The Glacier Mass Balance Intercomparison Exercise, or GlaMBIE—a European Space Agency project launched in 2022—aims to strengthen global glacier monitoring by combining field observations with satellite-based data from remote sensing technologies. By bringing together researchers and institutions from the scientific community, the project seeks to identify gaps in the global monitoring record and future challenges to the field. The findings of the first stage of GlaMBIE, published in Nature this year, show that since 2000, glaciers have lost about five percent of their mass globally, with some regions having lost up to 39 percent.

GlaMBIE has entered the research scene during a critical time: continued funding for crucial glacier monitoring technologies is uncertain, and the magnitude of global glacier decline in the 21st century has been historically unprecedented—reinforcing glaciers as clear indicators of ongoing anthropogenic climate change. Glacier monitoring is essential for tracking glacier mass changes over time, and GlaMBIE’s assessment is important to ensuring the continuity of this data, especially when many glacier monitoring technologies are expected to be suspended or decommissioned due to U.S funding cuts.

The results of GlaMBIE’s first stage highlight the need to secure the future of glacier monitoring technology. The urgency of the project stems from the varied impacts of melting glaciers. They contribute to global sea level rise and also impact local and regional water resources, high mountain ecosystems and habitats, and the frequency and intensity of natural hazards. Monitoring glaciers and their decline is crucial to understanding these impacts and creating solutions at the local, regional and global levels.

GlaMBIE’s work seeks to improve the collection of data on glacier mass balance, which is the yearly difference between how much snow a glacier accumulates and how much ice it loses. It is indicative of a glacier’s health: a positive balance means a glacier is gaining mass, while a negative balance shows that a glacier is shrinking. It can be measured and monitored through fieldwork or remote sensing technologies.

Fieldwork involves tasks like researchers hiking out onto a glacier and creating a grid of stakes across a glacier’s surface. Using the grid, scientists can measure changes in the glacier’s surface level over time using the stakes as reference points. The point measurements for each stake can be analyzed across the grid and used to calculate the overall mass balance of the glacier. While fieldwork measurements are highly accurate and can provide precise data about local conditions, they are limited in scope compared to remote sensing technologies.

Accessing remote, high-altitude glaciers can be dangerous, expensive and time-consuming; sometimes it is impossible. These constraints mean that only a small share of the world’s glaciers can be monitored using field observations, leading to difficulty in calculating glacier mass changes on regional or global scales. For this reason, glacier monitoring efforts have largely shifted in the last few decades to rely more on remote sensing technologies, which provide a larger spatial context and coverage than field observations.

Several types of satellite-based technologies have shaped modern glacier monitoring, each with different strengths and limitations. To develop an accurate assessment of global glacier mass balance changes and identify gaps in glacier monitoring data, the GlaMBIE team gathered observations from a wide range of remote sensing technologies. In light of shifting priorities—with global increases to military budgets and decreases in science funding—the continued availability of these technologies is uncertain, underscoring the importance of GlaMBIE’s work.

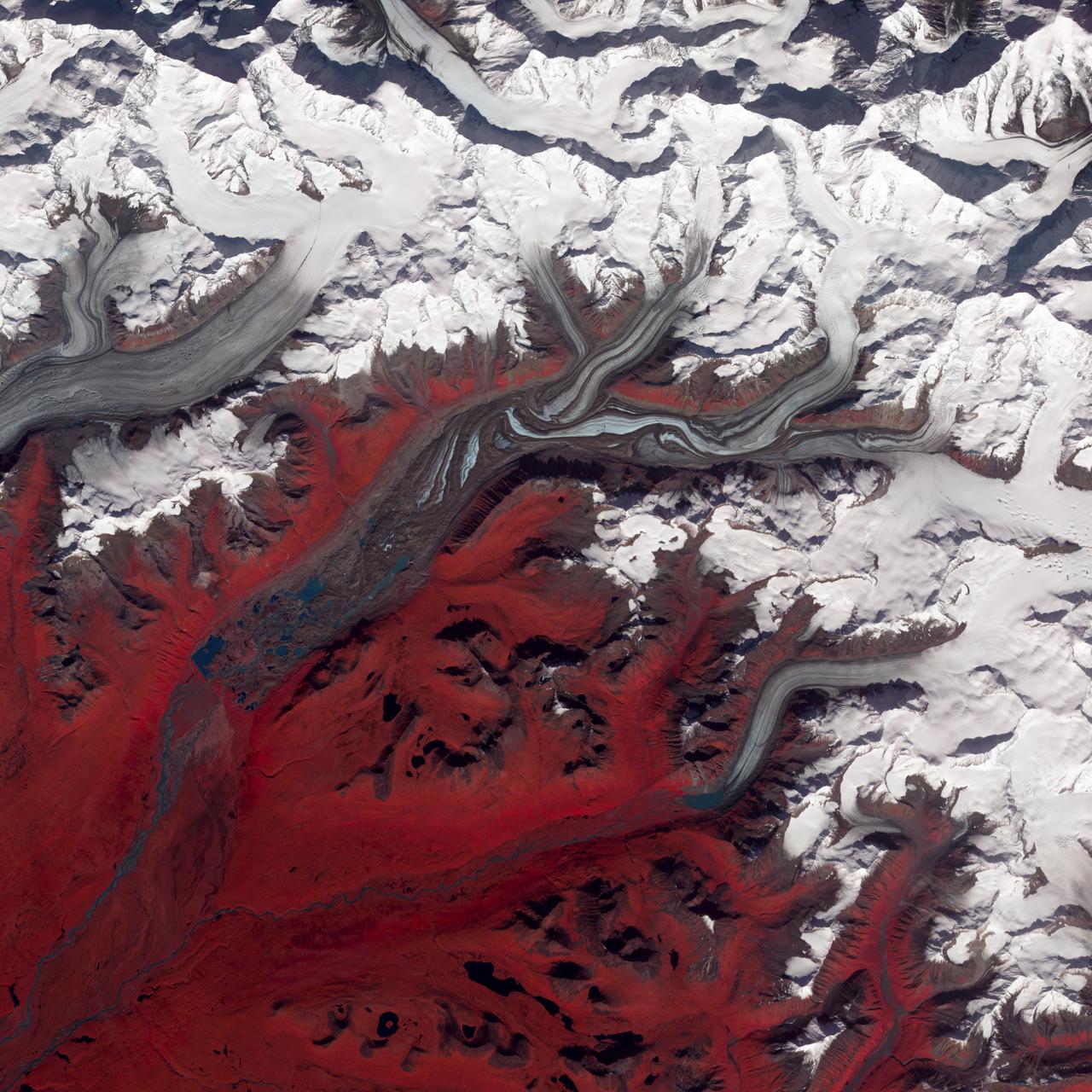

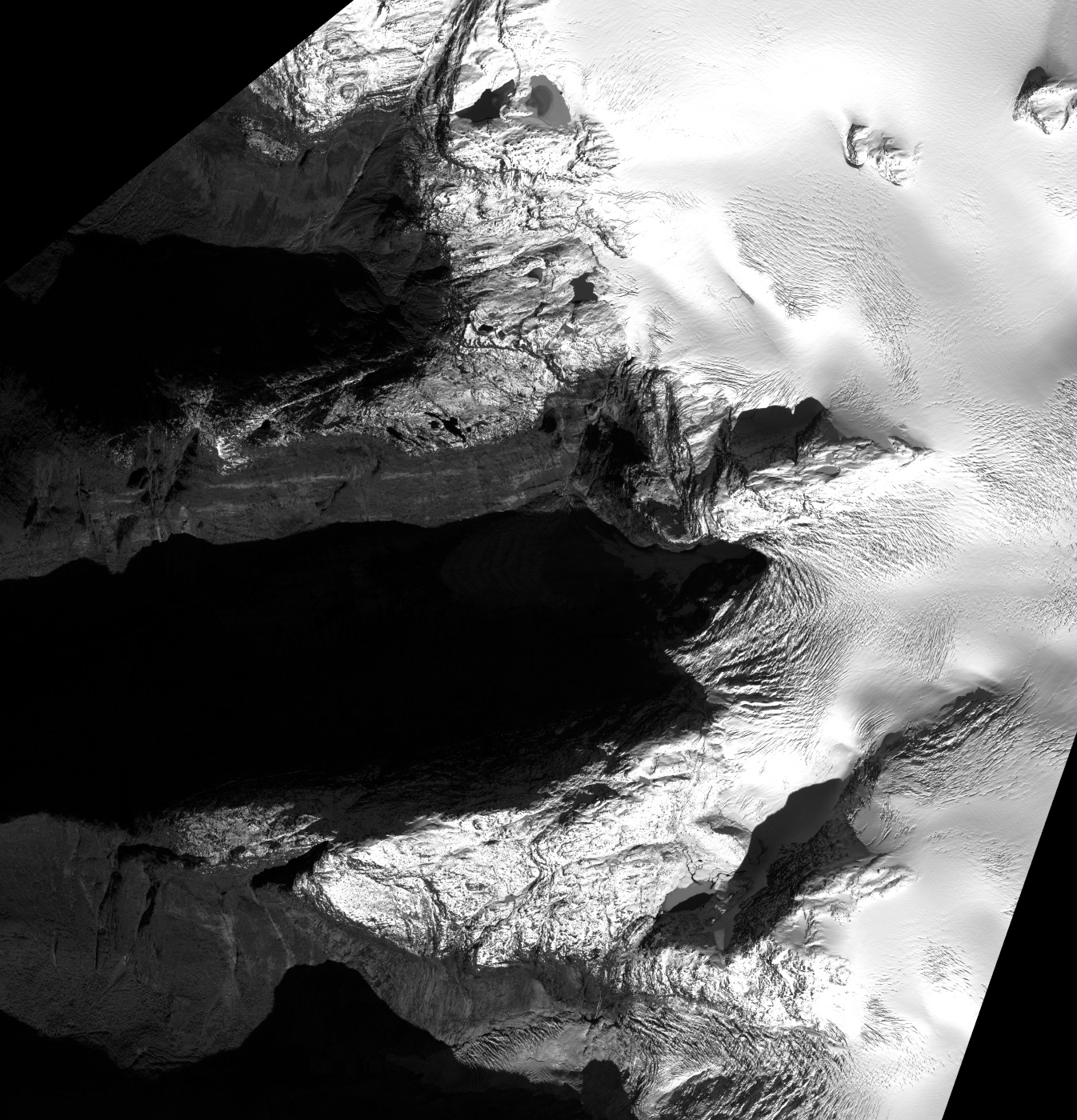

Optical sensors—such as those in NASA’s ASTER mission—capture high-resolution visible and infrared images that allow scientists to map glacier extent and track the movement of glacier fronts, though darkness and atmospheric conditions can limit data collection. Elevation changes are measured through radar and laser altimetry missions like CryoSat-2 and ICESat-2, which send pulses toward the Earth’s surface and record the return time to determine a glacier’s height. Radar altimetry can penetrate snow and cloud cover, making it especially useful in the polar regions. Another approach, gravimetry—used by the GRACE and GRACE-FO missions—measures changes in Earth’s gravity field caused by ice loss, allowing scientists to calculate mass loss across entire mountain ranges and ice sheets, though at a coarser spatial resolution.

Neither fieldwork nor satellite observations are sufficient on their own. As glaciologist Marco Tedesco, a research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, which is part of the Columbia Climate School, explained in an interview with GlacierHub, “a truly comprehensive understanding of glaciers…hinges on a strong combination of fieldwork and remote sensing technologies.” He said that while fieldwork allows us to “gather detailed information, observe firsthand and develop a contextual understanding that’s simply impossible to achieve from afar,” remote sensing allows us to “see patterns…and collect data on a scale that’s simply unattainable through traditional on-the-ground methods.”

Tedesco’s explanation highlights why remote sensing is crucial to glacier monitoring efforts. Satellites can continuously track vast and inaccessible areas, providing critical data needed for understanding large-scale glacier change, beyond what fieldwork alone can do.

By combining observations from satellites using the technologies described above and fieldwork measurements, the GlaMBIE team worked to establish a “new community estimate of regional and global glacier mass changes and related uncertainties.”

In addition to quantifying glacier mass loss, the team outlined key challenges that must be addressed to secure the future of glacier monitoring. These include opening access to historical archives to expand the observational record, expanding and updating field observations in data-poor regions, and ensuring long-term continuity of satellite missions across all technologies. Many current missions are set to conclude in the next few years, and continuing missions need to be initiated soon. Some remote sensing technologies are expected to be suspended—such as the NASA Terra satellite’s ASTER—or decommissioned due to U.S funding cuts, underscoring the need for new missions to collect open-access data in these areas.

Despite the fact that glaciers are rapidly losing mass due to climate change, Tedesco emphasized that “continuing to monitor glaciers, even if their future seems bleak, is crucial.” He noted that “it’s not just about fixing problems; it’s about understanding the impact of these changes on individuals and communities.”

Securing the future of glacier monitoring will require a global effort, with scientists and government working together to expand monitoring capabilities and data availability, ensuring a better understanding of the impacts of glacier decline and providing solutions for communities. Without the collective will and funding necessary to ensure the continuity of crucial remote sensing technologies, humanity will lose essential data and insights needed to support these communities and adaptation efforts.

Source link

Guest news.climate.columbia.edu