3.1. Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

For the first research question, communication opportunities provided by the parent and parent fidelity were the dependent variables. Parent communication opportunities were the central variable used to make decisions about the number of sessions for the study. For the second question, child communication was the dependent variable. The final exploratory research question, parent fidelity, used multiple variables to start to evaluate parent fidelity based on each component of the POWR strategy. Douglas and colleagues’ variable definitions and coding were utilized [

4]. The main dependent variable in the study was the communication opportunities provided by parents. These were defined as comments, choices, or questions directed at the child, with a wait time of at least 5 s or a response from the child within 5 s. Additionally, two secondary dependent variables were measured. Parent responses were defined as acknowledgments (e.g., “you want the doll”) or fulfilling the child’s communicative intent (e.g., the child asks for a doll and the parent provides it) within 5 s of the child’s communication, using either verbal or nonverbal means. Child communication was defined as any message sent from the child to the parent using speech, gestures, or AAC (e.g., the child looks at the parent while communicating and uses sign language), including both responses and initiations. This communication ended when the parent responded or after 3 s had passed.

Communication opportunities provided by parents, parent responsiveness, and child communication acts were counted during the intervention and directly after from the video recordings. Videos were chosen at random and coded by one independent, blinded observer—the last author. There is one video per session for each participant: eight videos for Dyad A and fourteen for Dyad B. Videos were selected from each phase, i.e., 40% baseline and 40% intervention. Interrater reliability was 85% for parent communication opportunities (range = 75–93%) and 90% for parent responsiveness (range = 83–95%). Data for collection ended early for Dyad 1 due to needing surgery, so we were unable to collect maintenance data for this dyad.

3.5. Parent Fidelity

In addition to the variables outlined above, videos were coded for other core elements of the POWR strategy to examine how and if parents were reaching fidelity through the modules alone. To examine step 1, “P” for “Prepare the Activity and AAC”, videos were rated using a rating scale adapted from Douglas) and colleagues (

Figure 3) [

3]. The original scale was used for parents to self-rate how well they could use the POWR strategy in the clinic prior to the study. The one similarity between the scales is the type of questions. The scale for the current study was created to measure parent fidelity during study implementation. In addition, missed opportunities due to waiting time, count of directions given, and count of the time parents modeled the AAC were also gathered. These acts, in addition to parent communication and parent responsiveness, provide insight into how parents are implementing steps two to four, “OWR”. All instances were coded and counted during transcription using the definitions from Douglas and colleagues original 2017 study [

3]. The fidelity scale was used to help analyze the data and understand the impact of fidelity on the outcome variables.

To answer the question of parent fidelity for using POWR, each element of the strategy was considered. For “P”, prepare the activity and the AAC device, parents were rated on preparing the activity and preparing the AAC device (see

Table A1). These rating scales were adapted from Douglas’s original parent self-rating scale [

3]. Intervention and maintenance scores were compared with the baseline (see

Figure 3). Elsa received high scores for preparing the activity across all phases of the intervention. Additionally, Elsa was quick at learning to prepare the SGD during the intervention phase with an average score of 88% after taking the modules. Sandra showed improvement in preparing activities after taking the modules. Although she did not pick up the skill as quickly, her SGD preparation became stable at 60% at the end of the intervention phase.

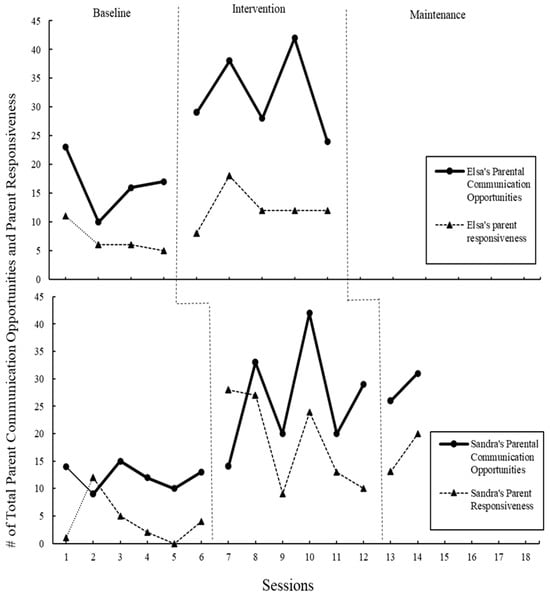

The second step of POWR, “O”, which offers an opportunity for communication, was explored by looking at the increase in parent communication opportunities, the central variable (see above and

Figure 1), and the decrease in missed communications due to directiveness (see

Figure 4). In the modules, parents were instructed on how to give communication opportunities, which included the instruction that giving directions does not elicit communication. Both parents increased parent communication opportunities; however, no change in the number of directions given was observed across all phases of the study.

Step three, “W”, waiting for the child’s communication was investigated by counting the number of missed communication opportunities due to wait time. In the modules, parents were instructed to wait at least five full seconds after providing a communication opportunity to the child. Elsa’s missed communication opportunities decreased from an average of 20 at baseline to 6 during the intervention phase. Sandra’s missed opportunities due to waiting time were relatively low at baseline, with an average of 6, an average of 3 during intervention, and an average of 3 during maintenance.

Fidelity to the final step, “R”, response to child communication was measured by counting parent responses and comparing pre- and post-baseline. Both parents increased in their total responsiveness counts throughout the study (see

Figure 1).

Last, although not a letter in the POWR acronym, modeling using the AAC is explicitly taught in the modules. Therefore, any time the parent modeled using AAC, either the SGD, sign, or another type, was counted (see

Figure 4). At baseline, Elsa modeled sign averaging 0.5 per session, and during intervention, Elsa modeled both the SGD and sign averaging 11. At baseline, Sandra did not model AAC. During the intervention, her modeling averaged 6, and during maintenance, 9.

3.6. Social Validity

To determine the functional impact of the parent training intervention, parents completed the FIATS-AAC38 [

29], the abbreviated version of the FIATS-AAC (Family Impact of Assistive Technology Scale for Augmentative and Alternative Communication). Parents were also interviewed after sessions and via written input three months after completing the study to obtain insights into the acceptability and feasibility of the modules in combination with an SGD.

3.6.1. Family Impact of Assistive Technology Scale for Augmentative and Alternative Communication

The Family Impact of Assistive Technology Scale for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (FIATS-AAC38) is a shortened version of the FIATS-AAC, designed to measure the impact of AAC interventions on children and their families. The FIATS-AAC38 is a reliable parent-reported questionnaire that identifies child and family functioning in seven domains—behavior, education, face-to-face communication, self-reliance, social versatility, security, and supervision. These are domains that are likely to be affected by AAC interventions for individuals ages 3 to 18 years. These domains are crucial because they provide a comprehensive view of how AAC interventions affect various aspects of a child’s life and their family’s well-being.

For Dyad 1, Chris’s social versatility improved, while face-to-face communication and supervision improved slightly. However, behavior and education received lower scores post-study. This is indicative that the use of an SGD had very little impact in everyday life for Chris outside of the direct aims of improved social communication. For Dyad 2, however, the findings indicate unanimous improvement for Antonio—from the highest being a full 1.6 points higher (education), with the only decrease being social versatility (−0.8). This suggests that Antonio’s behavior in the classroom, in different social situations, and with his parent/s seems to have improved post-intervention.

3.6.2. Interviews

Parents were interviewed after the completion of the study to further understand the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention. Elsa shared, “The POWR modules were easy to access at my convenience and use at home with Chris. I have found that the key of a successful therapeutic modality is the ability to execute the task at home. The modules were very accessible, and [the] format was user friendly”. Both parents report that they will be implementing the strategies learned in their everyday lives with their children. Sandra independently stated in a session that she plans to teach the strategy to other family members. In addition, Elsa shared that she appreciated the systematic approach of the POWR and she felt the intervention in combination with the SGD helped her understand her role as a communication partner with her child. Three months after the study was complete, Elsa reported that she was still using the strategy and device with her child. Her child, Chris, is now receiving AAC services from a speech-language pathologist at school and is using a Switch AAC. Overall, the parents found the modules and implementation feasible and acceptable, and neither parent mentioned any difficulties or hardships in implementing the intervention with their child.