1. Introduction

In the last century, due to population growth and tourism activities, coastal areas have experienced significant urban development [

1,

2,

3]. The development of recreational and cultural activities linked to international tourism began essentially in the 20th century [

4] when European and USA’s citizens started to travel abroad on holidays [

5,

6,

7]. In recent decades, there has been an increase in Russian, Japanese, and, especially, Chinese visitors [

8].

Tourism is one of the largest growth industries in the world [

9] and coastal and marine tourism is the leading part of this industry [

10], representing billions of US dollars [

7]. In the Tropics, profits related to beach tourist activities represent a relevant part of many countries’ GDP [

9] and, among them, there is Cuba [

11,

12]. In 2018, the country was the second in the Caribbean (after the Dominican Republic) for international arrivals (4684 million), with associated incomes of USD 3000 million, which contributed to 10% of its GDP [

9].

Considering that the tourism trend is globally growing and Cuba wants to increase the number of visitors and related revenues, it is essential to identify the expectations of coastal tourists. Five main parameters (the “Big Five”) are of the uppermost relevance for beach visitors, i.e., very good water and sediment quality, safety, facilities, no litter, and excellent scenery [

13]. Concerning the specific relevance of sand’s beach colour, many beach visitors were asked how important it was in a range between 1 (poor) to 10 (high) in choosing a beach site holiday and an average final score of 6.4 was obtained [

14]. Thus, tourists are usually interested in wide beaches composed of fine white sand with blue water colour and luxurious vegetation in the backbeach [

14,

15]. Therefore, beach sediment characteristics represent a vital asset for tourism, especially in tropical countries where the “Sun, Sand and Sea” (3S) market [

16] is the main driving factor and beach sediment composition (e.g., textural characteristics and colour) is the only one that can be partially managed [

15].

A major concern is also represented by beach surface reduction or complete loss linked to coastal erosion and inundation processes related to maritime climate, long and cross-shore sediment transport, and the reduction in river supplies. This is a major problem affecting most of the world’s coastal areas, including beaches and dunes and other important coastal environments such as salt marshes and mangroves [

17,

18,

19].

In the last three decades, Cuba has managed coastal erosion processes very well, avoiding the construction of coastal protection structures and promoting nourishment programmes [

20]. Rigid protection structures usually only solve problems at the very local scale and favour erosion in nearby areas; furthermore, they generally produce dangerous currents, loss of beaches’ ecological value and biodiversity, and diminution of landscape value [

13,

14]. Comprehensive nourishment projects of beaches and dunes were carried out in Cuba, where Varadero is probably the most representative example [

21,

22]. The most important achievements of such management initiatives were the improvement in the coastal scenic value, e.g., illegal constructions on the dunes’ ridges were demolished and dunes were nourished and revegetated, the increasing of beach width and carrying capacity, and the protection from hurricanes and storms of human settlements on the back of dunes’ ridges [

20,

23].

Borrow sediments (i.e., sand used to fill the beach) used in the artificial fills carried out in Varadero were dredged in the nearby nearshore areas, which presented a similar composition and their colour was slightly darker [

24]. Compatibility of the borrow sediment with the native one is primarily based on grain size and mineralogical characteristics that determine grain density, form, and colour. The

Coastal Engineering Manual or CEM [

25] gives this “general recommendation”:

a nourishment project should use fill material with composite median grain diameter equal to that one of the native beach material. Krumbein and James [

26] proposed an equation to calculate the volume of borrow material needed to obtain a unit volume of sediments with the same grain size distribution as the native one. To calculate its stability, previous authors proposed a nomogram with inputs of mean size and sorting of borrow and native sediments. Other researchers proposed the Fill Factor [

27] and the Overfill Factor [

28]; the latter is now the most used system in beach nourishment projects [

25].

Later, the calculation of a Stability Index to assess borrow sand stability was proposed [

29] and a detailed method to define the compatibility of chromatic aspects of borrow and native sands was introduced [

14,

29]. International experience shows that to carry out a sound nourishment project, it is mandatory to properly investigate coastal sediments (i.e., their grain size, mineralogical, and chromatic aspects) that represent the relevant economic resources [

30].

This paper analyses the textural, mineralogical, and chromatic characteristics of sediments collected from 90 beaches in Cuba. Therefore, this work constitutes a relevant database at a national scale on beach sand characteristics that will be very useful in managing coastal areas and properly designing nourishment plans, especially in more sensitive sectors or tourist areas.

2. Study Area

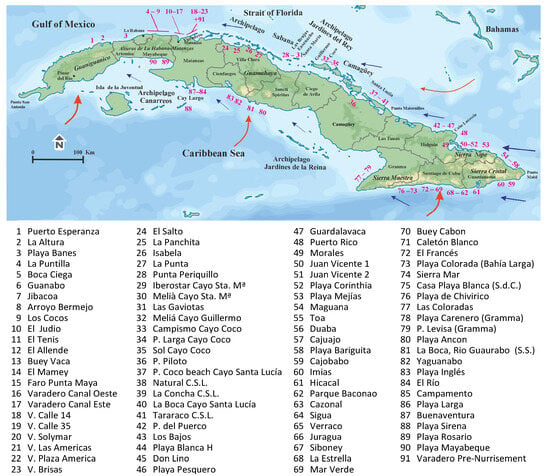

The Archipelago of Cuba (

Figure 1), which presents a total extension of 110,922 km

2, is located in the Caribbean Region. It consists of the main island of Cuba, the Island of Youth (Isla de la Juventud), and more than 1200 smaller islands and cays (low banks or reefs of coral, rock, or sand, and also denominated keys). The main chains of cays and reef crests are observed on the northern and southern coasts of Cuba. On the northern coast is found the longest one (450 km), i.e., the Archipelago Sabana-Camagüey which includes all the cays from Varadero to Santa Lucía (

Figure 1). The central part of it, some 200 km in length, is named Jardines del Rey and shows five main cays in the provinces of Ciego de Avila and Villa Clara. In the former lies Cayo Coco, the largest cay consisting of 22 km of fine sand beaches and Cayo Guillermo, with 5 km of sand beaches. At the latter are located Cayo Santa María, a UNESCO-protected area consisting of 10 km of sand beaches; Cayo Ensenacho, with just two beaches; and Cayo Las Brujas with 2 km of sandy beaches. On the southern coast of Cuba are the archipelagos of Jardines de la Reina and Canarreos (

Figure 1).

From a geological point of view (

Figure 2), the Cuban territory is the result of the subduction of the Caribbean plate under the North and South American plates [

31]. Two structural domains are observed: the oldest and allochthonous folded substrate and the youngest and autochthonous substrate. The former is made up of different fragments of continental and oceanic nature from the North American, Caribbean and Pacific plates. The neo autochthonous is represented by sedimentary rocks and structures that originated in the Upper Eocene at its present location [

31,

32,

33].

Different internal allochthonous mountainous chains in Cuba were formed during its geological evolution. They are oriented in an east–west direction according to the insular arch of The Greater Antilles. In the west, the Guaniguanico Complex, which is 160 km in length, has a maximum height of ca. 700 m and is developed along the Pinar del Rio and Artemisa provinces. It is formed by two mountainous chains, i.e., Sierra de los Organos and Sierra del Rosario, composed of sedimentary (essentially sandstones and limestone) and metamorphic rocks of the Jurassic age [

31]. Close to La Habana, there is a folded and faulted sedimentary (limestone) Cretaceous rock chain, namely the Las Alturas (The Heights) of La Habana-Matanzas, with a maximum height of 380 m (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). In the central part of Cuba is observed the Complex of Guamuhaya, which includes the Sierra Trinidad and Sierra Escambray in Sancti Spíritus, Villa Clara, and Cienfuegos provinces which reach a maximum height of 1140 m. It is composed of ophiolites and volcanic and metamorphic rocks from the Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Paleogene ages. In the eastern part of Cuba, along 250 km including the provinces of Granma, Santiago de Cuba, and Guantanamo run the Sierra Maestra, Sierra Cristal, and Sierra Nipe, which reach a maximum height of 1974 m. They are composed of ophiolites and other volcanic and sedimentary Cretaceous and Palaeogene rocks [

34] (

Figure 2).

Cuba has a tropical seasonally humid climate (“Aw”) according to the Köppen–Geiger classification [

35] with an average temperature of 25 °C. The dry season is from November to April and the least rainy month is December. The wet season goes from May to October, with the heaviest rains in August [

36]. Main meteorological events are related to Trade winds (

Alisios) approaching from the Atlantic Ocean, tropical cyclones (from August to October), and cold fronts from the Gulf of Mexico [

37]. Another important characteristic of the Cuban climate is the large number of hours of sunshine per year. La Habana enjoys a total of 2935 h of sunshine per year, which makes the country very attractive for tourism.

The Cuban hydrographic network is composed of over six hundred watersheds and sub-watersheds and more than two hundred rivers flow into the sea surrounding Cuba. They usually show limited flow with important flooding events concentrated during the rainy season. The coast is a microtidal environment with exposed and sheltered (because of cays and coral reefs) sectors [

38,

39]. The significant wave height is lower (0.25–0.5 m) on the southern coast from Cape San Antonio to Sierra Maestra than on the northern coast, from Punta San Antonio to Cabo Lucrecia, and the southeast coast (with wave values between 0.5 and 1 m), being higher in the northern part of the east coast (1.25 m) [

40]. The main directions of arrival of waves and coastal drift under normal wind conditions are from the first quadrant for the northern coast and from the second quadrant for the southern coast of Cuba. In winter, under cold front conditions, the dominant sediment transport direction is westerly. Extreme events (hurricanes) mainly arrive from the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, mostly affecting the west of Cuba and the southeastern areas and, to a lesser extent, the southern central coast and the northern keys [

40]. The coasts are characterized by mangrove swamps (mainly in the southern coast of the Artemisa, Mayabeque, Sancty Spiritus, El Ciego de Avila, Camagüey, Las Tunas, and the western part of Gramma provinces and in the sheltered coastal area behind the cays in the northern (especially) and southern coast of Cuba); sandy shorelines (along the cays); and rocky substrate coastal sectors with terraces or cliffs recorded in the northern coastal sectors of the Artemisa and Mayabeque provinces, in the southern coast of the Cienfuegos Province and the oriental zone of Cuba [

32]. Terrigenous river supplies have been significantly reduced in past decades [

41] because of the construction of more than 200 dams and 800 micro-dams.

Only 30% of the population (ca. 3 million) live along the coast, and the most common tourist areas are La Habana and Varadero. The Archipelago of Sabana-Camagüey (especially) and the archipelagos Jardines de la Reina and Canarreos have many international visitors [

42].

3. Materials and Methods

Two extensive field campaigns were carried out to explore a large number of localities to ensure a very high representation of beaches along the entire coast of Cuba. Sands were taken from the beach surface in the middle part of the backshore at 90 sites (

Figure 2). In addition, a sample of sand collected from Varadero beach in the early 1980s, before the nourishment works, was analysed.

Several techniques were used to characterize the sediments of Cuban beaches. Firstly, macro-photographs were taken at a distance of 60 cm with a reflex camera, always using the same white light device to avoid variations in colour.

An optical stereomicroscope study was also carried out with a Leica DFC 450-M 205A binocular loupe with an attached camera using the LAS© software (v. 4.7). This technique has allowed the initial identification of shells of organisms, minerals, and rock fragments.

Textural analyses were performed using the open-source Basegrain© software (v. 2.2.0.4), written in Matlab (v. 2012) [

43,

44], applied to the photographic images captured with a Leica digital microscope and subject to image processing, edge detector filter included [

43,

45]. This allowed the retrieval of the

a and

b axes for each grain, from which the samples’ mean diameters in microns were obtained.

These values, converted in phi units, allowed us to obtain the granulometric cumulative curve of each sample on a log-probability scale and calculate mean size (Mz) and sorting (σI) textural parameters according to [

46]. From the beachgoers’ perspective, they represent the most representative beach characteristics and are commonly used to assess sediment stability in beach nourishment projects [

25].

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to identify the mineralogy of each sample of sediment. The samples were ground until passed through a sieve of 0.063 mm mesh size. A mineralogical analysis was performed with a Bruker© D8-Advanced ECO Diffractometer at a steady voltage 40 kV and 30 mA with radiation Cu-Kα = 1.5405 Å. The mineralogical composition was determined by comparing the intensities of each mineral phase with the EVA© software (v. 3.0) database references. The semi-quantitative analysis of different mineral phases followed the reference intensity ratio (RIR) value method using the RIR included in the database of the software EVA©.

Morphological and textural features studies were carried out through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Nova Nano SEM450 from FEI©. The chemical composition of some minerals present in the beach sediments was carried out with an EDAX AMETEK detector equipment from TEAM©.

The qualitative and quantitative chemical composition of some mineral grains which were not clearly identified by the EDX microanalysis was carried out by X-ray fluorescence (XRF), specifically with a Bruker MP4 Tornado instrument.

The chromatic parameters (L*: lightness; a* and b*: related to the opponent colours yellow-blue and red-green) of the investigated samples were obtained from previous research [

24]. These authors carried out colour determination using CIEL*a*b* 1976 colour space, Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage [

47].

The statistical study was carried out using the free software “R” [

48]. The data used are related to colour and mineralogical composition. The units of the data were standardized using the z-score standardisation. Descriptive statistical treatments using Pearson’s coefficient and different multivariate techniques, i.e., the Principal Component Analysis and the cluster analysis, were applied in order to sort the samples investigated.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characterisation by Binocular Stereomicroscopy

The microscopic study of the beach sediments allowed the identification of their principal components and the compilation of an extensive photographic catalogue.

Figure 3 shows some photographs illustrating the variety of grain size, mineral components, and colours of the sediments studied.

In the sediments ooids and bioclasts of different organisms were also seen, always consisting of benthic organisms typical of coastal and shallow shelf environments (

Figure 4). The precipitation of ooids is favoured by the swaying produced by waves in high-energy environments (Playas Sirena-88, and Meliá Cayo Santa María-30) and may subsequently accumulate in nearby more restricted areas. In these beaches very few bioclasts were observed, e.g., well-preserved hyaline foraminifera of the Rotalidae group such as Ammonia. Also, very few bioclasts (i.e., bivalve fragments) were observed in the coarse sand and gravel beaches in the eastern part of the island. The association of benthic organisms found on the other beaches was composed of bryozoan and coral remains; fragments of lamellibranchs, gastropods, and echinoderm; and rarely sponge spicules and hyaline (Elphidium, Lenticulina, Nodosaridae, and Ammonia), miliolids (Triloculina), and benthic foraminifera. Some uncoiled cephalopods (Spirulidae) and scaphopods (Dentalium) were also observed. The sands of Rosario-89 and Mayabeque-90 beaches stand out because they were almost entirely composed of large quantities of lamellibranch and gastropod fragments (

Figure 3E and

Figure 4C).

4.2. Grain Size Statistics and Parameters

The grain size statistical parameters (mean “Mz”, sorting “

σI”) have been calculated from the grain size distribution curves using the logarithmic method of Folk and Ward [

48], and the results are expressed in micrometres (

Table A1) and phi (arithmetic scale) in

Figure 5.

The coarsest sediments were found on the beaches of Cajobabo-59 and Imias-60 (−2.14 and −1.76 phi, 4542 and 3659 µm, respectively), while the finest sediment was observed at Playa Mejías-53 (2.37 phi, 199 µm).

Figure 5 shows the grain size and sorting (in phi and µm) of the 91 samples. Regarding the mean grain size (Mz,

Figure 5), a wide variation is observed, reflecting a diversity of sedimentary sources and depositional environments. Finer grains are typically associated with low-energy conditions, such as protected beaches sheltered by cays or located inside deep bays, whereas coarser grains are found on high-energy beaches, such as those located in the eastern part of the island, exposed to strong waves. Additionally, the presence of exceptionally high values (>1000 µm) may correspond to areas close to the sources of coarse clastic materials, where beaches are fed by rivers reaching the coast after a short course from near high mountains. The degree of heterogeneity is also significant (

σI,

Figure 5). Thus, beaches with well-sorted grains (low St. dev. values) suggest stable and homogeneous energetic environments.

Poorly sorted sediments (high St. dev. values) usually indicate a mixture of materials from different sources or episodic high-energy events that transport particles of varying sizes. Generally, the values are concentrated in the moderately well-sorted (MW) range.

Regarding grain size, the range observed is similar to that reported for open-system beaches (e.g., [

49]), reinforcing the hypothesis of a predominant sediment transport driven by moderate to high energy conditions.

4.3. The Colour of Cuban Beaches

As one of the objectives of this study is to try to establish a relationship between the colour of the beaches and their mineralogy, it is necessary to present the results of the study carried out by Pranzini et al. [

24] on the colour of the beaches of Cuba that used the same samples that have been analysed in this work (

Table A2 and

Figure 6). It is possible to observe a great variability and to differentiate several sectors according to sediments’ lightness and colour. White sand beaches with high values of lightness are concentrated in the cays and Varadero, the most popular international tourist destination in the country, and grey to dark sediments prevail especially in the southern, eastern, and western parts of Cuba which are essentially frequented by national tourists; gravel and coarse sands with dark sediments are less attractive for the international visitors.

The comparison of the characteristics of Cuban sands with the ones from other famous 3S international tourist destinations [

12] highlights that most of such destinations have sand lightness values similar to the Cuban beaches of Varadero (L* between 50 and 70), like those of Essaouira (Morocco) or Santa Elena and Galapagos (Ecuador). Others are even brighter, like those of Santo Domingo, Australia, or Zanzibar (with L* between 70 and 85). Only the dark beach sediments of Bali or Guatemala show L* < 45.

The colour-related parameters (a* and b*) show more uniform values (

Table A2), with a* values ranging from the most greenish (−1.70) at Imias beach (60) to the most reddish (9.32) at Playa Colorada (73). The most yellowish b* values (21.94) are found at Playa Colorada and the most blueish (4.11) at Playa Bariguita (58).

4.4. Mineralogy of the Cuban Beaches

The total mineralogy of each of the Cuban beaches studied is presented in

Table A3.

Figure A1 shows some X-ray diffractograms characteristic of the different types of mineralogical compositions found.

Besides the classic species of calcium carbonate (calcite and aragonite) and calcium magnesium carbonate (dolomite), calcium, magnesium, and manganese carbonate are also present. This carbonate, in X-ray diffraction, shows a diffraction pattern close to those of magnesian calcite and kutnohorite, a mineral species of rare occurrence in the modern world sediments records [

50]. In addition to calcium, kutnohorite contains manganese (Ca Mn (CO

3)

2) and has the crystal structure of dolomite, which forms a solid solution by replacing manganese atoms with magnesium (Ca (Mn-Mg) (CO

3)

2) [

50].

According to the results presented in this study, the mineral species present would correspond to terms of the kutnohorite–dolomite solid solution.

Three main reasons support such a result: (i) In the X-ray diffractogram were observed reflections coincident with, or very close to, those of the kutnohorite in the EVA© software database, with very slight displacements that would obey the higher or lower substitution of Mn by Mg. All the highest intensity reflections were recorded, specifically those corresponding to the following d spacings in Å: 3.795 (intensity 3 out of 10), 2.985 (10), 2.769 (1), 2.459 (3), 2.251 (4), 2.063 (4), 1.867 (4), and 1.843 (3). (ii) Microanalyses performed in the scanning electron microscope gave carbonates with calcium, magnesium, and manganese. (iii) Similarly, by means of X-ray fluorescence analysis, carbonates were also found and mapped with manganese. There is no information about the presence of manganese in the sediments near the cays and, undoubtedly, more mineralogical and crystallographic investigations will be necessary.

Regarding the total mineralogy found in the sediments studied, the beaches of the central zone of the north coast, essentially developed on cays (from Varadero to Nipe Bay, numbers 17 to 49 in

Figure 1 and

Figure 6), are mainly composed of aragonite, kutnohorite, and calcite (65, 17, and 9%, respectively). A group of beaches on the northwest coast (numbers 3 to 12 in

Figure 1 and

Figure 6) show, in addition to lower contents of aragonite and kutnohorite, relevant amounts (13–51%) of plagioclase and the presence of amphibole and/or serpentine of around 10%. The quartzose composition of the westernmost beach, Puerto Esperanza (1), with more than 80% quartz, and the aragonitic composition of beaches formed by ooids (30, 31, and 88 in

Figure 1) are striking.

On the eastern coast (numbers 50–78) are located the beaches with the highest concentration of a mineral association formed by ferro-magnesian silicates: amphiboles, pyroxenes, chlorite, and serpentine. They also present plagioclase contents that, although variable, are quite high (around 30%).

Dolomite appears in small quantities (less than 5%) in a few southern beaches. Pyrite is present in two of the beaches (numbers 56 and 82) and phyllosilicates (biotite) in beach number 81. Ilmenite is present on five beaches at the northeastern extreme of the island (51–53 and 55–56) and siderite, haematite, zircon and apatite are found in very few samples and only at trace level.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

A statistical analysis was performed to establish relationships between the colour and the predominant mineralogy of Cuban beach sediments. Sixteen quantitative variables were used, i.e., the three CIEL*a*b* colour parameters and the thirteen minerals found.

The highest relationship is established between the mineral aragonite and the L* component (Lightness) of the sand colour. The correlation matrix through Pearson’s coefficient (0.786) and the covariance (237.72) confirm the positive linear dependence between these two variables. Lightness and kutnohorite percentages are also similarly related but with lower values (0.55). A negative relationship was established between the presence of these two minerals with another group of minerals including plagioclase, chlorite, pyroxenes, amphiboles, and serpentine. When considerable amounts of aragonite and kutnohorite are present on the beach, the second group of minerals is almost absent, as demonstrated by the linear relationships between the two groups of minerals (coefficients from −0.75 to −0.38). The cluster analysis evidences the configuration of four groups as the best discrimination (

Figure 7).

The first group (1 in

Figure 7), mostly corresponds to the beaches of the northern cays of the island, and within this group are also the beaches of the southern cays and the pre-nourishment Varadero beach sample. All these beaches are of carbonate composition and the sum of aragonite and kutnohorite is close to 90%. The second group (no. 2 in

Figure 7) contains the northwestern beaches and some others where in addition to carbonates, there are also recorded low contents of detrital minerals represented by the sum of quartz, plagioclase, amphibole, pyroxene, serpentine, and chlorite. This last association of melanocratic minerals, together with quartz and plagioclase, is characteristic of the beaches grouped in the third group (3 in

Figure 7), which are located on the eastern coast of the island. Finally, the fourth group (4 in

Figure 7) consists of only the three samples with the highest quartz contents, between 42 and 82%, i.e., beaches numbers 1, 24, and 27.

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) allows for the visualisation of the relationships between mineralogy and beach colour (

Figure 8). In the two-dimensional representation of the two principal components, two major associations can be observed with, respectively, positive and negative PC1 values. In the right part of the diagram (with positive PC1 values), the colour-related variables (a*, b* and L*) are associated with the minerals aragonite, kutnohorite, and calcite and their sum. In the left part of the diagram (with negative PC1 values) are the variables corresponding to amphibole, pyroxene, serpentine, and chlorite and their sum together with plagioclase and quartz; in this sector are also found the other melanocratic minerals, i.e., ilmenite, biotite, and pyrite (

Figure 8).

The location of the samples according to the main components (

Figure 8) confirmed the grouping of similar samples as observed in the case of the cluster (

Figure 7). Therefore, we can observe the presence of aragonite+kutnohorite+calcite in the cays due to the autochthonous carbonate sedimentation processes that take place in nearby areas, and the presence of melanocratic minerals together with quartz and plagioclase in association with minerals linked to detrital sedimentation in the samples located in the eastern coast of Cuba.

4.6. Correlations Between Colour, Grain Size, and Mineralogy

Taking into account the results of the textural, chromatic, and mineralogical characterisation, a series of relationships can be established among such parameters and with the origin of the beach sediments.

The beaches of Cuba show colour diversity, more in terms of lightness (L*) than in terms of the chromatic a* and b* parameters [

24]. The lightest beaches are those formed in the central area of the north coast, many of them located on the cays and are naturally nourished with biogenic sands containing abundant organisms from nearby reef areas. On these light-coloured or white beaches, composed of fine and medium-sized sands, the mineral association of aragonite>>kutnohorite>calcite predominates (

Figure 9). The remains of corals, calcareous algae, bryozoans, and the presence of hyaline foraminifera such as Lenticulinae, Elphidium, Nodosarids, and Ammonia or sandy foraminifera are frequent. Some porcelaneous calcareous foraminifera were also found as a type (i.e., milliolarians) of Triloculina (

Figure 4D).

The darkest beach sediments are located on the southeast coast, in the provinces of Holguín, Guantánamo, Santiago de Cuba, and Gramma (

Figure 2). These include beaches of coarser grain size, gravel, and coarse sand. The minerals associated with low values of lightness are chlorite, amphibole, pyroxene, and serpentine (

Figure 9). Most of them are green or black in colour, although they are also associated with the presence of plagioclase, which is usually light-coloured.

Ilmenite is also recorded on beaches in the eastern part of the island, on the northern slopes of Sierra Nipe (East of Holguín province and West of Guantánamo province), specifically in a region near Mejías beach (number 53 in

Figure 1). In this area, some authors [

52,

53,

54] have mentioned the existence of sandy placers containing, in addition to ilmenite, other heavy minerals (chromite and magnetite) and precious elements (gold and silver). Such minerals are deposited there because of the interaction of alluvial and marine processes and can form mineral deposits of economic interest.

These dark minerals are usually part of the coarse grains of rock fragments (

Figure 9) from the Mayarí and Boa-Maracoa ophiolitic complex (

Figure 2) [

52], rich in gabbros, peridotites, and serpentinites [

53], and from the basic rocks of the Cretaceous and Palaeogene volcanic arcs of Sierra Maestra and the aforementioned Nipe and Cristal (

Figure 2), where tuffs and basalts are frequently found.

In addition, coasts without a wide continental shelf prevent, with very localised exceptions, the growth of reefs that provide light-coloured biogenic components. This is the case of the beaches of Cazonal and Campamento (numbers 63 and 85 in

Figure 1), which appear as isolated beaches of very light colours, on a coast dominated by dark colours. In Campamento, the dominant minerals are plagioclase and aragonite, and in Cazonal, aragonite and kutnohorite.

Playa Rosario and Playa Mayabeque (numbers 89 and 90 in

Figure 1 and

Figure 9) have a great abundance of bioclast formed by gastropods and fragments of lamellibranchs presenting brown or dark brown colours. Playa Colorada (73) has the reddest colour of the entire Cuban coastline (L* = 53.03; a* = 1.28; b* = 12.74), which is linked to the incipient alteration of calcium carbonates and kutnohorite (

Table A3). The beach with the greenest colour is Imias (number 60 in

Figure 1: L* = 48.54; a* = −1.7; b* = 4.76) where in addition to pyroxenes and amphiboles, the highest percentage of chlorite is found (30%). In this case, this green-coloured mineral would come from the volcanic rocks of the Cretaceous arc that outcrop in the vicinity of the Sierra del Convento (

Figure 2).

5. Coastal Management Implications

Most of the sediments studied consist of medium to fine sands that, along the cays in the archipelagos of Jardines del Rey and Canarreos, are essentially composed of carbonates. Such leucocratic minerals give rise to white, attractive sands with lightness values from 64.81 to 80.48. Other sandy beaches located on the eastern coast are composed of melanocratic sediments consisting of different ferro-magnesian silicates with lower lightness from 35.12 to 59.3, giving dark green and grey beaches (

Figure 9).

All the gathered information is very useful for different aspects related to Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) issues and this is especially true in the case of Cuba, where visitors are principally interested in beach tourism [

24].

Beaches serve also as a defence for backing coastal settlements and ecosystems protecting them from increasing sea levels and high-energy events due to progressive climate change as recorded in Cuba by Tristá Barrera et al. [

20].

When coastal erosion threatens the survival of beaches or renders them so narrow that they can no longer fulfil the tourist and protection functions, coastal sediment management becomes an essential component of the ICZM. Therefore, robust and up-to-date data on beach sediment characteristics are very useful for coastal managers to maintain and even attempt to improve their quality and ultimately promote their tourism development and protect them from disturbance [

29]. In this context, many regions or states are developing databases containing information not only on the evolutionary trends of their coastlines (e.g., the Atlas of Italian Beaches, whose first sheets were published in 1986, [

55]) but also on the textural, petrographic, and colourimetric characteristics of sediments of both eroding and accreting beaches [

56,

57,

58]. These databases also include information about nearshore sediments or those found on the coastal shelf, which can be used for artificial beach nourishment in areas affected by erosion.

This paper contributes to improving the national coastal sediment management plan for Cuba, i.e., the collected data represent a valuable tool for assisting decision-makers and designers in identifying cost-effective solutions for shore protection within the framework of the ICZM. Regional Sediment Management (RSM) plans to optimize sediment use through adaptive strategies applied across multiple projects [

59,

60]. This approach enables resource optimisation by ensuring the best possible management of available sediments in case of beach nourishment works, e.g., sand transfer from one accreting beach to another erosional one. Such work has to consider the required volume of sediments, compatibility with native sediments, and transportation costs while preserving the natural characteristics of the beaches to be artificially filled. Nourishment projects usually especially take into account grain size and, secondarily, mineralogical characteristics that determine grain density, form, and colour.

In Cuba, sound management of coastal erosion processes was carried out avoiding the emplacement of rigid protection structures and favouring beach/dune nourishment projects with sediments usually gathered from nearby nearshore areas.

Concerning the the borrow sand characteristics, particular attention was devoted to grain size and, secondarily, to sediment colour and lightness, which are also of extreme relevance to maintaining the appeal of the original beaches. Cuban beaches have very good scores concerning sand lightness and colour in the cays and Varadero, which are essentially international tourist destinations [

61]. It is mandatory to maintain sand quality at such sites and emblematic was the case of Varadero which was nourished by dredging sand from the platform (2.5 million cubic metres from the mid−1980s to the end of the 20th century [

22]). The present study includes a sample of sand from Varadero prior to beach-filling works [

24] and the results show that its mineralogical composition consisted almost exclusively of aragonite and kutnohorite, with its colour among the three lightest scores of the whole country. Anthropogenic inputs of sand that, according to the results recorded in this paper, contained more bioclasts and little amounts of amphibole, serpentine, and chlorite, caused a change in its colour and nourished sand had greyish tones and therefore, was slightly darker than the original one.

Moreover, the data collected on the sediment mineralogy of Cuba’s beaches are very useful for understanding sediment sources, e.g., the erosion of cliffs and, especially, the streams and rivers that supply sediments to the coastline, as well as their area of origin within a specific river’s watershed and the impacts of watershed constructions (e.g., dams) on river’s supplies to coastal areas. In addition, the recorded data can be incorporated into educational materials particularly useful for geotopes to explain to beach visitors the origin, formation processes, and characteristics of beach sand. Textural and mineralogical characteristics of beach sediments, besides aiding in understanding the origin of sediments and the impact of marine or watershed constructions on sediment balance, can also be incorporated into educational materials. These materials can explain beach characteristics and formation processes, particularly for geosites such as some beaches in Sardinia, Italy [

62], or Chesil Beach in the UK [

63].

Further studies are required to complement the data presented in this paper, such as the understanding of the dynamics of the beaches and the factors that may condition the precipitation of carbonates and the identification of potential borrow areas. The characterisation of historical and recent coastal evolution trends by means of aerial photos and/or satellite images is also of relevance: such findings will allow us to distinguish between erosion and accretion areas along the Cuban coast. According to the results obtained, detailed topographic monitoring programmes can be planned at specific, problematic sites [

24], and mineralogical data on beach sediments can be used to reconstruct their origin (e.g., coastal reef or land erosion) and supplying mechanisms (waves and currents or rivers) [

57]. The obtained results will allow us to adopt sound management actions according to the very specific observed problems [

64].

6. Conclusions

Collected information on the mineralogical composition, texture, and colour of the sediments of Cuban beaches in this paper will be very useful since they constitute a major step towards improving the comprehensive management plan of the investigated coastal sites by local and national authorities.

The database obtained is of paramount relevance to project comprehensive studies on the management of coastal sediments. As an example, the mineralogical characteristics of beach sediments give useful information on (i) the streams and rivers that supply them to the coastal area and, therefore, about the possible impacts of the existing or projected dams or other man-made structures; (ii) the longshore littoral transport of sediments, allowing us to define coastal cells and the relations among them; and (iii) to complete, along with the colourimetric characteristics of sediments, all the required information to carry out comprehensive nourishment works that, at a world scale, usually take principally into account grain size and, only in a secondary way, the mineralogical and colourimetric characteristics of borrow and native sediments, which allows us to preserve the existing coastal landscape characteristics at sensitive and great tourism sites, such as the cays. Further investigations have to be devoted to the reconstruction of coastal evolution trends to determine the spatial distribution of erosion/accretion areas in order to project sound sediments’ by-pass works from accreting to erosion areas taking in mind the mineralogical, textural, and colour characteristics of both native and borrow sands.

The collected information can be used in future for the promotion and development of such beaches that, because of their peculiar colour associated with their geological characteristics, can become geosites and thus, work as the pole of attraction for visitors, as in the case of Imias and Playa Colorada in the southeastern coast of Cuba.