Achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 will require removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s foremost authority on the topic. But only some types of carbon removal are actually effective — and these are largely not the kind that major companies are investing in.

A new report from the NewClimate Institute, a European think tank, finds that 35 of the world’s biggest businesses are leaning on short-term tree-planting and other forms of “nondurable” carbon removal in order to say they’ve neutralized some of their climate pollution. The handful of companies investing in more reliable carbon removal are mostly not doing so in conjunction with deep decarbonization, or the elimination of carbon emissions altogether.

There is a “dangerous mismatch between corporate climate claims and the reality of what is needed to reach global net-zero,” the organization said in a press release. Reaching net-zero by the middle of the century — a scenario where all unavoidable human-caused climate pollution is canceled out via carbon removal — is considered necessary to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

Carbon dioxide removal, or CDR, refers to efforts to capture CO2 after it’s been emitted into the atmosphere and store it in rocks, land, ocean reservoirs, or human-made products. The most reliable types of carbon removal, which the NewClimate Institute calls “durable CDR,” involve injecting carbon into geological formations or turning it into rocks, where it will stay put for at least 1,000 years — about the same amount of time that CO2 from the burning of fossil fuels will remain in the atmosphere.

Currently, these durable techniques don’t work at scale: They account for just 0.1 percent of global carbon removal each year. The rest is based on methods like planting trees, restoring wetlands, and burying carbon in the soil, which are much cheaper but can only keep carbon out of the atmosphere for decades or a few centuries at most.

Government investment and regulations are needed to scale up durable CDR — experts consider the next decade to be “crucial” for developing the technology — but the private sector can help too, by funding durable CDR projects and research. In industries like construction, for which total decarbonization is not yet possible, companies will likely need to use durable CDR to offset residual emissions as part of a credible climate strategy.

The NewClimate Institute authors looked at 35 of the world’s largest companies across seven sectors: agrifood, aviation, automobiles, fashion, fossil fuels, tech, and utilities. Tech companies showed the most investment in durable CDR — Microsoft alone is responsible for 70 percent of all durable CDR ever contracted — but the report criticizes the sector for planning to claim “potentially significant amounts” of both durable and nondurable CDR toward net-zero targets. Tech companies can fully decarbonize without offsets, so their emissions targets should not depend on carbon removal.

Aviation was the other sector showing the greatest support for durable CDR, but only one airline — Japan’s All Nippon Airways — had a “reasonable” plan to use the technology to neutralize residual emissions by 2050. Three airlines lacked concrete plans.

Of the 15 companies across the agrifood, automobiles, and fashion sectors, only H&M and Stellantis are investing in durable CDR. Two of the five utilities in the report, Eon and Orsted, are supporting durable CDR projects, but it’s unclear whether Eon intends to use removals to count toward its net-zero goal, and the NewClimate Institute says some of Orsted’s removals are being double-counted in the emissions reduction targets of both Denmark and Microsoft. The five fossil fuel companies analyzed — Equinor, Exxon Mobil, Shell, Sinopec, and TotalEnergies — are focusing mostly on carbon capture and storage, which intercepts CO2 at the point of emission, before it escapes into the atmosphere, and does not reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

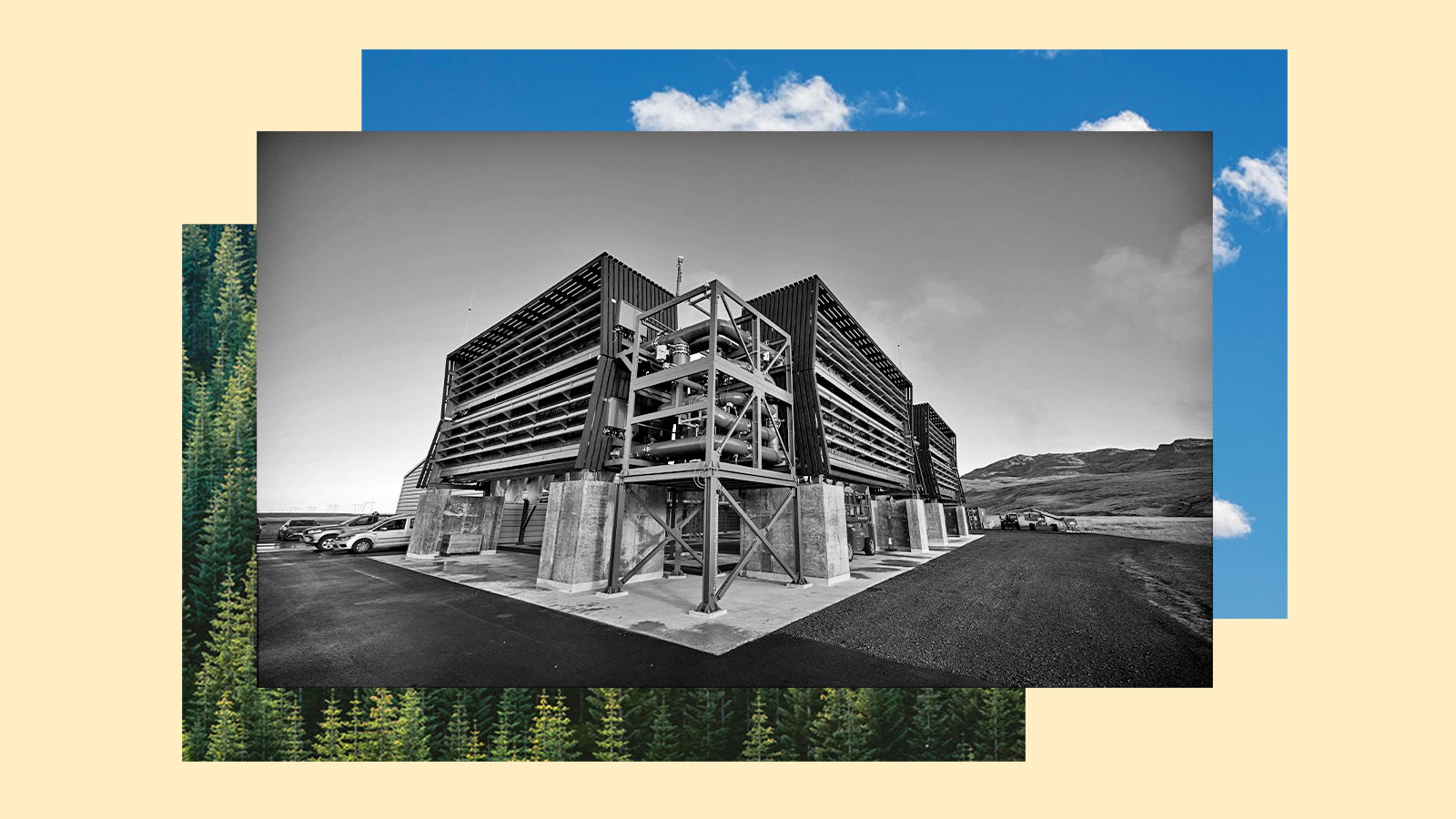

John Moore / Getty Images

Silke Mooldijk, an expert with the NewClimate Institute and the lead author of the new report, said she wasn’t surprised to find limited support for durable CDR, except from some tech companies. What did surprise her was that companies investing in durable CDR projects did not publicly report any information on these projects’ environmental and social risks. Some CDR methods, for example, may jeopardize biodiversity, while others require large amounts of renewable energy that would have to be diverted from other uses. “Not a single company in our report disclosed details on potential risks of projects they support and how they mitigate those,” Mooldijk told Grist.

Grist reached out to all 35 companies included in the report. Adidas, Amazon, Enel, Google, H&M, Inditex, Microsoft, and TotalEnergies responded by describing their net-zero commitments. Adidas and Enel, which are not currently investing in durable CDR, said they would use “high-quality” carbon removals to offset their residual climate pollution after taking actions to decarbonize; Inditex said it is “exploring” durable CDR to offset residual emissions, and its use of the technology “will be determined by the evolution of reference scientific frameworks.”

Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and H&M are currently investing in durable CDR. A spokesperson for H&M described the fast-fashion company’s purchase of 10,000 metric tons of durable CDR from the Swiss company Climeworks, one of the largest purchases to date, and said H&M plans to use them to neutralize residual emissions. The tech companies affirmed their commitment to reduce emissions first and then use carbon removal to offset residual emissions, though none of them addressed NewClimate Institute’s concerns that they would use large amounts of durable and nondurable CDR to claim progress toward net-zero.

A statement provided to Grist from TotalEnergies did not address CDR. It instead described the company’s support for carbon capture and storage and “nature-based solutions.” The latter refers to short-lived offsets, such as tree-planting, that the NewClimate Institute does not believe are appropriate for offsetting fossil fuel emissions.

Apple, Duke Energy, Google, and Shein declined to comment after seeing the report. The remaining 24 companies did not respond to inquiries from Grist.

Jonathan Overpeck, a climate scientist at the University of Michigan and the dean of its School for Environment and Sustainability, said the NewClimate Institute report is timely. “Right now the whole idea of CDR … is kind of a Wild West scene, with lots of actors promising to do things that may or may not be possible,” he said. He added that companies appear to be using CDR as an alternative to mitigating their climate pollution.

“The priority has to be on reducing emissions, not on durable CDR at this point,” he told Grist.

In the near term, durable CDR is doing virtually nothing to offset emissions. As of 2023, only 0.0023 gigatons of CO2 were removed from the atmosphere each year using these methods. That’s about 15,000 times less than the annual amount of climate pollution from fossil fuels and cement manufacturing.

According to the NewClimate Institute, voluntary initiatives are no substitute for government-mandated emissions reduction targets and investments in durable CDR. To the extent that these initiatives exist, however, the organization says they should provide a clearer definition of what constitutes “durable” carbon removal; determine companies’ responsibility for scaling up durable CDR based on their ongoing and historical emissions, or — perhaps more realistically — on their ability to pay; and require companies to set separate targets for emissions reductions and support for durable CDR. The last recommendation is intended to reinforce a climate action hierarchy that puts mitigation before offsetting. Companies should not “hide inaction on decarbonization behind investments in removals,” as the report puts it.

Mooldijk said voluntary initiatives can incentivize investments in durable CDR by recognizing “climate contributions.” These might manifest as simple statements about companies’ monetary contributions to durable CDR, instead of claims about the amount of CO2 that they have theoretically neutralized.

Some of these recommendations were submitted earlier this year to the Science-Based Targets initiative, the world’s most respected verifier of private sector climate targets. The organization is getting ready to update its corporate net-zero standard with new guidance on the use of CDR. Another standard-setter, the International Organization for Standardization, is similarly preparing to release new standards on net-zero, which could curtail some of the most questionable corporate climate claims while also drumming up support for durable CDR.

John Reilly, a senior lecturer emeritus at the MIT Sloan School of Management, said that ultimately, proper regulation of corporate climate commitments — including of durable CDR — will fall on governments. Companies “are happy to throw a little money into these things,” he said, “but I don’t think voluntary guidelines are ever going to get you there.”

Source link

Joseph Winters grist.org