1. Introduction

Mosquitoes are vectors of dangerous epidemic diseases. Traveling and global warming help in expanding vectors such as

Aedes, Anopheles, and

Culex spp. all over the world [

1,

2].

Aedes aegypti, the principal vector of the dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever viruses, poses considerable public health challenges globally. The tropical and subtropical climate of Egypt creates an ideal environment for

Aedes aegypti proliferation, particularly in urban areas, where water storage practices and inadequate drainage facilitate breeding [

3]. Recent studies have confirmed the establishment of

Aedes aegypti in various regions of Egypt, including the Red Sea Governorate [

3,

4]. The re-emergence of this mosquito species in Egypt has been linked to climate change, which has expanded its range and increased the risk of dengue outbreaks [

5]. This necessitates the exploration of innovative and sustainable control measures.

The excessive use of chemical insecticides harms human health and the ecosystem [

6], so there is an urgent need for alternative control strategies that are effective and environmentally friendly. Developing insecticides from plant sources may reduce the negative effects caused by such chemicals.

Chlorophyll derivatives, as natural porphyric compounds, have been explored as effective photosensitizing agents for controlling medical and agricultural pests [

7]. A novel method has been developed using these porphyric derivatives as sunlight-activated insecticides for the outdoor control of harmful insects [

8]. Photosensitizers are known to absorb various wavelengths across the solar spectrum. This allows them to undergo highly efficient photoexcitation with sunlight and generate a high quantum yield of singlet oxygen (

1O

2) and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) when exposed to light. These reactive species can potentially damage and kill specific stages of insects [

9]. Some photo-pesticides have been identified as promising larvicides for controlling

Anopheles spp. [

10,

11]. Chlorophyllin is a water-soluble derivative of chlorophyll. Compared to chlorophyll, chlorophyllin is more hydrophilic, possesses coloring capabilities, and is more stable in acidic media and light [

12]. Chlorophyll derivatives, as potential larvicides, offer additional benefits such as cost-effectiveness, as well as being naturally sourced from green plants and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as food additives (E 170) [

8,

9]. Chlorophyllin has not been demonstrated as sufficiently insecticidal against various arthropod vectors, and its application against

Aedes aegypti larvae, particularly in a semi-field setting, has not been extensively studied. Furthermore, understanding the genotoxic potential of chlorophyllin is crucial for assessing its safety and suitability as an alternative larvicidal agent. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of chlorophyllin in controlling

Aedes aegypti larvae under semi-field conditions, and to critically assess its genotoxic impact. By addressing these objectives, we seek to contribute to the development of environmentally safe and effective strategies for managing

Aedes aegypti populations in Egypt, ultimately enhancing public health outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pesticides Used

2.1.1. Chlorophyll Derivative Preparation (Ch-L)

Chlorophyll was extracted from plant leaves (

Spinacia oleracea; family: Amaranthaceae) and vegetable peels. A semi-synthetic combination of sodium–copper complex made from plant-extracted chlorophyll is known as chlorophyllin. In this process, the copper atom replaces the magnesium atom in the center of the chlorophyll, which no longer has a phytol tail [

13,

14]. Ethanol (65%) was added to the collected plant leaves before being pulverized with a mortar and pestle and heated to 60 °C in a water bath for 10 min. NaOH (20 mL-5%) was added for the saponification process, with constant stirring. The preparation was centrifuged for 10 min at 4500 rpm. After gathering the supernatant, CuSO

4 (15 mL of 20%) solution was added. After 30 min in the water bath, Cu-chlorophyllin was extracted. Then, 2% NaOH solution was added, reaching pH 9.6, and soluble Na-Cu-chlorophyllin complexes were prepared. They were then centrifuged for 15 min at 4500 rpm. The pellets were collected, allowed to dry, and then stored in vials for further investigations [

15].

2.1.2. Pheophorbide

Pheophorbide was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Taufkirchen, Germany) and is recognized for its photodynamic activity; it has a photodynamic activity due to generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) under light. This feature is connected to its toxicity.

2.1.3. Bacillus sphaericus (Bs)

A subculture of the larvicidal bacterium B. sphaericus was obtained from the Microbiological Resources Centre (Cairo Mircen), Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University. It was kept as a slant in our lab, and different concentrations were prepared for bioassay.

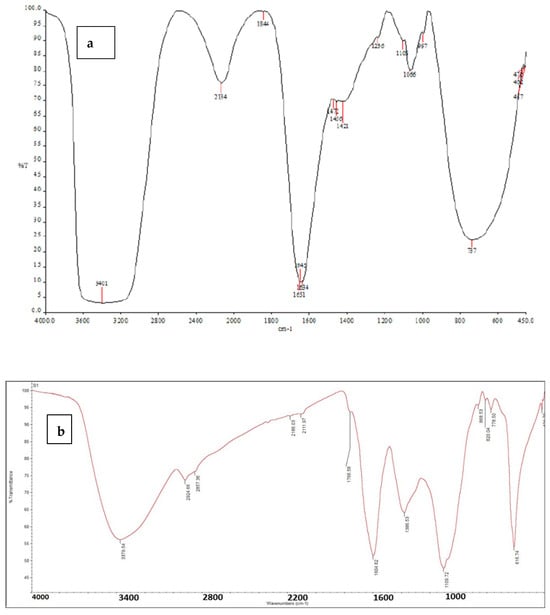

2.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR was used to investigate the secondary metabolites, functional groups, and structural features of chlorophyllin. The calculated spectra reflect the well-known dependence of chlorophyllin’s optical properties by measuring infrared intensity against the wavelength of light, as described by Baker et al. [

16] and Khan et al. [

17].

2.3. Singlet Oxygen (1O2) Quantum Yield QΔ of Chlorophyllin

One gram of prepared chlorophyllin was dissolved in distilled water. The specimen was subjected to a Shimadzu UV-1900 UV-VIS Spectrophotometer (Livingston, UK) to collect the steady-state absorption spectra, and a Hamamatsu H10330-45 NIR detector was used in the emission mode to collect singlet oxygen (

1O

2) decay at 1270 nm at the Chemistry Lab in the Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, as previously described [

18,

19]. The excitation source was a Q-smart Nd: YAG Quantel Laser (Lumibird, Lannio, France) at 355 nm. The singlet oxygen quantum yield was determined by comparing the luminescence intensity of singlet oxygen at 1270 nm photosensitized by chlorophyllin in aqueous with that obtained from the reference phenalenone, which is a universal reference compound with value = 1.0 for the determination of quantum yields

QΔ of singlet oxygen, with a remarkable capacity to transfer energy from its triplet excited state to the ground-state molecular oxygen, to finally produce

1O

2 in a process called photosensitization, with very efficient sensitization [

20].

2.4. Mosquito Rearing

Field-collected larvae were used to raise a laboratory colony of

Aedes aegypti, and then the females were allowed a blood meal from a pigeon. The second generation was selected for the experiments. All of the experiments were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions at 27 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 5% RH, and a 14:10 h light/dark photoperiod [

21].

2.5. Laboratory Evaluation of Used Bio-Pesticides

Bioassays were conducted to evaluate the toxicity of chlorophyllin, pheophorbide, and Bacillus sphaericus against third-instar Aedes aegypti larvae. Different concentrations of each larvicide (chlorophyllin: 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 3 ppm; pheophorbide: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ppm; Bacillus sphaericus: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ppm) were prepared. Glass beakers with 100 mL of distilled water received 20 third-instar larvae of Aedes aegypti and one milliliter of the tested substance. Distilled water alone was utilized as a control. Three replications of each treatment and control were made. Chlorophyllin was incubated in the dark for about 18 h and then exposed to sunlight.

Larval mortality was recorded 24 h post-exposure based on loss of any movement, even after a mild touch with a glass rod [

22,

23]. The mortality rate was corrected and plotted against concentrations. LC

50 and LC

90 values were estimated for each larvicide and used for the field applications.

2.6. Field Evaluation of Used Pesticides

Semi-field experiments were applied in three different sites in the Hurghada region, Red Sea Governorate, Egypt, which were previously examined as positive sites for

Aedes aegypti breeding [

3]. One liter of unfiltered water from town cesspits serving as

Aedes aegypti breeding sites was introduced in plastic containers and implanted in the same breeding places to be exposed to the same environmental conditions. The cesspit water contained suspended matter, organic compounds, and debris. Fifty larvae per liter of cesspit water were introduced into each plastic bowl at 10 p.m. in full darkness.

Guided by the laboratory LC90 values, different concentrations of each tested bio-insecticide (chlorophyllin: 10, 50, 100, 200, 300 ppm; pheophorbide: 20, 50, 100, 200, 300 ppm; Bacillus sphaericus: 200, 300, 400, 500, 600 ppm) were prepared and applied at a volume of one milliliter to 100 mL of water in each bowl, and they were then exposed to natural sunlight from sunrise to sunset. Control experiments were performed in the absence of chlorophyllin, pheophorbide, and Bs. Mortality readings were recorded after 24 hr., corrected, and used to calculate field values of the LC50 and LC90, toxicity index, and relative potency.

2.7. Calculating the Toxicity Index and Relative Potency

Toxicity index formula [

24]:

2.8. Genotoxicity Studies

The effect of chlorophyllin application (compared with pheophorbide and

Bs) on the DNA configuration of treated

Aedes aegypti 3rd-instar larvae after 24 h of exposure was studied using the Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) PCR technique. DNA extraction was performed using the Dneasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Taufkirchen, Germany). DNA was extracted as described by Nieman et al. [

25], while the PCR cycles were performed as described by Williams et al. [

26]. The primers used during amplification, along with their sequences, are tabulated in

Table 1. List of the primer sequences used for RAPD-PCR). The similarity index quantifies the degree of band sharing between individuals and is calculated using the following formula:

where N ab represents the number of bands common to individuals a and b, while Na and Nb denote the total number of bands present in individuals a and b, respectively [27].

2.9. Histopathological Changes

Histopathological examinations of chlorophyllin-treated third-instar mosquito larvae after 24 h of exposure were conducted following the methodologies described by Farida et al. [

28] as routine preparations of microscopic slides to assess tissue alterations.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Based on the control treatments, Abbott’s formula [

29] was used to obtain the corrected mortality percentages. Using Analyst Soft Biostat Pro V 5.8.4.3 Software, the dose–response relationship curve was statistically estimated by probit analysis [

30] to determine each insecticide toxicity line’s regression equation components and lethal concentrations.

4. Discussion

The re-emergence of

Aedes aegypti within the Red Sea region in Egypt [

3] encouraged us to apply photosensitizers against

Aedes aegypti larvae as vector of dengue fever in Egypt. Chlorophyllin is a photosensitizer and a water-soluble analog of the famous green pigment chlorophyll [

31]. Pheophorbide is an intermediate product in the chlorophyll degradation pathway [

32].

This study employed a multi-faceted approach to investigate chlorophyllin’s potential efficiency as a novel control agent against the larvae of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. First, we characterized the key properties of chlorophyllin, including its singlet oxygen quantum yield, and evaluated its larvicidal efficacy under controlled laboratory and semi-field conditions. Second, we investigated the genotoxic effects of chlorophyllin on Aedes aegypti larvae using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD)-PCR. Finally, a histopathological analysis of the treated larvae was conducted to further understand the mechanism of action and identify the pathogenicity.

Our results demonstrated that chlorophyllin (Ch-L) could kill mosquito larvae in a few hours after exposure to sunlight under laboratory and semi-field conditions, with the lowest LC

50 values compared with pheophorbide or

Bs. Wohllebe et al. [

33] found that chlorophyllin at 8 ng was enough to induce photodynamic damage and death in mosquito larvae. We prepared chlorophyllin in our laboratory from the peels and leaves of vegetables, and then we used it to prepare a Cu-Mg chlorophyllin derivative, which proved its high toxicity. Trials to control mosquitoes using porphyrin, Rose Bengal, and xanthene as photosensitizing agents were previously carried out by Younis et al. [

34] and Meier and Hillyer [

35]. The larvicidal activity of Ch-L against water-dwelling disease vectors was also proven by Abdel-Kader et al. [

8] and Elshemy et al. [

36]. Some factors interfere with the photodynamic activity of chlorophyllin, such as the concentration of photosensitizers used, accumulation of chlorophyll derivatives (incubation in the dark), and light exposure period; longer incubation in the dark and more prolonged exposure to light increase larval mortality [

9]. We assumed that chlorophyll derivatives need to spread inside the larval body before starting the photodynamic reaction. Abdel Kader and El-Tayeb [

8] deduced that chlorophyll products could kill mosquito larvae in the presence of solar radiation after incubation in the dark. Erzinger et al. [

37] showed that, in

Chaoborus sp., a dark incubation period of about 3 h is sufficient to induce mortality of about 90%.

Most cell and tissue components are unsuitable acceptors of electronic energy from

3Sens (triplet excited state of photosensitizer), since their triplet states are too energetic. O

2 represents ground-state oxygen. Energy transfer occurred from the triplet excited state of the photosensitizer to ground-state oxygen, so singlet excited oxygen was formed, whose energy level lies at only 22.5 kcal [

38].

Estimating the quantum yield of chlorophyllin is critical to showing its photodynamic properties. By measuring the efficiency of chlorophyllin in transferring energy from the triplet excited state of the photosensitizer to ground-state oxygen, singlet excited oxygen was formed. Chlorophyll’s photodynamic interaction generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive singlet oxygen that can cause structural disintegration, leading to cell necrosis and apoptosis [

39,

40].

We used the RAPD-PCR technique to detect any alterations in the treated larvae’s DNA produced by environmental genotoxic stress. This technique was previously used to monitor DNA changes by Gupta and Preet [

41]. The genotoxicity results proved that chlorophyllin did not induce DNA alterations or mutations when compared with other mosquitocides, such as pheophorbide. Treatment with

Bs could alter the DNA configuration in an obvious way. This is one of the important advantages of using chlorophyllin in insect control.

Histopathological signs proved that chlorophyllin is a gut poison that interrupts epithelial cells’ integrity and leads to cell apoptosis. Fat and muscle tissues were also affected. Histopathology proved significant damage to the alimentary canal and its architecture. Some similar pathological evidence was found by [

42,

43,

44], who recorded tissue disruption after the treatment of mosquitoes with different plant extracts.

We concluded that chlorophyllin is a stomach poison and represents a new approach in insect control. Chlorophyllin is a promising mosquito larvicide with many advantages. Derivatives of chlorophyll do not harm vertebrates or humans, for example, as chlorophyllin is an approved food ingredient (E 170) [

9,

45]. They also do not pose any toxicity to non-transparent bodies. Chlorophyll derivatives can be easily extracted from various plant resources, and this approach appears to have economic value. Chlorophyll derivatives are sufficiently active to cause photodynamic death even in small quantities. Photosensitive chlorophyllin degrades very fast, without the formation of toxic byproducts, making it environmentally sound and economically safe [

33].