1. Introduction

The development of modern navigation, in particular the determination of optimal routes for ships, has long attracted the attention of researchers and practitioners in the field of maritime transport. Contemporary navigation faces challenges arising from the increasing number of ships on the seas and oceans, the growing demand for efficient maritime transport, and the increasingly complex aspects related to safety at sea and environmental protection. In response to these challenges, scientists and engineers have developed methods and algorithms to effectively determine ship passage routes, taking into account a range of factors such as weather conditions, the movement of other vessels, water depth and environmental constraints.

There are three main types of algorithms, and their various variations, that can be found in the contemporary literature related to the determination of ship passage routes. These include genetic algorithms, graph search algorithms and swarm algorithms.

Genetic algorithms are inspired by biological processes and include concepts such as natural selection, recombination and mutation. When analyzing the literature related to this type of algorithm, several primary applications can be distinguished:

- Finding a safe route in areas with limited maneuverability: An example of using a genetic algorithm to determine a route between islands and reefs is presented in [4]. The authors of this publication found that traditional algorithms, such as ant colony algorithms, did not perform well in this context, so they proposed their own algorithm using environmental information. Another approach to determining a ship’s route in restricted waters was presented by the authors of [5]. They focused on a parallel genetic algorithm, and additionally, considered criteria related to water depth and travel time.

- Determining routes where the criteria include minimizing energy consumption, travel time, etc.: This type of approach was taken by the authors of publications [6,7]. They presented an algorithm using elements of particle swarm optimization and genetic algorithms to determine the route. This approach successfully optimized fuel consumption.

- Determination of collision avoidance routes: This category includes publications that do not directly address the determination of a route from a starting point to an end point, but instead present algorithms that adapt local segments of the route to the new conditions surrounding the ship, for example, to perform a collision avoidance maneuver. Examples of publications related to this type of algorithm are [8,9,10]. The authors presented different approaches to collision avoidance maneuvers, ranging from harbor operations to applications related to autonomous vehicles.

The final type of algorithm that is most commonly used to determine ship passage routes are swarm algorithms. Swarm algorithms are a category of optimization techniques inspired by the social behavior of animals such as insects, birds or fish. In nature, animals often interact in groups, forming swarms, flocks and schools, and their coordinated actions can lead to the solution of complex problems. Swarm algorithms include the following:

Ant colony algorithms: These are inspired by how ants find the shortest path to a food source. In ant colony algorithms, agents (virtual ants) explore the solution space and leave pheromone trails that guide other ants to optimal solutions.

Particle swarm algorithms: These are based on the behavior of schools of fish or flocks of birds. In particle swarm algorithms, particles (points in the solution space) move through the search space, guided by their own experience and information from other particles, to find an optimal solution.

Bee-inspired algorithms: These algorithms mimic the behavior of bees foraging for food, where bees identify the best food sources and recruit other bees to exploit those sources.

Firefly algorithms: The main principle of operation is the attraction of fireflies based on their brightness, which represents the quality of a given solution to the problem. The brighter the firefly (the better the solution), the greater the attraction it exerts on other fireflies. The brightness of a firefly depends on the objective function and decreases with distance: fireflies closer together are more attracted than those further apart. Fireflies with lower brightness move towards brighter ones, meaning that the algorithm iteratively improves its solution.

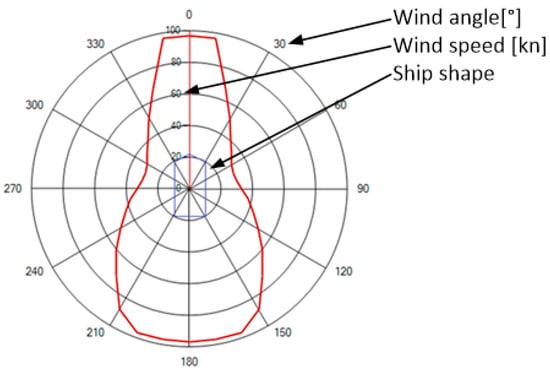

This paper demonstrates the use of a modified version of Dijkstra’s algorithm and position-keeping Capability Plots (CP) to determine a passage route that minimizes the impact of environmental forces on the ship’s hull, thereby reducing energy consumption. This method has been developed for autonomous vessels equipped with a positioning system based on a set of anchors. For such vessels, the challenge is to move from the starting point to the pre-planned anchorage area. As the thrusters are not involved in the positioning operation, their power is significantly lower than the thrusters used in Dynamic Positioning (DP) systems, resulting in reduced maneuverability. For this reason, the ship’s passage route should be chosen in such a way as to minimize the influence of disturbance factors. The verification of the presented algorithm was carried out using a simulator developed in the Unity3D environment.

3. Route Determination for Ship Passage Using Capability Plots

The determination of a vessel’s route between two geographical points (the starting and ending points of the route) is one of the initial tasks in planning any maritime operation, for example as an anchoring operation at an anchorage site. Vessels designated to keep their position at anchor are typically equipped with thruster systems that are considerably less powerful than those on vessels equipped with a DP system. This difference means that in higher wind speeds, they cannot maneuver freely using only their thrusters, resulting in increased energy consumption and a prolonged travel time along the route. To minimize the impact of environmental forces on the vessel’s hull and thereby reduce the energy consumption, the use of the vessel’s CP and Dijkstra’s algorithm can be advantageous.

3.1. The Concept of the Algorithm

The diagram above includes two points: A, the starting point, and B, the endpoint. It is assumed that the designated passage route should end at the location of the first anchor drop. The distance between the points is 2.4 NM.

When preparing the anchoring operation, the ship’s crew arrives at the designated anchorage area and makes a preliminary assessment before analyzing anchor placement and maneuvering strategies. For this reason, the presented algorithm starts to determine the route from the point closest to the ship’s current position.

For the purpose of demonstrating the algorithm’s function, a waypoint density of 10 was assumed, resulting in a matrix where each row and column contains 11 points (with numbering starting from 0). It was also assumed that the wind speed acting on the ship is 10 m/s, with a direction of 20°.

The considered case of route determination is a classic graph search problem. One of the popular methods for solving such problems is the use of Dijkstra’s algorithm. Dijkstra’s algorithm finds the shortest path between two vertices in a weighted graph, where edges are assigned numerical values known as weights. As a greedy algorithm, Dijkstra’s approach makes locally optimal choices at each stage, leading to a globally optimal solution. However, for the algorithm to function correctly, the graph must not contain edges with negative weights.

where Fα(α)—resultant environmental force currently acting on the ship’s hull at angle α; Fmax—maximum resultant environmental force that can act on the ship’s hull.

[number of waypoints × number of waypoints]

The table should be interpreted as follows:

Starting from point 0 (row 0), the transition cost to point 1 is 0.3095, to point 11 is 0.0533 and to point 12 is 0.1937. The transition cost to all other points is 10, as there is no connection between point 0 and those points. The transition cost from point 0 to itself is also 0.

| Algorithm 1: Dijkstra algorithm |

| def dijkstra(graph, start): # Initialization of weights to all vertices as 10 distances = {vertex: 10 for vertex in graph} # Weight to itself set to 0 distances[start] = 0 # Initialization of the priority queue priority_queue = [(0, start)] while priority_queue: # Skip if the current sum of weights is bigger # Iteration over the neighbors of the current vertex # Updating the sum of weights if a shorter path is found return distances |

3.2. Ship Route Without Using the Algorithm

where T—route cost function [-]; n—number of transitions between waypoints [-]; i—current transition between waypoints [-]; d—distance between waypoints January; k—cost of transition between waypoints [-]

In the table above:

Phase—current route segment.

S—distance between points.

V—speed of the ship.

t—the duration of the navigation of the given segment.

Course—ship’s course.

True wind angle—angle of wind impact on the vessel.

Env. Force vector—environmental forces affecting the vessel over a given distance.

Sum of thrust—thrust generated by propellers.

Fuel consumption—fuel consumption per route section.

Energy consumption—energy consumption per route section.

3.3. Route Determined Using Dijkstra’s Algorithm and the Capability Plot

The cumulative weight of transitions for the identified route is 0.8476, which is the lowest value obtainable given the parameters of the anchorage. It is possible to find alternative routes that yield the same sum, however, from the algorithm’s operational perspective, there is no difference between them.

For the route determined by the algorithm, the value of the route cost function was 747, approximately 13% lower than when the ship travels directly to the endpoint.

The energy consumption for the route determined by the algorithm was 4231.127 [kWh], which is 7.58% less than the direct route to the end point.

3.4. Other Examples of Determined Routes

The algorithm presented in the publication can be used to determine routes for different hydrometeorological conditions. Below are some examples of routes determined, together with information on the specific weather conditions for which they were generated.

3.4.1. Navigation Scenario #1

wind speed: 25 m/s.

true wind direction: 350°.

sea current speed: 1 m/s.

true sea current direction: 20°.

During the route directly to the destination, energy consumption was 5062.43 [kWh].

The energy consumption analysis showed that the energy consumption for the route determined by the algorithm was 4848.06 [kWh], 6.36% less than for the direct route to the destination.

3.4.2. Navigation Scenario #2

wind speed: 25 m/s.

true wind direction: 90°.

sea current speed: 1 m/s.

true sea current direction: 20°.

The cost of the route function for the first scenario, when the ship travels straight to the destination, is about 1131, which is approximately about 4.8% more than for the route determined by the algorithm.

During the route directly to the destination, energy consumption was 5773.44 [kWh].

In Scenario 2, the energy consumption for the route determined by the algorithm was 5426.18 kWh, resulting in a 6% reduction in energy consumption compared to the direct route.

3.4.3. Navigation Scenario #3

wind speed: 10 m/s.

true wind direction: 75°.

sea current speed: 0.5 m/s.

true sea current direction: 20°.

The cost of the route function for the first scenario, when the ship travels straight to the destination, is about 598, which is approximately about 12.4% more than for the route determined by the algorithm.

During the route directly to the destination, energy consumption was 3174.81 [kWh].

In Scenario 3, the energy consumption for the route determined by the algorithm was 2642.28 kWh, resulting in a 16.7% reduction in energy consumption compared to the direct route.

4. Discussion

The ship’s capability plot must be available. As mentioned in the publication, any DP 2 or higher vessel is required to have it, but if the route is being determined for a DP 1 vessel or one without such a system, the capability plot would need to be calculated independently.

If the route needs to be updated during operation, the vessel must monitor wind speed in real time and measure or estimate the speed of the sea current.

The speed of route calculation also depends on the programming language used. The algorithm described in the paper was written in Python and also used as part of code written in C#. Both are high-level languages. If the algorithm were implemented in C or C++, shorter route generation times could be achieved. Currently, the times are as follows: for a 6 × 6 grid—0.05 s, for an 11 × 11 grid—0.36 s, for a 16 × 16 grid—0.47 s, and for a 21 × 21 grid—0.85 s.

This publication also presents a comparison of the ship’s passage routes for two cases: a direct route from the starting point to the end point, and the algorithm-determined route. The comparative analysis showed that along the route determined by the algorithm, environmental forces exerted 13% less stress on the ship’s hull, resulting in a 7.5% reduction in energy consumption. In addition, three other examples of routes determined by algorithm were presented. In two cases, a 6% reduction in energy consumption was achieved compared to the direct route to the destination, and in one case, environmental conditions were found that allowed a route with a 16% reduction in energy consumption.

Theoretically, the presented algorithm has no limitations regarding the maximum length of the determined route, provided that real-time data on wind and ocean currents are available. Unfortunately, during the route determination studies, it was not possible to determine a route beyond a single area of uniform environmental conditions because there was no way to introduce multiple changes in hydrometeorological conditions along the route. It was decided to demonstrate the functionality of the algorithm using the example of a vessel that needs to reach an anchorage. Such vessels do not travel very long distances, so it was possible to consider their entire operational area as one with consistent environmental conditions.

The studies showed that the presented algorithm could be used in the future for autonomous control of vessels that have to anchor according to a pre-planned anchorage layout.

5. Conclusions

The determination of ship passage routes plays a crucial role in maritime management, contributing to improved efficiency, enhanced safety and protection of the marine environment. By properly defining a passage route, it is possible to avoid potentially dangerous areas such as shoals or reefs, significantly reducing the risk of collisions, breakdowns and other incidents that threaten both the crew and the vessel. Routing systems and algorithms should also take into account changing sea conditions, monitoring wind, currents and waves and updating the route as necessary.

This paper presents a method for planning a ship’s passage route using capability plots and an algorithm based on Dijkstra’s algorithm. By using these plots to determine transition weights between points, it was possible to find a route that minimized the impact of wind on the ship’s hull. However, this does not mean that the chosen route meets other criteria such as minimizing travel time or being the shortest route. Nevertheless, for ships that are not equipped with thrusters that allow free movement along any axis, the method presented in the publication will be safer. The proposed route determination algorithm can be used to plan a route while the ship is in port. It can also monitor the ship’s route during navigation, recalibrating the transition weights based on the current environmental conditions and adjusting the route accordingly.

Source link

Jakub Wnorowski www.mdpi.com