calcium signals from the damaged epidermis may be the very early step of wound healing. Considering that calcium signals in butterfly pupal wings are relatively slow in propagation (1–10 μm/s) but travel long distances (more than 1 mm), according to a previous study [52], damage-induced calcium signals may be suitable for attracting hemocytes quickly from distant sources. In Drosophila pupal wing tissues, calcium signals are considered master regulators of wound healing [20]. This may also be true for butterfly pupal wing tissues. However, calcium signals are not able to attract hemocytes directly because the expansion of calcium waves is likely mediated by IP3 via gap junctions [21,22]. To attract hemocytes, signals must be mediated by hemolymph. In this sense, calcium signals may induce the release of other signaling molecules, such as hydrogen peroxide, to attract hemocytes [27]. However, calcium signals may directly mediate the migration of epidermal cells to the damage site. The migration of epidermal cells occurred later than that of hemocytes in the present study. In this event, which may be similar to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), epidermal cells must change their shape and size; relatively flat and large cells were observed at the damage sites in the present study, as shown in Figure 2. Under normal conditions without damage, epidermal cells in butterfly pupal wing tissues at this stage are vertically elongated, as revealed by real-time confocal microscopy [84,85] and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [109]. The formation of cellular clusters is likely an important step in the reconstruction of a new piece of epidermal tissue.

In the present study, calcium oscillations had peak intervals of approximately 5–7 min, but we also observed sharper oscillations with short intervals of 1–2 min, which may be called calcium spikes. Adjacent regions at or around the damage site appeared to exhibit largely synchronized oscillations. However, the central regions of the damage site had slightly higher amplitudes and earlier peaks in most cases, suggesting that oscillations can propagate as calcium waves from the center of the damage site. Moreover, calcium oscillations were not observed in ROIs a few hundred micrometers away from other active ROIs, suggesting that damage-induced calcium waves attenuate over distance and that the range of calcium wave propagation is limited, probably depending on the size of the damage hole, although this propagation range may still be considered a long range in comparison with the cell size. In our analyses, ROIs near the damage site most often had higher intensity changes than ROIs distant from the damage site, but this was not always the case, as shown in Figure 14h. This is probably because some cells near the damage site could not produce calcium oscillations due to severe damage. We did not record more than 180 min, but calcium oscillations seem to mostly cease within this time span, although this may be because of technical reasons such as bleaching of CalBryte and death of the damaged cells of the wing tissue.

Calcium oscillations might have originated from a cytoplasmic region near the ER membranes because CalBryte signals were colocalized with the BODIPY signal, an indication of intracellular membranous structures near the nucleus. However, the contribution of calcium ions from other sources to calcium oscillations cannot be ruled out. Moreover, we observed relatively large CalBryte-positive membrane-enclosed globules. These globular structures were highly positive for CalBryte, suggesting that they may function as calcium stores. These globules may have been previously reported as endosome-like structures but were mostly insensitive to various fluorescent dyes [84].

Considering that calcium signals may function to attract epidermal cells directly and hemocytes indirectly during wound healing, we speculate that during the normal development of butterfly wing color patterns, calcium signals from the eyespot organizer may initiate the migration of surrounding epidermal cells to the prospective eyespot focus to further augment the eyespot organizer. However, calcium signals seem to have multiple functions in butterfly wing development. To understand the physiological function of calcium oscillations, we used ruthenium red, which is known to inhibit various types of calcium transporters and channels, including ER Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), ryanodine receptors, mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporters, and TRP and Piezo mechanoreceptors [113,114,115,116,117,118,119]. As expected from a previous study [52], ruthenium red disrupted calcium oscillations in the present study, although the possibility of dislocation of the object cannot be excluded completely. The effect of ruthenium red seems to be transient; smaller spikes restarted within approximately 10 min after treatment in one individual (Figure 17c,d). This transient effect may explain why ruthenium red treatment did not affect healing efficiency under our experimental conditions. Similarly, ectopic color pattern induction by damage was not affected by the injection of ruthenium red, although we obtained one individual with an unsealed damage hole without ectopic color patterns after the injection of ruthenium red, in which ruthenium red might have suppressed the development of ectopic color patterns.

On the other hand, ruthenium red impaired normal scale development in terms of structural and pigment colors and potentially enlarged eyespots in size, suggesting that calcium signals play important roles in various aspects of scale development and color pattern formation in the normal development of butterfly wings. Interestingly, structural colors in butterfly wing scales are produced by the microarchitecture of actomyosin and chitin complexes [120,121]. Calcium is a well-known regulator of actomyosin contraction and relaxation in the muscles [122,123]. If this is applicable to butterfly wings, it is conceivable that in butterfly wings, calcium signals drive the actomyosin complex for normal scale development. However, this potential function of calcium in scale development must be executed a few days postpupation when scales are produced. Thus, aberrant phenotypes induced by ruthenium red may be unrelated to the calcium signals observed during the wound-healing process in this study. Nonetheless, we believe that calcium signals in wound healing drive actomyosin complexes to mechanically close the wound.

Actomyosin-driven mechanical forces play important roles not only in wound healing in Drosophila [10,14,15,16,17] but also in the development of many other biological systems. During morphogenesis, the developing epithelium is under compression, which causes mechanical buckling of the epithelium, as shown in the suspended epithelia of the canine kidney [124]. Buckling forces in two-dimensional epithelium may be employed in morphogenesis to produce folds and other complex structures in many developmental systems, including the brain, intestine, and lung [125]. In an organotypic culture of mouse embryonic submandibular glands, buckling forces are provided by the actomyosin complex, which then promotes branching of this epithelial organ [126]. According to a simulation study, an actomyosin ring is likely responsible for epithelial folding [127]. Gastrulation is initiated by a propagating furrow, which is initiated by epithelial buckling in Drosophila embryos [128]. Importantly, to drive this buckling, embryo-scale force balance is necessary and sufficient [128]. Similar to mechanical force, calcium waves promote apical extrusion of cells from the epithelium in cultured cells and zebrafish embryos [129,130]. In these systems, IP3 receptors and gap junctions are involved in calcium wave propagation [129], similar to the Drosophila wound-healing system [21,22,23].

Calcium signals are likely used in normal color pattern formation in butterflies because spontaneous calcium waves are released from the center of the prospective eyespot (i.e., the eyespot organizer) [52]. At the prospective eyespot focus, eyespot organizing cells form a cellular cluster underneath the pupal cuticle spot, which physically distorts the wing epidermis [69,70,71]. This physical distortion may be an initiator of calcium signals from the eyespot organizer and vice versa, which is called the distortion hypothesis [64]. Theoretically, physical distortions can include epithelial thickening, buckling, furrows, and waves driven by actomyosin or other cytoskeletal filaments, which are reminiscent of the differentiation waves proposed by Gordon [131,132,133,134]. Evolutionarily, this distortion mechanism may be considered a co-option of wound-healing mechanisms, and damage-induced ectopic color patterns in butterflies may be considered a consequence of this evolutionary co-option [97]. The fact that calcium signals are a driver of the actomyosin complex might have made it easier for butterflies to evolve structural color in scales because scales require the actomyosin complex. Similarly, this calcium–actomyosin relationship might have made it easier for butterflies to evolve complex color patterns that require the actomyosin complex for physical distortions. Interestingly, thapsigargin-treated Junonia almana individuals presented a “reversed-type” color pattern modification, which tends to enlarge eyespots [135], and thapsigargin-treated Vanessa cardui can recapitulate its sister species, Vanessa kershawi, in terms of wing color patterns [136]. These studies suggest that calcium signals can be employed to determine and diversify wing color patterns across species.

Source link

Shuka Nagai www.mdpi.com