1. Introduction

Metropolitan areas serve as the fundamental units of international competition and the primary platforms for a nation’s economic and social development, playing a pivotal role in driving integrated regional development [

1]. Defined as urbanized spatial systems anchored by megacities or large urban hubs with extensive radiating influence, metropolitan areas typically span a one-hour commuting radius as their functional footprint [

2]. These regions integrate diverse cities of varying characteristics, scales, and hierarchies within geographically contiguous zones, underpinned by shared ecological and infrastructural foundations [

3]. In China, rapid economic growth, the continuous expansion of industrial scale, and the increasingly sophisticated industrial system have effectively propelled the construction and development of metropolitan areas [

4]. Emphasizing the development of modern service industries, with tourism as a key component, is essential for metropolitan areas to accelerate the transformation of economic development modes, establish a modern industrial system, and cultivate new economic growth poles [

5]. Currently, the Chinese government has approved the construction of seven metropolitan areas: Nanjing, Fuzhou, Chengdu, Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan, Xi’an, Chongqing, and Wuhan. These areas are endowed with abundant natural landscapes, historical and cultural tourism resources, and host numerous high-level tourist attractions, making them significant tourist destinations in China.

The rapid urbanization of metropolitan areas globally has intensified the need for sustainable spatial planning, particularly in balancing economic growth with environmental stewardship. The spatial organization of tourism within metropolitan systems represents a critical research frontier in regional planning [

6]. The tourism spatial structure refers to the spatial organizational relationships among various elements of the tourism system, including their positions, interconnections, and interactions in space, as well as their generation, movement, and development [

7]. Researchers primarily investigate the evolutionary processes, spatial structures, and formation mechanisms of tourism from a spatial perspective, uncovering the characteristic patterns and typical models of tourism space formation and evolution [

8,

9]. Initially, research on the spatial structure of tourism in metropolitan areas focused on individual cities, emphasizing the spatial layout, network structure, and evolutionary patterns of tourism within single cities, particularly from perspectives such as the allocation of tourism development elements and the spatial mobility of tourists [

10,

11]. With the rapid development of global cities, metropolitan areas such as New York, Tokyo, and Shanghai have emerged as key regions for global urban development due to their advantages in capital, technology, and talent [

12]. Consequently, research on metropolitan tourism has expanded from individual cities to broader metropolitan regions. As urban tourism evolves into metropolitan tourism, various elements gradually converge, tourism formats continually evolve, and spatial relationships become increasingly complex [

13]. Scott categorized the evolution of metropolitan tourism spatial structures into three stages: single-center, multi-center, and networked stages [

14]. He argued that during the multi-center and networked stages, the connections and functional cooperation among centers become more pronounced. Huang suggested that the spatial effects dominated by the networked model would gradually strengthen, contributing to the formation of a balanced and open regional space [

15]. Furthermore, metropolitan areas nowadays face dual challenges: leveraging tourism for economic transformation while mitigating urban sprawl and environmental degradation. Existing studies often neglect the integration of multi-source geospatial data to address these sustainability challenges, limiting their applicability in dynamic governance contexts. Therefore, studying tourism’s spatial structure and its associated aggregation in metropolitan areas is crucial for optimizing the spatial structure of tourism, promoting its progression toward the multi-center networked stage, and facilitating coordinated regional development. Current research on the spatial structure of tourism in metropolitan areas encompasses the current status and optimization, evolution and influencing factors, optimization strategies, as well as spatial effects of tourism, spatial tourism behaviors, the spatial differential development of tourism, and the spatial layout of the tourism industry [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Nighttime light (NTL) data and point of interest (POI) data are invaluable for studying urban spaces [

21]. These datasets are frequently employed to analyze urban patterns and urbanization, human activities and their impacts, and regional economic growth; quantify regional GDP changes and population spatialization; and estimate electricity and energy consumption [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. NTL data are characterized by open data sources, rapid updates, extensive coverage, and high temporal resolution, making them widely applicable in fields such as metropolitan area expansion, urban economic and industrial development, urban evolution, and the hierarchical patterns of urban systems [

27,

28]. With the explosive growth of big data, not only statistical data but also remotely sensed images and other openly accessible data are playing an increasingly significant role in research on urban structure [

29]. Large-scale, high-precision positioning data enable scholars to analyze the internal spatial structure of cities from micro, macro, dynamic, and static perspectives [

30]. POI data, which contain information about the spatial distribution and types of geographical features, offer advantages such as precise feature positioning, diverse feature types, and rapid data updates, representing point data of geographical entities on the ground [

25,

31]. Compared to traditional survey methods, POI data provide highly accurate and timely identification of urban centers. Currently, POI data are primarily used for urban boundary extraction, urban built-up area identification, urban functional area classification, and urban industrial spatial pattern analysis [

32].

In recent years, research on NTL data and POI data has extended into the field of tourism research, primarily focusing on reflecting changes in urban leisure hotspots, the impact of tourism activities, and tourism spatial spillover effects [

33]. However, few studies have combined NTL data and POI data to examine the spatial structure of tourism in metropolitan areas. Despite growing interdisciplinary applications, three fundamental barriers have hindered the widespread adoption of the integration of two datasets in tourism research. Firstly, the daily update frequency of POI data (e.g., Amap/Baidu Map) contrasts sharply with the monthly composite cycles of NPP-VIIRS NTL data, creating synchronization challenges for dynamic studies [

25]. Secondly, POI data capture tourism facility distribution and NTL data reflect economic activity intensity; existing studies often fail to establish interpretable linkages between tourism-related POI categories and NTL luminosity gradients. Thirdly, conventional zonal statistics methods tend to overlook the modifiable areal unit problem when correlating POI density with NTL intensity, particularly in the transitional urban–rural fringe.

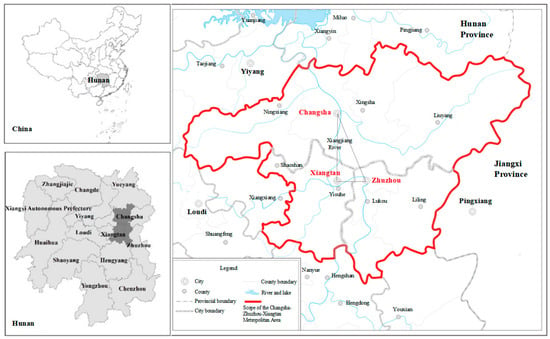

In order to address the above limitations, the paper extracts the potential central range through multi-scale segmentation of NTL intensity and combines it with tourism POI data to identify the multi-center distribution in the Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan Metropolitan Area (CZTMA) of China. As the only approved metropolitan area in central China, CZTMA exhibits transitional characteristics between single-core dominance (Changsha) and emerging polycentricity (Zhuzhou–Xiangtan), providing an ideal laboratory for observing metropolitan spatial restructuring. Furthermore, the area encompasses gradient urbanization zones from the urban core to the ecological preserves, enabling comprehensive analysis of correlations between the tourism industry and light intensity across development spectra. Based on tourism POI data and NTL data, the paper analyzes the tourism spatial structure of CZTMA from multiple perspectives, including functional structure identification, spatial correlation measurement, and the service range of the main center, aiming to provide insights for optimizing the tourism spatial planning of CZTMA and aligning with global sustainability agendas by demonstrating how spatially informed policies can enhance tourism’s contribution to green economies, resilient infrastructure, and inclusive growth.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Tourism POI Kernel Density and NTL Intensity

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the spatial distribution of tourism points of interest (POIs) generally exhibits a trend of gradual decline from the urban core to the surrounding suburbs. Three high-value areas are identified: the central urban area of Changsha (encompassing Furong District, Yuelu District, and Yuhua District), Yuetang District in Xiangtan, and Hetang District and Tianyuan District in Zhuzhou. The high-value kernel density area in Changsha covers a relatively large expanse, radiating outward continuously, with the primary direction of expansion toward the intersection of Changsha, Zhuzhou, and Xiangtan. The high-value areas in Zhuzhou and Xiangtan are symmetrically distributed along the left and right banks of the Xiangjiang River. These regions, though smaller in extent, radiate outward to surrounding districts and counties. Additionally, the relatively peripheral areas of the Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan metropolitan region, such as Ningxiang, Liuyang, Liling, Lukou, and Yisuhe, feature sporadic medium-value kernel density points, displaying a multi-point, intermittent distribution. This pattern forms an overall spatial configuration characterized by “dense in the center and sparse on the periphery”.

When the hexagonal grid is overlaid with processed NTL data, the results are shown in

Figure 4. The distribution trends of NTL intensity values and tourism POI kernel density values are similar, both exhibiting a radiating pattern from the urban core to the suburbs, with values gradually decreasing. While the three high-value areas remain consistent, the NTL data generate more continuous, centrally clustered regions. The number of high-value centers in Changsha increases, and their surrounding radiation range expands. In Xiangtan and Zhuzhou, the continuous medium- and low-value areas also grow larger. All three high-value areas exhibit a tendency to converge toward the intersection of Changsha, Zhuzhou, and Xiangtan.

From a local perspective, the high-value centers of tourism POI kernel density are distributed in a multi-point, intermittent manner, whereas the high-value centers of NTL intensity are distributed in a continuous, clustered pattern, demonstrating a point-to-block-to-cluster diffusion. In the marginal areas of the metropolitan region, the POI kernel density forms sporadic high-value centers, while the NTL intensity is characterized by large-scale, low-value continuous areas, accompanied by a small number of marginal low-value centers.

3.2. Overall Spatial Distribution of the Coupling Between Tourism POI and NTL

The two types of gridded data were normalized using ArcGIS 10.8 software. Employing the standard-deviation classification method, 1.5 times the standard deviation of the normal distribution was used as the classification criterion. To align with the two-factor mapping method, the data were divided into three levels: high, medium, and low (

Table 2). The Thiessen polygon fishnet data were linked to the NTL data and the POI kernel density data, and the coupling between the two datasets was analyzed using the symbol-counting statistical method.

As shown in

Figure 5, the spatial coupling between tourism POI kernel density and NTL data demonstrates a high degree of spatial coordination. The proportion of hexagonal grids with matching coupling relationships relative to the total number of grids in the study area reached 86.77%. Among these, 495 hexagonal grids exhibited a high–high coupling relationship, 56 grids show a medium–medium coupling relationship, and 16,434 grids display a low–low coupling relationship. Areas with matching coupling relationships generally form a ring-like structure, radiating outward from the intersection of Changsha, Zhuzhou, and Xiangtan. The high–high coupling areas of the two datasets are primarily concentrated along both sides of the Xiangjiang River and in the main urban areas of Changsha–Zhuzhou–Xiangtan. Point-like distributions are also observed in the main urban areas of Ningxiang, Liuyang, and Liling. These regions exhibit high levels of economic development and abundant tourism resources, resulting in elevated POI and NTL values. The medium–medium coupling areas are distributed around the high–high coupling zones, primarily representing transitional areas between urban and suburban regions. The low–low coupling areas are located in suburban and rural areas surrounding the city.

3.3. NTL Value Higher than Tourism POI Kernel Density Value

Areas where NTL values exceed tourism POI kernel density values (high–medium coupling, high–low coupling, and medium–low coupling relationships) are primarily distributed outside the high–high and medium–medium coupling zones, forming a ring-like pattern (

Figure 6). The high–medium coupling areas are located outside the high–high coupling zones, while the medium–low coupling areas are situated outside the medium–medium coupling zones, mainly in transitional areas between the city center and surrounding villages and towns. Due to their proximity to the city center, and given the saturation of commercial points in the urban core and convenient transportation networks, the number of POIs decreases gradually from the city center outward. However, the light brightness value does not decline significantly due to the light spillover effect. Consequently, the POI value decreases more sharply relative to the light value, resulting in a general trend of declining light values from high to low and forming high–medium coupling areas.

The high–low coupling areas are found in regions with high light values but few tourism POIs, such as residential areas, industrial parks, government agencies, airports, and other areas with extensive building coverage. Examples include the Sany Heavy Industry Industrial Park and Huanghua International Airport in Xingsha, as well as the government office area in Tianyuan District, Zhuzhou. These areas lack significant tourism POI entities, resulting in NTL values that far exceed POI values.

The medium–low coupling areas are predominantly located in suburban regions, far from the city center. These areas are typically characterized by factories, transportation facilities, and logistics industries, which are associated with low land prices and minimal pollution. For instance, the Shifeng District Industrial Park in Zhuzhou hosts a large number of factories and affiliated institutions, driving the development of transportation and logistics industries and ultimately forming medium–low coupling areas.

3.4. NTL Value Lower than Tourism POI Kernel Density Value

Areas where NTL values are lower than tourism POI kernel density values are less common. Overall, medium–high and low–medium coupling areas dominate, while low–high coupling areas are rare. As shown in

Figure 7, the high population density in the central urban area results in tourism POI density exceeding the light threshold, forming medium–high coupling areas. Examples include Wuyi Avenue in Changsha, Jianshe South Road in Zhuzhou, and Shaoshan Road in Xiangtan. The low–medium coupling areas are sparsely distributed in the main urban area and are primarily found in less-developed fringe areas, as well as urban parks or green spaces transitioning from the city center to the suburbs. Examples include Xiangfu Cultural Park in Changsha, Tianma Mountain Park, Yuhu Park in Xiangtan, and Shaofeng Park in Shaoshan.

3.5. Correlation Between Different Types of Tourism Spaces and NTL Values

The closer the Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) bandwidth is to the global scale, the greater the influence of the explanatory variable on NTL brightness at a broader or global scale [

44]. Conversely, a smaller bandwidth indicates that the explanatory variable affects the average brightness value locally or within a smaller range. Based on the calculations from Model (2), the MGWR bandwidth ranges between 69 and 1993, indicating significant variation in the scale of influence (

Table 3).

The distribution factor of shopping spaces has a negligible and negative correlation. The coefficient values range from −0.074 to −0.072, with an average of −0.074. The coefficient exhibits a gradual decline from the center to the periphery of the study area, with the negative impact intensifying outward. The distribution factor of accommodation spaces shows a positive but insignificant correlation. The coefficient values range from 0.064 to 0.067, with an average of 0.066, displaying a circular-layered decline from the center to the periphery. The MGWR regression results for shopping, catering, and entertainment factors approximate the global bandwidth, indicating local characteristics. Although some spatial variation exists, the changes are not significant, and the coefficients remain relatively stable across space. The distribution factor of transportation spaces is positively correlated with NTL brightness. The regression coefficient values range from 0.193 to 1.406, with an average of 0.534. In terms of absolute value, its impact is moderate. The number of transportation POIs in the grid is fixed, and the rate of decline in NTL intensity from the city center to the periphery is less pronounced than that of transportation POIs, generally showing an increasing trend from the center outward. The regression coefficient for the distribution factor of sightseeing spaces transitions from positive to negative, moving from multiple high-value centers to the periphery. The coefficient values range from −0.977 to 2.866, with an average of 0.082. In absolute terms, its impact is the most significant. The results suggest that, within a localized range, sightseeing spaces exert a substantial influence on NTL brightness, with notable spatial heterogeneity.

4. Discussion

By gridding and normalizing the POI and NTL data of CZTMA and conducting a coupling analysis, this study explores the characteristics of the spatial structure of tourism within the region. The findings provide a critical decision-making framework for sustainable urban tourism development by revealing the spatial interaction mechanisms, serving as an early warning system for detecting unsustainable expansion patterns.

4.1. Refined Identification of Tourism Development Centers

Compared to existing studies based on statistical data, this paper overcomes the limitations of administrative units by utilizing NTL data combined with tourism POI data. This approach identifies the main centers of tourism development in CZTMA at a more refined scale. Additionally, it analyzes the characteristics of the spatial structure of tourism from multiple perspectives, including the functional structure of the main centers, spatial correlation measurement, and the service range of these centers.

The results reveal that tourism development in CZTMA is concentrated in the central region, with weaker development in the eastern and western parts. The intersection area of the three cities shows a clear trend of enhancement, indicating overall unbalanced development. The kernel density of tourism POIs in marginal areas such as Ningxiang, Liuyang, Liling, and Yisuhe are nearly zero, suggesting that the tourism industry in these areas is not dominant and requires the driving force of strong tourism attractions. Notably, high–high spatial coupling zones account for 2.52% of the total study area, exceeding the values reported in the Shanghai, Fuzhou, and Changchun metropolitan areas [

15,

44]. This disparity highlights intensified spatial polarization within central China’s newly metropolitan areas, potentially attributable to asymmetric resource allocation mechanisms under regional development policies. In the future, the tourism industry of CZTMA should aim to balance regional development, further optimize the spatial layout of tourism, strengthen Changsha’s leading role, leverage the comparative advantages of Zhuzhou and Xiangtan, and jointly build a tourism spatial pattern characterized by complementary strengths and high-quality development. More specifically, the local government could establish a tourism development fund allocating some of Changsha’s tourism revenue to subsidize infrastructure in peripheral counties (such as Ningxiang and Liuyang), following the EU’s structural fund model for regional cohesion [

13]. Consequently, policymakers can stimulate job creation, diversify local economies, and reduce migration pressures on urban centers—key tenets of SDG 8. Furthermore, a cross-city tourism commission with authority should be created in order to coordinate attraction ticket pricing, transportation links, and marketing budgets across municipal boundaries, addressing current fragmentation issues.

4.2. Effectiveness of the Combined POI and NTL Data Method

This study validates the effectiveness of the method combining POI data and NTL remote sensing data for identifying the tourism spatial structure of metropolitan areas. This approach provides a new perspective for evaluating urban tourism development. Unlike single NTL data, POI data incorporate characteristics related to metropolitan boundaries, such as the relationship between regional scale and human activities, offering a more comprehensive representation of tourism’s spatial structures.

The high–high coupling areas are primarily distributed in the centers of three cities and extend to the urban periphery, consistent with previous studies on CZTMA [

45]. Compared to the single-center model dominant in European metropolitan areas [

11], the multi-center identification better captures the transitional spatiality of Chinese urban agglomerations. The intersection area of the three cities is surrounded by three high–high coupling zones (

Figure 8). In the future, this area should be designated as the metropolitan’s “Urban Central Park”, capitalizing on the Xiangjiang River’s hydrological network, surrounding mountain ranges, and arterial transportation corridors. Development priorities must emphasize establishing interconnected nature reserves, suburban park clusters, urban green spaces, and multi-functional greenway systems to create an integrated ecological matrix. Through protective development, local governments could promote green industries such as scientific and technological innovation, creative design, health and wellness, and sports. This would create several green ecological corridors extending to surrounding counties and cities, establishing the urban green heart and ecological security barrier of the metropolitan area. This approach not only preserves biodiversity but also aligns with SDG 11’s emphasis on sustainable urban ecosystems.

4.3. Spatial Distribution Coupling Heterogeneity

In terms of spatial distribution coupling heterogeneity, medium–high and low–medium coupling areas are mainly distributed in high-density residential areas, industrial parks, government office zones, and less-developed suburban regions. These areas could benefit from the planning of more outdoor recreational spaces, such as urban green spaces, neighborhood parks, and special-themed gardens. These spaces would not only serve as excellent venues for citizens to travel and relax but would also play a crucial role in the urban ecosystem by mitigating the urban heat island effect. Consequently, the local government could implement effective measures to increase POI density in these zones, such as mandating the provision of visitor service centers within specific scope, enforcing park-green space coverage requirements, and requiring new residential developments to allocate some land area for cultural-tourism facilities.

Meanwhile, those areas where the tourism POI kernel density value exceeds the NTL intensity value are primarily located in characteristic small towns such as Huaminglou Town, Daweishan Town, Huitang Town, and Yisuhe Town. These areas are rich in tourism resources and feature numerous scenic spots. However, inadequate public infrastructure, insufficient supporting service facilities, and the homogenization of tourism products have resulted in few overnight tourists, short stay durations, and the limited realization of comprehensive tourism benefits. The tourism homogeneity issue in small towns mirrors challenges observed in Isfahan’s heritage tourism clusters [

16], indicating a global need for differentiated product strategies in peri-urban areas. Municipal authorities should allocate targeted subsidies to upgrade nightlife amenities, boosting tourist expenditure and stay duration. Leveraging regional assets, towns must strategically develop unique tourism products while strengthening infrastructure and public services to meet diverse visitor needs. For instance, Huaminglou Town may specialize in cultural heritage tourism through its historical architecture preservation; Daweishan Town in eco-wellness tourism, capitalizing on mountainous forest resources; and Huitang Town in agritourism, integrating leisure farming experiences with rural hospitality. Such mechanisms can foster synergistic tourism clusters that maximize regional resource efficiency while advancing the SDGs’ “leave no one behind” agenda.

In the future, a tiered governance approach should be drawn from the adaptive management framework in metropolitan planning, where policy instruments are dynamically adjusted based on real-time NTL and POI coupling monitoring through our proposed methodology.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has some limitations. First, the tourism POI data are sourced solely from the Amap Open Platform, resulting in a single data source. Future research could implement a multi-source data integration framework incorporating platforms such as Baidu Map and Tencent Map. Advanced data fusion techniques (e.g., spatial-temporal matching algorithms and entity resolution methods) could be employed to harmonize heterogeneous data formats across platforms, thereby enhancing dataset comprehensiveness and spatial accuracy. Second, the timeliness of POI data presents methodological challenges, as most Chinese Internet electronic maps implement daily updates to maintain accuracy, thereby impeding the acquisition of historical tourism POI records. Future studies could develop a distributed web-crawling system with periodic archival storage capabilities to systematically capture and preserve daily POI snapshots. Furthermore, they could collaborate with commercial map platforms through research partnerships to obtain privileged access to version-controlled historical POI repositories. Such methodological advancements would enable more robust temporal analyses spanning 5–10 year periods, significantly improving the predictive capacity of tourism–economic development models.