1. Introduction

Observations with a Large Area Telescope (LAT) of the

Fermi satellite revealed that the extragalactic

-ray sky is dominated by blazars, i.e., radio-loud active galactic nuclei (AGN) whose jets are directed at a small angle to the line of sight [

1]. According to the reclassification [

2] of the second data release of the fourth

Fermi–LAT catalog [

3],

of the 2980

-ray-emitting AGN (outside of the Galactic Plane, with galactic latitudes

) are blazars. The remaining sources are associated with other AGN types, e.g., misaligned AGN (including radio galaxies) and narrow-line Seyfert 1 (NLS1) galaxies. NLS1 galaxies were the third AGN type, after BL Lac objects and flat-spectrum radio quasars (FSRQs), that were recognised to be able to produce

-ray emission [

4]. There are 24

-ray-emitting NLS1 galaxies and a few ambiguous or intermediate cases reported in [

2]. Apart from those, additional

-ray emitter sources are connected to NLS1 galaxies in the literature, such as 4C+04.42 [

5,

6], 4FGL J0117.9+1430 [

7], 3FGL J0031.6+0938 [

8], and J164100.10+345452.7 [

5,

9].

NLS1 galaxies are characterised by narrow permitted emission lines (with a full width at half-maximum, FWHM(H

)

,

10]), strong Fe

ii multiplets, and weak O

[iii] emission [

11]. Most of the NLS1s are radio-quiet, as only ∼7% of them show radio emission [

12,

13]. Radio studies accomplished at kpc-scale resolutions showed diverse radio morphologies of NLS1 sources and, combined with multiwavelength data, revealed that the radio emission may originate from the AGN and/or the star formation in the host galaxy [

14].

On the other hand, the extremely radio-loud NLS1s (∼2.5%) show blazar-like characteristics: flat radio spectrum, compact cores on milliarcsecond (mas) scale, high brightness temperatures, and significant variability, see, e.g., [

15]. In the Monitoring of Jets in Active Galactic Nuclei with Very Long Baseline Array Experiments (MOJAVE) program, three of the five monitored

-ray-loud NLS1 sources also showed apparent superluminal jet component motions [

16]. It was shown that radio-loud NLS1s with blazar-like characteristics often experience enhanced variability in the infrared, a significant fraction also on intra-day timescales, indicating that at least part of the infrared emission in these objects originates from the boosted synchrotron jet [

17,

18,

19]. Short-timescale variability was also reported in the optical band (intra-night optical variability) and was also predominantly measured in

-ray-emitting, jetted NLS1s, implying the relativistically boosted jet as the origin of the optical variability (e.g., [

20,

21]). Concerning the higher-energy regime, enhanced X-ray variability in relatively radio-fainter (mildly radio-loud) NLS1 sources, in comparison to regular Seyfert galaxies, may also indicate that they harbour jets contributing to their radio emission [

22,

23,

24]. On the other hand, the rapid X-ray variability of the

-ray-emitting NLS1, 1H0323+342, has been attributed to its accretion disk [

25].

NLS1 galaxies are thought to contain a low-mass (<10

8 M

⊙) supermassive black hole in their central engine and/or are often considered to be at an earlier evolutionary stage [

12,

26]. In that context, radio-bright NLS1s showing blazar-like characteristics can be the low-mass counterparts of FSRQs [

27]. An alternative scenario explains the narrowness of the permitted spectral lines by a broad line region with special (flattened) geometry [

28].

In the

Fermi–LAT Fourth Source Catalog (4FGL) [

3], the

-ray-emitting object 4FGL 0959.6+4606 was associated with the radio galaxy 2MASX J09591976+4603515 (hereafter 2MASX J0959+4603) at a redshift of

[

29]. However, another probable radio-emitting counterpart, SDSS J095909.51+460014.3 (hereafter SDSS J0959+4600), an NLS1 galaxy at

[

30], was reported later by [

31]. According to [

17], the radio-loudness factor of SDSS J0959+4600 (1000) is two orders of magnitude larger compared to that of 2MASX J0959+4603 (20). Both radio sources are within the 95% confidence level

-ray localisation uncertainty region if all

Fermi–LAT data are considered. However, if the 15-month data are used when 4FGL 0959.6+4606 shows a high

-ray state, then only SDSS J0959+4600 falls into the localisation radius. Additionally, SDSS J0959+4600 showed

mag brightening in infrared bands coincident in time with the

-ray brightening, and its spectral energy distribution (SED) could be well described with a single-zone homogeneous leptonic jet model. Thus, its multi-band characteristics were similar to the other known

-ray-emitting NLS1 galaxies [

31].

Since

-rays in AGN are known to be produced in relativistic plasma jets expelled from the vicinity of the central supermassive black hole, and because the high-resolution technique of very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) is the only method suitable for directly imaging the synchrotron radio emission of milliarcsecond (mas)-scale compact jets, we initiated observation of both proposed counterparts of 4FGL 0959.6+4606 with the European VLBI Network (EVN). This way, we were able look for possible jets, compact radio-emitting features in them, and signatures of relativistic beaming effects.

Section 2 below describes the observation and data analysis.

Section 3 presents the results. We discuss our findings in

Section 4 and conclude the paper in

Section 5.

Assuming a

Cold Dark Matter cosmological model with a Hubble constant of

km s

−1 Mpc

−1 and density parameters of

and

(the approximate values of the ones derived from the European Space Agency Planck satellite mission data [

32]), 1 mas angular size corresponds to

kpc projected linear size at the redshift of J0959+4600 [

33].

2. Observation and Data Reduction

Our EVN observation was conducted on 28 May 2023 at 5 GHz frequency, with a bandwidth of 256 MHz divided into eight intermediate frequency bands (IFs), each containing 64 channels. The following antennas participated and provided useful data: Effelsberg (Germany), Tianma (China), Jodrell Bank Mark 2 (United Kingdom), Westerbork (The Netherlands), Medicina (Italy), Onsala (Sweden), Toruń (Poland), Yebes (Spain), and Irbene (Latvia). Westerbork only recorded data in the four IFs at the upper half of the band.

The observation lasted for 3 h and was carried out in phase-reference mode [

34]. In that mode, the visibility phases are corrected using the measurements of a bright and compact calibrator source located at small angular separation from the target, and the obtained phase solutions are transferred to the target source(s). In our experiment, the phase-calibrator source was ICRF J095819.6 + 472507, located at

angular separation from the target field. Its coordinates according to the latest, third realisation of the International Celestial Reference Frame (ICRF3) [

35] are right ascension

mas and declination

mas (note: data obtained from

https://hpiers.obspm.fr/icrs-pc/newwww/icrf/icrf3sx.txt, accessed on 2 February 2025).

The angular separation of the two proposed counterparts is ∼2.5′, comparable to the half-power beam width of the largest-diameter antennas of the array, Effelsberg (∼2.4′) and Tianma (∼3.7′), at this observing frequency. For all other antennas, both targets fall well within their primary beams. Therefore, we asked for multi-phase-centre correlation at the SFXC correlator of the Joint Institute for VLBI European Research Infrastructure Consortium [

36]. During the experiment, all antennas except for Effelsberg and Tianma observed the midpoint between the two proposed counterparts, while Effelsberg and Tianma were performing nodding-style phase referencing for both individual target sources. In summary, the phase-calibrator source and the target field were observed alternately by spending ∼1.3 min on the calibrator and ∼3.5 min on the target field by most of the antennas, while Effelsberg and Tianma observed 2MASX J0959+4603 and SDSS J0959+4600 alternately during the target-field scans. That way, the smaller antennas had longer on-source times on the targets than the two largest antennas. The on-source time for both sources was ∼1.9 h.

The VLBI visibility data were reduced following the standard steps in the Astronomical Image Processing System (

aips, [

37]). These included the a priori amplitude calibration, ionospheric, parallactic angle, and instrumental delay corrections. Afterwards, fringe-fitting was performed on the phase-reference source, and four-four channels were removed for all sources from the beginning and the end of each IF, to avoid the lower amplitude values at the edges of the IFs. Then, the calibrated data of the phase-reference source were exported and imaged in the

Difmap program [

38]. During the hybrid mapping process, several iterations of

clean deconvolution [

39] and phase self-calibration were performed. Then, the antenna-based amplitude correction factors were determined. These were generally below

, except for the second IF of Tianma. The amplitude corrections exceeding 5% were applied to all visibility data in

aips, and a second fringe-fit was performed for the phase-reference calibrator, taking into account its structure recovered in the hybrid imaging. These solutions were interpolated and applied for the two target sources. Then, their data were exported to

Difmap for imaging. SDSS J0959+4600 turned out to be bright enough that we were able to perform fringe-fitting

aips on this target source, as well.

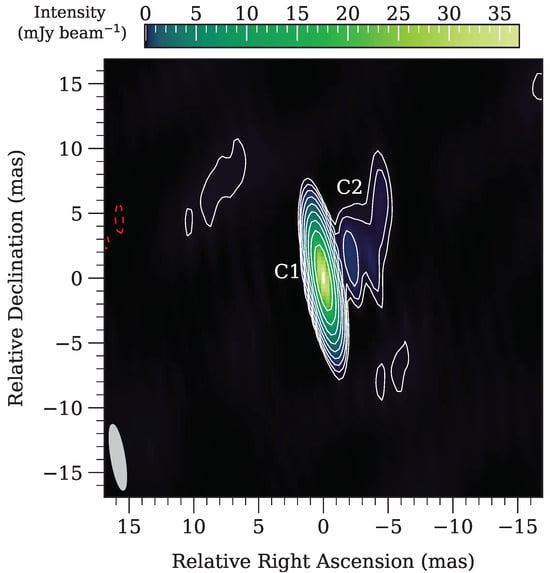

4. Discussion

The most accurate optical position of the NLS1 galaxy is provided in the latest, third Data Release (DR3) [

47] of the

Gaia space telescope [

48],

mas and

mas. The VLBI and

Gaia right ascensions agree within the errors. Formally, the optical declination is slightly to the north compared to the VLBI position. However, their

mas positional difference is comparable to the combined uncertainty of the optical and VLBI declinations,

mas. Therefore, we conclude that there is no significant difference between the

Gaia optical and the radio interferometric positions of the brightest component of SDSS J0959+4600. Thus, we can safely assume that component C1 is the radio core of the NLS1 galaxy, and C2 is a jet component. Similar pc-scale core–jet structures have been seen in other

-ray-emitting NLS1s (e.g., [

15,

16,

24] and references therein).

The brightness temperature of a Gaussian component can be calculated as, e.g., [

49]:

where S is the flux density in Jy, the observing frequency in GHz, the component size (FWHM) in mas, and z the redshift. In the case of SDSS J0959+4600, K. This value exceeds the equipartition brightness temperature limit, K [50], indicating mild relativistic boosting in the source with a Doppler factor of . This Doppler factor is much lower than the one assumed by [31] () to fit the SED of SDSS J0959+4600. However, they modelled the high -ray flux state of the source, which occurred around September 2017, while our EVN observation took place 6 years later.

While 2MASX J0959+4603 was not detected in our 5-GHz VLBI observation, both objects have detections at GHz frequencies at lower resolutions: at

GHz in the Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty centimeters survey (FIRST, [

51]) and at 3 GHz in the more recent Very Large Array Sky Survey (VLASS, [

52]). They appear as unresolved sources in both surveys; their flux densities are given in

Table 2. The flux density values of the first two VLASS epochs were obtained from the Quick Look catalogs (version 3 for the first epoch and version 2 for the second epoch) downloaded from the Canadian Astronomy Data Centre (CADC) (note:

https://www.cadc-ccda.hia-iha.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/en/vlass/, accessed on 2 February 2025). For SDSS J0959+4600, two objects were listed in both epochs. Following the CIRADA: VLASS Catalog User Guide (note:

https://ws.cadc-ccda.hia-iha.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/files/vault/cirada/tutorials/CIRADA__VLASS_catalogue_documentation_2023_june.pdf, accessed on 2 February 2025), we used the one with duplicate flag value 1. For the third VLASS epoch, for which no catalog has been produced yet, we downloaded the cutouts of the quick-look images from the CADC and fitted them using the

aips task

imfit. The integrated flux density values obtained by the fitting were increased by

since, according to the CIRADA: VLASS Catalog User Guide, the flux densities are underestimated by this amount. Since SDSS J0959+4600 appeared on two cutouts, we took the average of the two fitted flux densities.

Apart from the last VLASS epoch, flux density values were reported by [

31]. However, they used different software to fit the images, and they may not have had access to the reprocessed first-epoch data at that time. With the exception of the first-epoch VLASS flux density of SDSS J0959+4600, we obtained similar values for both sources; thus, we can confirm that 2MASX J0959+4603 did not show variability at 3 GHz. On the other hand, the flux density of SDSS J0959+4600 decreased significantly between the first two VLASS epochs.

We calculated the power-law spectral index

(defined as

, where

is the frequency) for 2MASX J0959+4603 between

GHz and 3 GHz using the average of the VLASS flux densities. The obtained spectrum is steep, with

. Using this for extrapolation, we would expect a total flux density of ∼1.6 mJy at 5 GHz for 2MASX J0959+4603. This should be easily detected in our EVN experiment if it is contained in a mas-scale compact feature. In turn, its non-detection implies that the size of the radio-emitting region in 2MASX J0959+4603 exceeds the largest recoverable size of our observation, ∼50 mas. The origin of this radio emission is not clear. It can be created in the extended lobe of the AGN or arise from star formation in the host galaxy, or it can be the result of the combination of both processes. If we assume that the

-GHz flux density of 2MASX J0959+4603 solely arises from star formation, its radio power, ∼2.4

W Hz

−1, would imply a star formation rate of ∼130 M

⊙ yr

−1 [

53]. However, its infrared colors measured by the

WISE satellite put it into the AGN locus of the infrared color–color diagram instead of the starburst region [

54].

For SDSS J0959+4600, the FIRST and first-epoch VLASS flux density values imply a rather inverted spectrum. However, due to the apparent flux density variability, the specific spectral index value may be misleading in that case, because the observing epochs are different. Nevertheless, accepting it at face value, an inverted radio spectrum would be consistent with a blazar-like, beamed NLS1 object. Assuming that we did not lose significant flux density in our VLBI measurement due to an extended structure resolved out at the long baselines, and disregarding possible source variability, we could also calculate the spectral index of SDSS J0959+4600 between 3 GHz and 5 GHz. For that, we used the last VLASS epoch, the one closest to our EVN observation. The obtained implies that the radio spectrum is flat between these frequencies.

5. Conclusions

The

-ray source 4FGL 0959.6+4606 was originally associated with a radio galaxy [

3]. However, ref. [

31] showed that an extremely radio-loud NLS1 galaxy is a more probable counterpart of the high-energy source. To help resolve this issue using high-resolution radio imaging, we performed 5 GHz VLBI observation of both sources with the EVN in 2023. Among the two candidate counterparts of the

-ray source, the NLS1 SDSS J0959+4600 was clearly detected with a bright mas-scale compact core and a fainter jet feature. The brightness temperature of the core exceeds the equipartition limit, indicating moderate Doppler boosting. On the other hand, we did not convincingly detect any mas-scale compact radio feature in the radio galaxy 2MASX J0959+4603, indicating that its total radio emission originates from spatially extended features and not the core of an AGN. Our results lend strong support to the suggestion of [

31] that the radio-bright NLS1 object is the most probable source of the

-ray emission in 4FGL 0959.6+4606.

Our finding highlights the significance of high-resolution radio observations in the identification of

-ray-emitting objects (see also [

55]). It can be quite important when the different proposed counterparts belong to source groups represented in relatively small numbers among the known

-ray emitters. Thus, like in the case of 4FGL 0959.6+460, the proposed counterparts, a radio galaxy and an NLS1 object, both can have essential but different implications for the possible

-ray emission mechanisms. Our findings and the growing number of other known

-ray-emitting NLS1 objects confirm that contrary to previous beliefs, these unique objects are not only capable of but are proficient in launching powerful jets similar to blazars.