1. Introduction

Breastfeeding is a cornerstone in supporting the survival, nutritional needs, and developmental progress of infants and young children while also promoting maternal health [

1,

2].

The properties of breast milk that protect the infant from a wide range of diseases, particularly infections, are well documented (

Table 1).

The effectiveness of breast milk is attributed to its diverse array of bioactive molecules that have been shown to offer protection against infections [

20,

21], reduce inflammation [

22], enhance immune function [

23], and influence the infant microbiome [

14,

24]. These benefits are particularly vital during infancy when the innate immune system is still developing. In response to the emergence of novel viruses that can cause pandemics and the increased vulnerability of specific populations to severe infections, both national and international research initiatives are focused on identifying new antimicrobial agents or natural substances with potential efficacy against infections. In this context, breast milk has gained significant attention, becoming the subject of numerous studies. Preclinical evaluations of human milk are increasingly being translated into clinical applications, with the possibility of a large-scale production of its active compounds [

25].

In lactating mothers who have been immunized, IgG and IgA antibodies have been identified in breast milk [

26], offering passive immunity to the infant and safeguarding against infections during the first year of life [

27]. In the event of an infection in either the mother or the infant [

28], breast milk serves as a source of numerous antipathogenic and anti-inflammatory bioactive factors that contribute to the infant’s immune defense [

29].

The mother’s initial response to infection contributes specific immunological factors to breast milk, which could help prevent infection or mitigate the severity of the illness. In the breast milk of mothers infected with various microorganisms, a range of immune and anti-inflammatory biomarkers, including immunoglobulins A (IgA) and G (IgG) [

8], cytokines and chemokines [

30], as well as enriched levels of lactadherin, butyrophilin, and xanthine dehydrogenase, have been identified [

31].

The cultivation of viruses from RNA-positive breast milk samples collected from infected mothers appears to be unachievable as no replication-competent virus has been detected in any of the samples, including those that tested positive for viral RNA. These findings indicate that the virus particles identified in breast milk may not be capable of causing infection [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Even if the infectious agent is excreted in breast milk, evidence suggests that it does not lead to infections in infants [

36,

37,

38,

39].

Recent studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that breastfeeding may exert an inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, research indicates that SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and Middle East respiratory syndrome are not transmitted via breast milk [

40,

41,

42,

43].

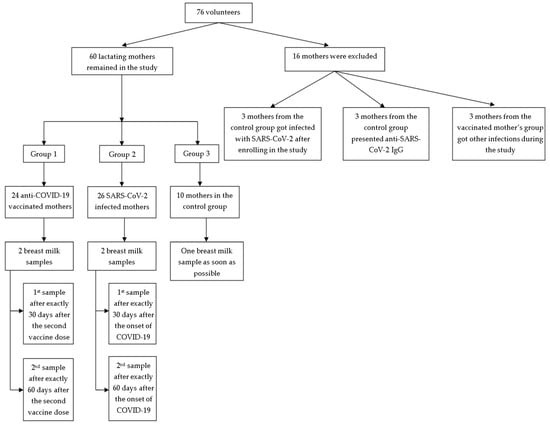

Aim of the Study: Numerous inquiries have emerged regarding the potential transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus or vaccine components to infants or young children through breastfeeding by mothers who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated against COVID-19. While many studies have addressed and alleviated these concerns [

8,

30,

44,

45], the present research seeks to emphasize the beneficial effects of breastfeeding for infants of mothers affected by the virus or vaccinated against COVID-19. Consequently, our study aims to investigate whether bioactive components with antimicrobial properties, previously identified in various breast milk contexts, are secreted or show alterations in concentration in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection or immunization status.

In selecting the proteins for analysis, we focused on those known for their antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory roles, which have been studied in the context of COVID-19 and detected in breast milk under various conditions. Accordingly, we have chosen to assess six antimicrobial proteins—chitinase 3-like 1 (C3-1), furin (F), granzyme B (GB), lactoferrin (LF), lactadherin (LD), and tenascin C (TC)—in the breast milk of mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared to those vaccinated against COVID-19.

To the best of our knowledge, there is limited data regarding the specific role of human milk in combating COVID-19. However, numerous studies have extensively documented its antimicrobial properties against various viral agents.

4. Discussion

In our study, we compared the immune response triggered by natural SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination, providing valuable insights into the type and quality of immunity transferred to the infant through breast milk.

The investigation into the biomarkers present in the breast milk of mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated against COVID-19 was driven by the need to understand how maternal immune responses are transferred to infants. This research holds significant implications for infant immunity, public health, and the long-term clinical outcomes for infants exposed to COVID-19-related immune factors through breastfeeding. By studying these immune components, we aimed to better comprehend how maternal infection or vaccination might influence neonatal health in the context of COVID-19.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the levels of the tested biomarkers between two distinct groups—those infected with SARS-CoV-2 and those vaccinated against COVID-19—in order to assess differences in antimicrobial protein profiles. This comparison sought to determine whether infection or vaccination induced more robust or effective antimicrobial responses in breast milk, explored the potential protective effects these bioactive proteins might have on breastfeeding infants, particularly regarding the prevention or mitigation of COVID-19 infection, and evaluated how maternal infection or vaccination influenced the transfer of passive immunity to infants via breast milk.

Furthermore, the study intended to assess whether breastfeeding provides additional immune benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic, as indicated by changes in biomarker levels, and aimed to provide evidence to guide public health recommendations for breastfeeding practices among mothers who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated against COVID-19.

Newborns possess an immature immune system, making them highly reliant on maternal antibodies, antimicrobial compounds, and innate immunity for protection against infections. Consequently, breast milk is rich in immunomodulatory substances, antibodies, and antimicrobial molecules that provide essential protection [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it became essential to explore how the immune profile of breast milk changes in mothers who have either been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated. Our identification of biomarkers such as C3-1, F, GB, LF, LD, and TC in this context revealed that maternal protection is effectively transferred to the child, significantly influencing neonatal antimicrobial defense.

LF and LD are prominent bioactive proteins in breast milk recognized for their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. LF has gained particular attention for its potential effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 due to its dual mechanism of action [

51,

52].

Our investigation of LF levels in the breast milk of mothers exposed to SARS-CoV-2 or vaccinated revealed its critical role in enhancing passive immunity for infants, thereby offering protection against infections, including COVID-19. This was evidenced by a direct correlation and a significant difference in LF levels relative to the mother’s infection or vaccination status. LF levels were found to be elevated in the breast milk of both vaccinated and, to a greater extent, infected mothers compared to the control group.

In our study, higher levels of LF were also associated with the presence of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in the serum of participants. The increased LF levels in immunized mothers reflect heightened immune activation, antimicrobial defense mechanisms, and an adaptive response aimed at enhancing protection for both the mother and the nursing infant through breast milk. This rise in LF levels observed by us can be attributed to various immunological and physiological factors. Following vaccination, especially against viral pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, there is an elevated production of immune components, including LF. As an acute-phase protein with antimicrobial properties, LF levels surge in response to immune activation, providing enhanced protection to both the mother and the breastfeeding infant. Vaccination has been shown to modify the composition of breast milk by increasing immune factors that support the infant’s immunity [

53]. Additionally, LF plays a crucial role in anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities, contributing to immune regulation and maintaining homeostasis [

16]. This increase in LF provides passive immunity to the infant, offering an additional layer of protection. Elevated LF levels likely reflect the maternal immune response aimed at transferring enhanced protection to the infant, especially against viral infections such as COVID-19 [

54,

55].

The findings of the present study suggested that LD levels in breast milk may help shield infants from infections, including COVID-19. These findings were supported by direct correlations and significant differences in LD concentrations based on the mother’s infection or vaccination status, with higher levels observed in the breast milk of both vaccinated and infected mothers compared to the control group.

Additionally, the ROC curve analysis revealed that, in this study, LD was the most effective predictor of infection status in our cohort. Elevated LD levels, surpassing the cutoff value derived from ROC analysis sensitivity and specificity, were indicative of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the study group.

Our analysis also showed a correlation between LD levels and the severity of maternal symptoms. Higher concentrations of LD were associated with more severe symptoms, suggesting that elevated LD levels reflect the body’s response to a more significant immune challenge. This increase in LD may serve to modulate inflammation and provide additional protection against pathogens [

56]. LD levels are known to rise during inflammatory conditions, where it facilitates the clearance of apoptotic cells, thereby reducing excessive inflammation [

16].

Severe symptoms are typically linked to a higher viral load or more intense infection, prompting the body to upregulate LD production as a protective measure. This increase in LD production may enhance the antimicrobial defense provided to the infant, especially when the mother is facing a severe infection. Studies have documented the antimicrobial role of LD, demonstrating its ability to block viral entry by binding to viral particles [

53].

In previous research, we have observed that severe symptoms often coincide with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 [

57]. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that LD expression is upregulated in response to these inflammatory cytokines, which aligns with its function in resolving inflammation and facilitating tissue repair [

55]. During severe infections, the maternal immune system adapts to protect both the mother and the infant, potentially increasing the concentration of immune factors like LD in breast milk to enhance the infant’s passive immunity [

58].

An important observation in our study was the significant reduction in LF and LD concentrations during the second sampling in both vaccinated and infected mothers. This decrease suggests a trend of normalization following the resolution of viral or post-vaccination effects, further supporting the dynamic nature of immune responses in breast milk.

TC is an extracellular matrix protein that plays a crucial role in tissue repair and immune regulation [

58,

59,

60]. In the present study, TC levels were found to be directly correlated with inflammation, as indicated by IL-6 levels. As inflammation increased, so did TC concentrations, suggesting its role in protecting infants from COVID-19 through breast milk.

Our statistical analysis demonstrated that GB levels were directly correlated with the anti-inflammatory response; as IL-6 levels increased, GB concentrations also rose. This finding supports the known anti-inflammatory effects of GB [

61,

62,

63,

64], which were evident in our study cohort. Although GB was present in the breast milk at significantly lower concentrations than standard serum levels, its correlation with IL-6 suggests that it may contribute to anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial protection in breastfeeding infants [

61,

62,

63,

64].

Understanding the roles of chitin and chitinase-like proteins is essential for advancing disease prevention and treatment strategies, particularly in the context of COVID-19. In our study, C3-1 levels in breast milk were significantly higher than the standard serum values provided by the kit manufacturer, with most volunteers exhibiting elevated levels. However, despite these elevated concentrations, no significant differences in C3-1 levels were observed in relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination status. The absence of significant variation within the study group limits our ability to definitively assess the role of C3-1 in maternal immune activation and its potential impact on inflammatory processes [

65,

66,

67,

68] in breastfeeding infants during infection or vaccination.

F is an enzyme that plays a critical role in activating certain viral proteins [

69,

70], including the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 [

71,

72]. Additionally, host cell F is involved in the activation of various bacterial toxins, such as those produced by

Bacillus anthracis [

73,

74],

Corynebacterium diphtheriae [

74],

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

75], Shiga toxins [

75], and the dermonecrotic toxins of

Bordetella species [

76,

77].

Although F levels in our study group were significantly lower than the standard serum values, F activity was found to be associated with the inflammatory response, as F concentrations increased in tandem with IL-6 levels. Furthermore, the ROC analysis suggested that F levels could serve as a predictive marker for immunization or infection status. This reinforces the understanding of F’s antimicrobial role during lactation, providing valuable insight into the viral defense mechanisms in breastfed infants.

F was a useful predictor of the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in breast milk in our study, owing to its involvement in viral protein processing, immune activation, enhanced antigen presentation, and its correlation with inflammatory responses. This underscored the interrelated roles of proteases and antibodies in the maternal immune response. During infection or after vaccination, F activity is upregulated as it plays a crucial role in cleaving the viral spike protein, facilitating viral entry, and triggering an immune response. The increased presence of F in our research might indicate an active immune process, which corresponded with the production of specific antibodies, such as IgG, against SARS-CoV-2.

Elevated F activity may enhance antigen processing, thereby stimulating a more robust humoral response and promoting the generation of IgG antibodies. This connection may explain why higher levels of F are predictive of the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG in breast milk [

78,

79]. In the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination, the maternal immune system intensifies its defense mechanisms, including the production of proteases like F. Elevated levels of F may thus serve as an indicator of an enhanced immune state, aligning with the production of specific antibodies against the virus. This association likely reflects a coordinated immune response, wherein F expression is part of the broader activation of the immune system that leads to the generation of IgG antibodies [

80].

Additionally, in our study, F levels were correlated with pro-inflammatory markers in our study, which were elevated during infection or post-vaccination. Given that inflammation can promote immune activation and antibody production, higher F concentrations may reflect an underlying immune process that also contributes to increased IgG levels in breast milk [

55].

In our research, the concentrations of C3-1 and F in breast milk were found to vary with maternal parity, with levels decreasing as the number of births increased. Specifically, the excretion of F and C3-1 in breast milk was higher in mothers with firstborns. The observed decrease in C3-1 and F levels with increasing maternal parity may be linked to immune and physiological adaptations that occur with subsequent pregnancies and births. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that first pregnancies often involve a stronger immune response as the maternal immune system encounters fetal antigens for the first time. As a result of our analysis, primiparous mothers tended to experience heightened inflammatory and immune responses compared to multigravida women, which may explain the observed variations in immune-modulating proteins in breast milk across different pregnancies [

81,

82].

Following the first pregnancy and childbirth, the mother’s mammary glands undergo structural transformations, including tissue remodeling, which has been associated with the production of proteins such as C3-1. These proteins contribute to tissue repair and immune modulation. In subsequent pregnancies, the need for such intense tissue adaptation may diminish, leading to lower levels of remodeling-related proteins [

83,

84,

85].

Research has indicated that firstborns may receive breast milk with higher concentrations of immune-modulating proteins, potentially reflecting the mother’s initial investment in supporting neonatal immunity [

16,

86,

87].

In our study, variations in C3-1 levels were observed based on the mode of delivery, with mothers who underwent vaginal delivery showing lower concentrations of C3-1 in their breast milk compared to those who had a cesarean section. This difference may be attributed to the distinct inflammatory responses associated with natural versus cesarean deliveries. Cesarean sections generally involve greater surgical stress and immune activation, which can trigger a more pronounced inflammatory response when compared to vaginal deliveries. This increased inflammation could elevate the levels of certain immune-related proteins, including C3-1, known for its involvement in inflammation and immune modulation [

67].

Furthermore, C3-1 is frequently associated with wound healing and tissue repair, processes that are more prominent following cesarean delivery. The body may produce higher levels of C3-1 to support recovery and manage the heightened inflammatory response induced by the surgery. This could help explain why mothers who undergo cesarean sections might have increased concentrations of C3-1 in their breast milk [

67].

The correlation between C3-1, F, LD, and TC levels in the breast milk of our mothers and the age of the infant can be attributed to several factors related to the infant’s evolving nutritional and immunological needs. These findings align with the broader understanding that breast milk undergoes dynamic changes in its bioactive composition, adapting to the infant’s developmental stages and providing tailored support to meet the infant’s shifting physiological demands.

The composition of breast milk undergoes dynamic changes to meet the evolving developmental needs of the infant. In our study, the observed increase in concentrations of C3-1, F, LD, and TC in breast milk as the infant aged can be attributed to several factors related to the infant’s maturing immune system and ongoing maternal physiological adaptations. These findings underscore the dynamic nature of breast milk and its role in adapting to the infant’s changing developmental and immunological requirements. The increase in these specific proteins reflects a maternal strategy designed to continue providing enhanced protection and support as the infant progresses through various stages of early life.

As infants grow, their immune system gradually matures, although it remains in a transitional phase for an extended period. During this phase, the demand for immune-modulatory and protective factors in breast milk may intensify. Proteins such as C3-1, F, LD, and TC may be upregulated to offer continued protection as the infant encounters more environmental pathogens and dietary antigens, particularly with the introduction of solid foods. This adjustment aligns with the adaptive function of breast milk in responding to the infant’s exposure to new antigens and microorganisms [

16].

Breast milk composition is not static; it adjusts in response to both maternal and infant health changes. The prolonged lactation phase may induce sustained maternal immune adaptations, leading to the increased secretion of immune-related proteins, including F and TC, which contribute to antimicrobial defenses. This ongoing maternal response becomes more pronounced as the infant ages, representing an adaptive mechanism to enhance protection against greater pathogen exposure during later infancy [

84,

85].

As infants grow older and gain more mobility, their exposure to various pathogens increases, highlighting the importance of enhanced immune protection. Elevated levels of bioactive proteins in breast milk may serve as a protective response by the mother, bolstering the infant’s immune system. For example, increased levels of LD have been associated with enhanced antimicrobial properties, while TC and C3-1 are linked to anti-inflammatory responses, which become increasingly critical as the infant’s exposure to infectious agents rises [

87,

88].

As the infant’s nutritional and developmental requirements change, the concentrations of specific bioactive components in breast milk may adjust accordingly. Proteins such as F and C3-1, involved in tissue repair and growth, are particularly important during periods of rapid development. Therefore, the increased levels of these proteins may reflect a maternal adaptation to support the infant’s ongoing growth needs [

85,

88].

Other comparisons made by us revealed that maternal vaccination may influence the immune composition of breast milk differently from natural infection. Understanding these differences is critical for evaluating how breastfeeding mothers provide passive immunity and guiding recommendations on maternal vaccination during breastfeeding to optimize infant health.

Breastfeeding remains a vital means of transferring immunity from mother to child, particularly for infants with developing immune systems. Our study identifies specific proteins such as TC, GB, and C3-1, which provide insight into how maternal COVID-19 infection or vaccination affects immune protection conferred to the infant. The long-term health outcomes of infants born during the COVID-19 pandemic are still being studied, but determining the presence and role of these immune factors in breast milk offers valuable information on how early exposure to maternal antibodies and immune proteins shapes infant immunity and development.

Our study identified differences in lactoferrin and lactadherin levels between vaccinated mothers and those who had been infected. Additionally, variations in furin levels were observed between both infected and vaccinated mothers compared to the control group. Furthermore, chitinase 3-like 1 levels were elevated in mothers who delivered via cesarean section, while primiparous mothers exhibited higher levels of both furin and chitinase 3-like 1 (

Table 11). All other unmentioned variables did not show statistically significant differences between the analyzed groups.

Our findings have significant implications for public health recommendations regarding breastfeeding practices during the pandemic and post-vaccination. The elevated immune components observed after vaccination support the promotion of vaccination among breastfeeding mothers, as it may enhance infant protection. Furthermore, these findings provide reassurance about the safety and benefits of continuing breastfeeding during maternal infection with SARS-CoV-2.