3.1. Morphometric Analysis of D. suzukii

The total sample consisted of 572 SWD individuals, comprising 262 males and 310 females, used for the morphometric measurements. Differences in sample sizes between males and females are justified by the species’ sex ratio variation. The morphometric data were analyzed across a temperature range of 21.1 to 28.2 °C. To facilitate more detailed analysis, the data were divided into two temperature categories: ≤24.1 °C and >24.1 °C. This division aimed to balance the number of measurements within each range, with 24.1 °C serving as an approximate midpoint of the entire temperature interval.

The data indicate that females are larger than males, with the thorax being the largest body region (tagma) for both sexes. In the dorsal and lateral views, females have a larger thorax (1013 µm and 1050 µm) compared to males (907 µm and 918 µm). These measurements suggest a more developed thoracic structure in females, but the difference between the two views is not as pronounced, indicating a relatively symmetrical thorax shape, which is important when considering the selection of mesh hole shape.

The abdomen of SWD exhibits clear sexual dimorphism, with females displaying larger dimensions than males in both dorsal and lateral views. In the dorsal view, the female abdomen measures 1001 µm compared to 894 µm for males, while in the lateral view, females measure 766 µm versus 660 µm for males. This suggests that females possess a broader and more developed abdominal structure, potentially linked to their reproductive role. In both sexes, the abdomen is wider than it is deep, indicating a more flattened geometric shape. However, its smaller size compared to the thorax makes this geometric characteristic less significant.

The size differences between males and females are more pronounced in body length than in thorax and abdomen dimensions.

The data also indicate a clear influence of temperature on the body dimensions of SWD, with individuals reared at lower temperatures (21.1–24.1 °C) exhibiting larger body sizes compared to those reared at higher temperatures (24.1–28.2 °C). This trend is consistent across both sexes and all measured traits (body length and thorax and abdomen dimensions). For example, the total body length of males and females is significantly larger in the lower temperature range, with males averaging 2350 µm and females 2804 µm at 21.1–24.1 °C, compared to 2180 µm and 2615 µm at 24.1–28.2 °C. Similarly, the thorax (both dorsal and lateral views) and the abdomen (dorsal view) decrease in size as temperature increases, with larger values recorded at the lower temperature range. However, abdomen height in the lateral view AL is unique in that only females show an increase in size with rising temperatures, while males experience a decrease.

This reduction in size at higher temperatures is more pronounced in males. For instance, male thorax width in the dorsal view decreases from 964 µm to 842 µm between the lower and higher temperature ranges (a 12.7% reduction), while in females, it decreases from 1074 µm to 959 µm (a 10.7% reduction). A similar pattern is observed for thorax lateral measurements and abdomen dimensions.

Temperature and sex also significantly affect thorax width in the dorsal view TD, with both factors showing very low p-values (<0.001). Sex significantly influences thorax width TD, with an F-value of 237.80, while temperature also has a notable effect on this trait, with an F-value of 260.21. Similarly to body length, the interaction between temperature and sex is not significant (p = 0.624), indicating that the influence of temperature on this trait is consistent across males and females.

For the thorax in the lateral view TL, both temperature and sex are significant (p < 0.001), and there is now a significant interaction between temperature and sex (p = 0.003). This suggests that the effect of temperature on thorax size differs between males and females, with one sex being more sensitive to temperature changes than the other. Specifically, temperature has a greater influence on males, who exhibit a pronounced decrease in thorax size under higher temperatures compared to their lower temperature measurements.

Regarding abdomen width in the dorsal view AD, temperature and sex significantly affect this tagma (p < 0.001), with no significant interaction (p = 0.861), suggesting that the size differences between males and females are stable across different temperatures.

In contrast to the other traits, temperature does not have a significant effect on abdomen height in the lateral view AL (p = 0.706), while sex has a strong influence (F = 82.63, p < 0.001). There is a significant interaction between temperature and sex (p < 0.001), indicating that temperature affects males and females differently in this trait. Specifically, male abdomen height decreases slightly from 680 μm at lower temperatures to 638 μm at higher temperatures, while females exhibit an increase from 743 μm to 786 μm. This interaction suggests that the abdomen’s response to temperature changes is more complex in the lateral view, possibly due to sex-specific differences in abdominal development or function.

3.2. Geometrical Characteristics of Protective Nets

The thread thickness (Dhx and Dhy) shows relatively small variation, between 280 and 360 μm, with no clear correlation between thread thickness and hole size. This reflects a rigid design strategy by manufacturers, who do not consider the relationship between thread density and thread thickness to achieve the desired hole sizes while optimizing fabric porosity. Just as with hole sizes, thread thickness impacts the 2D surface area of the holes A2D, which varies significantly from 0.530 to 2.027 mm2. The thickness of the nets tt ranges from 370 to 568 μm, reflecting how tightly packed the weft and warp threads are. This thread tightness plays a crucial role in determining the real (3D) hole opening. However, this is an important parameter that manufacturers do not take into account at all. Additionally, the porosity (φ) ranges from 49.8% to 68.2%, indicating varying levels of air and light transmission. These factors are critical for both crop protection and maintaining adequate environmental conditions for plant growth.

3.3. Efficacy of Protective Nets in Excluding D. suzukii

Nets 6 and 7 (completely effective) have hole widths below 700 μm and hole lengths around 1000 μm, with form factors ψ of 0.699 and 0.600, respectively. Net 9 (also completely effective) has a hole width of 715 μm and a pore length of 742 μm, with a form factor of 0.964. The design of nets 6 and 7 appears to be more suitable, as they provide complete protection against SWD and their porosity is higher than that of net 9, which will undoubtedly improve the crop conditions.

Net 3 has larger hole dimensions (816 × 1333) µm2 compared to net 4 (778 × 1280) µm2. The form factors ψ of both nets are quite similar, 0.608 and 0.612, respectively. However, net 3 (with larger hole size) achieved better efficacy against SWD, which contradicts the logical expectation based on hole size alone. A difference between the two nets lies in the color of the threads: net 3 is made with crystal-colored threads, whereas net 4 has green threads. Therefore, thread color could be a relevant factor to consider in relation to the visual attractiveness of the net to this species.

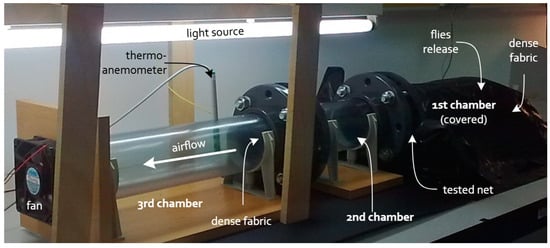

Regarding airflow velocity, the efficacy measurements varied with different airflow velocities (0, 1.5, and 3.0 m/s). For example, in net 3 at ↓T, the efficacy was 100% at 0 m/s but dropped to 86.0% at 3.0 m/s. In the case of net 4, the efficacy decreased significantly when the air velocity increased from 1.5 to 3 m s−1, and this is one of the fabrics with the greatest thickness tt (566 μm). This trend is consistent across most nets, indicating that increased airflow velocity may facilitate the passage of D. suzukii, potentially due to increased pressure or turbulence disrupting the nets’ barrier protection.

The sex ratios of the initial samples compared to those that crossed the nets indicate a trend towards a reduction in the number of females that successfully traversed the exclusion barriers. For example, the initial ratios show that females were consistently more prevalent (e.g., ratios like 1:1.12 and 1:1.24), while the ratios of those that crossed the nets indicate a decline in the proportion of females, such as 1:0.89 and 1:0.82 for nets 7 and 9, respectively. The selective permeability of the nets favors the passage of smaller males, leading to a shift in the sex ratio among those that successfully cross.

We do not find it coherent to conduct an ANOVA with the temperature intervals to support the results of the multiple regression analysis, as the experimental reality is that the temperature varied continuously between 20.4 and 28.7 °C. Therefore, establishing a low and high temperature range serves the purpose of presenting results and understanding the phenomenon but does not align with the true nature of the ANOVA analysis. However, the air velocities u are categorized (0, 1.5, and 3 m s−1), and thus, in this case, the ANOVA analysis is appropriate. The data from this analysis support the results obtained in the multiple regression analysis and highlight the influence of air velocity on efficacy values (F-value = 6.818 and p-value = 0.002).

The greatest impact on efficacy appears to occur when moving from zero velocity (0 m s−1) to a moderate velocity (1.5 m s−1). Beyond this point, further increasing the velocity (up to 3 m s−1) does not lead to significant differences in efficacy, although the general trend observed in the regression model remains negative (efficacy decreases as air velocity increases). As previously mentioned, mesh 4 is an exception to this trend, revealed by the Tukey analysis, as in this case, there is a drastic drop in efficacy when the velocity increases from 1.5 to 3.0 m s−1. Perhaps the combination of hole width (Lpx = 778 μm), length (Lpy = 1280 μm), the shape factor (Lpx/Lpy = 0.608), and net thickness (tt = 566 μm) creates a confluence of factors that leads to this drastic drop in efficacy.

Source link

Antonio J. Álvarez www.mdpi.com