1. Introduction

The demand for alternative animal-free foodstuffs is currently on the rise. Consequently, new strategies need to be found for sustainable agriculture and the associated demand for alternative protein sources [

1]. In this context, bioproduction technologies offer a promising solution approach, particularly in milk protein production, as a scalable and cost-effective method for alternative protein production [

2,

3].

Bovine milk provides one of the most important sources of proteins, essential fatty acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals [

4,

5]. In terms of protein availability, casein represents around 80% of the total protein amount in bovine milk. Caseins are secretory proteins, which are post-translationally modified by phosphorylation (α

S1-, α

S2-, and β-casein) of serine residues and glycosylation (κ-casein) of threonine residues [

6,

7]. These proteins are characterized by their ability to form colloidal nanostructures called micelles—a key feature for many of their applications [

8,

9,

10]. Its natural origin and non-toxicity make it also an ideal candidate for encapsulating and protecting pharmaceuticals, ensuring controlled release and enhanced bioavailability of drugs [

11,

12].

However, the post-translational modifications (PTMs) and high aggregation propensity make microbial casein bioproduction difficult. Microbial hosts often lack the necessary machinery to perform PTMs such as phosphorylation, which impairs the solubility and functionality of recombinant proteins [

13]. In microbial expression systems, this often leads to the formation of inclusion bodies, in which the proteins are misfolded and biologically inactive, making their recovery and purification difficult [

13,

14]. The formation of micelles, which is crucial for the function of caseins in dairy products, is another challenging issue [

15].

Nevertheless, the expression of α-, β-, and κ-casein was previously carried out in microbes such as

E. coli,

S. cerevisiae, and

P. pastoris [

16,

17,

18,

19]. In most studies, only the expression of these proteins was detected, while titers and yields were rarely reported. Exemplarily, Choi and Jiménez-Flores [

19] reported a titer of 245 mg/L of bovine β-casein using

P. pastoris strain GS115 in a five-day culture in buffered minimal methanol medium for the production. Wang et al. [

20] achieved in a cultivation with artificial wheat straw hydrolysate medium, using the

E. coli strain BL21(DE3) as the production strain, bovine α

S1-casein titers of 1.13 g/L. However, although those microbes are used by various start-ups, among others, for the production of animal-free, but animal-like foods from purified proteins [

21], challenges in production inefficiency due to insufficient expression systems and adaptation of posttranslational target protein modifications, identification of cost-effective downstream processing strategy including purification methods such as gel filtration, ion exchange chromatography, hydrophobic chromatography and affinity chromatography, and food safety evaluations in terms of allergenicity or toxicity to consumers by carrying out a risk assessment (genetic engineering, stability of the product, dietary nutrition, toxicity, sensitization) are still present [

3,

21].

In this context, the application of

B. subtilis, as a super-secreting cell factory [

22,

23], allows the bioproduction of different recombinant proteins.

B. subtilis also appears to be a promising host for the recombinant expression of food additives, as some of the products are generally recognized as safe (GRAS), which may also improve public acceptance of microbially produced food proteins as a key to their success [

24]. In this context, the formation of target proteins and localization/accumulation in inclusion bodies using a microorganism that is harmless to humans might be another beneficial strategy for the microbial production of food additives [

25,

26]. In addition,

B. subtilis allows the formation of high biomass in adapted high cell density fed-batch bioreactor fermentation processes using sporulation-deficient production strains [

27,

28]. For instance, Tran et al. [

29] showed the potential of

B. subtilis as a production strain for recombinant proteins using the strong IPTG-inducible P

grac100 promoter system, leading to 20.9% of the target protein compared to the total intracellular protein amount after 12 h of induction time [

29]. In contrast, Scheidler et al. [

26] developed an efficient amber suppression system in

B. subtilis using IPTG as an inducer, enabling the production of proteins with non-canonical amino acids. In this way, a notable yield of 2 mg/L could be achieved for the light chain variable domain of a murine monoclonal antibody fragment (MAK33-VL) [

26]. Overall, it is noticeable that

B. subtilis expression systems are mostly carried out in complex medium but not in defined mineral salt media. However, this is required for establishing high cell density cultures. To enable further improvements in product yield, native auto-regulatory cell density coupling expression systems were utilized in protease-deficient

B. subtilis strains, such as

B. subtilis WB600 and WB800, although these strains did not lead to a high overall production yield of recombinant proteins [

30].

In addition, laboratory

B. subtilis strains, such as strain 168 and its derivative 3NA, were used for the bioproduction of valuable bioactive metabolites and enzymes [

28,

31,

32]. Moreover, genome-reduced

B. subtilis strains allow further potential for optimization due to a clean secondary metabolic background, a lack of extracellular proteases, prophages, and key sporulation genes [

33,

34]. In this way, genome reduction is a promising strategy to obtain higher protein concentration by partial removal of the production strain chromosome [

35]. The most genome-reduced

B. subtilis strain to date is PG10, which lacks approximately 36% of the genome [

36]. In general, genome-reduced strains are mostly used to express difficult-to-produce proteins, as these strains are described to have an increased translation efficiency and lower production of proteases [

36]. However, genome reduction also affects the physiological properties of

B. subtilis, resulting exemplarily in an inability of

B. subtilis strain PG10 to grow on mineral salt medium, as reported by Lilge and Kuipers [

37]. However, Aguilar Suárez et al. [

38] showed that the genome-reduced

B. subtilis strains, such as the

B. subtilis strain IIG-Bs-27-39, are partly able to grow on minimal medium. Accordingly, production strains are needed that have the advantages of both genome-reduced and wild-type strains, which makes so-called midi-

Bacillus strains interesting production strains [

39].

In this study, the potential of B. subtilis with its status as a partially FDA-approved bacterial strain was used for the first time as a host for the bioproduction of the difficult-to-produce bovine αS1-casein protein. For this purpose, the potential of controlled genome reduction was combined with the principle of target protein accumulation in inclusion bodies. Therefore, the strains BMV9, a derivative of the non-sporulating B. subtilis 3NA, and the genome-reduced midi-B. subtilis strain IIG-Bs-20-5-1 were applied. In subsequent high cell density fermentation processes with chemically defined mineral salt medium in 42 L fed-batch bioreactor systems, insights were provided into an upscaling production process for bovine αS1-casein as a main protein component of cow’s milk. Finally, zeta potential and particle size were measured for a pre-cleaned B. subtilis protein mixture with abundant recombinant casein product and compared to an αS1-casein reference protein.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals, Materials, and Standard Procedures

Chemicals used were purchased from Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany), Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (Hercules, CA, USA), and Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). A standard of his6-αS1 casein was achieved after cultivation of a heterologous E. coli production strain BL21 DE3 (Gold), followed by protein purification using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) with Ni-NTA columns (HisTrap HP, 5 × 5 mL nickel column; GE Healthcare Life Sciences; Chicago, IL, USA) and an ÄKTA chromatography system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA). An anti-His tag antibody (mouse) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was used for Western blot approaches. A bovine αS1-casein reference standard (Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG; Karlsruhe, Germany) was used for comparative analyses of protein properties.

2.2. Strains, Plasmids, and Conditions of Cultivation

The strains and plasmids used in this study are provided in

Table 1.

2.3. Cloning Procedures

Standard molecular methods were conducted as described before by Sambrook and Russell [

43]. Oligonucleotides used for cloning procedures are provided in

Table S1. The gene sequence of a codon-optimized α

S1-casein gene version (

Figure S1) synthesized by Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany) was cloned into the pHT254 plasmid system, allowing an N-terminal his

8-tag protein fusion and an IPTG-inducible gene expression using a P

grac100 promoter region [

25]. Therefore, the codon-optimized α

S1-casein gene (603 bp) was amplified from the previously synthesized plasmid “pEX-A128-alpha S1 casein” with the oligonucleotides Casein_pHT_I_FOR and Casein_pHT_I_REV using Q5-polymerase (New England Biolabs; Ipswich, MA, USA). The plasmid backbone of pHT254 was amplified using the oligonucleotides Casein_pHT_V_FOR and Casein_pHT_V_REV. Purification of PCR products was carried out with the QIAquick PCR and Gel Cleanup Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were fused using the Gibson Assembly Master Mix from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, except for an extended incubation period of up to 3 h of the final reaction mixture [

44]. Ligation mixtures were transformed using competent

E. coli BL21 Gold (DE3) cells. Recombinant clones were screened by colony PCR using

Taq 5x Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), and the cloned expression plasmids were confirmed by Sanger sequencing at Eurofins GmbH (Ebersberg, Germany).

2.4. Bioproduction of Recombinant Bovine αS1-Casein

In shake flask cultivations, the pre-culture was prepared in LB medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 5 g/L NaCl) supplemented with 5 µg/mL of chloramphenicol as a selection marker and was cultivated at 37 °C and 120 rpm overnight in an incubator shaker (NewbrunswickTM/Innova® 44, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). For the main culture, cells from the pre-culture were inoculated in TB medium (24 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L glycerol, 0.017 M KH2PO4, 0.072 M K2HPO4) supplemented with chloramphenicol (5 µg/mL) as a selection marker to an optical density (OD600nm) of 0.1. The subsequent cultivation process was performed as described before. The target gene expression was induced at an OD600nm of about 1.0 using 1 mM (w/v) of sterile filtered isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranosid (IPTG). The induction was carried out for 20 h.

Bioreactor cultivations were carried with the genome-reduced

B. subtilis strain IIG-Bs-20-5-1 according to descriptions from Klausmann et al. [

27]. The initial pre-culture was performed in L -medium. The second pre-culture was inoculated in mineral salt medium, consisting of 5.5 g/L glucose × H

2O, 4 g/L Na

2HPO

4, 14.6 g/L KH

2PO

4, 4.5 g/L (NH

4)

2SO

4, 0.2 g/L MgSO

4 × 7 H

2O, 3 mL/L trace element solution (TES) and 25 g/L (

w/

v) glucose. TES contained 40 mM Na

3citrate, 5 mM CaCl

2, 50 mM FeSO

4, and 0.6 mM MnSO

4 × H

2O. Media used for fermentation processes were previously described by Willenbacher et al. [

45] and Wenzel et al. [

46]. Bioreactor cultivations were performed in a 42 L fermenter (ZETA GmbH, Graz/Lieboch, Austria) filled with 12 L batch medium using 25 g/L (

w/

v) of glucose as carbon source. The temperature was set to 37 °C, pH to 7.0, and initial stirrer speed to 300 rpm. A minimum dissolved oxygen level of 40% was achieved by modifying the stirrer speed and aeration rate. Initially, the aeration rate during the batch phase was set to 2 L/min and subsequently increased up to 22 L/min after starting the feeding process. Fed-batch phase was started after glucose depletion using a feed solution with 50% (

w/

w) glucose. In addition, 1.44 g/L IPTG was added to the feed solution. The bioreactor experiments were performed in biological duplicates.

2.5. Sampling and Sample Analysis

Samples were taken at least every two hours after the induction and were analyzed regarding the OD

600nm values and the corresponding biomass. The OD

600nm was determined using a spectrophotometer (UV-3100 PC; VWR GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Cell dry weight was calculated with a correlation factor of 4.31 obtained by drying the biomass for 24 h at 110 °C and weighing the dried cell pellet. The cell pellet was harvested via centrifugation at 4 °C and 10,000×

g for 10 min (Microcentrifuge 5430R; Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). A subsequent mechanical cell disruption was carried out using 0.1 mm glass beads (Disruptor Beads 0.1 mm, Scientific Industries, Inc.; New York, NY, USA) or a high-pressure homogenizer (APV 2000; SPX Flow Technology Rosista GmbH, Unna, Germany). After cell disruption, remaining cell components, including the insoluble proteins, were separated from the soluble protein fraction by centrifugation. The resulting pellet was dissolved in the same volume of 8 M urea solution to obtain the insoluble protein fraction. The protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay (Roti

® Quant; Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany) [

47]. The determination of protein sizes was performed using SDS-PAGE with 4–20% polyacrylamide gels (TGX Stain-Free™ FastCast™ Acrylamide Solutions; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and Coomassie staining (Roti

®-Blue quick; Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG; Karlsruhe, Germany).

After gel electrophoresis, the gels were used for Western blot analysis using nitrocellulose/filter paper sandwiches (0.45 µm, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and a wet-type blotting system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The transfer buffer used consisted of 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, and 20% (v/v) methanol with a pH of 8.3. Gels, membranes, filter paper, and fiber pads were equilibrated and soaked in transfer buffer before assembly. The transfer was performed at 30 V for 1 h. After transfer, the membrane was blocked for 1 h in 10 mL PBS buffer containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween20 and 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin on a shaking plate, before 3 µL of the primary antibody (mouse anti-histidine tag antibody, clone AD1.1.10, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; Hercules, CA, USA) was added and incubated for 1 h on the shaking plate. The membrane was then rinsed 4 times with deionized water. For detection, 5 mL of the ready-to-use Novex® Chromogenic Substrate (Invitrogen Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) was added to the membrane and incubated for 3 min. The reaction was stopped by rinsing the membrane with deionized water. The Coomassie-stained gels and Western blot were scanned using a gel documentation system (Quantum ST5; Vilber Lourmat Deutschland GmbH, Eberhardzell, Germany). To detect the amount of produced and his-tagged αS1-casein target protein, samples were purified with HisPur™ Ni-NTA Spin Columns (0.2 mL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the protein amount was subsequently quantified.

2.6. Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography

For increasing the abundance of the recombinant α

S1-casein in the

B. subtilis protein mixture, the bioreactor culture (

Section 2.4) was harvested, and the resulting biomass pellets were stored at −20 °C. Subsequently, a thawed cell pellet was resuspended in 10 volume units of 10x ice-cold binding buffer (20 mM Na-phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 8 M urea, 40 mM imidazole, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) as a protease inhibitor. Cell disruption was performed in a high-pressure homogenizer (APV 2000, SPX Flow Technology Germany GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany) with five cycles at a pressure of 1400 bar. To separate the insoluble protein fraction, the crude cell extract was centrifuged with a flow rate of 100 mL/min at 4 °C and 25,000×

g (Heraeus Contifuge Stratos, 3049 (HCT 22.300) rotor, Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH, Waltham, USA), and the insoluble fraction was resuspended in the same volume of binding buffer. Afterwards, immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) was performed to increase the abundance of the α

S1-casein target protein in the

B. subtilis protein mixture, using an automated chromatography system (ÄKTA™ start; Cytiva Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). A pre-packed 20 mL HisPrep™ FF 16/10 column preloaded with Ni Sepharose™ 6 Fast Flow was used to capture the recombinant protein. The column was equilibrated with five column volumes (CV) of binding buffer. Unbound proteins were washed out with approximately 10 CV of binding buffer. The bound protein fraction, including the α

S1-casein fraction, was eluted with a one-step gradient (100%) of elution buffer (20 mM Na-phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 8 M urea, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.4). The pooled fractions were processed to remove imidazole with buffer exchange using PD-10 desalting columns (Cytiva Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). The recovery procedure was performed in technical duplicates.

2.7. Quantification of Intracellular αS1-Casein

The protein concentration at different time points and the purity was determined in the insoluble fraction of the intracellular proteome using GelAnalyzer 23.1.1 (available at

www.gelanalyzer.com by Istvan Lazar Jr., PhD and Istvan Lazar Sr., PhD, CSc). Samples were taken after induction, and the his-tagged α

S1-casein was purified using 0.2 mL His-Trap Spin Columns (

Figure S4). SDS-PAGEs (

Figure S4) were scanned at 600 dpi, and band intensities were quantified. For each lane, the intensity of the target band and the total intensity of all visible bands were measured. Automatic band detection was performed, and thresholds were adjusted to accurately capture all visible bands while excluding background artifacts. The relative intensity of the target band was calculated as follows:

The amount of the target protein was determined by multiplying the relative intensity by the total protein amount:

As a reference protein, an in-house expressed and purified His(6)-α

S1-casein standard from Wang et al. [

20] was used. All measurements were performed in duplicates.

2.8. Data Analysis

For the estimation of production performances, the yield of product per biomass (

YP/X), product per substrate (

YP/S), biomass per substrate (

YX/S), and the intracellular volumetric casein titer were calculated using the equations below. Therefore, the parameters biomass (

X), glucose as substrate (

S), and casein as product (

P) were used.

2.9. Zeta Potential and Particle Size Distribution

Zeta potential and particle size were measured with a Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK) and evaluated with the corresponding Zetasizer Software 7.2. Measurements were carried out in triplicate at 25 °C in disposable folded capillary cells. Measurements were exerted at a laser wavelength of 633 nm. Zeta potential determination was applied with an angle of 90°. Particle size was determined via dual-angle dynamic light scattering (DLS) at 13° and 173°. The measurement is dependent on laser scattering, and accordingly the refractive index of the solution and dispersant must be considered. A value of 1.33 was chosen for water and 1.57 for α

S1-casein, which is a generic refractive index used for proteins [

48]. Protein solutions with a concentration of 0.2% (

w/

w) were used for measurements. Changes in pH were performed stepwise from pH 7 to pH 3.

4. Discussion

Finding new expression strains is a crucial step in the development of new biotechnology-based principles for food protein production. In this context,

B. subtilis provides a good baseline as a well-established expression host for recombinant protein production, as summarized by Souza et al. [

49], and is partially accepted as a GRAS microorganism. Here, genome minimization was previously described as a promising approach for developing platform strains for difficult-to-produce proteins with a clean secondary metabolic background [

33,

34]. However, as genome reduction also affects physiological properties of

B. subtilis, as shown for

B. subtilis strain PG10, the most genome-reduced

B. subtilis strain to date [

36]. Accordingly,

B. subtilis strains revealing less genome reduction seem to be promising for future bioproduction processes, making so-called midi-

Bacillus strains interesting production strains for difficult-to-produce bioproducts [

39].

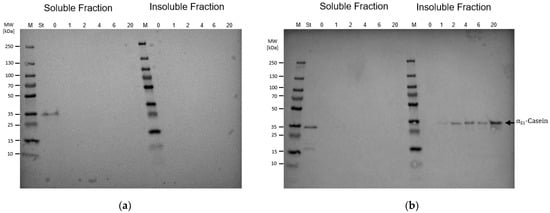

In this study, the potential of the genome-reduced midi-

B. subtilis strain IIG-Bs-20-5-1 was used for the recombinant bioproduction of the difficult-to-produce bovine α

S1-casein [

41]. The

B. subtilis strain BMV9, a sporulation-deficient and surfactin-producing derivative of

B. subtilis strain 3NA, was used as a reference strain. Interestingly, although the selected

B. subtilis strains differ in about 10% of genome complexity, only midi-

B. subtilis strain IIG-Bs-20-5-1 allowed a detectable intracellular α

S1-casein bioproduction, while absolutely no target protein detection was observed for

B. subtilis strain BMV9 (

Figure 1). The partial genome reduction in the

B. subtilis strain IIG-Bs-20-5-1 includes the deletion of genes encoding for the biosynthesis of the non-ribosomally produced metabolites plipastatin, bacilysin, and polyketides, but also lacks the biosynthesis of the antimicrobial substances subtilosin A, kanosamine, and the

Bacillus toxin Sdp, but also several genes encoding for prophages and the alternative sigma factors SigE and SigG [

41,

50]. In contrast to the strain IIG-Bs-20-5-1, the 3NA derivative BMV9, which was optimized for high cell density cultivations, features a point mutation in the

spo0A gene locus and a 33 bp-comprising elongation of the

abrB gene. These point mutations make the

B. subtilis strain BMV9 a promising surfactin production strain in high cell density fermentation processes [

40]. However, although only the midi-

Bacillus strain allowed the bioproduction of α

S1-casein as the target protein, it is not clear whether the sole reduction in metabolic side-streams or deletion of certain genes achieved the bioproduction. Nevertheless, this work provides

B. subtilis the first time as a production strain for recombinant casein bioproduction. However, especially genome-reduced

B. subtilis strains were previously described as an attractive chassis for recombinant protein production. In this context, Schilling et al. [

34] demonstrated that genome reduction in

B. subtilis leads to significantly improved secretion and protein activation of disulfide-linked proteins. Aguilar Suárez et al. [

38] also showed that genome reduction promotes the production of recombinant proteins, including extracellular protein IsaA and extracellular staphylococcal target proteins. Furthermore, it was shown that a guided genome reduction as in strain IIG-Bs-27-39 offers significant advantages in terms of growth, metabolic efficiency, and stability of protein production. These results provide the way for the further increase in recombinant casein production [

38].

In the subsequent upscaling of bioproduction processes, the cultivation of a genome-reduced

B. subtilis strain using large-scale fed-batch bioreactor fermentation was described for the first time in the scientific literature (

Figure 2), showing the potential of genome-reduced

Bacillus strains as viable platform organisms for large-scale, difficult-to-produce protein biosynthesis. This scalability is crucial for the transition from laboratory-scale experiments to industrial applications, highlighting the broad industrial relevance of

B. subtilis in biotechnological applications.

However, since an α

S1-casein accumulation in the insoluble protein fraction was found, a subsequent complete purification needs a laborious downstream purification. Nevertheless, a first pre-cleanup was performed using urea as a chaotropic agent for denaturing proteins in inclusion bodies and ÄKTA-mediated affinity chromatography for targeting the his-tagged α

S1-casein. Based on this pre-cleanup, an accumulation of the α

S1-casein with a purity of 46.5% and a titer of 2.16 mg

Casein/g

CDW could be achieved (

Figure 3). Further improvements of the titer might be available in protease-deficient

B. subtilis strains. In this context, Duanis-Assaf et al. [

51] stated the capability of

B. subtilis to degrade other casein subunits (κ-casein). Since the α

S1-casein target protein was only detectable in the insoluble protein fraction,

B. subtilis proteases, like Clp proteases, might actively degrade the unstructured α

S1-casein version [

52]. In another study, Airaksinen et al. [

53] described the intracellular bioproduction of

Chlamydia pneumoniae proteins in secretory protease-deficient

Bacillus subtilis strains WB600 and IA289 with localization of the proteins MOMP and Omp2 in the inclusion bodies and Hsp60 in the soluble cytosolic fraction [

53]. However, the intracellular accumulation of α

S1-casein also provides the basis for the formation of micelle-like structures if co-expression of further casein subunits occurs.

In comparison, the results in our work show the successful production of recombinant bovine α

S1-casein in

B. subtilis, a species that is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) [

54]. This makes the production of food proteins in

B. subtilis particularly attractive. In combination with a robust cell growth, the use of high cell-density fermentation processes and further flexible genetic engineering approaches,

B. subtilis is an ideal candidate for the bioproduction of food proteins. Only the downstream processing with respect to the localization of casein in inclusion bodies appears to require further research in order to be able to make final recipe formulations. Nevertheless, a pre-cleaning by using urea as a chaotropic agent and an immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) was performed, which led to a target protein purity of 46.5% and a production yield Y

P/X of 1.6 mg casein per gram cell dry weight (CDW) (

Figure 3a). To further improve downstream processing, modification of parameters such as pH and salt concentration, the addition of dithiothreitol to the elution buffer, or changing the affinity tag might solve this problem [

55]. However, the establishment of an individual target protein-specific downstream processing was not the goal of this work and needs to be addressed in future studies.

Nevertheless, to characterize the pre-cleaned recombinant casein protein mixture, zeta potential measurements and particle size determinations were performed using native bovine α

S1-casein as the reference. In this way, the pre-cleaned recombinant α

S1-casein protein mixture and native bovine α

S1-casein revealed significant modulation of surface charge properties with pH. Higher zeta potential values at lower pH were attributed to protonation of acidic residues, with a marked decline as the pH approached the isoelectric point (IEP). The IEP was identified at pH 5.0–5.5 for pre-cleaned recombinant α

S1-casein protein mixture and at pH 4.0–4.6 for native bovine α

S1-casein reference, consistent with previous studies [

56,

57]. Beyond the IEP, the stabilization of surface charge at higher pH may reflect maximum charge repulsion or new intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding or van der Waals forces [

58]. Notably, native bovine α

S1-casein exhibited more negative zeta potential values at higher pH compared to the pre-cleaned recombinant protein version.

In contrast, the pre-cleaned protein mixture with abundant recombinant bovine α

S1-casein displayed a sharp increase in particle size between pH 3 and 5, likely due to reduced electrostatic repulsion and increased hydrophobic interactions as net charge decreased, consistent with observations in milk-based systems by Rojas-Candelas et al. [

59]. In contrast, the native α

S1-casein reference protein showed relatively stable particle sizes across pH levels [

15].

These results indicate that the remaining

B. subtilis proteins in the pre-cleaned recombinant casein mixture significantly affect the aggregation behavior of the produced α

S1-casein, leading to a greater tendency to aggregate compared to their native bovine reference substance. Furthermore, the increased particle size variability observed in the pre-cleaned recombinant casein protein mixture at lower pH values could be due to partial aggregation or denaturation of

B. subtilis proteins combined with the casein target protein, which exposes hydrophobic cores and leads to unpredictable aggregation patterns [

60,

61]. Accordingly, more efficient downstream processing for casein protein products needs to be established, as the observations in

Figure 4 indicate that the casein protein properties and aggregation behavior in response to pH changes are significantly different between the pre-purified recombinant casein protein mixture and the reference casein substance.