1. Introduction

The Global Burden of Disease study states smoking is the third leading risk factor for deaths and disability in the world [

1]. However, of all people, on a global level, health professionals are not immune from smoking. Like others, healthcare workers also have a tendency to smoke [

2] despite being aware of its well-known deleterious effect on health, and also on their image as role models to patients [

3]. The influence of smoking habits among healthcare professionals can compromise their public perception and health promotion roles, as their professional position may at times conflict with their personal choice of smoking [

4]. Studies have revealed statistically significant associations between physicians’ smoking status and beliefs and their clinical practice [

5,

6].

There is also evidence that smoking cessation advice from a health professional has a positive effect on their patients or community [

7,

8], as smokers who rely on the support and advice of their healthcare provider have more chances to quit than those who try it on their own [

6,

9]. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) also specifically stresses the importance of healthcare workers setting an example by not using tobacco [

10]. Smoking by health professionals may then undermine their health promotion role and send a key message to smokers that smoking is a healthy choice [

11].

In the same context, it is also important to understand why healthcare workers continue to smoke and what the drivers for such behavior are. It was not unfamiliar even in the earlier days to use physicians/health workers in cigarette advertisements. Through the early 1950s, it was a strategic response by the tobacco companies to devise advertising directly to physicians; the doctors’ image was good for them (tobacco industries) to normalize smoking and also to assure the consumer that their brands were safe [

12]. Indeed, the majority of the physicians used to smoke then, as described in the article ‘The Doctors’ Choice is America’s Choice!’ [

12]. But why would physicians, nurses, or health workers per se continue to smoke despite knowing smoking is harmful? Is it just an addiction or enjoyment that drives them like the general people [

13], or perhaps they consider it important, but not a priority [

14]? Studies would narrate, among other reasons, a possible stressful working environment, peer pressure, socioeconomic status, or education as some of the possible predictors [

14,

15]. It is imperative to know whether these and other variables in regard to smoking change over time, place, or geographic locations because they might provide a behavioral/motivational ladder to locate their blockage for change and/or design help specifically addressed to them [

14].

Historically, there has been a decline in smoking rates among healthcare professionals in many countries. However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of tobacco use among healthcare workers showed varying degrees of smoking prevalence across nations. It showed that among high-income countries, the mean smoking prevalence among healthcare workers was lower than the general population, except in Australia, Italy, and Uruguay [

10]. The lowest prevalences (<5%) were observed in the US and Ireland, and the highest were (30%) in Greece, Croatia, Italy, and Uruguay. Among upper-middle-income countries, the lowest prevalences (<30%) among healthcare workers were observed in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, and the highest was (40%) in Turkey [

10]. Among lower-middle-income countries, the lowest smoking prevalence (<10%) was noted in India and the highest (>50%) in Pakistan [

10]. So, despite all the anti-smoking campaigns and policies and local, national, and international legislations and commitments, the decline in tobacco smoking prevalence has not been symmetrical or proportional across regions, including those among the healthcare groups. Public health efforts have also historically focused on smoking cessation programs for the general population . Healthcare workers, who are at the forefront of providing smoking cessation counseling services to the patients or community, have not been a focus of tobacco control initiatives [

4,

16]. Also, when we talk about interactions with patients on smoking cessation, it is not only the physicians or nurses but an array of other health service provider groups as well. However, evidence on smoking prevalence or their correlates as such for this wider group of healthcare workers is generally lacking. The existing literature is either based on sporadic cross-sectional studies or, in some cases, analyses from longitudinal data on smoking prevalence. Australia, in this regard, is not an exception either.

Australia has a unique healthcare environment. Although physicians and nurses constitute the two largest professional groups in the Australian healthcare system [

11,

17], there are other health service providers who are well positioned to offer smoking cessation advice to patients. They include dentists, midwives, psychologists, optometrists, occupational therapists, mental health workers, pharmacists, physician assistants, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners (AHWs), as they are on the frontlines of primary care [

18,

19]. The importance of the AHWs should not be undermined, as they play a crucial role in delivering a range of services and health information to the Indigenous communities [

20]. They are a subgroup often overlooked in research but who nevertheless face daunting challenges in regard to smoking cessation or the cultural context of smoking within Aboriginal communities.

Although Australia is one of the countries where smoking rates have declined consistently and considerably over the years because of its very early and stringent tobacco control policies and legislations, like many other countries, information from across the employee spectrum of the Australian health workforce is very limited [

21]. Nationally representative surveys in Australia, such as the National Health Surveys (NHS) or the National Drug Strategy and Household Surveys (NDSHS), do not provide statistical information for disaggregated groups of people that represent healthcare providers [

22]. Combating tobacco smoking among health professionals requires the availability of current data on their smoking behavior. Factoring smoking prevalence trends and possible reasons for such behavior and their impact on health efficacy, recent public health campaigns, and technological advancements in data collection and shifting societal attitudes toward smoking in healthcare, it is imperative that we assess the smoking behavior among the wider health professional groups in Australia.

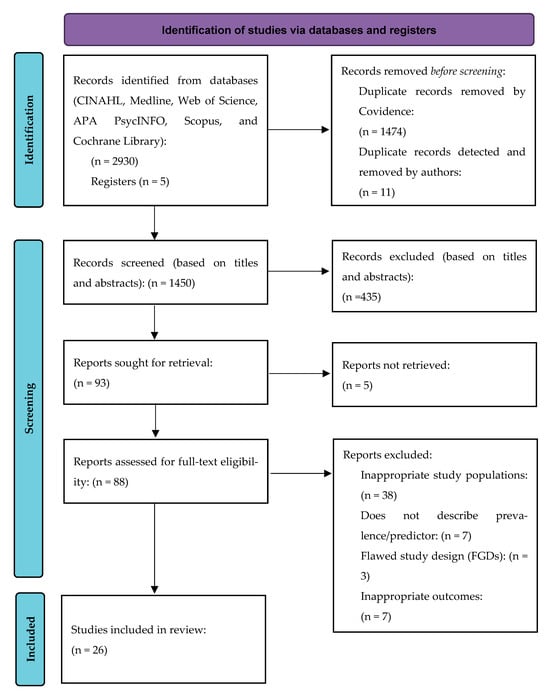

To address this gap in research, we aimed to undertake a comprehensive scoping review. The primary objective was to explore the prevalence of smoking among healthcare professionals in Australia. The secondary objective was to identify the factors influencing the smoking habits among these health professionals. The uniqueness of this review will be the novel methodological perspective, including the wide range of workforce in the country and underrepresented groups like AHWs. Addressing the gaps may also lead to some actionable outcomes, such as informed tailored interventions or policy changes. To recognize an evidence-based literature range, and also follow the PCC (population, concept, and context) framework [

23], this scoping review’s research question was developed as follows:

What does the academic literature say about the prevalence and predictors of smoking among healthcare professionals in Australia?

4. Discussion

The prevalence of smoking among healthcare providers is a public health issue both for themselves and for their patients because they play a key role in combating the use of tobacco [

56]. Even an earlier study conducted in a major hospital in Australia showed that non-smoking healthcare workers were more likely than smokers to see helping patients who wanted to quit smoking as definitely part of their role [

57]. Overall, this review presents a picture of physicians, nurses, midwives, dentists, optometrists, and Aboriginal Health Workers (AHWs) in Australia in regard to their smoking prevalence and predictors of such behavior. Although this review explored all the literature available within this timeframe, except for one study conducted on AHWs, this review failed to identify recent literature that dealt with its objectives. This clearly indicates that smoking prevalence by healthcare workers has not been systematically reported in the literature [

56] and thus identifies a huge gap in research.

Between 1990 and 2024, the prevalence of smoking among health professionals in Australia demonstrated varying declining trends. This review showed that for some of the health professional groups, this decline was in line with the national declining trend for the general (adult) population, while for others, this was not significantly proportionate.

Physicians in the current review were consistently less likely to be current smokers when compared with Australian nurses. However, there were contrasting smoking prevalence rates over the years; for example, the NNHS in 1989–90 showed a current smoking prevalence of 10.2% among Australian physicians [

11]. There were studies, though, conducted around the same time in Australia that showed prevalence rates among physicians between 4% [

33] and 6% [

32]. These findings were consistent with studies conducted earlier, where 17% of US physicians were smoking in the 1980s [

58], but this came down to only 4% by 1994 [

59]. In New Zealand, only 3.4% of the medical staff smoked in 2006; studies conducted in the UK also showed similar consistently low smoking rates [

60]. Smoking prevalence among physicians in the UK, US, and New Zealand has remained consistently lower ever since [

10]. These rates among physicians are a contrast to some of the country rates in recent times like the Philippines (27.8%), Pakistan (29.5%), Turkey (31.6%), Argentina (20.1%), Iran (21.2%), Saudi Arabia (33.8%), and Spain (23.2%) [

10,

56]. A survey conducted in Italy in 2024 showed that 36.9% of the hospital doctors were current smokers [

61]. By 2013, only 7.4% of the specialty-trained doctors were smoking in Australia, although this rate was higher among EDs (10.2%), surgeons (10.7%), or psychiatry (11.0%) VTs [

36]. Unfortunately, we do not have an Australian study after 2013 conducted among physicians that could indicate whether this decline was valid at present. However, it can be assumed that smoking rates among Australian physicians were always lower than that of national adult smoking rates [

62].

The important reasons behind the decline in smoking among physicians in countries including Australia could be attributable to stringent anti-smoking legislatures, tobacco control policies, and practices, including high taxes, plain packaging, and bans on advertisements in print and electronic media, to name a few. The other multifactorial reasons for the vast difference in smoking prevalence among physicians between countries could be due the cultural factors, marketing, lobbying of tobacco companies, and national health policies regarding tobacco control, as well as varying emphasis on the value of smoking cessation during basic medical and continuous professional education between European countries [

63]. Some of the studies documented that an average of one-third of the smoking physicians continued to smoke because they failed to quit in previous quit attempts [

64]. Apart from these factors, occupational stress, which is one of the key factors in addiction [

6], or a country’s culture or wealth might have also influenced the smoking rates [

56]. In countries with a downward trend in smoking among physicians over time, it may also be due to a cohort effect, with younger physicians less likely to start smoking than their older counterparts [

65].

Of all the health professionals, except for AHWs, smoking prevalence among nursing staff in Australia has always been higher than that of physicians or dentists. In the 1970s, almost one in three Australian nurses smoked (32%) [

66,

67]. Over the years, smoking in this group also declined considerably. The highest smoking prevalence, as per this review, was 29.1% among the nurses in 1989–1990 [

11]; since then, the decline continued to 21.3% in 2001 [

11], 18% in 2004–2005 [

11], a rate that persisted in 2011–12 [

47], and then to the lowest prevalence of 10.3% during the 2014–15 period [

53]. To understand this declining trend, the Australian adult smoking rate was 22.4% in 2001, 21.3% in 2004–05, 16.1% in 2011–12, and 14.5% in 2014–15 [

62]; so, nurses were smoking more than adult Australians even until 2011–12. Like in Australia, declining trends among nursing staff were observed in other countries like the USA, Canada, and the UK. In the USA, the introduction of a national program to help nurses quit aided the progressive decline in smoking prevalence amongst nurses from 33.2% in 1976 to 8.4% in 2003 [

46]; a similar decline was also observed in Canada from 32% in 1982 to 12% in 2002 [

68] and in the UK, where it fell from 40% in 1984 to 20% in 1993 [

69]. In New Zealand, the 2006 Census of Population and Dwellings showed midwifery and nursing professionals had a smoking prevalence of 13.6% [

60]; however, this was lower in 2013, when 7.9% of female nurses and 9.2% of male nurses were found to be current smokers [

70]. Before 1999, Japanese nurses had a smoking prevalence between 17.2% and 19.8%, but this came down to 8.2% among registered nurses and 4% among midwives during the 2013–14 period [

71]. There are countries, however, with much higher smoking prevalence burden among nursing professionals like China (46.7% in 2012) [

72] and Italy (36%) [

73]. Like the physician group, we could not identify a more recent study (i.e., conducted in the last 5 years) focusing on Australian nurses to compare their latest smoking rates with those of the current Australian adult smoking rate of 10.7% [

74] or those from around the globe. This would mean, at this juncture, there is insufficient comprehensive data about the smoking patterns of Australian nurses to draw valid conclusions regarding their current smoking status [

44]. Like physicians, the reasons for the smoking decline among nursing professionals in Australia could be attributed to the sustained government tobacco control strategies, such as raising tobacco taxes, advertising bans, mass media public education campaigns, and comprehensive smoke-free environment legislation [

75]. Moreover, the reduction in nurses’ smoking in Australia could be related to the change in nurse education to a tertiary degree, driving higher educational attainment. Across many countries, declining smoking among nurses may additionally mirror the decline in smoking among women as a whole, signifying the changing social norms of smoking among women or reflecting increasing public awareness of the harmful effects of tobacco use [

76].

Dentists in Australia showed consistently lower smoking rates across the years; this overall low rate of tobacco usage, as revealed by this current and other reviews, suggests that dentists have one of the lowest smoking rates among all health professionals, much lower than the general population [

18]. In Australia, this rate varied from 6% in 1994 [

37] to 4% in 2003 [

39] and 2005 [

40]. For American dentists, it was 1% in 1994 [

77] to 6% in 2005 [

78]. Comparable smoking rates were also observed in the UK (5%) in 2010 and in Finland (3%) [

79]. There were some notable exceptions such as in Italy, which showed a rather higher smoking prevalence of 33% among its dentists in 1997 [

80], or 35% in Jordan in 2003 [

81], or in Japan, where 28.9% of dentists were current smokers in the same year [

82]. Apart from these few exceptions, reasons for a generally lower trend of tobacco smoking among dentists may be unclear; it could probably relate to their graphic awareness of the harmful effects tobacco consumption may incur for oral cavities [

18,

83] or be due in part to the incorporation of tougher legislative measures [

83]. As in some countries like Poland, this could also be influenced by the feminization of the dental profession [

84]. Additionally, like physicians, it was observed that dentists in most societies also tend to give up smoking before the general population [

85].

Unlike other health professionals, the decrease in smoking prevalence is very slow among Indigenous people in Australia [

86]. Such a decline was not obvious until recent times [

20,

52]. Historically, AHWs smoked more than the average Indigenous people; Bruce et al. [

20] indicated that 63.6% of AHWs were current smokers in 1995, while 54.5% of Indigenous people were smoking nationally in 1994 [

87]. This was about twice the proportion of Australians overall at that time (males 28%; females 22%) [

88,

89]. There were variable trends in smoking prevalence by AHWs in the subsequent years as well, i.e., 54.8% in 2001 [

48] and 50.6% in 2013 [

50]; these trends were somewhat consistent with national Indigenous male and female smoking prevalences of 52.6% and 47.4%, respectively, in 2008 [

90]. These rates were also similar to the 2006 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS), which showed about 59% of Aboriginal Canadians smoked regularly [

91]; these daily smoking rates were over three times that of all adults in Canada (17%) [

92]. The highest decline among AHWS in Australia was shown by Michelle et al. during a 2021 survey, when 24.6% of AHWs and AHPs were found to be current smokers; this was lower than the 40.2% of Indigenous Australians who were still smoking nationally during 2018–19 [

52].

The failure of a consistent decline among AHWs, until 2021, may be attributed to the high prevalence rate itself, which functions to normalize smoking in this population [

50]. Other factors are stress emitting from racism and family and work expectations [

48,

51]; continually being in a smoking environment; the addictive nature of smoking; suboptimal understanding of nicotine dependence [

49]; socioeconomic variables, including lower levels of perceived social support [

50] or a lack of quitting support [

48,

51]; experiencing negative feelings, including loneliness, depression, or unhappiness [

50]; or, interestingly, patients liking AHWs smoking with them, facilitating connections [

93]. The recent most evidence, however, may augur a wind of change among the broader Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community in Australia that demonstrated successful reductions in smoking rates by promoting smoke-free behaviors [

52]. This also strengthens and validates the continued targeted interventions for at-risk groups.

Smoking is a complex behavior that involves nicotine dependence, often guided by theories of smoking, especially the social cognitive theory or the health belief model, as this is affected by a host of factors related to smokers [

21]. In this review, predictors that were found to be significantly related to higher smoking among health professionals (physicians, nurses, dentists, and AHWs) included age, gender, profession, marital status, smoking in the household/among peers/colleagues, language spoken at home, place of training, area of specialty, and lower emotional wellbeing.

Studies among health professionals have shown that early initiation of cigarette smoking has been associated with greater consumption, longer duration of smoking, and increased nicotine dependence [

94,

95,

96]. Studies by Ann-Maree et al. and Lin et al. from this review showed younger age as a predictor [

43,

53]. The main reasons to have started smoking at an early age may be due to the influence of peer groups and friends, with smoking associated with a ‘high image’ among peers, staying away from families, or living with friends who also smoked [

43]. However, in contrast to early age, older age was also found to be a predictor among nurses for higher smoking [

53]; there are studies, also, where age was not a predictor [

97,

98].

Historical trends have shown gender as a predictor with males smoking more than females generally; this could be related to culture, masculinity, or social norms where peer pressure or self-esteem becomes a priority for the male gender [

99]. Gender was also an important predictor of smoking in this review among nurses [

46,

53] and physicians [

54]; this is corroborated by studies conducted among health professionals in Italy [

97], Saudi Arabia [

100], Armenia [

101], Pakistan [

2], Palestine [

102], and Jordanian male physicians and nurses [

103,

104].

In contrast, there were studies, however, which demonstrated female health professionals with higher smoking rates [

6]; this could be related to professions such as nursing, where predominantly more females are employed. Profession-wise, nurses were more likely to be smokers than physicians [

11]; this finding was consistent with other studies [

4,

10]. Some studies on nurses’ smoking behavior demonstrated that smoking is a coping mechanism against stress, caused by peer behavior and the nursing environment [

10]. Like profession, the specialty of the health professionals (like trainee psychiatrists smoking more than trainee physicians or trainee general practitioners) [

32,

46] was substantiated by studies that showed trainee psychiatrists [

5,

32], psychiatry residents [

5,

32], nurses, respiratory physicians, and occupational therapists smoking more than physicians or other categories of health professionals [

4]. This was also evident in a few other studies [

5,

105], where surgeons or health professionals working in operating rooms or ICUs were shown to be likely smokers [

104]. The reasons for these observations are not clear but could be attributable to stress, personal characteristics, and/or professional role conflicts [

106].

Being single or separated/divorced, parental smoking, or living with a smoking partner or siblings were also identified as predictors [

46]; these were consistent with studies conducted elsewhere [

102] that showed higher smoking among close friends and colleagues [

2,

51] or where there was a positive family history of smoking [

102].

Where health professionals received their training was also recognized as a predictor with hospital-trained nurses more likely to smoke than university-trained nurses [

42]; similar findings were observed elsewhere where physicians and nurses from public health institutes and general hospitals [

107] or health professionals from public hospitals were smoking more than private hospitals. This could be attributed to stricter anti-tobacco policies or their implementation as such in private institutions [

2].

Rural residents are likely to smoke more due to certain demographic characteristics, such as low income, low educational attainment, and lack of health coverage [

4]. However, rural vs. urban residence was found not to be a predictor in this review, as was consistent with some studies in the USA [

4] and elsewhere [

102].

Limitations of the Review

There were some limitations to this scoping review process. There could be potential inherent publication or selection bias due to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This review only considered articles that were published, as well as articles written in English only—essentially exposing this review to publication and selection bias. A majority of the included studies were also cross-sectional and anonymous, and only a few longitudinal data sets (among health professionals) were available and hence were subjected to self-reporting; this might mean more non-smokers completed the questionnaires, resulting in underestimation and underreporting of the prevalence in some of the studies. So, when we are observing a strong declining trend in smoking rates in Australia, one must take into account the potential data biases (i.e., the impact of self-reported biases) to balance the interpretation. Also, by nature, a cross-sectional design is unlikely to capture change in smoking behavior, since smoking behavior is measured only at one point in time, so such a study will yield heterogeneity among smokers who belong to the same stage of smoking [

108]. There was also a lack of statistical testing for trends and predictors in many of the reviewed studies. The geographical and temporal representation of the included studies in this review was also a challenge.

One factor across most of the studies, however, was a lack of standardization regarding the definition of ‘current smoking’. Methodological sources of discrepancy due to differences in survey questions used to define current smoking are nothing new in research though [

109]. Nearly half of the studies did not mention a consistent definition of ‘current smoking’, which may affect the reliability of aggregated findings [

108]. Most studies often use different definitions of smoking, which has often made it difficult to compare findings across studies. The variations in definitions include the number of cigarettes/pipes/cigars smoked per day, the number of days smoked per week or month, or the amount of lifetime cigarette use; all have served as a proxy for smoking prevalence. For example, in the US, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) limits its question about current smoking to respondents who reported smoking ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime; however, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) does not designate a cut-point for number of lifetime cigarettes smoked [

109]. This invites potential discrepancies across the two data sets. There are other implications for both the self-reporting nature of the studies included in this review and the varying definitions of current smoking. These may potentially indicate that there has been an underestimation of smoking prevalence among healthcare workers or that the accuracy of the smoking trends of Australian healthcare workers is compromised and any comparisons made need to be interpreted with caution.

A majority of the studies also did not provide gender-specific prevalence rates, and not all the studies discussed predictors of smoking as such. A smaller sample size, acceptable margin of standard error, and varying response rates could also add complexity in terms of the generalizability of the findings across some Australian states or the country as a whole.