The mayor of Urania steered his pickup down a dirt road snaking through the weedy lots and patches of trees that had once been the bustling heart of his central Louisiana town.

Jay Ivy passed pines growing where the saws of the sprawling Urania mill turned similar specimens into lumber. He pointed out the log pond, now the domain of alligators, and stopped at the mill’s smokestack, still standing over an increasingly deserted townscape. Once a year, the smokestack belches celebratory black clouds over Urania.

“For our fall festival, we get it smoking again with some old tires or whatever we can find to burn,” the big-shouldered mayor said with a sheepish grin. “I suppose it reminds us of what we had here.”

Urania was devastated when the mill and a related fiberboard operation closed in 2002, putting more than 350 people out of work. There was little hope of a revival until the British energy giant Drax arrived in the Deep South a decade ago, hungry for cheap wood it could burn in England as a “renewable” alternative to coal.

Drax began opening wood pellet mills in former timber towns in Louisiana and Mississippi that had fallen on hard times. The region offered plentiful low-grade timber, a labor force desperate for work, and lax environmental regulations. The company was already producing pellets, which it calls “sustainable biomass,” in Mississippi and north Louisiana when Drax opened its biggest pellet mill just outside Urania in late 2017.

A ‘Welcome to Urania’ sign, stands at the entrance of the small Louisiana town, home to a Drax wood pellet mill. At the mill, LaSalle BioEnergy, logs await the grinders. Eric J. Shelton / Mississippi Today

A year later, then-Louisiana governor John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, thanked Drax for “believing in Louisiana.” Jobs and other economic growth were soon to follow, he and the company promised. “Louisiana aggressively pursued Drax Biomass and today those efforts have paid off,” Edwards said at the time.

But more than a decade after Drax took root in the region, prosperity has yet to arrive. Drax employs a fraction of the workers the old mills did, and many commute from other towns. The money that might have flowed from Drax into investments in local roads, parks, and schools has been eroded by massive tax breaks.

Now home to around 700 residents, Urania has lost nearly half its population since 2010, a decline that continued after Drax built its mill in 2017. In 2023, it drew unwanted attention when a news site declared it “the poorest town in America.” According to the most recent census report, some 40 percent of Urania’s residents live in poverty, and the average income is $12,400 — roughly one-fifth the national average.

“It’s a town of old people — a poor town, really,” Ivy said.

Gloster, Mississippi, a majority Black town of about 850 people near the Louisiana line, has also seen its population shrink since Drax opened a pellet mill near the shuttered elementary school in 2014. More than 10 percent of Gloster’s working-age residents are unemployed, and the typical household income of about $22,500 is less than half the Mississippi median.

Residents in both towns believe that noise, dust, and air pollution from the nearly identical mills are harming their health. While it remains unclear whether Drax’s operations can be tied to any one person’s illness, the mills release chemicals at concentrations that federal regulators and scientists say are toxic to humans. Louisiana and Mississippi state regulators have repeatedly fined the company for a host of pollution violations, but several residents and environmental groups say the penalties haven’t made a noticeable difference.

“Drax is a false solution,” said Jimmy Brown, a former worker at Gloster’s plywood mill, which closed 17 years ago. “They want to make something they can’t make in their own country, so they come here. We got this mill, but we don’t have schools anymore. We don’t have doctors anymore, and we got all these people with respiratory issues and heart issues now.”

On the outskirts of Urania, a giant hydraulic arm tips a tractor-trailer backward until its cab points to the sky. Several tons of tree limbs and other logging debris spill from the trailer into one of the mouths feeding Drax’s mill, called LaSalle BioEnergy.

The half-mile-long facility also consumes a steady diet of sawdust from a neighboring lumber mill and a huge volume of tree-length logs, hoisted by crane into the teeth of an industrial-size wood chipper.

“We take everything — the little bitty trees that’re so thin that nobody wants them, and also the limbs and even the pine needles,” Tommy Barbo, the mill’s manager, said during a tour. “Nothing gets wasted.”

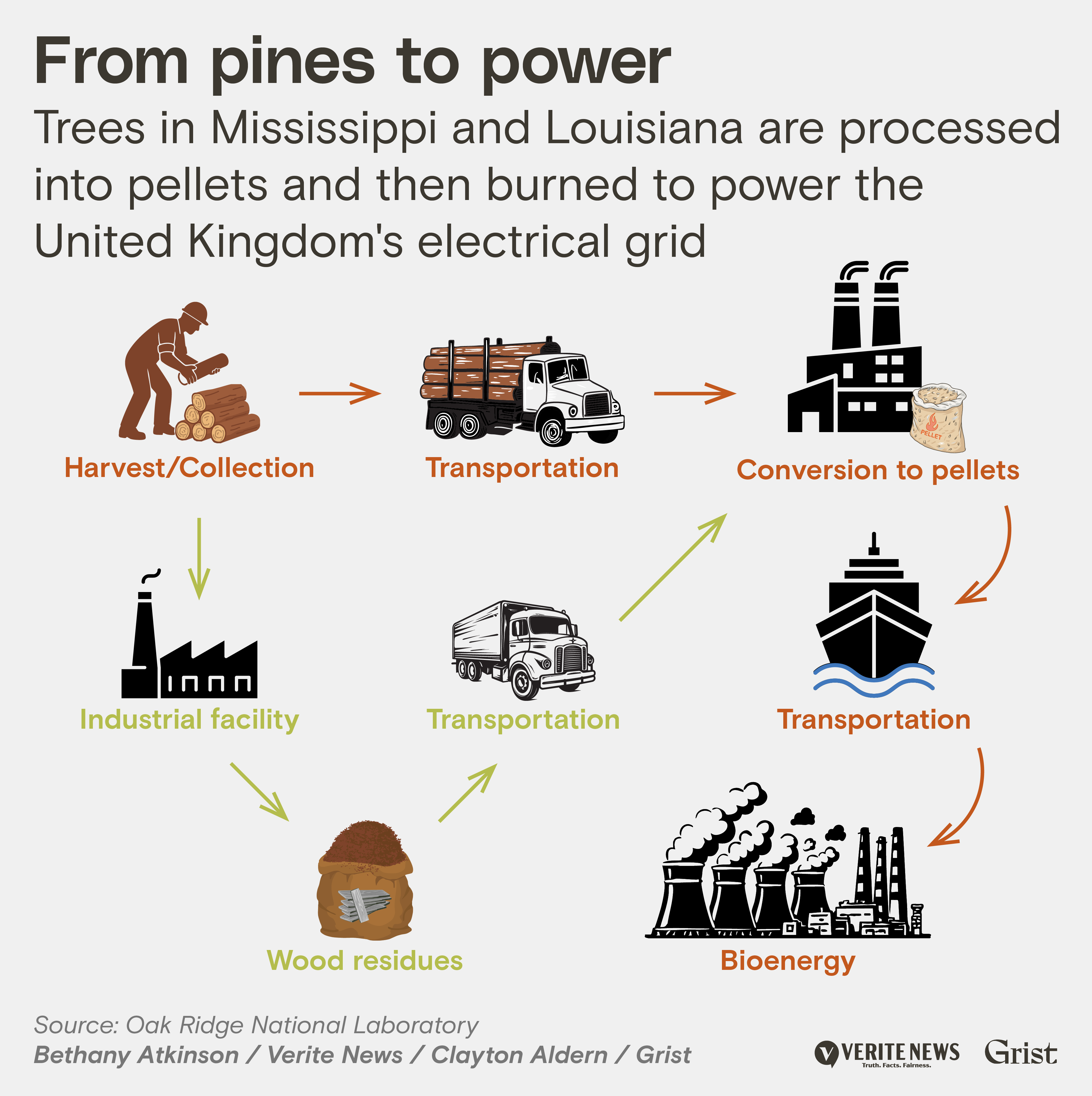

Drax and other utility-scale pellet makers initially promoted their industry as consumers of sawdust and other mill wastes, but these sources couldn’t meet their growing production goals. Large pellet mills now get most of their wood directly from logging whole trees.

At the Urania mill, log stacks larger than football fields and higher than houses are stripped of bark, shredded, cooked in a 1,000-degree tumble dryer, pulverized in hammermills, pressed into pellets and loaded on trains bound for Baton Rouge. From there, the pellets are shipped nearly 8,000 miles — through the Gulf of Mexico and across the Atlantic Ocean to northeast England.

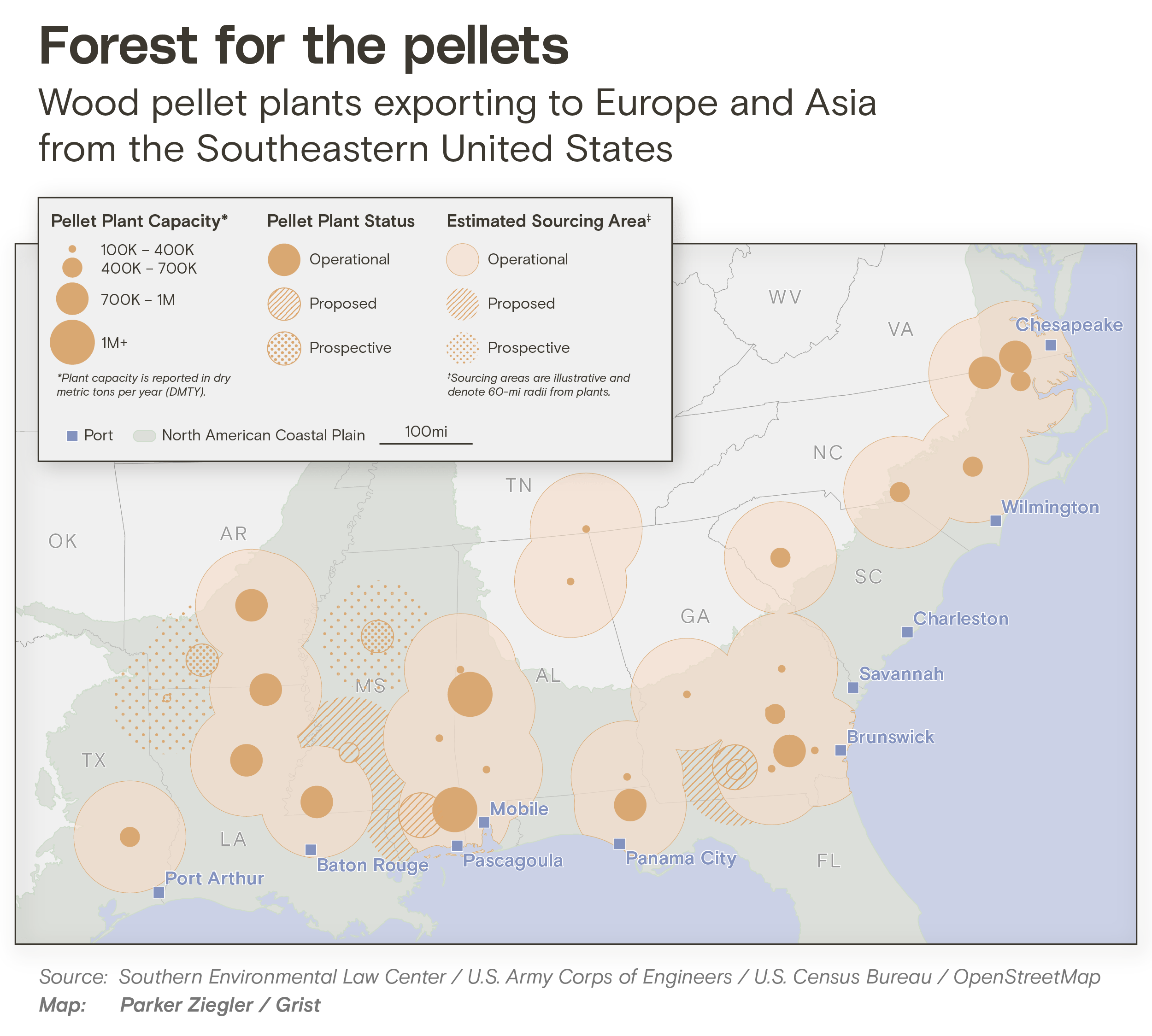

Drax is riding high on explosive global demand for pellets, record profits, and government subsidies. Pellet exports from the U.S. have quintupled, growing from 2 million tons in 2012 to about 11 million tons in 2024, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. An increasing share of those exports has come from the South, reaching about 85 percent in 2023.

Including Drax’s five facilities in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, there are 30 large pellet mills across the region and at least four more are proposed. Enviva, one of the industry’s biggest players, was building the world’s largest-capacity pellet plant in Epes, Alabama, when it declared bankruptcy in early 2024. The Maryland-based company had no trouble finding buyers for its pellets. Enviva’s troubles arose when it failed to produce pellets in the quantities and prices it had promised. Enviva shuttered its mill in Amory, Mississippi, last year but still has a presence in the state, producing pellets in Lucedale and shipping from its terminal at the Port of Pascagoula.

Much of the pellet industry’s growth was driven by the European Union’s decision in 2009 to classify wood burning as a renewable energy source on par with solar and wind, making it eligible for subsidies, low-interest loans and other government incentives. By the end of 2027, when Drax’s current subsidy support is scheduled to run out, the company will have received more than $14 billion in subsidies from the U.K. government, according to the climate think tank Ember.

Louisiana has also been generous to the company. Drax’s two mills in the state, which employ about 140 workers, have been exempted from paying about $75 million in property taxes via the state’s Industrial Tax Exemption Program, known as ITEP, Verite News and Grist found in a review of estimates from Louisiana Economic Development, a state agency. Aimed at attracting jobs and economic activity, the tax-exemption program shields large companies from taxes that would otherwise help support school districts, police departments, and other local government operations.

Mississippi offered Drax $2.8 million in grants and more than $1.5 million in tax breaks to draw the company to Gloster.

While benefiting from taxpayer largesse, Drax has also seen its earnings climb. The company’s profits rose from nearly $1.3 billion in 2023 to about $1.4 billion in 2024.

Tommy Barbo inspects wood pellets produced at the mill in Urania. The pellets are shipped to England to be burned in a former coal power station. Eric J. Shelton / Mississippi Today

Drax recently expanded a mill in Alabama and brokered an investment and supply partnership with a company planning to build a jet fuel plant at a yet-to-be-determined location on the Gulf Coast. Drax also established a North American headquarters in Monroe, Louisiana, and opened an office in Houston to lead its carbon-capture enterprises.

For Barbo, the global pellet boom means he feels compelled to check second-by-second production stats to make sure he’s meeting demand. “Even when I’m home, I’m checking all this on my phone,” he said.

Over the past seven years, the mill in Urania has produced enough pellets to fill the New Orleans Superdome nearly two times. Barbo is proud that his mill is the company’s top producer in the U.S., and he aims to keep it that way. “We did 377 tons this morning,” he said. “We try to keep it on pace at 95.2 tons an hour. Pretty good so far.”

Mayor Ivy radiates pride when talking about Urania’s founder and all his mill provided. Henry Hardtner, a lumber baron who named both his land and business Urania, created a closed-loop company town. Most houses and stores were provided by Hardtner’s company. In one big building called the commissary, residents could find groceries, medicine, clothes, tools, a post office, and a soda fountain.

“You’d spend your whole paycheck there using the company’s own money,” Ivy said, referring to mill tokens that were worthless beyond the town’s limits.

Hardtner had a monopoly on almost every facet of town life, but he offered stability, security, and enough jobs to support hundreds of families. The leaders of many small, remote mill towns like Urania and Gloster still believe their communities can’t thrive without a large industrial facility, whether it be a mill, factory, or chemical plant.

“All of these small towns, we have nothing,” Gloster Mayor Jerry Norwood said. “If big business don’t commit the big dollars, we don’t have the tax base. We have to have that for community growth.”

A larger tax base is the “lifeline” Drax offers to dying towns with dying industries, wrote Jessica Marcus, Drax’s North American head of public affairs and policy, in an opinion piece posted on the company’s website. “Particularly in hard-hit states across the U.S. South like Mississippi and Alabama, communities are looking for other reliable sources of income to provide a dependable path back to prosperity.”

Drax estimates that its annual “economic impact” from taxes and wages exceeds $150 million in Gloster and the surrounding area and close to $200 million around Urania. The company is a frequent donor to community groups, providing funds to replace the floor in a Urania school gym and to install a new air-conditioning system at a Gloster meeting hall. The company has also given away turkeys at Thanksgiving and helped stock local food banks.

Drax reported $907,000 in charitable giving in the U.S. in 2024, mostly focused on five Southern states. The company is more generous in its home country, giving away three times as much — about $3.3 million — to U.K.-based nonprofits and schools.

To Krystal Martin, the founder of the Greater Greener Gloster community group, these giveaways are a relatively cheap way for the company to build goodwill where it’s doing the most harm.

According to state regulators in Louisiana and Mississippi, Drax’s mills have repeatedly exceeded their pollution limits, releasing harmful levels of formaldehyde, methanol, and other chemicals that can cause cancer, damage brains, and harm lungs. Despite millions of dollars in fines and promises to improve, many residents — especially in Gloster — say their health is declining.

“They sell you hopes and dreams, but they don’t tell you the stuff they’re producing will make you die,” Martin said.

Bearing environmental dangers might be worthwhile if the company offered more jobs, residents in Urania and Gloster said. But Drax’s employment opportunities have fallen far below many people’s expectations. Each of the three Drax mills in Louisiana and Mississippi employs between 70 and 80 people. That’s a fraction of the hundreds working in mills in each town 20 years ago. In Gloster, most of Drax’s employees live outside town, beyond the reach of the mill’s noise and pollution. According to the company, only 15 percent of employees reside in Gloster.

The Urania Lumber Co. had at least 350 workers when it shut down in 2002. The International Paper mill in Bastrop, Louisiana — near Drax’s Morehouse BioEnergy mill — employed more than 1,100 people during the early 2000s and about 550 workers just before it closed in 2008.

In Gloster, the Georgia Pacific mill provided about 400 “good-paying, union jobs” until it closed in 2008, said Brown, who worked at the plywood mill for 24 years. Once it closed, many basic services evaporated, including schools and grocery stores. Without a doctor in town, Gloster residents with heart and respiratory ailments now must drive nearly an hour to McComb or two hours to Jackson for treatment.

After losing his job at Georgia Pacific, Sammy Jackson bounced around the Louisiana oil fields and worked as a security guard in Texas. He was quick to apply for a job with Drax’s Gloster mill. “They said they wanted to hire a lot of local people,” Jackson said. “Everybody was excited.”

He was one of hundreds who took a test required for employment. While everybody seemed to do well, Jackson was one of the few to get an offer. But it wasn’t Drax that hired him — it was a temporary labor agency that paid him $11 per hour to do cleanup work, mostly shoveling ashes and wood dust. He didn’t mind the sweat or long hours, but the conditions didn’t seem safe, with ash and dust coating everything, he said.

“Man, that shit would get in your eyes and on your skin, and it’d be burning and itching,” Jackson said.

In the oil business, Jackson had been supplied respirator kits and protective clothing for dirty jobs, but the gear provided at the mill was far more basic. “Just safety glasses and a surgical mask,” he said. “I wasn’t feeling right. Had a real dry cough all the time when I was working there. People’d be asking me, ‘What’s wrong with you?’”

A Drax spokesperson couldn’t directly address Jackson’s experiences but said the company “maintains robust safety standards and contractor requirements.”

“We take all health and safety concerns seriously,” the spokesperson said. “We also have extensive and ongoing training requirements in place to ensure the safety of our employees.”

Mabel Williams, a lifelong resident of Gloster, said she never wanted a job at Drax, but once had high hopes that the mill would employ enough people to breathe life back into downtown. During a walk along Main Street, the 87-year-old didn’t see another soul, though her memories crowded every empty lot and darkened window.

“There were people everywhere,” said Williams, who spent decades cleaning the homes of the white residents who mostly moved away. “This was a clothing store and that was a jewelry store owned by a German man. And over there, my mama worked at the cafe.” Across the train tracks was the Black business district, with four barbershops, restaurants, and music venues.

All the buildings Williams points out are vacant or partially collapsed, but she slaps her thigh and smiles. “I get excited when I think about what Gloster had,” she said. Williams still has faith that Gloster is capable of a revival. She just doubts that it will be thanks to Drax. Despite the billions in profits, little of the company’s wealth is trickling down to Gloster, she said.

“Drax is making so much money. They’ve got to spend that money some kind of way, but they’re not spending it here.”

Source link

Tristan Baurick grist.org