As Earth continues to warm, more and more of the planet is becoming dry. A 2024 UN report found that in the last three decades, over three-fourths of all the world’s land became drier than it had been in the previous 30 years.

Drylands now comprise 40.6% of all global land (excluding Antarctica). In addition, the number of people living in drylands doubled over the last 30 years to 2.3 billion, which represents over 25% of the global population. In a worst-case climate change scenario, this number could climb to 5 billion by 2100.

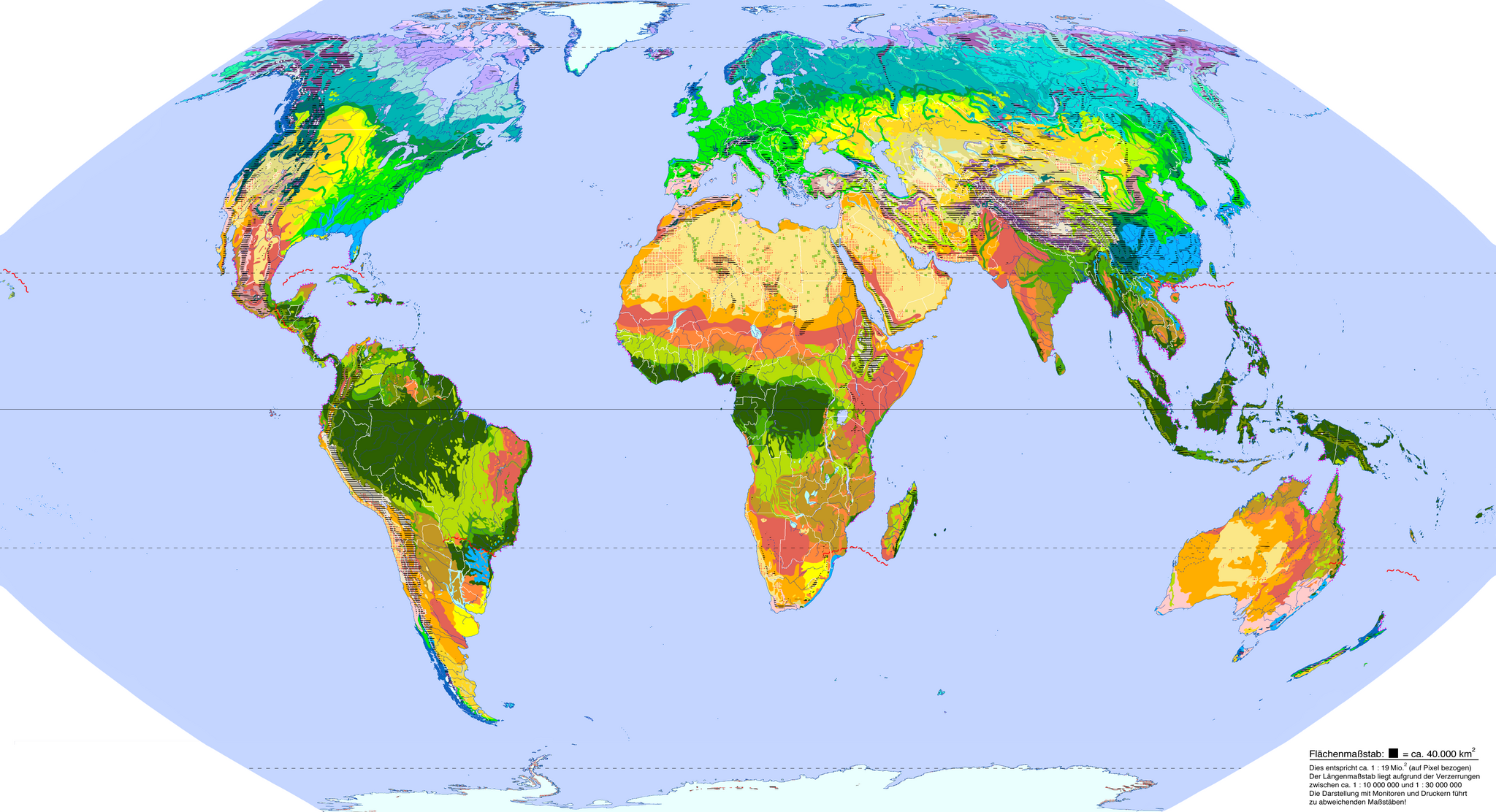

Drying is occurring in many parts of the world, including the western U.S., Brazil, most of Europe, Asia and central Africa. If greenhouse gas emissions continue on their current trajectory, 3% more of the world’s humid areas will become drylands by 2100. Drylands would likely expand in the U.S. Midwest, central Mexico, parts of Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina, the entire Mediterranean area, the Black Sea Coast, and southern Africa and southern Australia. There are no regions of the world that are expected to go from drylands to a more humid climate in the future.

Drought vs. desertification

Desertification occurs when an area’s climate turns drier, and fertile land becomes barren due to factors caused by human activities—mainly climate change and poor land use. Drylands, or areas with limited water and soil moisture like grasslands, savannas and some forests, are at the greatest risk for desertification. When these lands are degraded to the point of infertility, they become desertified. It’s estimated that 25-35% of drylands are already experiencing desertification.

Desertification is distinct from drought. Droughts are temporary periods of less rain—they end. But desertification is a permanent transformation wherein the land cannot return to its former state. “Historically, there has been a lot of confusion about the difference between drought and desertification,” said Michela Biasutti, a climate scientist at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory who has worked in the African Sahel. “The fact that some soil is not productive because you’re in a drought doesn’t mean that the desert has advanced and it will never retreat. That was the fear when an area of the Sahel went into drought in the late ’60s and ’70s. But we’ve learned that that’s not the case. When the rain came back, the grasses did come back.” If there is a drought, she said, you can’t know if the soil is degraded simply because it is not productive. Once the rains return, however, the state of the soil will determine if the land is at risk of desertification.

What causes desertification?

Climate change can lead to drought and dryer conditions. Since 2000, the occurrence of drought has risen 29%, and projections show that by 2050, 75% of all humanity could be affected by drought. When soils do not receive enough moisture to sustain plant life, plants die as well as the soil microbes needed to maintain life cycles, eventually creating desert-like conditions. If the soil is degraded through poor management, these conditions can become permanent.

Unsustainable practices such as overgrazing can cause erosion and degrade land. Every year, 24 billion tons of fertile soil are lost to erosion. Agricultural approaches such as tilling and the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides that kill good microbiota and remove important nutrients can leave the land barren. Deforestation contributes to desertification because without trees, the soil cannot retain moisture. Already 50% of tropical forests in South America, Africa and Southeast Asia have been cut down for cattle ranching or soy and palm oil plantations.

The overextraction of water from aquifers, usually for irrigation, can lead to desertification. A prime example of this is how the over-irrigation of cotton drew too much water from the Aral Sea in Central Asia, once the fourth largest lake in the world, shrinking the lake to one-tenth its size, salinizing the soils, and turning the exposed seabed into the Aralkum Desert.

Population growth and urbanization also contribute to desertification because they put increased pressure on the land’s resources—ecosystems, aquifers, grazing land and agricultural fields near cities. Desertification in turn increases urbanization because people flee to cities when their land is no longer productive.

The effects of desertification

Desertification is both a result of and a cause of erosion of fertile soils, reducing agricultural and livestock productivity. If current land degradation trends continue, crop yields could decline 50% by 2050. Desertification can also reduce the amount of wood available for fuel or construction. These impacts exacerbate poverty and hunger because the poor are most dependent on natural resources and agriculture to survive. In dry regions, many aquifers are being degraded or depleted because too much water is drawn for agriculture, creating water scarcity. And when desertification damages ecosystems, plants and animals may be at risk of extinction. Biodiversity loss also affects the livelihoods of the poorest people.

Desertification increases the frequency of dust storms. These can carry particulate matter and pathogens or allergens that are harmful to human health. In the Sahara area, the Mideast and South and East Asia, dust storms have contributed to 15 to 50% of all cardiopulmonary deaths. Shifting sands also threaten infrastructure stability and farmland. Moreover, when trees die in dry areas leaving behind large amounts of dry wood for burning, wildfires can become more frequent.

As a result of desertification, land becomes uninhabitable and people must migrate elsewhere to survive. This can engender social and political conflicts in other regions or countries as there will be more competition for resources, especially where resources are already scarce.

Desertification also releases the carbon stored in soils, and because few plants remain to absorb carbon from the atmosphere, desertification contributes to climate change.

Is desertification reversible?

According to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), desertification, land degradation and drought costs the world $878 billion each year. While desertification is considered a permanent state, reversing desertification is possible with extraordinary measures. Restoring 1 billion hectares would reduce poverty and hunger and enhance carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation and water management, which would also help combat climate change.

The Loess Plateau in China is often considered the “paragon of ecological restoration.” For thousands of years, the Loess had been China’s breadbasket, but unsustainable use by humans turned it into a barren wasteland. A combination of government policies and local community participation led to a restoration which involved terracing hillsides, planting trees and grasses, and constructing check dams (small barriers in streams that slow water flow). The initiatives were successful in reversing desertification, reducing erosion, restoring water resources and increasing agricultural productivity. The area has also become a huge carbon sink. However, some critics disapprove of the high-density planting of non-native trees, arguing that non-native trees draw more water than native trees would, and also lessen soil moisture.

Africa’s Great Green Wall program involves 11 countries across the Sahel region that have been affected by desertification for decades. Almost half the land in the Sahel has been degraded due to overpopulation, excessive grazing, deforestation and droughts. Launched in 2007, the program’s original goal was to plant an 8,000 kilometer wall of trees across Africa from Senegal in the west to the eastern Republic of Djibouti, and restore 100 million hectares of land by 2030. So far, about 30 million hectares of land have been restored. The shortfall is attributed to a lack of funding and technical support and poor monitoring. In addition, the project faltered because it failed to predict the best tree species to plant and which trees would have benefited the locals. In some areas of the Sahel, 80% of the trees died as soon as irrigation stopped. One coordinator for the initiative said, “You can plant a tree for $1, but you cannot grow a tree for $1.”

“What they learned was that [the strategy] can’t be imposed from above, but really needs to be sustained by the community,” said Biasutti. “The project has now gone from somebody coming in from the government and planting rows and rows of trees, to having villages being involved in taking care of saplings. And having a multiplicity of purposes so it can be sustained for the long term.” Today, the Green Wall project is described as a mosaic restoration of the land. “There’s a lot more focus on finding ways in which the water that does fall is used, and not lost to run-off or evaporation,” she said. “And the soil matter that has a lot of nutrients is also not lost. It’s about creating local conditions that are appropriate for regenerative stewardship of the soil.” In 2021, the Great Green Wall Accelerator was announced: 134 countries, the World Bank and the UN pledged $14 billion to help complete the Green Wall by 2030.

Another example: The Altiplano, a high plateau in Bolivia, became degraded through overgrazing and poor land management. A restoration effort led by the community used check dams, native grasses and rotational grazing to bring productivity back to the plateau. The efforts also enhanced the livelihoods of locals through sustainable tourism and agricultural products.

Urban areas can also be vulnerable to desertification. Cities around the Sahara must contend with the advancing desert sand and rising temperatures, which can put pressure on water supplies, damage infrastructure and harm human health. Some cities, such as Dakar, Senegal, are employing nature-based strategies to stave off desertification. The Trees in Dry Cities Coalition promotes urban tree planting to help cities fight desertification.

Creating miniforests is another strategy that cities around the world are using to restore their soils, cool temperatures and increase biodiversity. Developed by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki in the 1970s, miniforests can be planted in areas as small as 50 square feet. Soil nutrients are restored, then native vegetation is planted very densely, which causes the plants to grow quickly (10 times as fast as those in tree plantations) as they compete for sunlight. The miniforests sequester carbon, improve groundwater and attract wildlife, insects and fungi.

What solutions help reverse desertification?

These are some lessons that have been learned from previous restoration efforts:

–Nature-based solutions. Planting trees and other vegetation where it doesn’t exist helps to improve soil quality and prevent erosion. But as the Great Green Wall in the Sahel demonstrated, it’s essential to understand the desert microbiome and select the right species to plant. Desert trees such as Acacias and Juniper evergreen, and plant species that have adapted to desert soils with their high salinity and few nutrients, are a more sustainable solution than nonnative trees, which may require millions of dollars in investment and consume much more water to survive. In Nigeria and northern Ethiopia, the use of native trees has made it possible to reclaim desertified land, improve soil quality and restore the ecosystem.

-Water management. Water needs to be conserved and water resources restored through terracing lands, rainwater harvesting, drip irrigation systems, removal of invasive plants and the replanting of native vegetation.

–Sustainable land-management practices and regenerative agriculture. Regenerative agriculture attempts to improve the soil and restore biodiversity as well as help sequester carbon dioxide. It includes strategies such as no-tilling or reduced tilling so that soil is not disturbed; planting cover crops; ensuring crop diversity; using natural fertilizers and pesticides, rotational grazing and agroforestry (i.e., planting trees or shrubs with crops or livestock).

–Local community knowledge. Local people can often offer valuable water management strategies. For example, historically, dryland communities built rock dams or check dams to slow water flow and control erosion; sediment and organic debris caught behind the structures enriched the soil. One traditional method from the Sahel, “half-moons,” are semi-circular depressions made in the ground that slow and capture rainwater runoff. Zai planting pits used in Burkina Faso are holes dug into the ground before seeding so when it rains, nutrients are concentrated where needed and water is retained.

“There’s a lot of room for embracing a system that throws everything at the problem; where you use all the information, you use the fertilizers, you use the tools that we know about, but you also find ways that are very much low-tech and localized to collect water and shade,” said Biasutti.

–Collaboration between stakeholders. Governments, NGOs, private investors and local communities all need to be involved in desertification efforts. Policies, both international and national, such as the Great Green Walls of Africa and China, can promote, fund and incentivize efforts to combat desertification. In addition, policy makers and researchers need to improve aridity monitoring with the latest tools so that early detection of a change in conditions is possible. Local communities must be educated about good land management practices and offered subsidies to adopt them because it’s up to the communities to implement strategies on the ground.

Organizations working to combat desertification

The UN Convention to Combat Desertification’s COP16 summit, which took place in Saudi Arabia last December, was focused on raising global ambitions for land restoration, and spurring action on drought resilience. Unfortunately, the summit ended without an international agreement for tackling droughts. Many other organizations are also working to restore ecosystems and fight desertification. Here are just a few:

The UNEP Generation Restoration project is working with 24 cities around the world on creating blue-green infrastructure to restore urban ecosystems as well as create green belts of native vegetation and trees.

Implemented by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Action Against Desertification is working with 10 African countries to create the Great Green Wall and help them restore degraded land and sustainably manage their drylands.

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Global Drylands initiative works to restore and protect dryland ecosystems through sustainable management policies.

The Nature Conservancy promotes nature-based solutions and regenerative agricultural systems, as well as attempts to mobilize investment for land restoration.

The EcoRestoration Alliance, a group of scientists, environmentalists and grassroots leaders, is focused on the restoration of biodiverse ecosystems to help reduce drought and other climate impacts. Its network supports ecosystem restoration projects around the world by creating collaborations between grassroots and other organizations and indigenous, rural and urban communities.

Source link

Renée Cho news.climate.columbia.edu